Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

532 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Superficial infection, especially in grossly contaminated injuries, is the most common postoperative complication. It is usually treated with intravenous antibiotics; however debridement is sometimes necessary.

Late complications of vascular repair include pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas. The brachial artery is a common site of postrepair pseudoaneurysm. This places the hand and fingers at risk from thromboembolic events. These usually require resection with saphenous vein graft interposition. Nerve injuries are another late complication that can be seen with vascular injuries at any level of the arm since the named vessels often travel in close proximity to major nerves. Nerve injury can be iatrogenic at the time of surgery or as a result of postoperative swelling or scarring at the site of repair. The most likely scenario, however, is that the nerve injury occurred at the time of the injury and was not diagnosed on the initial evaluation. Finally, minor long-term complications include hand weakness, paresthesias and cold sensitivity.

Pearls and Pitfalls

•Any vein that cannot be easily repaired should be clipped. There is no vein in the upper extremity that is essential. Even the axillary vein can be ligated if the repair will prolong the surgery excessively and place the patient at greater risk.

•One cannot over-emphasize the importance of a tension-free repair. Tension on the intima at the site of repair increases the risk of thrombosis and tearing of the vessels. If this cannot be achieved, a vein graft should be used. Outcomes using a vein graft are almost equivalent to direct repair.

•An arterial repair should always be reinspected following any manipulation of the limb (e.g., after fracture reduction or fixation).

•Prophylactic fasciotomy of the forearm and median nerve decompression should

88strongly be considered after revascularization of an arm that has been completely ischemic for more than 4 hours.

Suggested Reading

1.Aftabuddin M, Islam N, Jafar MA et al. Management of isolated radial or ulnar arteries at the forearm. J Trauma 1995; 38(1):149.

2.Busquets AR, Acosta JA, Colon E et al. Helical computed tomographic angiography for the diagnosis of traumatic arterial injuries of the extremities. J Trauma 2004; 56(3):625.

3.Dennis JW, Frykberg ER, Veldenz HC et al. Validation of nonoperative management of occult vascular injuries and accuracy of physical examination alone in penetrating extremity trauma: 5- to 10-year follow-up. J Trauma 1998; 48(2):243.

4.Fitridge RA, Raptis S, Miller JH et al. Upper extremity arterial injuries: Experience at the Royal Adelaide Hospital, 1969 to 1991. J Vasc Surg 1994; 20(6):941.

5.Frykberg ER, Crump JM, Dennis JW et al. Nonoperative observation of clinically occult arterial injuries: A prospective evaluation. Surgery 1991; 109(1):85.

6.Johansen K, Lynch K, Paun M et al. Noninvasive vascular tests reliably exclude occult arterial trauma in injured extremities. J Trauma 1991; 31(4):515.

7.Rich N, Mattox K, Hirshberg A, eds. Vascular Trauma. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2004.

8.Schwartz M, Weaver F, Yellin A et al. The utility of color flow Doppler examination in penetrating extremity arterial trauma. Am Surg 1993; 59(6):375.

9.Zellweger R, Hess F, Nico A et al. An analysis of 124 surgically managed brachial artery injuries. Am J Surg 2004; 188:240.

534 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

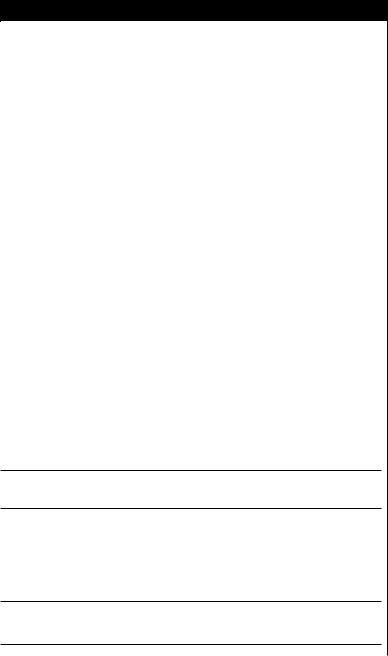

Figure 89.1. The extensor tendon mechanism.

Intrinsic Musculature

The intrinsic apparatus includes the dorsal interosseus muscles, the volar interossei, and the lumbricals. The four dorsal interossei insert onto the proximal

89phalanges and abduct the fingers and weakly flex the proximal phalanx. The three volar interossei do not attach to bone but rather insert onto the lateral bands that unite with the lateral slips of the extensor tendons. They adduct the fingers and flex the PIP joint. The lumbricals arise from the tendon of FDP on the palmer side and insert onto the radial lateral band of each finger. They primarily extend the IP joints and function as flexors of the MP joints. The intrinsic muscles are innervated primarily by the ulnar nerve, except for the first and second lumbricals, which are innervated by the median nerve. The intricate extensor, flexor and intrinsic systems are interconnected, aligned and stabilized with a system of ligaments found in each finger. The triangular, transverse retinacular and oblique retinacular ligaments perform a variety of complex actions. The pathology of these ligaments is addressed in the chapter on Dupuytren’s disease. A detailed discussion of their functions is listed at the end of this chapter (see Suggested Reading).

Blood Supply

The extensor tendons are supplied by a number of sources. Vessels from the muscles and bony insertions travel distally and proximally, respectively, down the length of the paratenon. The dorsal aspect of the tendon is not as well vascularized as the deeper surface which receives branches from the periosteum and palmar digital arteries. Unlike the flexor tendons, the extensors have no vincular system. Synovial diffusion plays a major role in the delivery of nutrients, less so than in the flexor tendon system.

Extensor Tendon Injuries |

535 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

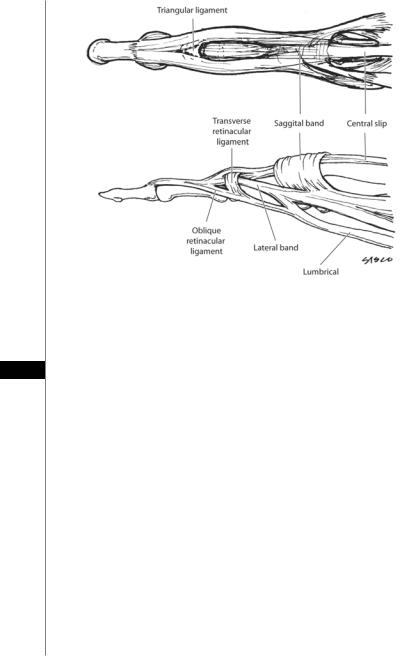

Figure 89.2. The zones of extensor tendon injury in the fingers and hand.

Zones of Injury

The dorsum of the fingers, hand and wrist can be divided into zones of injury for describing the location of tendon injury (Fig. 89.2). The odd numbered zones over-

lie the joints, whereas the even numbered zones overlie the bones. Injuries in zones 89 2, 3, and 4 of the fingers, and zone 7 in the wrist have a worse prognosis. Extensor tendon lacerations in all zones should be repaired primarily. Little to no tendon retraction occurs in injuries in zones 1-4. Proximal to the MP joints, however, ten-

don retraction will occur.

Zone 1 and 2 injuries (DIP and middle phalanx) can produce a mallet finger deformity. Zone 3 and 4 injuries (PIP and proximal phalanx) can produce the boutonniere deformity. These deformities and their treatment are discussed below. Zone 5 injuries (MP joint) can divide the sagittal band and displace the tendon laterally. The sagittal bands should be repaired. Injuries in this zone will usually cause the tendon stump to retract proximally. Zone 6 injuries of the dorsal hand may not result in loss of extension due to transmission of force from adjacent tendons through the juncturae. In zone 7 injuries of the wrist, the injured retinaculum should be excised, but the proximal or distal portion should be preserved in order to prevent bowstringing of the tendon.

Primary Suture Repair

Extensor tendons become very thin and flat in the hand, making their repair difficult. They can easily fray during repair. Many suture techniques have been described for primary repair of extensor tendons. Simple lacerations of the extensor tendon in zone 1 can be repaired with a figure-of-eight stitch. A number of biomechanical studies support using the Kleinert modification of the Bunnell technique. The modified Kessler technique is also commonly used. The chapter on

536 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

flexor tendon repair illustrates and discusses these repairs in greater detail. Following primary repair of extensor tendon injuries, the finger should undergo dynamic splinting in extension for 4-6 weeks. Partial lacerations of less than 50% can usually be managed by wound care, and splinting for several weeks followed by active motion.

Tendon Rupture

Rupture of tendons in the nonrheumatoid hand usually occurs 6-8 weeks following fractures of the distal radius or carpal bones. Infection and attacks of gout also increase the risk of rupture. Tendons in the nonrheumatoid hand will rupture at the musculotendinous junction or at the bony insertion. Rarely will they rupture within the substance of the tendon itself. The most commonly ruptured tendons are the EPL at Lister’s tubercle, as well as EDM and EDC to the little finger. Tendon ruptures cannot be repaired primarily in most cases, and tendon transfers are required. EPL rupture is usually treated with transfer of the EIP tendon or palmaris longus or interposition autograft. Rupture of the tendons to the little finger can be repaired by suturing the distal stump of the intact tendons of the ring finger. If the extensor muscles have not undergone contracture, tendon grafts are also an option. When performing flexor to extensor transfer, it is important to remember to transfer the tendons subcutaneously rather than below the retinaculum since wrist flexion occurs in synergy with finger extension.

Tendon Loss

Loss of segments of an extensor tendon can occur in severe burn, crush, or degloving injuries of the dorsum of the hand. Direct primary repair is generally not possible, and tendon transfers or grafts are required. Transfers can be done with both extensor and flexor tendons. A vascularized palmaris longus tendon can be transferred using a pedicled radial forearm fascial flap. A variety of free flaps containing vascularized tendons have been described. A composite dorsalis pedis free

89flap has been used with good results obtained. Staged tendon reconstruction with Hunter rods is also an option. Whatever technique is chosen, immediate reconstruction is preferable to a staged repair.

Postoperative Considerations

Rehabilitation

The traditional approach of static splinting without mobilization has largely been abandoned. Dynamic splinting with controlled motion is now standard of care. Many splints have been described. Most involve splinting the wrist in extension and allow the injured finger to extend passively and partially flex against rubber band resistance. Many studies have shown that early controlled motion decreases the incidence of postoperative adhesions and post-traumatic deformities. Proximal injuries (zones 5-7) benefit more from dynamic splinting than distal ones. Children and adults who are unable to cooperate with postoperative hand therapy should undergo static splinting.

Adhesions

Adhesions following lacerations can occur between the tendon and bone, especially if there are underlying fractures. The hallmark is limitation of PIP extension and flexion—due to dorsal tethering. Adhesions should be treated with 6 months of active assisted motion exercises. If this fails, tenolysis may be indicated. Adhesions proximal

Extensor Tendon Injuries |

537 |

to the MP joint can also be treated with extrinsic extensor release, providing that the intrinsic muscles are intact. In this release, the extrinsic tendon central slip is excised just proximal to the PIP joint. Consequently, the PIP joint will be extended solely by the intrinsic muscles, and the extrinsic tendon will extend only the MP joint.

Post-Traumatic Deformities

Mallet deformity describes DIP flexion and inability to extend the joint. It results from disruption of the extensor mechanism at the distal phalanx. Injuries can be classified into discontinuity of the extensor tendon (rupture or laceration), avulsion of the tendon from its distal insertion, or fractures of the distal phalanx. Closed injuries can cause this deformity as a result of forced passive flexion of the DIP joint. If treatment is not pursued, a secondary swan-neck deformity can occur. Treatment consists of continuous immobilization of the DIP in slight hyperextension for 6-8 weeks using a splint or by percutaneous, Kirschner wire fixation. Surgical treatment should be reserved for those who fail conservative management or for fractures requiring open reduction. Surgical options include direct tendon repair, tendon grafting, arthrodesis, and a number of other reconstructive techniques.

Swan-neck deformity describes PIP hyperextension and DIP flexion. It is the progression of a mallet deformity left untreated, as a consequence of disruption of the distal extensor mechanism. The PIP joint progressively extends since all of the force of the extrinsic extensor tendon is transmitted to the PIP joint through the central slip. The DIP joint progressively flexes due to lack of extensor force combined with unopposed FDP pull on the distal phalanx. With time the volar plate becomes lax at the PIP joint. The swan-neck deformity does not respond well to conservative management, and surgical repair is usually required. Along with repair of the extensor mechanism and any avulsion fractures, the contracted intrinsic muscles and PIP joint collateral ligaments should be released. In addition, the volar plate must also be tightened. Kirschner wires are removed at 4 weeks postoperatively, and a dorsal blocking splint is generally

applied at that point. Arthrodesis and arthroplasty are reserved as salvage procedures. 89 Boutonniere deformity describes PIP flexion and DIP/MP hyperextension. It

occurs as a result of injury to the central slip over the PIP joint and volar migration of the lateral bands. This deformity is manifest at about 2-6 weeks postinjury, therefore any trauma to the PIP region should include an evaluation of the extensor tendon. Swelling of the finger can mask a developing Boutonniere deformity. In such cases, the finger should be splinted in extension and examined a few days later after the swelling decreases.

Treatment consists of splinting the PIP joint in extension for 6 weeks. The DIP joint should be mobilized during this period to aid in dorsal migration of the lateral bands. Surgical treatment is indicated for avulsions of large bony fragments from the middle phalanx, PIP joint instability and dislocation that cannot be reduced, or extensive soft tissue loss to the dorsum of the finger. The central slip can be reconstructed from the remaining extensor mechanism (e.g., centralizing portions of the lateral bands) or with a tendon graft. Postrepair splinting should be done for 2 weeks. Arthrodesis is indicated for salvage of severely injured fingers. Amputation is occasionally required for severe injuries.

Intrinsic-plus contracture describes scarring of the interosseous muscles. This occurs post-traumatically, and can be prevented by minimizing edema of the hand (elevation, ice, NSAIDs, etc), and splinting the hand in the intrinsic-plus (safe) position: MP flexion, IP extension and palmar abduction of the thumb. Intrinsic muscle necrosis and subsequent fibrosis can occur shortly after trauma to the hand.

538 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

The finding of pain on passive extension of the MP joints is an early sign of impending intrinsic muscle death. Treatment of intrinsic-plus contracture consists of conservative splinting first, followed by surgical release when necessary. The interosseous tendons can be severed at the proximal phalanx. If MP flexion contracture is present, however, the release should be performed at the musculotendinous junctions.

Post-traumatic adhesions can form between the interossei and the lumbricals distal to the transverse metacarpal ligament. Patients with this condition will present with pain upon fist-making or on forceful finger flexion. These adhesions should be dealt with surgically as soon as they are recognized. Finally, lateral band contractures after trauma can also occur. When present they can impair DIP flexion with passive PIP extension. The involved band should be excised.

Pearls and Pitfalls

•A patient who presents with a mallet finger (zone I injury), irrespective of the duration of injury, can usually be treated in a closed fashion with splinting alone. This has a high likelihood of success even in cases with a delayed presentation of weeks to months. A stiff finger may require sequential progression of the splinting of the DIP joint towards the extended position.

•A laceration in the vicinity of the DIP joint is at risk for having entered the joint space. This raises the likelihood of joint infection which can lead to failure of the repair. Delayed tendon repair should be considered in these patients.

•Zone III lacerations involving the PIP joint often involve the central slip or lateral bands, and these should be repaired. If the laceration is very close to the insertion of the central slip, there may be insufficient length of distal slip to suture. In this case, a tunnel can be created in the dorsal distal phalanx using a K-wire through which the suture ends can be passed and tied.

•Extensor tendon lacerations over the MP joints (zone V) are often due to human bites (either biting or striking an open mouth) whether the patient admits this or

89not. Such wounds are at very high risk of infection and the tendon should never be repaired primarily. It can be repaired a week later after the wound is no longer contaminated.

•Ruptured tendons (most commonly EPL) may present many months to years after injury. In some cases, the muscle belly has atrophied or fibrosed, and tendon transfer should be performed. Only if there is evidence of a functioning muscle should the tendon be repaired with a tendon graft.

Suggested Reading

1.Blair WF, Steyers CM. Extensor tendon injuries. Orthop Clin North Am 1992; 23:141.

2.Browne Jr EZ, Ribik CA. Early dynamic splinting for extensor tendon injuries. J Hand Surg 1989; 14:72.

3.Kleinert HE, Verdan C. Report of the committee on tendon injuries. J Hand Surg 1983; 8:794.

4.Landsmeer JMF. The anatomy of the dorsal aponeurosis of the human finger and its functional significance. Anat Rec 1949; 104:31.

5.Masson JA. Hand IV: Extensor tendons, Dupuytren’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. Selected Readings Plast Surg 2003; 9(35):1-44.

6.Newport ML, Williams CD. Biomechanical characteristics of extensor tendon suture techniques. J Hand Surg 1992; 17A:1117.

7.Rockwell WB, Butler PN, Byrne BA. Extensor tendon: Anatomy, injury, and reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 106:1592.

8.Verdan CE. Primary and secondary repair of flexor and extensor tendon injuries. In: Flynn JE, ed. Hand Surgery. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1975.

|

540 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

|

|

|

to attach to the middle phalanx. The FDP tendon, after passing through the FDS |

|

|

|

||

|

|

bifurcation, attaches to the distal phalanx. |

|

|

|

Flexor pollicis longus (FPL) is the primary flexor of the thumb. It is the most radial |

|

|

|

structure in the carpal tunnel. It travels in its own fibrous sheath in the palm and |

|

|

|

inserts into the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. The thumb, unlike the fingers, |

|

|

|

has two annular pulleys, A1 and A2, located over the MP and IP joints, respectively. |

|

|

|

Lying between them is an oblique pulley that is the most important of the three. |

|

|

|

Blood Supply |

|

|

|

The tendons have a rich vascular supply. Longitudinal vessels travel along the |

|

|

|

dorsal length of the tendons. The paired digital arteries supply segmental vessels to |

|

|

|

the sheath via the short and long vincula. Finally, the synovial fluid within the ten- |

|

|

|

don sheath allows oxygen and nutrients to diffuse along its length since there are |

|

|

|

several short avascular zones over the proximal phalanx. The motion of the tendon |

|

|

|

facilitates the imbibition that delivers the nutrient-rich synovial fluid. |

|

|

|

Biomechanics |

|

|

|

In the neutral wrist position, only 2.5 cm of flexor tendon excursion is needed to |

|

|

|

produce digital flexion. As the wrist is flexed, the amount of tendon excursion re- |

|

|

|

quired to flex the digits is more than tripled. Anything that causes the tendon to |

|

|

|

become flaccid and to bowstring, such as loss of an annular pulley, will result in |

|

|

|

greater excursion requirements to produce flexion. The A2 and A4 pulleys are the |

|

|

|

most important in this regard. Loss of either one will result in a substantial reduc- |

|

|

|

tion in motion and power and a risk of flexion contracture of the digit. Rupture of |

|

|

|

the pulleys can be diagnosed with clinical exam, ultrasound or MRI. |

|

|

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

|

History |

|

90 |

|

In obtaining the history, the posture of the hand at the time of injury should |

|

|

|

be determined. Injuries that occur with the fingers extended will result in the |

|

|

|

distal end of the tendon being located close to the wound. In contrast, injury to a |

|

|

|

flexed finger will result in the distal tendon retracting away from the wound as the |

|

|

|

finger is straightened. |

|

|

|

Clinical Examination |

|

|

|

Alterations in the normal resting position should be noted. Separate evaluation of |

|

|

|

both FDP and FDS function is important. Division of the FDS without injury to the |

|

|

|

FDP will not be noticeable in the resting posture. However, lacerations on the palmer |

|

|

|

surface of the fingers will usually sever the FDP tendon before the FDS tendon. FDS |

|

|

|

is evaluated by immobilizing the surrounding fingers in extension and having the |

|

|

|

patient flex the finger at the PIP joint. It is critical to isolate each joint since without |

|

|

|

DIP isolation the common muscle belly to the ulnar FDP digits may generate mock |

|

|

|

flexion at an adjacent PIP joint. FDS to the index finger is evaluated by having the |

|

|

|

patient perform a firm pulp-to-pulp pinch with the thumb. An injured FDS will cause |

|

|

|

as pseudo mallet deformity of the distal phalanx whereas an intact FDS will result in a |

|

|

|

pseudo boutonniere deformity of the distal phalanx. FDP is evaluated by immobiliz- |

|

|

|

ing the PIP and IP joints, and evaluating flexion of the isolated DIP joint. |

|

|

|

A complete sensory exam of the palmar surface is important since trauma to the |

|

|

|

digital nerves can occur with tendon injuries. Two-point discrimination should be |

|

Flexor Tendon Repair |

541 |

performed on both the radial and ulnar aspect of each finger. The presence of nerve injury can influence the choice of incision used for exposure. Deep lacerations that disrupt the digital nerves can also sever the digital arteries. The finger can sometimes survive with intact skin even in the presence of bilateral digital artery disruption. However, at least one artery should be repaired if the tendon is also injured in order to avoid ischemia and impaired healing.

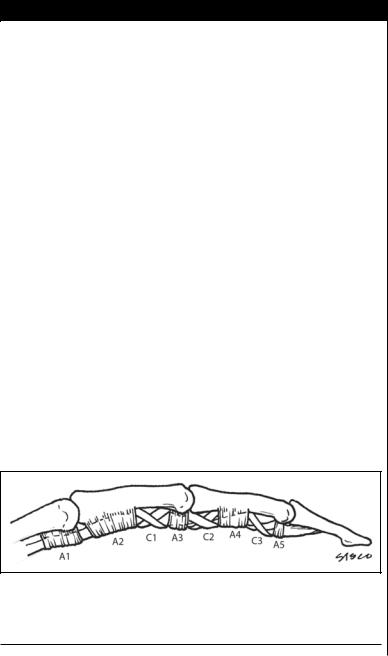

Indications for Repair

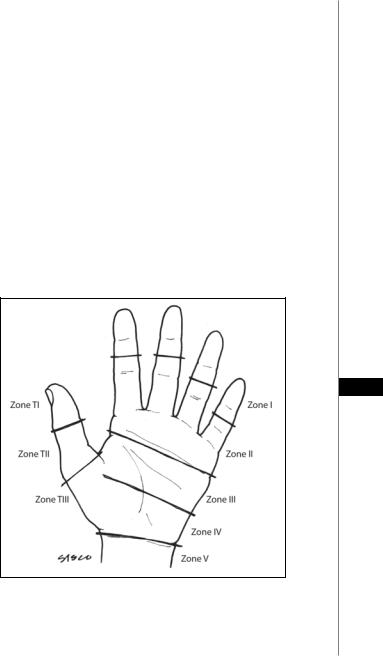

Dividing the hand into zones of injury (Zone I-V) is an internationally accepted method of classifying the location of flexor tendon injury (Fig. 90.2). As a general rule, complete flexor tendon lacerations in both the palm and the digital sheath should be repaired. Partial tendon lacerations greater than 60% should be repaired. In the past, zone II was referred to as “no man’s land,” since primary repair resulted in poor functional outcome. However, modern techniques have allowed the repair zone II injuries primarily.

Flexor tendon injury is not a surgical emergency; delayed primary repair (up to two weeks post-injury) can provide good long-term results. However, early repair is preferable. Although the early literature recommended against repairing FDS, most surgeons now repair both the FDP and FDS tendons. This is true for all zones of injury. Tendon repair should be attempted after bony fixation and revascularization have been achieved. Nerve repair should also be attempted when feasible.

90

Figure 90.2. The zones of flexor tendon injury in the hand. Zone I is distal to the FDS insertion; zone II is from the A1 pulley to the FDS insertion; zone III is from the carpal tunnel to the A1 pulley; zone IV is the carpal tunnel; zone V is proximal to the carpal tunnel. The thumb is divided into three zones: TI is distal to the IP joint and T2 is distal to the MP joint.