Учебники / Operative Techniques in Laryngology Rosen 2008

.pdf

|

Chapter 35 |

225 |

a characteristic prephonatory burst of EMG activity for optimal injection localization.

c)Posterior cricoarytenoid muscle localization and injection for Abductor SD

i.Retrolaryngeal approach

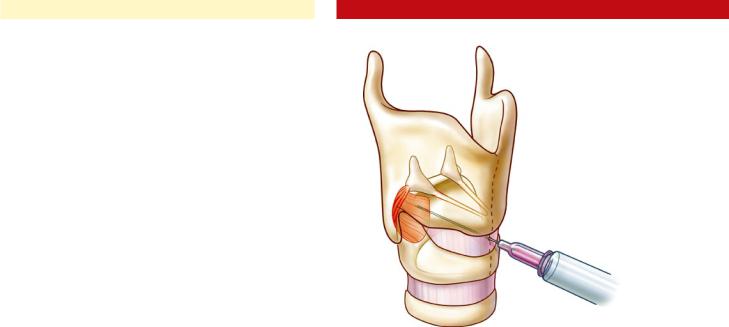

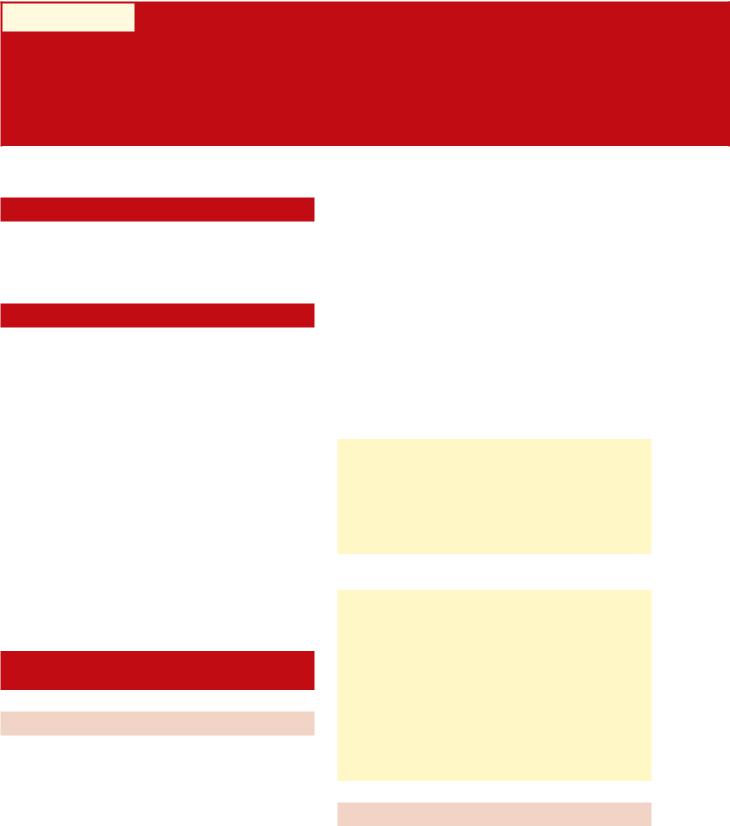

The patient is seated upright, and the injector places his or her thumb at the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage on the side to be injected. Using counterpressure on the opposite side of the thyroid cartilage from the other four fingers, the larynx is gently rotated to expose its posterior aspect. The needle pierces the skin along the lower half of the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage and is advanced until it stops against the posterolateral surface of the cricoid. The needle is then pulled back slightly, and the patient is asked to sniff to confirm placement (Fig. 35.3). When this produces brisk recruitment, the toxin is injected.

ii.Translaryngeal approach

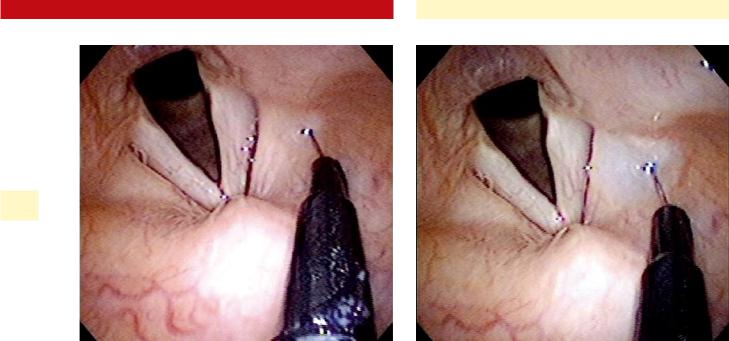

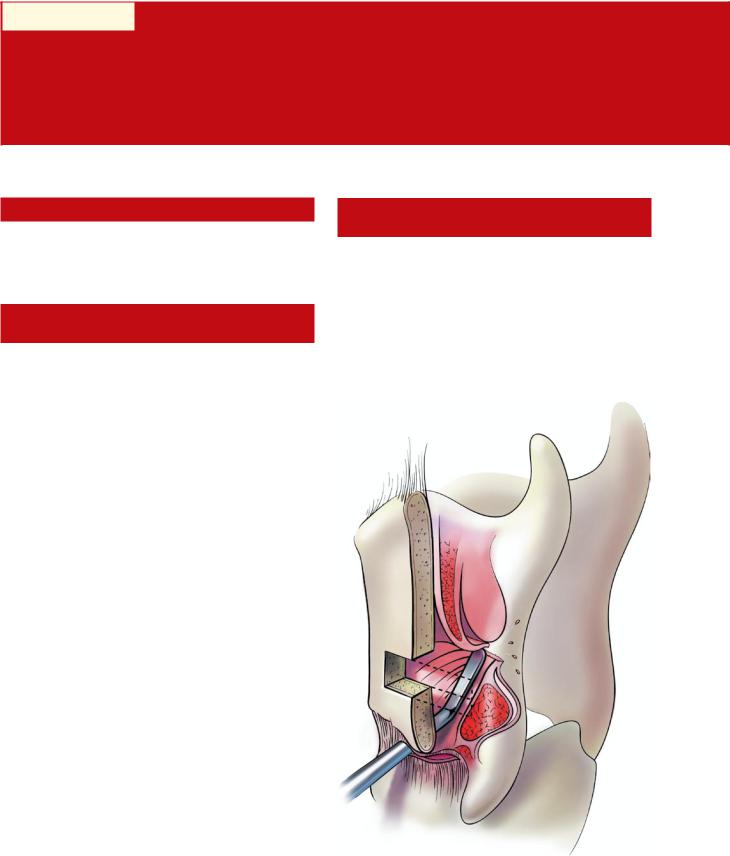

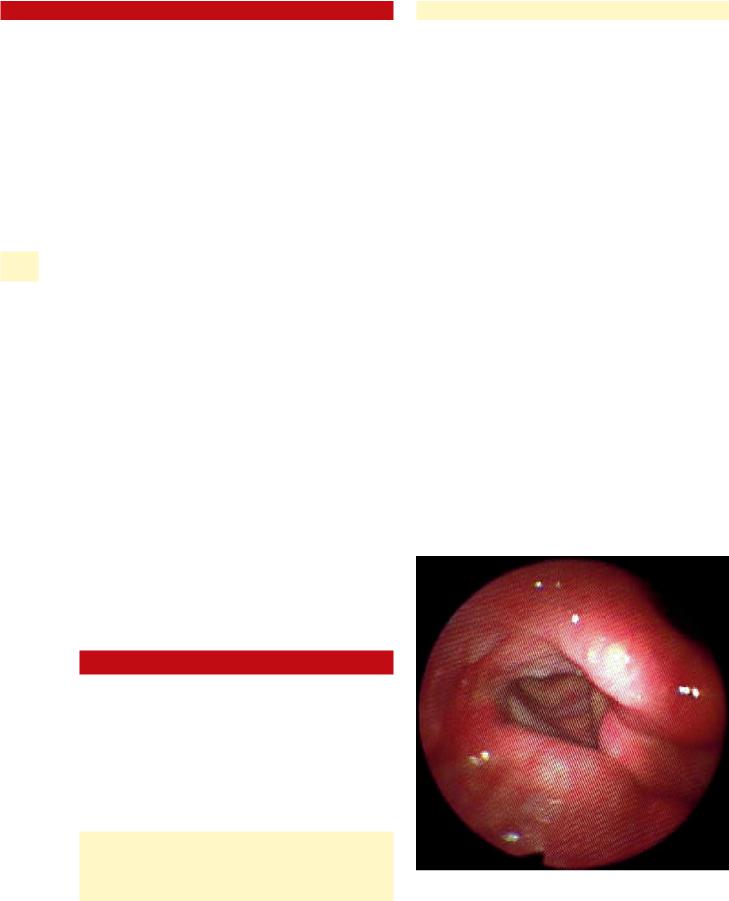

In this approach, the needle must cross the endolar yngeal mucosa so an intratracheal injection of 4% plain lidocaine is useful to prevent coughing and discomfort. The needle is inserted through the cricothyroid membrane in the midline, and directed posteriorly across the lumen of the glottis (identified by the characteristic airway buzz on EMG) angled toward the side to be injected. Using gentle pressure, it is pushed through the lamina of the cricoid cartilage until the opposite side is reached (due to cricoid cartilage calcification, this approach may not be possible in the older patient). The first electrical signal encountered on the far side represents posterior cricoarytenoid muscle. Placement is confirmed by muscle activation during sniffing, and the toxin is injected (Fig. 35.4). It is often useful (especially when learning the technique) to employ an assistant to provide flexible laryngoscopy visualization on a monitor during PCA injections (see Chap. 33, “Peroral Vocal Fold Augmentation in the Clinic Setting”). The surgeon should be aware that fragments of cartilage might plug the needle lumen as it crosses the cricoid, and expelling them to permit injection may require considerable force on the plunger of the syringe; a luer-lock syringe will prevent toxin leakage around the needle hub.

d)Botulinum toxin injection with laryngoscopic guidance for Adductor SD

i.Local anesthesia is obtained by performing a puncture through the cricothyroid membrane, and instilling approximately 3 ml of 4% lidocaine into the airway.

ii.The nasal cavity is anesthetized and a flexible laryngoscope, attached to videomonitor, is inserted through the nasal cavity and advanced to a level slightly above the vocal folds. An assistant maintains the scope in position in order to provide constant visual feedback during the procedure.

Alternatively, the surgeon may use a rigid telescope for laryngeal visualization (nondominant hand) while

Fig. 35.4 Placement of EMG needle into the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle, using a translaryngeal approach

manipulating the needle with the other. The patient (or an assistant) must stabilize the tongue to facilitate good transoral visualization.

iii.A 1-ml syringe filled with botulinum toxin is attached to a 27-g needle. The needle is placed through the cricothyroid membrane near the midline, using videomonitoring to confirm the location of the needle tip in the subglottic airway.

iv.The needle is angled toward the posterior aspect of the vocal fold, piercing the infraglottic mucosa, and advancing the needle laterally into the adductor musculature of the vocal fold (TA-LCA complex) (Fig. 35.2). The posterior third of the membranous vocal fold is the targeted region for Botox placement. A similar injection is then performed on the opposite vocal fold through the same approach via the cricothyroid membrane. Visual confirmation, via the flexible laryngoscopic monitoring is used to confirm correct placement and to insure that inadvertent “loss” of the Botox does not occur.

e)Supraglottic botulinum toxin injection with laryngoscopic guidance for Adductor SD.

Supraglottic botulinum toxin injection with laryngoscopic guidance is effective for treatment of adductor spasmodic dysphonia as well as essential tremor involving the supraglottis. Two different injection approaches can be used to perform supraglottic botulinum toxin injection, (1) peroral approach or (2) an approach using a working channel of a flexible laryngoscope. Each of these two approaches are equally efficacious, and the decision to use one approach or the other is usually determined by the availability of the equipment to the surgeon. From a patient-comfort perspective, the injection through the working channel of a flexible laryngoscope is better tolerated.

226 |

Botulinum Toxin Injection of the Larynx |

|

35

Fig. 35.5 False vocal fold site(s) for trans-oral botulinum toxin injection

1.Topical anesthesia nasal/oropharynx

a)Topical oxymetazoline/Pontocaine 2% spray to nasal cavities

b)Topical Cetacaine spray to oral cavity (palate/posterior pharynx)

2.Videomonitoring/topical anesthesia of larynx

a)A video camera is attached to a flexible laryngoscope or a distal chip flexible laryngoscope, inserted through the nasal cavity (typically the left side) by an assistant, employing a “videocart system.” The scope is generally maintained slightly below the palate so that the tongue base and larynx can be easily viewed on the video monitor.

b)Four percent lidocaine drip onto larynx under flexible guidance (3–5 ml; see Chap. 33)

The patient is bent forward at the waist with the neck extended in a “sniffing” position to maximize laryngeal exposure. The tongue is grasped with a 4 × 4 gauze with the surgeon’s left hand. A 3-ml syringe of 4% lidocaine (40 mg/ml) attached to an Abraham cannula (Pilling, Fort Washington, Pa.) is advanced into the oropharynx. Approximately 1 ml is deposited over the tongue base, and 2–4 ml is dripped onto the vocal folds during phonation, producing the characteristic “laryngeal gargle”. The maximal recommended dose of 4% lidocaine is approximately 7–8 ml (4.5 mg/kg; approximately 300 mg for a 70-kg patient).

3.Peroral passage of the needle into the endolaryngeal region

a)The Botox is drawn up in a 1-ml syringe, and secured into the orotracheal injector device (Medtronic ENT, Jacksonville, FL) with the

Fig. 35.6 Characteristic submucosal bleb immediately after transoral botulinum toxin injection

curved needle. Disposable 27-g needles are used with this system.

b)The needle is advanced into the oropharynx under direct visualization. The patient is instructed to phonate /a/ as the needle enters the oral cavity, which results in palatal raising, clearing the path into the oropharynx. The assistant should position the flexible scope just above the palate until the needle is visualized in the oropharynx.

c)The injector is then advanced, and the needle tip is then guided into the hypopharynx, under endoscopic visualization, as the assistant follows closely behind with the flexible scope The assistant must be adept at manipulating the scope; consistent visualization of the injector can be challenging in a narrow airway with copious secretions. The flexible scope should be positioned a few millimeters above the false vocal folds providing a clear, well-illuminated, magnified view of the false vocal folds.

4.Laryngeal injection of Botox

a)The needle is guided into the posterolateral and/ or mid-lateral false vocal fold under laryngoscopic visualization (Fig. 35.5).

b)Botox is injected into a superficial (submucosal) plane, forming a characteristic bleb (Fig. 35.6).

c)Five to 7.5 U are typically deposited in both false vocal folds (total of 10–15 U).

An alternative way to perform supraglottic botulinum toxin injection with laryngoscopic guidance is to use a flexible laryngoscope with a working channel, or a flexible laryngoscope with an endosheath working channel apparatus. After adequate anesthesia to the larynx has been achieved

via the approach described above, a fine-gauge injection needle can be passed through the working channel of the flexible laryngoscope (NM-9L-1, Olympus America, Center Valley, Pa.) and the supraglottic larynx can be injected with botulinum toxin as discussed above.

35.6Postprocedure Care and Complications

Patients may be discharged immediately after the injection. Patients receiving TA-LCA injections should be cautioned regarding an initial period of (1) breathiness and (2) dysphagia, especially to liquids, as discussed above. Patient receiving their second posterior cricoarytenoid injection should be advised regarding dyspnea and stridor.

Patients that received laryngeal anesthesia should be advised to retrain from any peroral intake for 2 hours (or until sensation returns to the larynx/pharynx) to avoid the risk of aspiration.

Key Points

■Percutaneous, EMG-guided botulinum toxin injection

■Effective administration of botulinum toxin depends on

■Accuracy of injection

■Minimizing diffusion to neighboring muscles

■Appropriate dosing

■When using EMG, confirmation of needle placement by muscle activation during appropriate activity (e. g., sustained “ee” or Valsalva for the thyroarytenoid, sniffing for the posterior cricoarytenoid) is essential to accuracy.

■Diffusion is minimized by injecting a small volume of solution, ideally 0.1 ml.

■Approximate dosing is determined by muscle mass and experience treating a given muscle. Precise dosing for each patient is determined by careful assessment of clinical result and adjustment of subsequent treatment.

■Percutaneous injection of botulinum toxin with laryngoscopic guidance

■Percutaneous injection of Botox under flexible (or rigid) laryngoscopic guidance is an ideal technique for the practitioner who performs

Chapter 35 |

227 |

laryngeal injections infrequently because it is easier to master and relies on visual confirmation of the target, rather than blind needle placement. However, it does require an assistant to hold the flexible laryngoscope.

■The response to botulinum toxin is similar with this technique when compared to EMG guided technique, except:

■Higher doses are required

■Delayed onset of action (up to 5 days) occurs

■Toxin effect that is less consistent

■Supraglottic botulinum toxin injection with flexible laryngoscope guidance

■Supraglottic peroral Botox injection with flexible laryngoscopic guidance is indicated in selected patients with adductor spasmodic dysphonia (especially professional voice users and supraglottic-based essential tremor).

■Advantages of supraglottic botulinum toxin (over EMG-guided approach) for spasmodic dysphonia

■Smoothing of the vocal “peaks and troughs” associated with serial EMG-guided Botox injections

■Less severe (minimal-to-no) breathy voice after injection

■Disadvantages of supraglottic botulinum toxin for spasmodic dysphonia

■Shorter duration of effect (6–8 weeks)

■Variable patient response (variable supraglottic muscular anatomy)

Selected Bibliography

1Aoki KR (2004) Pharmacology of botulinum neurotoxins. Oper Techniques Otolaryngol 15:81–85

2Blitzer A, Brin MF, Stewart CF (1998) Botulinum toxin management of spasmodic dysphonia (laryngeal dystonia): a 12-year experience in more than 900 patients. Laryngoscope 108:1435–1441

3Blitzer A, Sulica L (2001) Botulinum toxin: basic science and clinical uses in otolaryngology. Laryngoscope 111:218–226

4Bové M, Daamen N, Rosen C et al (2006) Development and validation of the vocal tremor scoring system. Laryngoscope 116:1662–1668

5Simpson CB, Amin MR (2004) Office-based procedures for the voice. Ear Nose Throat J 83(Suppl.):6–9

6Sulica L, Blitzer A (2004) Botulinum toxin treatment of spasmodic dysphonia. Oper Tech Otolaryngol 15:76–80

Part C Laryngeal Framework

Surgery

Chapter 36 |

|

Principles of Laryngeal |

36 |

Framework Surgery |

36.1Fundamental and Related Chapters

Please see Chaps. 1, 5, 8, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, and 42 for further information.

36.2Introduction

The general goal of laryngeal framework surgery is to improve phonatory glottal closure by altering vocal fold position. Medialization laryngoplasty, also called type I thyroplasty, is the most commonly performed laryngeal framework surgery, typically used to correct glottic insufficiency from a variety of causes, but most often from unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Whereas injection augmentation techniques principally improve glottal closure by expansion of the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle, laryngoplasty techniques employ implant material in the paraglottic space to displace the affected vocal fold(s) medially into a more favorable phonatory position. These materials include Silastic, hydroxylapatite, polytetrafluoroethylene ribbon (GORE-TEX®) and titanium. Medialization laryngoplasty may be used in conjunction with an arytenoid repositioning procedure, an adjunctive technique that can be used to alter vocal fold height and tension by manipulating the arytenoid along its physiologic axis of rotation (see also Chaps. 40, “Arytenoid Adduction” and 41, “Cricothyroid Subluxation”).

36.3Surgical Indications and Contraindications

36.3.1 Medialization Laryngoplasty

The primary indication for medialization laryngoplasty (ML) is symptomatic glottic insufficiency. The goals of the surgery are to improve voice quality and protect the airway by achieving improved glottic closure during phonation and swallowing.

Nevertheless, it is important to understand that vocal fold medialization does not always provide a sure remedy. In the presence of other motor or sensory deficits, as in a high vagal nerve lesion, the ability to close the glottis does not necessarily mean that this will occur appropriately during deglutition. Medialization is indeed likely to help, but many patients continue to have medically significant aspiration. Due caution is war-

ranted in making feeding recommendations after medialization in such individuals. A complete reevaluation of swallowing function is prudent after medialization in such patients.

Medialization laryngoplasty has been advocated by some as a treatment for glottic insufficiency due to soft tissue loss in the aspect of the superficial vocal fold, such as is found in postsurgical scarring or sulcus vocalis. However, it is not well suited for these conditions, as it in no way addresses the lack of tissue pliability and may not yield significant voice improvement. It is worth noting that there is considerable evidence to suggest that at least part of the so-called “bowing” that has been accepted as the clinical correlate of vocal fold aging may also be due to changes in the lamina propria and loss of vocal fold muscle bulk, and thus medialization may represent only a partial solution.

Indications for ML include:

■Symptomatic glottic insufficiency (dysphonia and/or aspiration), especially if there is little chance of return of normal neurologic function

Glottic insufficiency can be due to:

■Unilateral vocal fold paralysis

■Unilateral or bilateral vocal fold paresis

■Vocal fold atrophy, including age-related atrophy

Contraindications include:

■Previous history of radiation therapy to the larynx (relative)

■Malignant disease overlying the laryngotracheal complex

■Poor abduction of the contralateral vocal fold (due to airway concerns)

■Because medialization inevitably leads to some narrowing of the airway, patients with moderate- to-severe bilateral vocal fold paresis may not be candidates for medialization. At least one vocal fold should have intact inspiratory vocal fold abduction for a medialization procedure to be considered

36.3.2 Arytenoid Adduction

Arytenoid adduction and arytenopexy as described by Zeitels is an important adjunct in selected cases of vocal fold paralysis. The physiologic effects of arytenoid adduction are not completely understood, and some debate continues. However, there is consensus concerning the following basic premises.

232 |

Principles of Laryngeal Framework Surgery |

Arytenoid adduction/re-position:

■Rotates the arytenoid cartilage

■Medializes and stabilizes the vocal process

■Lowers the position of the vocal process

■Lengthens the foreshorted vocal fold

In patients with vocal fold paralysis who have a lack of vocal process contact during phonation (large posterior gap) and those with vocal folds at different levels, arytenoid adduction should be considered in addition to medialization laryngoplasty. Videostroboscopy often provides valuable informa-

36 tion about vocal process contact and vocal fold height, and therefore is useful preoperatively in assessing which patients may need an arytenoid adduction. A maximum phonation time of < 5 seconds has also been identified as a predictor of the need for arytenoid adduction in cases of vocal fold paralysis.

36.3.3 Cricothyroid Subluxation

Cricothyroid subluxation was developed by Steve Zeitels to address the problems of a shortened vocal fold frequently seen in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The concept of the procedure is to lengthen the vocal fold by increasing the distance from the cricoarytenoid joint (cricoid) to the anterior commissure (thyroid cartilage) by subluxing the cricothyroid joint on the side of the unilateral vocal fold paralysis. This results in a rotation of the anterior commissure away from the midline in a direction contralateral to the side of the unilateral vocal fold paralysis.

Cricothyroid subluxation is an adjunct procedure to medialization laryngoplasty. This can be done with arytenoid adduction also, but is typically only used with medialization laryngoplasty. Cricothyroid subluxation addresses the commonly seen problem of a shortened vocal fold associated with unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The only other procedure that can lengthen a paralyzed vocal fold is arytenoid adduction (see Chap. 40, “Arytenoid Adduction”).

36.4Patient Selection for Laryngeal Framework Surgery

Although any patient with symptomatic glottic insufficiency is technically a candidate for framework surgery, medialization laryngoplasty is not necessarily the best approach in every case. The ideal candidate for medialization laryngoplasty is a patient with moderate to severe glottic insufficiency (2–3 mm or greater glottic gap on phonation) manifested by weak, breathy dysphonia and/or dysphagia. Conversely, most patients with minor degrees of glottic insufficiency (<1-mm glottic gap on phonation) who have minimal voice symptoms (e. g., vocal fatigue) may be better suited for voice therapy and/or injection augmentation (see Chaps. 5, “Glottic Insufficiency: Vocal Fold Paralysis, Paresis, and Atrophy”; 31, “Vocal Fold Augmenta-

tion via Direct Microlaryngoscopy”; 33, “Peroral Vocal Fold Augmentation in the Clinic Setting”; and 34, “Percutaneous Vocal Fold Augmentation in the Clinic Setting”).

Because medialization laryngoplasty is performed under local anesthesia, anxious/uncooperative patients, and pediatric patients are not ideally suited for this technique.

36.5Timing of Medialization Laryngoplasty

If the status of the nerve injury is unknown or LEMG data are equivocal or favorable for spontaneous recovery, then medialization surgery is best delayed until 6–12 months after nerve injury to allow for spontaneous recovery. The patient with troublesome symptoms may be treated by any of a number of temporary measures in the meantime principally injection augmentation (see Chaps. 31, “Vocal Fold Augmentation via Direct Microlaryngoscopy”; 33, “Peroral Vocal Fold Augmentation in the Clinic Setting”; and 34, “Percutaneous Vocal Fold Augmentation in the Clinic Setting”).

Most surgeons advocate waiting at least 3 months after a known vagal or recurrent nerve transection before performing medialization laryngoplasty. Early or “primary” medialization (performed within the first 3 months after nerve injury) has fallen into disfavor, due to progressive atrophy of the vocal fold from ongoing nerve degeneration, which results in a return of glottal insufficiency weeks to months after medialization.

In select cases, medialization between 3 and 9 months can be considered, especially if electromyography shows severe neuronal degeneration without evidence of neural recovery or the history strongly suggests nerve transection. In these cases, the patient should be counseled that the implant might need to be removed if vocal fold function returns. It is worth noting that in the very rare cases of recovery of vocal fold motion after laryngoplasty that have been observed, the implant does not appear to interfere with function, and has rarely required removal.

36.6Technical Notes and Pertinent Anatomic Landmarks for Medialization Laryngoplasty

Although many techniques and implant materials for medialization laryngoplasty exist, certain general principles of laryngeal anatomy can be universally applied. The level of the vocal fold lies closer to the lower border of the thyroid cartilage lamina than to the upper, and not at its midpoint, as is frequently (and erroneously) stated. It is important to place the thyroplasty window at the most inferior location possible. This will usually encompass the level of the vocal fold and make successful medialization possible with appropriate implant positioning. The inferior limit of placement is determined by the integrity of the cartilaginous strut below the window, which should be at least 3 mm high to prevent fracture, which destabilizes the implant in a way that usually prevents effective medialization. As

|

Chapter 36 |

233 |

a result of this limit, the implant often needs to be carved such that medialization occurs at the inferior limit of the window to avoid ventricular mucosa/false cord displacement.

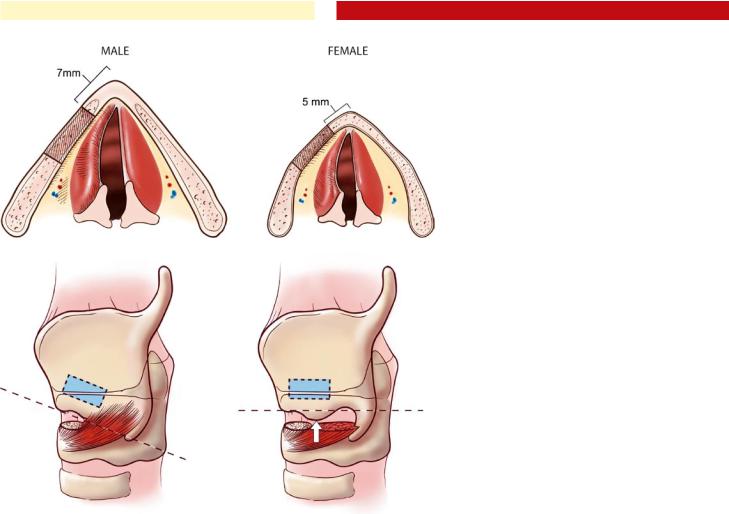

Another important anatomic consideration is the genderrelated differences in the configuration of the thyroid cartilage. In males, the vocal folds are longer, and the thyroid ala form a more acute angle when compared with the female larynx These anatomic differences require a more posterior location of the cartilaginous window in the male larynx to avoid excessive or disproportionate displacement of the anterior third of the vocal fold, which will result in strained or “pressed” voice. In general, the leading edge of the window is placed 7 mm back from the midline of the thyroid cartilage in males and 5 mm in females (Fig. 36.1). Many implants are shaped to medialize tissue in a plane exactly parallel to the long axis of the thyroplasty window; its orientation is thus an important factor for surgical success. The inferior border of the thyroid lamina is the most reliable guide to determining the plane of the long axis of the vocal fold. To accurately identify this plane, the inferior tubercle should be completely exposed and excluded from the determination of the plane along the long axis of the vocal fold (Fig. 36.2).

Preserving some flexibility in medialization laryngoplasty technique to allow for individual variations in laryngeal anatomy is necessary to achieve consistently satisfactory surgical results. Being able to check on the result of medialization in-

Fig. 36.1 Gender differences in medialization laryngoplasty. The more oblique angulation of the thyroid cartilage in females, along with the shorter length of the vocal folds requires that the medialization window be placed more anteriorly (5 mm in females, 7 mm in males)

Fig. 36.2 Diagram showing the incorrect (left) and correct (right) method of exposing the inferior thyroid ala. On the left, the cricothyroid fibers have not been divided from the inferior border, and an incorrect, downwardly sloping line is used to trace the proposed horizontal plane of the vocal fold. On the right, a thorough dissection of the inferior thyroid ala allows the true horizontal plane of the vocal fold to be outlined, ensuring correct window placement. In this case, the inferior muscular tubercle (arrow) is ignored when determining the plane

traoperatively by means of flexible laryngoscopy, and auditory perceptual evaluation is essential to understanding the reason for a poor phonatory result in time to correct it, therefore, a flexible laryngoscope, its light source, a camera, and a monitor should be used for every case.

Conflicting advice regarding the inner perichondrium has appeared in the literature. Maintaining the perichondrium intact effectively prevents medial migration and extrusion of the implant, and minimizes the possibility of endolaryngeal bleeding. Isshiki continues to advise its preservation in combination with Silastic and a cartilage island, as do McCullough and Hoffman when using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene ribbon. However, the medial projection of many preformed implants makes their insertion impossible unless the internal perichondrium is opened. In addition, an intact perichondrium tends to distribute the vector of medialization throughout the window, leading to less precise medialization.

It is important to conceptualize medialization of the vocal fold in three dimensions. The most obvious dimension is medial/lateral, because the amount of medial displacement must be precisely determined to close the glottic gap. Just as important, however, is the anterior–posterior dimension. Anterior displacement must be avoided, while a well-defined “sweet spot” at the posterior aspect of the vocal fold is key to optimizing results. The superior–inferior dimension is often the least discussed, but no less important. This dimension is also

234 |

Principles of Laryngeal Framework Surgery |

|

|

|

the most difficult to judge intraoperatively. A minor error in |

|

|

medialization within the superior–inferior plane can result in |

|

|

height mismatch during vocal fold closure. This mismatch is |

|

|

difficult to detect during intraoperative flexible laryngoscopy, |

|

|

and may only later be discovered with videostroboscopy post |

|

|

operatively. |

|

|

Details of technique specific to various implant materials |

|

|

and steps and modifications required to perform arytenoid |

|

|

repositioning surgery in conjunction with medialization la- |

|

|

ryngoplasty are covered elsewhere (see Chaps. 38, “Silastic |

|

|

Medialization Laryngoplasty for Unilateral Vocal Fold Paraly- |

|

|

sis”; 39, “GORE-TEX® Medialization Laryngoplasty”; and 40, |

36 |

|

“Arytenoid Adduction”) |

|

|

|

Key Points

■Medialization laryngoplasty and arytenoid adduction are the primary laryngeal framework techniques used to correct glottic insufficiency

■The indications for laryngeal framework surgery include:

■Unilateral vocal fold paralysis

■Bilateral vocal fold atrophy/paresis

■The ideal candidate for medialization laryngoplasty is a patient with moderate to severe glottic insufficiency (2- to 3-mm or greater glottic gap on phonation) manifested by weak, breathy dysphonia and/or dysphagia. Conversely, most patients with minor degrees of glottic insufficiency (<1-mm glottic gap on phonation) who have minimal voice symptoms (e. g., vocal fatigue) may be better suited for injection augmentation and/or voice therapy.

■Medialization laryngoplasty can be performed with a variety of implant substances, including Silastic, GORE-TEX, Hydroxylapatite, and Titanium.

■In unilateral vocal fold paralysis (UVFP), framework surgery is generally performed after a waiting period of 6–12 months to allow for spontaneous recovery.

■Early medialization can be considered in select cases including: complete nerve transec-

tion, severe neuronal degeneration as seen with laryngeal electromyography, or in a clinical setting where there is little chance for recovery of vocal fold mobility (e. g., UVFP due to a malignancy). In these cases, a delay of 3 months from the time of injury is recommended to allow vocal fold atrophy to occur. Temporary vocal fold injection can be used acutely in these patients prior to proceeding with laryngeal framework surgery

■The level of the vocal fold lies closer to the lower border of the thyroid cartilage lamina, and not at its midpoint. The thyroplasty window should be placed as inferior as possible.

■Gender-related difference in the thyroid lamina requires a more posterior location for the medialization window in males.

■The inner perichondrium of the thyroid lamina should be incised to gain access to the paraglottic space during medialization. An intact inner perichondrium limits the depth and precision of vocal fold displacement.

Selected Bibliography

1Cohen JT, Bates DD, Postma GN (2004) Revision Gore-Tex medialization laryngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:236–240

2Isshiki N, Morita H, Okamura H, Hiramoto M (1974) Thyroplasty as a new phonosurgical technique. Acta Otolaryngol 78:451–457

3Netterville JL, Stone RE, Luken ES, Civantos FJ, Ossoff RH (1993) Silastic medialization and arytenoid adduction: the Vanderbilt experience. A review of 116 phonosurgical procedures. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 102:413–424

4Netterville JL, Billante CR (2004) The immobile vocal fold. In: Ossoff RH, Shapshay SM, Woodson GE, Netterville JL (eds) The larynx. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 269–305.

5Rosen CA (1998) Complications of phonosurgery: results of a national survey. Laryngoscope 108:1697–1703

6Woo P. Arytenoid adduction and medialization laryngoplasty (2000) Otolaryngol Clin N Am 33:817–839

7Woodson GE, Picerno R, Yeung D et al (2000) Arytenoid adduction: controlling vertical position. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 109:360–364

Chapter 37 |

|

Perioperative Care for Laryngeal |

37 |

Framework Surgery |

37.1Fundamental and Related Chapters

Please see Chaps. 1, 5, 8, 36, 38, 39, 40, and 41 for further information.

37.2Perioperative Issues in Laryngeal Framework Surgery

Vocal fold edema may have a marked effect on voice quality and prolong recovery of normal voice, thus intravenous Decadron (10 mg) is given preoperatively, followed by two additional doses at 8 and 16 h postoperatively. In rare instances, a patient undergoing framework surgery may develop laryngeal edema to such a degree that partial or complete airway obstruction occurs. Patients undergoing bilateral medialization procedures and/or arytenoid adduction are at increased risk for this complication, as are those with a history of irradiation to the neck. Generally, maximal airway edema occurs within the first 24 h after surgery; however, edema may continue to progress up to 72 h postoperatively in rare cases. All cases are admitted for overnight observation, with pulse oximetry. Patients may be fed the evening of surgery, with the diet advanced to regular as tolerated. In cases of significant postoperative edema, a peroral corticosteroid taper may be used at discharge.

Use of a surgical drain is not necessary in most medialization cases; however, with arytenoid adduction a drain is prudent. If a drain is placed, then it is typically removed the next morning before discharge.

An intravenous antibiotic such as Ancef 1 gm is given preoperatively. Postoperative antibiotics are usually not necessary unless there is a history of irradiation to the neck, in which case a fluroquinalone may be use for 7–10 days postoperatively.

Most patients have good-to-excellent voicing intraoperatively, but develop varying degrees of postoperative dysphonia as a result of edema or submucosal hemorrhage. Within hours, a good postoperative voice will become rough and hoarse. The patient should be warned of this before the surgery. The period of postoperative dysphonia is variable, but may last between 2 and 6 weeks. Rare cases may persist up to 3 months. Voice conservation is advocated; total voice rest is unnecessary.

37.3Surgical Indications and Contraindications

The principal complications specific to medialization laryngoplasty include airway obstruction and implant extrusion. The results of a survey of American otolaryngologists performed in 1998 revealed incidences generally in line with those reported in various series.

Medialization necessarily results in a narrowing of the glottic airway. In combination with postoperative edema or hematoma, this can result in significant airway obstruction—the

Fig. 37.1 Violation of ventricular mucosa at the anterior aspect of the medialization window (cross-section). Note the close proximity of the ventricular mucosa to the thyroid lamina at the anterior aspect of the window

236 |

Perioperative Care for LFS |

most dangerous postoperative complication of medialization laryngoplasty. Surgeons surveyed reported some airway compromise in 13.8% of cases. Usually, this was minor, and tended to occur more often after medialization laryngoplasty arytenoid adduction rather than medialization laryngoplasty alone. However, some 0.6% of patients undergoing medialization laryngoplasty and 2.2% of patients undergoing medialization with arytenoid adduction required intubation or tracheostomy.

Extrusion of the implant was extremely rare (0.8%) and predominantly into the airway rather than transcutaneous, as one would expect on comparison of internal and external tissue covering of the implant. It is likely that at least some of the airway extrusions, particularly those that occur within a few weeks

37 of surgery, are the result of intraoperative unidentified perforations through the mucosa. If perforation goes unrecognized at the time of surgery, then the implant is at risk for exposure and contamination. The implant then acts as a foreign body and may extrude, potentially precipitating an airway foreign-body emergency. The delicate ventricular mucosa is often located in close proximity to the inner aspect of the anterior thyroid ala, and can be easily torn when working at the anterior aspect of the window (Fig. 37.1). The key to preventing airway entry is to avoid undermining of the paraglottic space anterior to the window and to use care when removing the anterior portion of the cartilaginous window. If accidental mucosal violation does occur, then the tear can usually be closed with absorbable sutures. One can test that the closure is complete by flooding the operative field with irrigation and looking for air bubbles during a Valsalva maneuver. If the tear is successfully closed, then an implant can be safely placed in select cases. Securing the implant to the cartilage with sutures is thought to significantly reduce the risk of airway foreign body. In cases where delayed implant exposure within the airway is encountered, the patient should be taken back to the operating room for removal of the implant, either externally or endoscopically. In these cases, revision framework surgery should not be considered for at least another 3 months.

37.4Suboptimal Results/Surgical Errors

An unsatisfactory voice result rather than any airway problem or extrusion is the most common cause of revision medialization surgery. Revision rates, reported to be 5.4% in the survey of complications, can reach 16%. When secondary procedures such as fat injection are included, revision rates have been reported to be as high as 33%. Certain causes of poor voice results occur regularly and with greater frequency than others in most reported series, as well as in the authors’ experience. These include:

■Persistent posterior glottic gap

■Undermedialization

■Superior implant malposition

■Anterior implant malposition

Persistent posterior glottic gap can account for up to 50% of revisions in cases in which arytenoid adduction has not been

performed. There is some doubt that the vocal process of the arytenoid can be medialized effectively and consistently by a posterior extension of the medialization implant. Furthermore, the arytenoid and its vocal process move in three dimensions, a fact not always obvious during laryngoscopic examination, which renders height differences notoriously difficult to assess. A denervated vocal fold may thus rest at a different vertical position from its functioning counterpart. In fact, with muscle traction diminished or even absent, it may even lie outside of this trajectory, as in the case of a so-called prolapsed arytenoid, when the vocal process lies below the plane of glottic closure. Simple medialization cannot remedy a height mismatch. A height mismatch is often accompanied by unequal vocal fold tension, which causes the folds to react differently to phonatory air pressure, resulting in dysphonia.

Undercorrection is another relatively frequent cause of poor results. This is especially likely to occur in cases that last longer than usual and allow normal intraoperative vocal fold edema to accumulate. Even mild edema can create enough medial displacement of the vibratory margin of the vocal fold to cause the surgeon to underestimate of the degree of medialization required. In these cases, the patient will report good voice immediately after surgery, only to fade 1–2 weeks later, when the edema begins to resolve. The key to avoiding this complication is to keep the time from intralaryngeal elevation until final implant placement as short as possible. The window should be probed, and medialization measurements should be obtained as soon as the window is opened. In addition, preoperative intravenous corticosteroids (Decadron, 10 mg) and application of epinephrine-soaked Cottonoids within the medialization window during implant carving can help lessen edema. It is important to recognize the onset of vocal fold edema intraop-

Fig. 37.2 Flexible laryngoscopy demonstrating prolapse of the left ventricular mucosa and false vocal fold from an implant that is placed “too high” (superior to the correct plane of the long axis of the vocal fold)