Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

572 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

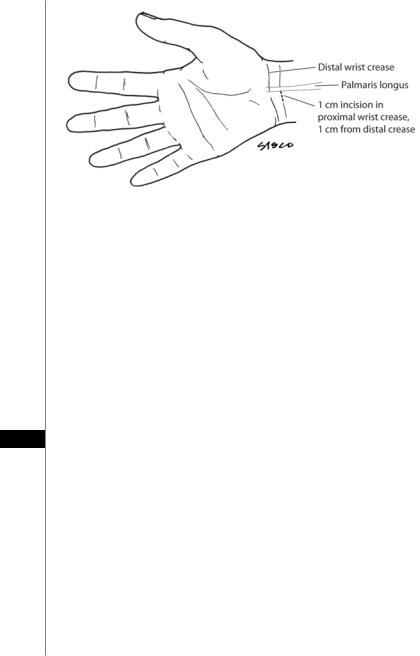

Figure 93.3. Surface markings in the endoscopic carpal tunnel release.

1.5 cm of the TCL. The blade is removed and the triangular blade is inserted through the distal portal to a point midway between the proximal and distal edge of the TCL. An incision is made large enough to accept the retrograde blade and deep enough to penetrate the full thickness of the TCL. The triangular blade is replaced by the retrograde blade, which is then used to cut the rest of the distal edge of the TCL from proximal to distal. The retrograde blade is then placed in the proximal port and engages the proximal end of the incision made in the TCL. The retrograde blade is pulled through the proximal TCL from distal to proximal. This last cut completes the release of the TCL. The obturator is replaced and the cannula system is removed. Wound closure is done with a 4-0 polypropylene subcuticular suture at the wrist and a single vertical mattress stitch at the palm. A bulky compression dressing is applied. The tourniquet is released and no splint is needed.

Complications

93Complications from carpal tunnel release are quite rare and include the following:

•Immediate Complications

–Infection—very rare

–Palmar cutaneous branch injury—most frequent nerve injury

–Nerve injury—more likely in endoscopic release

•Median nerve

•Motor branch of median nerve

•Ulnar nerve

–Vascular injury

–Tendon laceration

•Delayed Complications

–Recurrence of symptoms—in 10-20% of patients

–Incomplete release of the TCL

–Weakened grip

–Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

–Tendon bowstringing

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome |

573 |

Postoperative Considerations

After surgery, the dressing is exchanged for a light bandage and removable splint at three to seven days. Patients are encouraged to at least wear the splint when sleeping for 2 weeks after surgery as this aids in preventing tendon bowstringing. Finger motion is encouraged and early wrist motion initiated to prevent adhesions between the median nerve and surrounding tendons. Most patients return to work within 4-6 weeks after open release and within 2-3 weeks after endoscopic release. Worker’s compensation patients usually require significantly longer time (2-3 months) until they return to work.

Pearls and Pitfalls

•CTS is the most common compressive neuropathy.

•Symptoms, most often pain and paresthesias in the median nerve distribution, are often worse at night and after repetitive motion activities.

•Electrodiagnostic testing is not required in order to correctly diagnose CTS.

•Resolution of symptoms with steroid injection is associated with positive outcome with surgical treatment.

•Tell patients that pain will be relieved within days after surgery; however, motor and sensory improvement take much longer (up to 12 months).

Suggested Reading

1.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R et al. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA 1999; 282:153.

2.Katz JN, Simmons BP. Carpal tunnel syndrome. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1807.

3.Michelsen H, Posner M. Medical history of carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin 2002; 18:257.

4.Nagle DJ. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Hand Clin 2002; 18:307.

5.Steinberg DR. Surgical release of the carpal tunnel. Hand Clin 2002; 18:291.

93

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome |

575 |

The most common site of ulnar nerve compression is located just distal to the cubital tunnel proper, where the nerve traverses a tunnel between the ulnar and humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. The roof of the tunnel is referred to as Osbourne’s ligament. A small bony tubercle is palpable in the groove of the ulna just under Osborne’s ligament. Clinically, patients tend to display a sensitive Tinel’s sign at this spot. At the time of nerve decompression, the nerve tends to be “softest” at this spot, and a color change in the nerve (yellow proximal to this spot and white distal) can occur there. The fifth site of compression is point at which the ulnar nerve leaves the flexor carpi ulnaris in the proximal third of the forearm. As it exits the muscle, the nerve penetrates a fascial layer to lie between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles. The nerve can be constricted by this fascia as it traverses it producing a neuropathy.

Clinical Assessment

The symptoms of ulnar nerve compression can vary from numbness and paresthesias in the ring and little fingers to severe pain on the medial aspect of the elbow and dysesthesias radiating distally into the hand. Patients with early stages of neuropathy may not complain of any weakness although they may comment on some deterioration of hand function. Physical exam should begin at the neck. Cervical disk disease must be ruled out, as well as brachial plexus compression due to thoracic outlet syndrome. There are a number of provocative tests to evaluate for compression at these two sites. In the absence of tenderness or pain in the neck or plexus, the likelihood of significant nerve compression is low.

The elbow is inspected for deformity, and the range of motion is evaluated. The ulnar nerve is palpated along its course and in the epicondylar groove during elbow flexion for any nerve subluxation or dislocation. Local tenderness anywhere along the course of the nerve identifies a likely site of compression. A provocative test for ulnar nerve compression is the elbow flexion test, in which the elbow is placed in full flexion with the wrist in full extension for 1-3 minutes. The test is considered positive if paresthesias or numbness occur in the ulnar nerve distribution. The area of the sensory deficit can assist in distinguishing nerve compression at the elbow from one at the wrist. Ulnar nerve compression at the wrist in Guyon’s canal tends to spare dorsal sensibility because the area is innervated by the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve which branches 5-6 cm proximal to the ulnar styloid.

Sensibility testing for light touch and vibration are helpful as they reflect inner- 94 vation density which is only compromised after the presence of axonal degenera-

tion. Muscle weakness tends to occur later than numbness although occasionally inability to adduct the fifth finger (positive Wartenberg sign) is found in early presentations. Weakness affects the intrinsic muscles of the hand more often than the extrinsic muscles in the forearm. Comparing the strength of the ulnar nerve-inner- vated first dorsal interosseous muscle to the median nerve-innervated abductor pollicis brevis muscle is important.

Electrodiagnostic studies are often obtained when nerve compression is suspected but are not essential when the diagnosis is obvious on clinical exam. These tests are valuable when clinical symptoms and findings are equivocal, when the site of nerve compression is unclear or thought to be at multiple levels, or when polyneuropathy or motor neuron disease is suspected. Radiographic examination of the elbow is necessary in patients with traumatic and arthritic conditions of the elbow. The required views include the routine anteroposterior, oblique and lateral

576 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

views, and also a view imaging the epicondylar groove. Osteophytes or bone fragments from the medial trochlear lip are often seen in these patients. Magnetic resonance imaging is not an essential part of the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of ulnar nerve compression includes nerve compression which affects the origins of the ulnar nerve in the cervical spine (C8-T1 nerve roots) or the brachial plexus (medial cord). Cervical disk disease is the major cause of these conditions, followed by spinal tumors and syringomyelia. The medial cord of the brachial plexus may be compressed by thoracic outlet syndrome or a Pancoast tumor. Rarely the ulnar nerve is compressed at more than one site, a phenomenon known as “double crush” syndrome. When neural function is compromised at one level, it increases the susceptibility for nerve compression at another level, likely due to impaired axoplasmic flow. Other conditions to exclude include diabetes mellitus, vitamin deficiencies, alcoholism, malignant neoplasms and hypothyroidism.

Operative vs. Nonoperative Management

Ulnar nerve compression is classified as acute, subacute and chronic.

Acute and Subacute Nerve Compression

Acute conditions are frequently due to a single event, such as blunt trauma to the medial aspect of the elbow or an acute fracture. Subacute compression takes longer to develop. It is seen in those who continually rest on their elbows and in patients confined to bed due to illness or surgery. In these individuals, nerve compression usually improves if the nerve irritation is reversed. Nonoperative management includes patient education to avoid elbow flexion and prolonged pressure at the elbow, and splinting. Splints are worn for three to four weeks and removed only for bathing. The course of splinting is followed by active range-of-motion exercises. NSAIDs may be prescribed, but steroid injections are avoided. Patients with no muscle weakness who opt for nonoperative care are reassessed regularly for muscle strength. Progressive weakness is an indication for surgery whether or not there is a change in symptoms.

Surgical intervention becomes necessary if conservative care fails to relieve local tenderness, numbness or paresthesias. In the absence of muscle weakness, however,

94there is no urgency to surgical intervention. If activities of daily living, work, or leisure-time activities are compromised-in the absence of any meaningful improvement with conservative treatment, then surgery is recommended. Patients with mild muscle weakness that persists for three to four months have an indication for surgery as well.

Chronic Nerve Compression

Those patients presenting with chronic neuropathy associated with weakness frequently fail nonoperative management and require surgery. Factors influencing successful surgical outcome include patient age, the duration of nerve compression, and the severity of muscle weakness and numbness. The worst prognosis is seen in those with muscle atrophy, severe weakness, and patients with sensibility deficits in innervation density and two-point discrimination. Such patients may have minimal or no improvement in sensation or strength following surgery if the neuropathy is that far advanced.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome |

577 |

Operative Treatment

Decompression of the ulnar nerve can be performed with or without nerve transposition. Decompression without transposition typically refers to a localized surgery where the ulnar nerve passes through the cubital tunnel, namely, between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The surgery involves sectioning Osborne’s ligament. The decompression should be limited distally to reduce the risk of nerve subluxation. The limit of dissection is the line drawn from the medial epicondyle to the tip of the olecranon. The entire surgery can be carried out under local anesthesia and involves limited dissection. The ideal patient for this surgery is one who presents with recurrent symptoms of ulnar neuropathy due to swelling of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle with repetitive activities (e.g., violionists), as well as findings localized to the cubital tunnel. Decompression in situ proximal to the epicondylar groove is not commonly performed. It is indicated in cases of hypertrophy of the medial head of the triceps (typically seen in bodybuilders) and if snapping of this medial head with elbow flexion leads to symptoms. Decompression in situ is contraindicated for severe cases of ulnar nerve compression, particularly in posttraumatic scarring, when the nerve should be transferred to an unscarred area.

In the mid 1950s, the treatment of ulnar neuropathy by decompression accompanied by medial epicondylectomy was popularized. This was advocated because it was felt that a transposed nerve could still be irritated by slipping onto the apex of the medial epicondyle. The disadvantages of this procedure are that it fails to release the most distal potential sites of compression and it does not relieve traction forces on the nerve as effectively as transposition. Over-excision of the epicondyle can destabilize the elbow by damaging the medial collateral ligament which can lead to a postoperative valgus deformity. Despite these potential disadvantages, medial epicondylectomy is effective in mild cases of cubital tunnel. It is a relatively quick and simple surgery that avoids direct trauma or manipulation of the nerve.

Nerve decompression with transposition is the most popular method of treatment of cubital tunnel, and it has several theoretic advantages. First, the nerve is removed from its irritated location and repositioned to a new site. Second, the nerve is effectively lengthened several centimeters by transposing it into a new volar pathway. There are three locations for ulnar nerve transposition: subcutaneous, intramuscular, and submuscular.

Subcutaneous transposition is the most commonly used method because of its

ease and high success rate. This method is ideal for the elderly, the obese and in patients 94 with arthritic joints. The disadvantages of this method are that it fails to decompress

the nerve at the most distal site and the nerve remains vulnerable to repeated trauma. Intramuscular transposition is the most controversial of the three approaches.

Proponents claim it has less scarring than submuscular transposition while others have found scarring to be a common complication. Advocates also feel that the intramuscular position offers more protection than the subcutaneous location. Submuscular transposition has several advantages. It insures that all five potential sites for nerve compression have been explored and allows repositioning of the nerve in an unscarred location where there is no influence from traction or external compressive forces. This method of transposition requires greater dissection and can potentially cause more nerve ischemia. Another drawback to submuscular transposition is the risk of an elbow flexion contracture while waiting for the flexor-prona- tor muscle group to heal. Submuscular transposition is contraindicated when there is scarring of the joint capsule or a joint distorted by arthritis or malunion.

578 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Surgical Technique

Whichever technique is chosen, there are some basic steps that tend to be followed consistently. The operation is performed under regional or general anesthetic. Local anesthesia can be used only for decompression in situ without nerve transposition. Additionally, the surgery should be performed under tourniquet. For the three types of transposition (described below), the incision begins 8 to 10 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle. The medial intermuscular septum is palpated, and the incision is made directly over it. The incision continues along the epicondylar groove and ends 5 to 7 cm distal to the epicondyle over the course of the ulnar nerve. When dissecting through the subcutaneous tissue, one must be sure to protect the posterior branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. It can be found within 6 cm of the epicondyle, either proximal or distal to it. Along the course of the ulnar nerve, the fascia immediately posterior to the medial intermuscular septum is incised. In succession, the fibroaponeurotic covering of the epicondylar groove is released, followed by Osborne’s ligament at the cubital tunnel, and the fascia of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The fibrous edge of the medial intermuscular septum is excised especially near the epicondyle where the septum is thicker and wider. Care is taken when mobilizing the nerve to minimize traction on it. The ulnar nerve is dissected free along a distance of 15 cm, from the arcade of Struthers to the deep flexor pronator aponeurosis. Epineurolysis may be performed in areas where the epineurium is thickened.

Subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve requires that it be secured in its new position in a stable fashion. This prevents the nerve from slipping back into the epicondylar groove. Creating a fasciodermal sling is the preferred method. A flap based near the medial epicondyle is created and reflected medially. The flap is passed posterior to the nerve and anchored to the subcutaneous tissue with a suture. Alternatively, the flap may be based and reflected laterally. The joint is immobilized postoperatively with the forearm in pronation and the elbow bent at 90˚ (some surgeons advocated splinting at 45˚) for two weeks, followed by hand therapy.

Intramuscular transposition involves creating a trough in the flexor-pronator muscle mass with division of the fibrous bands to provide a suitable bed for the ulnar nerve. Submuscular transposition requires the entire flexor-pronator muscle mass to be detached from its origin. There are several means of performing this, including dividing the tissue in a Z-plasty approach, leaving a 1 cm cuff of tissue on

94the bone to ease reattachment, and removing the muscle sharply from bone. The muscle can even be removed along with a portion of the medial epicondyle. Following detachment, the flexor carpi ulnaris is released for a short distance from the ulna distal to the insertion of the collateral ligament. The ulnar nerve is transferred onto the bed of the brachialis muscle proximal to the joint line and on the capsule of the joint distally. The nerve branch to the flexor carpi ulnaris is often dissected away from the main body of the ulnar nerve to prevent its tethering or kinking. Finally, the flexor-pronator muscle mass is reattached to the medial epicondyle. The tourniquet is deflated, hemostasis obtained, and the subcutaneous tissue closed. A posterior splint is applied with the wrist in neutral position, the forearm in neutral rotation, and the elbow flexed at 45˚. The patient is immobilized for one week, followed by active range of motion exercises. Most patients resume full activity by 10 weeks post surgery although for sports that require throwing up to 6 months of therapy may be needed.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome |

579 |

Pearls and Pitfalls

•The initial treatment of acute and subacute neuropathy is nonoperative; for chronic neuropathy associated with muscle weakness or other symptoms that do not improve with conservative treatment, surgery is often required.

•Treatment is most successful in those with mild neuropathy.

•Subcutaneous nerve transposition is the least complicated technique. It is the preferred approach in the elderly and in neuropathy due to an acute fracture, elbow arthroplasty, or for secondary neurorrhaphy.

•Medial epicondylectomy for ulnar nerve decompression tends to have a high recurrence rate, though the surgery is quick and effective in mild cases.

•Intramuscular transposition can be associated with severe postoperative perineural scarring.

•Submuscular transposition is the preferred method for most chronic neuropathies that need surgery. It also the preferred approach when prior surgery has not been successful.

Suggested Reading

1.Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg [Am] 1989.; 14(6):972-9.

2.Matev B. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand Surg 2003; 8(1):127-31.

3.Mowlavi A, Andrews K, Lille S et al. The management of cubital tunnel syndrome: A meta-analysis of clinical studies. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 106(2): 327-34.

4.Posner MA. Compressive ulnar neuropathies at the elbow: I. Etiology and diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998; 6(5):282-8.

5.Tetro AM and Pichora DR. Cubital tunnel syndrome and the painful upper extremity. Hand Clinics 1996; 12(4):665-77.

94

Trigger Finger Release |

581 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

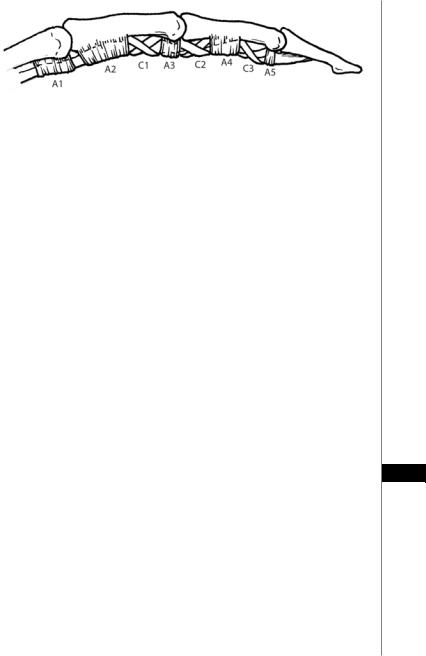

Figure 95.1. The annular and cruciate pulley system of the digital flexor sheath. The pulleys are numbered from proximal to distal. Note that most triggering occurs at the A1 pulley.

Grading

The degree of pathology occurs along a continuum, classified into four grades primarily based on the existing impairment of excursion:

Grade 1—Pretriggering

The mildest presentation involves only nodularity of the tendon sheath without any difficulty in tendon gliding. An inflamed area of tendon is usually palpable, tender to exam, and may be crepitant. Patients often report initially bumping something during grasp and still feeling persistent soreness along the tendon for weeks after.

Grade 2—Active Triggering

The next grade includes clicking or “catching”, which is nonlocking (actively correctible). The name “trigger finger” derives from the nonlinear effort involved with this kind of flexion, similar to the trigger mechanism of a firearm.

Grade 3—Passive Triggering

This grade involves consistent locking of the digit during flexion that is only correctable by passive means (usually the opposite hand is used). Note that even in this grade, passive flexion causes minimal tendon excursion and will not cause locking.

Grade 4—Incarceration

When the nodularity of the tendon is greater than the diameter of the flexor sheath and/or pulleys, a digit is described to be incarcerated, or locked. Failure to promptly release this stage (i.e., within 24 hours) can result in permanent impairment of motion 95 if the digit is permitted to scar in place. Often these can be reduced with slow, even, sustained passive traction and then managed as a lower grade lesion.

Treatment

Management of trigger finger, or stenosing tenosynovitis, can be divided into closed, percutaneous and open treatment.

Closed Treatment

Corticosteroid injection is the mainstay of treatment for triggering, as it improves the size discrepancy between the tendon and its enclosure, primarily by reducing the swelling of the tendon. The effectiveness of one injection has been reported in the 70–80% range for resolving triggering. A second injection raises the cure rate to 85% for first time sufferers with isolated early grade triggering. Steroid effect