Учебники / Middle Ear Surgery

.pdf

76 15 Mastoid Cavity

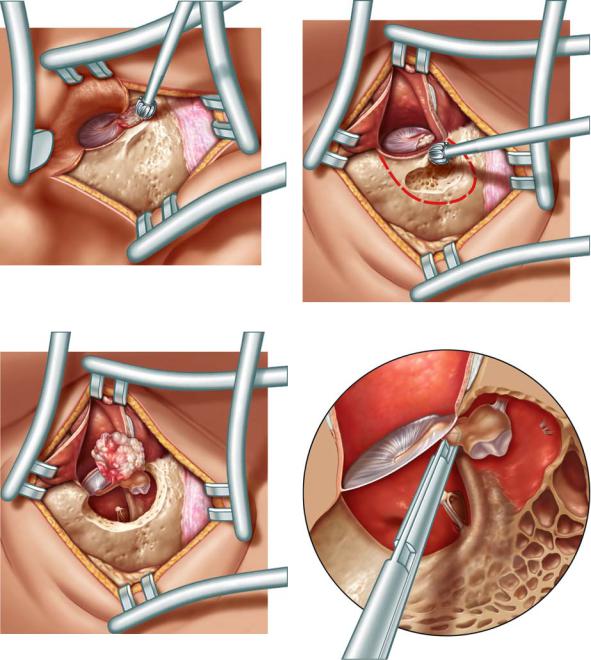

Surgical Steps

1.Retroauricular incision. This allows the removal of the tip of the mastoid and ample bone removal of the cortex if a reduction of the size of the cavity becomes necessary.

2.Preparation and removal of the tympanomeatal flap. It is reimplanted as a free graft at the end of the operation.

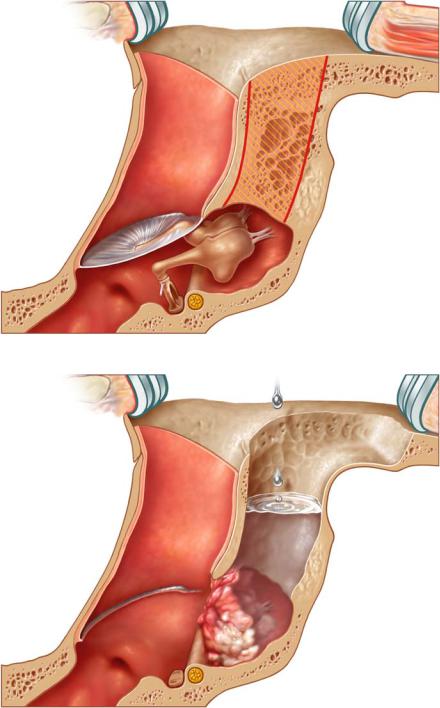

3.Widening of the ear canal (Fig. 15.3). The cholesteatoma is followed from the ear canal backwards. As long as the surgeon has no information about the condition of the chain he should avoid touching the ossicles to avoid noise trauma (Fig. 15.4). Approaching the ossicles, generally the incus and the continuity must be checked and if necessary the incudostapedial joint interrupted (Fig. 15.5).

4.The mastoid is cleaned from the cholesteatoma, trying to leave the matrix intact. The surgeon should try to stay behind the matrix and follow it if it extends into cells. The bone has to be drilled down to the facial nerve, leaving it covered by a thin layer of bone. Problem areas are the anterior epitympanum, the subarcuate tract, and the retrofacial region and perilabyrinthine cells. Niches where debris accumulates in those areas later cannot be avoided. Therefore they should be obliterated if removal of the epithelium has been complete. The epitympanum is checked and cleaned, and the head of the malleus is resected (Fig. 15.6).

15 Mastoid Cavity |

77 |

|

|

Fig. 15.3

Fig. 15.4

Fig. 15.6

Fig. 15.5

78 15 Mastoid Cavity

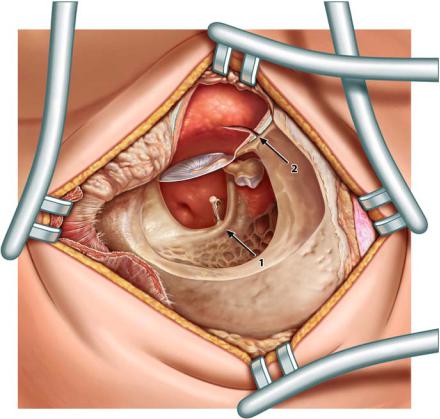

Fig. 15.7

5.The aim is a round smooth cavity (Fig. 15.7). Sharp edges are drilled off. Using a large diamond drill with little irrigation reduces bleeding. Especially in larger cholesteatomas landmarks such as the lateral semicircular canal are not reliable because the disease might erode them. Therefore the facial nerve must be identified. The disease may expose it. In a normal mastoid the lateral semicircular canal serves as a landmark. The nerve is anterior and approximately 1 mm more medially. If the cholesteatoma has destroyed some of the bone of the lateral semicircular canal, the nerve might be at the same level and can be injured. Drilling in the region of the

15 Mastoid Cavity |

79 |

|

|

Fig. 15.8

facial nerve should be parallel to the route of the nerve with a diamond drill larger than the diameter of the nerve. Constant irrigation prevents heat trauma (arrow 1, Fig. 15.8). The remnants of the tympanic membrane are lowered (arrow 2, Fig. 15.8) to allow a reconstruction in one plane at the end of the operation.

The epithelium extends rarely medially to the labyrinth. In these cases the treatment might require the destruction of the labyrinth or an additional transtemporal approach. For the less experienced surgeon it is better to interrupt the operation or ask for help.

80 15 Mastoid Cavity

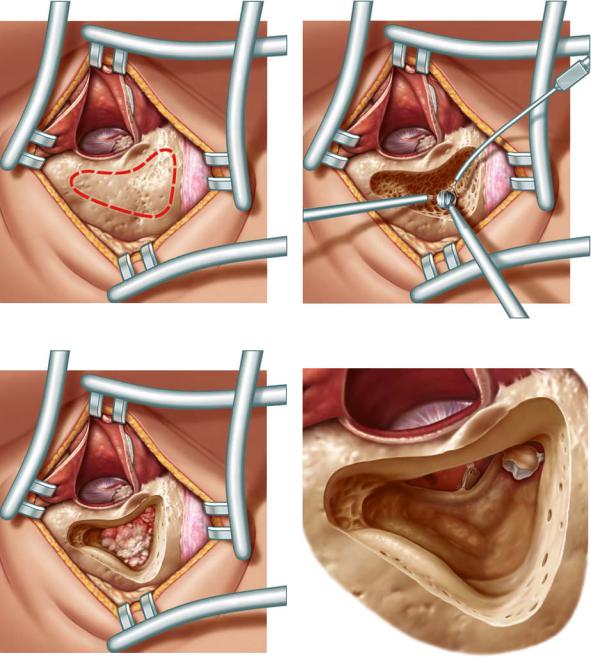

Fig. 15.9

Reduction of Volume

The only possible way of reducing the volume of a cavity without obliteration is to remove as much as possible of the outer cortex of the mastoid, the base of the zygoma and the posterior part of the tympanic bone. The bone is removed until the sigmoid sinus is seen. In addition, the tip of the mastoid with its cells can be removed (Fig. 15.9).

15 Mastoid Cavity |

81 |

|

|

Fig. 15.10

Meatoplasty

To achieve a dry cavity a good aeration by a wide meatoplasty is crucial. On the other hand, an extremely wide entrance of the outer ear canal is cosmetically unpleasant and air currents in the cavity can cause vertigo. Our routine procedure is Körner’s flap after a generous excision of the adjacent cartilage of the cavum down to the floor of the ear canal (Fig. 15.10). The flap is formed by incising the outer meatal skin at the end of the operation at about 12 and 6 o’clock. The flap is pulled backwards by subcutaneous sutures. Without cartilage excision a sufficient opening is impossible.

Pulling the flap backwards generally secures a sufficient opening. However, the procedure leaves areas uncovered with epithelium. These areas might contract during healing, reducing the size of the meatus. Therefore in revisions split-thickness skin grafts from the postauricular region and/or a pedicled flap cranially based on the preauricular or postauricular regions should provide a sufficient epithelial lining. Complete covering of the cavity with epithelium is not necessary.

Closed Techniques

As pointed out above, any technique where a direct inspection of the cavity is not possible is considered a closed technique. There are obliteration techniques on one hand and techniques preserving or reconstructing the posterior wall on the other. The reconstruction can be partial or total. Most frequently partial reconstruction techniques are used after following the cholesteatoma from the attic as described in the previous chapter.

Intact Canal Wall Technique

For treatment of cholesteatoma nowadays this technique is an exception. The number of recurrences or residuals is high especially in the hands of the inexperienced surgeon. Therefore it should only be used in cases of extensive

82 15 Mastoid Cavity

pneumatization, when a wide antrum allows a view to the posterior epitympanum and the facial recess can be drilled wide enough for a good check of the posterior middle ear. Since the same procedure is generally used for cochlear implantation, this approach will be described more extensively.

In cases with extensive pneumatization a transcortical approach with mastoidectomy is an alternative to the procedure more commonly used, following the cholesteatoma from the attic. It leaves the choice for an intact canal wall technique if the pathology permits this.

Surgical Steps

1.A retroauricular approach is used (Fig. 15.11). The bone of the mastoid is exposed and a mastoidectomy is performed (Fig. 15.12).

2.The incus and the lateral semicircular canal, if not covered with cholesteatoma, are identified and the facial recess is opened. Unfortunately, especially in more extensive disease the incus may be partially destroyed, the lateral semicircular canal might be eroded, and the bone over the facial nerve might be destroyed (Fig. 15.13). A labyrinthine fistula is possible. The epithelium is worked towards the antrum from the less dangerous regions towards the facial nerve and the semicircular canals that lie upwards from the tip of the mastoid, forwards from the sinus and posterior fossa and downwards from the middle fossa. These structures are generally covered by bone.

3.The facial nerve is identified in its mastoidal course. If anatomically possible, a diamond drill is used larger than the diameter of the nerve. The danger of injury is reduced by using a large diamond drill and by drilling in the expected direction of the nerve. The bone is thinned until the white structure with small vessels can be seen through the bone (Fig. 15.14). Bleeders and cells can cause difficulty in orientation. Polishing the cavity with a large diamond drill can control bleeding. In rare cases the nerve can pass through a cell without bony covering.

15 Mastoid Cavity |

83 |

|

|

Fig. 15.11 |

Fig. 15.12 |

Fig. 15.14

Fig. 15.13

84 15 Mastoid Cavity

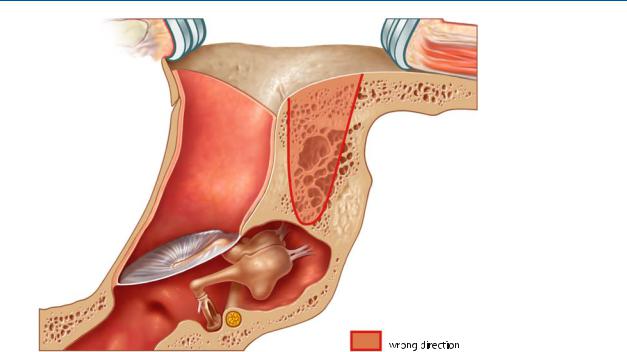

Fig. 15.15

It should be remembered that the posterior wall is not perpendicular to the surface of the mastoid. To reach the antrum the direction of drilling should be medial and forward (Figs. 15.15, 15.16). Irrigation water must flow freely from the mastoid to the middle ear. Granulations blocking the water flow must be removed (Fig. 15.17). A wide opening with identification of the landmarks – sigmoid sinus, bone on the dura of the medial fossa, the lateral semicircular canal, the facial nerve and the chorda – speeds up the surgery and avoids the risk of damage. If the bony shell of the sigmoid sinus is very prominent, the bone might be thinned, fractured (egg-shelled) and pushed backwards.

15 Mastoid Cavity |

85 |

|

|

Fig. 15.16

Fig. 15.17