- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Abbreviations

- •1 Is This You or Someone You Love?

- •My Turn

- •This Book

- •All Hearing Losses Are Not the Same

- •The Importance of Hearing in Our Lives

- •The Trouble with Hearing Loss

- •Staying in the Game

- •Just a Bit About Sound

- •What Does the Brain Have to Do with Hearing?

- •The Peripheral Auditory System

- •The Central Auditory System

- •Summary

- •The First Step

- •Audiologists

- •The Goals of a Hearing Evaluation

- •Nonmedical Examination of Your Ears (Otoscopy)

- •Case History Information

- •Test Environment

- •Hearing Evaluation: Behavioral Tests

- •Hearing Evaluation: Physiologic Tests

- •Understanding Your Hearing Loss

- •Describing a Hearing Loss

- •5 What Can Go Wrong: Causes of Hearing Loss and Auditory Disorders in Adults

- •A Quick Review: Conductive, Sensorineural, and Mixed Hearing Loss

- •Origins of Tinnitus

- •Conventional Treatments

- •Alternative Treatments

- •7 Hearing Aids

- •Deciding which Hearing Aids Are Right for You

- •Hearing Aid Styles

- •Special Types of Hearing Aids

- •Hearing Aid Technology (Circuitry)

- •Hearing Aid Features: Digital Signal Processing

- •Hearing Aid Features: Compatibility with Assistive Listening Technologies

- •Hearing Aid Features: Listener Convenience and Comfort

- •Hearing Aid Batteries

- •Buying Hearing Aids

- •The Secret of Success

- •How a Cochlear Implant Works

- •Cochlear Implant Candidacy

- •Expected Outcomes for Cochlear Implant Users

- •Cochlear Implant Surgery

- •Device Activation and Programming

- •Choosing Among Cochlear Implant Devices

- •Auditory Brainstem Implants

- •Current and Future Trends

- •9 Hearing Assistance Technology

- •Hearing Assistance Technology

- •Telephones and Telephone Accessories

- •Auxiliary Aids and Services

- •Alerting Devices

- •Hearing Service Dogs

- •Hearing Rehabilitation

- •Hearing Rehabilitation Services

- •Hearing Rehabilitation Services Directly Related to Hearing Aids

- •Hearing Rehabilitation Services beyond Hearing Aids

- •Support/Advocacy Groups

- •The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

- •Summary: Good Communication Habits

- •11 Prevention of Hearing Loss

- •Preventable Causes of Hearing Loss

- •Hearing Loss Caused by Noise Exposure

- •Hearing Loss Resulting from Ototoxicity

- •APPENDICES

- •Notes

- •Resources

- •Index

How We Hear |

37 |

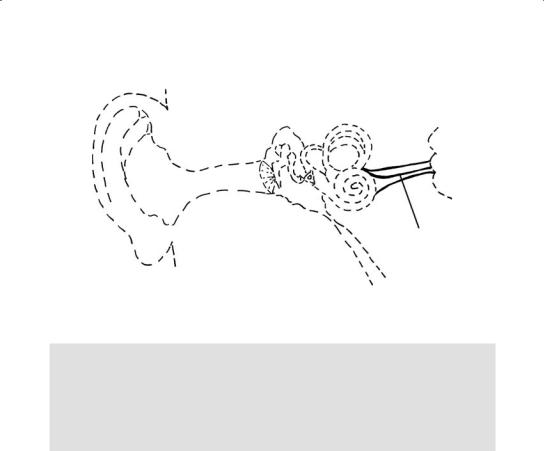

CN VIII

Figure 3.8. Cranial Nerve (CN) VIII.

My Dad

The hearing losses in my dad’s right and left ears were caused by different conditions (both of which are discussed in Chapter 5); however, both conditions originate in the cochlea. The cochlea is the most common site of damage among people who lose their hearing as adults.

Cranial Nerve VIII

Auditory nerve receptors are located just beneath the hair cells in the cochlea. These receptors send impulses through fibers that join together to make the auditory branch of CN VIII. The auditory branch joins the vestibular branch, and CN VIII travels through a bony canal toward the brainstem—all hearing information enters the brain through this thick band of nerve fibers. CN VIII joins the brainstem at the point where several parts of the brain come together to form the cerebellopontine angle (CPA). It’s in the bony canal and the CPA that acoustic tumors are most likely to develop (see Chapter 5).

THE CENTRAL AUDITORY SYSTEM

Once in the brainstem, auditory information (now in the form of a neural code) is analyzed and modified at various processing stations (called nuclei) before being sent “upstream” to other stations for further analysis and modification. As an example, information coming from the two ears is analyzed and compared at various stations; the comparisons help us to locate the source of sounds and to suppress background noise in the presence of multiple conversations (we’re meant to hear with two ears;

38 |

The Praeger Guide to Hearing and Hearing Loss |

that’s why two hearing aids are usually better than one). The brain is able to synthesize and interpret the coded information contained within many neurons, resulting in the perception of sound.

There are many alternative and overlapping pathways within the central auditory system. Ultimately, they all lead to specialized auditory areas located in the temporal lobes of the brain (just above the ears). Because there’s so much duplication, damage to the central auditory pathways does not always result in a hearing loss, at least in the conventional sense. Instead, central auditory disorders tend to be more subtle (for example, an inability to locate the source of sounds) and may not be revealed without special auditory tests.

SUMMARY

The powers of the human auditory system are nothing short of awesome. The human ear is capable of perceiving an enormous range of frequencies and intensities. The highest sound that can be heard is a thousand times higher (in frequency) than the lowest. The range of intensities that the ear can handle is even greater. The human ear can tolerate a sound 10 million times greater than the softest sound it can detect. This staggering range accounts for the use of a logarithmic scale (decibels or dB) to express intensity—the numbers would be too large to manage using a linear scale (like a ruler). Remarkably, in addition to being sensitive to a vast range of sounds, the human ear can detect minute differences in frequency, intensity, and time. It’s this sensitivity to tiny differences between sounds that enables us to understand speech.

Our ears process extremely complex sounds in real time, around the clock, and often under extremely poor conditions. Sound waves traveling through air are collected by the pinna and funneled to the eardrum by way of the ear canal. The eardrum faithfully reproduces the sound waves that hit it, setting the ossicular chain into motion. The mechanical movement of the ossicular chain sets the fluids of the cochlea into motion, causing hair cells to be stimulated. This stimulation triggers neural impulses that are sent by means of the CN VIII to auditory stations in the brainstem. In the brainstem, networks of neurons act on the auditory information and send signals to specialized auditory locations in the brain. Approximately 30,000 nerve fibers coming from the inner ear communicate with about 100,000 neurons in the brainstem, and tens of millions of neurons in the auditory cortex. Neural information from the auditory system is combined with neural information from other sensory systems and neural information stored from past experiences to produce a meaningful interpretation of sound—all in an instant. In other words, it takes only an instant for the auditory system to transform molecular disturbances traveling through air into the words, “I love you.”

CHAPTER 4

Assessment of Hearing: Understanding

the Results of Your Hearing Test

Knowledge. . .is power.

Francis Bacon

This chapter is important because it discusses the ways in which hearing losses are characterized. In particular, reading the sections toward the end of the chapter (beginning with “Understanding Your Hearing Loss”) will help you to learn about the nature of hearing loss—a necessary step if you hope to minimize its negative impact.

The tests and procedures described throughout this book are considered “best practices.” Although not every test described in this chapter is required in every hearing assessment, sometimes practices proven to be helpful are ignored. One example from this chapter would be testing speech perception in background noise. Other examples will become apparent when hearing rehabilitation is discussed in Chapter 10. Nonetheless, knowledge is power. Because better-informed consumers insist on better products and services in the marketplace, educating readers about what they should expect is an important goal of this book.

Like some of the other chapters to come, this one assumes some knowledge about the anatomy and physiology of hearing. (If you haven’t done so already, you may want to read Chapter 3.) In this chapter, if a paragraph or section seems too technical, skip it and keep reading. You needn’t understand everything to benefit from material that comes later in the chapter.

40 |

The Praeger Guide to Hearing and Hearing Loss |

THE FIRST STEP

If you suspect that you may have a hearing loss, the first step is to arrange for a thorough evaluation by a professional—but whom should you see first—a physician or an audiologist?

Physicians treat medical conditions affecting the ear: infections, diseases, tumors, and other problems. However, only 5 to 10 percent of the hearing problems that affect adults are medically or surgically treatable. In contrast, audiologists are hearing specialists trained in the prevention, diagnosis, and nonmedical treatment of hearing (and balance) disorders. Their job is to define the nature of a hearing loss and provide appropriate nonmedical treatment in the form of hearing technology (for example, hearing aids, cochlear implants, and assistive listening devices), counseling, and therapy. In other words, audiologists are trained to help people maximize the hearing that they have left (this is called residual hearing) and cope with hearing loss. Audiologists see patients with or without a physician’s referral; however, they’re quick to refer patients to physicians when hearing (or balance) problems suggest the need for medical evaluation. (Note: As of June 2008, Medicare beneficiaries currently need a physician’s referral to see an audiologist; however, bipartisan legislation before the U.S. Congress would eliminate that requirement, giving them “direct access” to audiologists.)

Criteria for Medical Referral1

In accordance with guidelines issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1977, your audiologist will refer you to a physician if you have any of the following conditions. (Unfamiliar terms are explained later in the chapter.)

A visible deformity of the ear

Active drainage or a history of drainage from the ear during the previous 90 days

Sudden or rapidly progressive hearing loss within the previous 90 days

Acute or chronic dizziness

Unilateral or asymmetric hearing loss within the previous 90 days

Untreated conductive hearing loss (as evidenced by an air–bone gap of 15 dB or greater at 500, 1,000, and 2,000 Hz on the audiogram)

Earwax or foreign body blocking the ear canal

Pain or discomfort in or around the ear

In addition, your audiologist will make a medical referral if you have

Growths in the ear canal

Lesions (sores) in the ear canal

Unusual redness of the ear canal or eardrum