Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

422 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Poor Scarring

Patients with the highest risk of poor scar outcome are cigarette smokers and any patients with comorbidities that predispose them to microvascular disease. Closing wounds in a tension free manner offers the best chance for optimal scar outcome. If the surgeon anticipates a tight skin closure below the NAC, then extrapigmented skin may be left inferiorly and excised at a later time. Horizontal incisions commonly heal with hypertrophy due to the amount of tension on these wounds. Efforts to minimize incision length combined with proper wound taping may help limit hypertrophic scarring. If hypertrophic scarring does occur, silicone gel therapy or steroid injections should be attempted prior to scar revision.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Choosing a periareolar technique for significant ptosis will result in poor scarring, deformity of the nipple and recurrence. The vertical mastopexy approach may allow a sufficient lift; however, the use of a variable length of horizontal incision in conjunction with this may allow for the necessary removal of excess skin. A modification of the vertical mammaplasty is the use of a curvilinear J-type incision. This may obviate the need for a short horizontal scar for more moderate forms of ptosis. An adjunctive internal suspension of the breast parenchyma may be necessary with these approaches depending on the quality of skin and its ability to be an active element in shaping and holding form. With the Benelli approach, care must be taken with preoperative counseling about the scar and the relatively long process of smoothening of contours. While concomitant implant placement may improve not only ptosis but also the overall aesthetic result, it is critical to judiciously evaluate the timing of implant placement in light of patient expectation and anatomy. In some instances it may be more prudent to stage the augmentation and mastopexy.

Suggested Reading

1.Bostwick IIIrd J. Augmentation mammaplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing Inc., 2000:239-369.

2.Benelli L. A new periareolar mammoplasty: The “round block” technique. Aesth Plast Surg 1990; 14(2):93.

3.Regnault P. Breast ptosis: Definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg 1976; 3(2):193.

4.Rohrich RJ, Thornton JF, Jakubietz RG et al. The limited scar mastopexy: Current concepts and approaches to correct breast ptosis. Plast Roconstr Surg 2004; 114(6):1622.

5.Spear SL, Little III rd JW. Reduction mammoplasty and mastopexy. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. 5th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1997.

6.Weinzweig J. Augmentation mammaplasty. Plastic Surgery Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley, 1999:238.

68

Chapter 69

Abdominoplasty

Amir H. Taghinia and Bohdan Pomahac

Classification and Choice of Procedure

Procedures used to change the shape of the anterior abdomen include liposuction (suction-assisted lipectomy), mini-abdominoplasty (infraumbilical elliptical skin and fat excision), abdominoplasty and panniculectomy. Patient selection and preference determines which operation to perform. A thorough history and physical examination usually reveals the best operation for a given patient. The physical examination should determine the amount of excess skin, the amount of excess subcutaneous fat and the laxity of abdominal fascia. Classification schemes have been developed to assist the surgeon in decision-making:

Type 1 Fat deposit with normal fascia and skin liposuction only

Type 2 Mild excess skin, normal fascia with or without excess fat infraumbilical elliptical skin excision with liposuction for excess fat

Type 3 Mild excess skin, infraumbilical fascia laxity with mild to moderate fat excess

infraumbilical elliptical skin resection, infraumbilical fascia tightening and liposuction or direct lipectomy

Type 4 Mild excess skin, total fascia laxity with or without excess fat infraumbilical elliptical skin excision, supraand infraumbilical fascia tightening and liposuction or direct lipectomy for excess fat

Type 5 Large excess skin, total fascia laxity with or without excess fat complete abdominoplasty with supraand infraumbilical fascia tightening

In general, abdominoplasty addresses excess skin and lax abdominal fascia whereas liposuction addresses only excess fat. The ideal abdominoplasty patient has excess skin, mild excess fat and mild to moderate fascia laxity (Type 5). In contrast, the ideal abdominal liposuction patient has excess fat with normal, taut fascia and taut skin (Type 1). Liposuction alone is not recommended for patients with lax or excess skin. In these patients, liposuction without concomitant skin excision results in an unsightly ‘deflated balloon’ look.

The mini-abdominoplasty is reserved for patients with mild excess skin with or without excess fat (Types 2, 3 and 4). An infraumbilical ellipitical skin and fat excision is performed. If the infraumbilical fascia is lax (Type 3), it may be tightened directly.

Panniculectomy is removal of excess abdominal wall tissue (skin and fat) without associated undermining or umbilical transposition. It is usually performed in previously massively obese patients who have lost weight. These patients have a large segment of overhanging abdominal skin and fat. The “pannus” can lead to problems with skin breakdown or panniculitis. These patients have poor vascularity of the abdominal wall tissue; therefore even limited flap undermining can lead to complications.

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

424 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Patients with excess abdominal wall fat usually benefit from weight loss prior to an operation. Successful preoperative weight loss heralds a motivated patient and

69promises a pleasing outcome. Certain patients will present with a somewhat bulging abdomen with minimal to moderate excess abdominal wall fat, normal fascia and no excess skin. Typically these patients will have significant excess intraabdominal fat. Weight loss is encouraged in these patients as well.

Preoperative Considerations

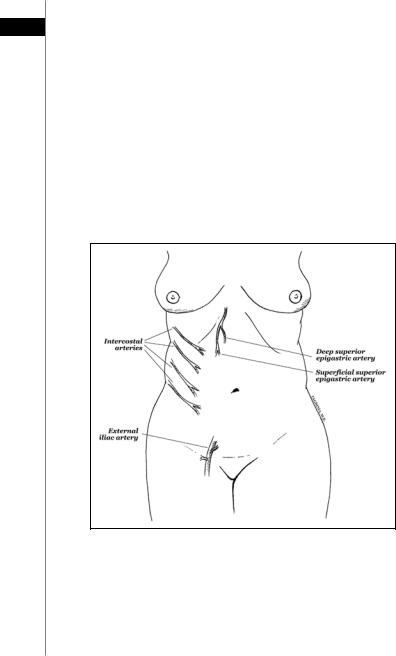

In the preoperative setting, the surgeon should pay close attention to the unique needs, characteristics and concerns of the patient. A thorough history and physical examination is crucial—not only to determine the surgical strategy but also to uncover potential sources of future complications. Previous abdominal surgery should raise the possibility of incisional hernias. Scars from prior abdominal surgery may also indicate the need for a more conservative approach. For example, an oblique right upper quadrant incision (e.g., from a previous open cholecystectomy) indicates potential interruption of the superolateral blood supply to the abdominoplasty flap (Fig. 69.1). The astute surgeon may consider flap delay, minimal undermining,

Figure 69.1. Blood supply to the anterior abdominal wall. The superficial epigastric artery perfuses the abdominal skin directly. The deep epigastric arteries (inferior and superior) perfuse the abdominal skin and subcutaneous tissue via perforators through the rectus abdominus muscle. Once fully raised, the abdominoplasty flap receives its main blood supply from the deep superior epigastric and intercostal arteries. A subcostal right upper quadrant incision (e.g., from an open cholecystectomy) can interrupt the superolateral blood supply to the abdominal wall. Liposuction of the lateral abdominoplasty flap can jeopardize blood supply from the lateral intercostal vessels.

Abdominoplasty |

425 |

restrained resection, or a combination of these approaches. Smoking should be stopped at least 1 month prior to surgery. Aggressive resection in smokers invites complications. 69

Hernia repair during abdominoplasty needs to be considered carefully. Occasionally, hernia repair requires extensive lysis of adhesions. Possible bowel injury during these operations may result in significant wound infections. In addition, these patients inevitably endure a longer hospital stay (for return of bowel function), thus providing a set up for other complications such as deep vein thrombosis and hospital-acquired infections.

Suction-assisted lipectomy during abdominoplasty can lead to feared complications of flap necrosis and infection. It is important to note that raising the abdominoplasty flap disrupts the blood supply from the deep superior and inferior epigastric perforators (Fig. 69.1). Thus, the predominant blood supply to the lower flap comes from the laterally-based segmental perforators of the intercostals vessels. Lateral liposuction of the abdominoplasty flap can injure these vessels, thus compromising blood supply of the flap, especially in the lower midline watershed area. Liposuction should not be performed in the lateral abdominoplasty flap. When done in the midline or inferior far-lateral flanks, it should be done very conservatively and in experienced hands.

Operations and Techniques

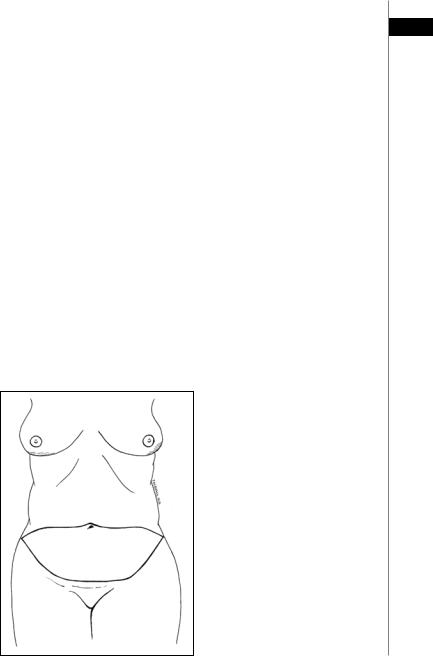

With the patient standing, the midline is determined. A pinch test is performed to determine the amount of excess skin. The lower border of the dissection is marked at a point 5-7 cm above the vulvar commissure. Lines are drawn laterally curving up to the anterior superior iliac spines. The superior borders of excision are then drawn laterally from a point just above the umbilicus. The superior lines serve only as useful guides for preliminary planning-rarely do they determine the final extent of excision (Fig. 69.2).

Figure 69.2. Markings for abdominoplasty. The lower incision is made and the flap is elevated. The superior markings serve as a guideline and may be modified once the flap is raised and redraped.

426 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

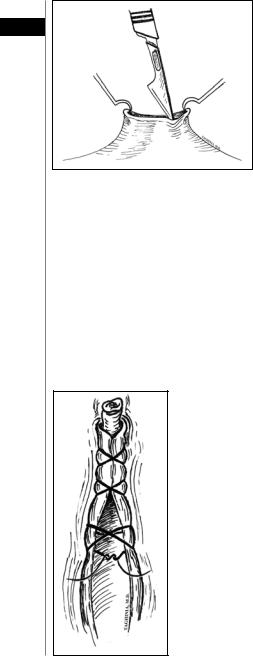

Figure 69.3. Umbilical incision. Two skin hooks elevate the umbilicus and 69 provide tension for making the incision. An 11-blade incises the umbilicus circumferentially. The incision is then carried down to the fascia using heavy curved scissors to cut the fibrous bands that tether the

umbilicus (not shown).

The patient is placed in the supine position with arms abducted. An intravenous antibiotic is administered, and pneumatic compression boots are fitted. After induction of adequate general anesthesia, a Foley catheter is inserted and the abdomen is prepped and draped from the xyphoid to the pubis. Abdominoplasty can also be performed under sedation and local anesthesia.

The umbilicus is sharply circumscribed and dissected down to the anterior abdominal wall fascia (Fig. 69.3). The inferior incisions are made and carried to the fascia. Injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is avoided by leaving a small amount of redundant fat attached to the anterior superior iliac spine. The dissection is directed cephalad towards the xiphoid along the plane anterior to the abdominal fascia. Perforating vessels must be identified and coagulated before being divided or they can retract and may cause delayed hematomas.

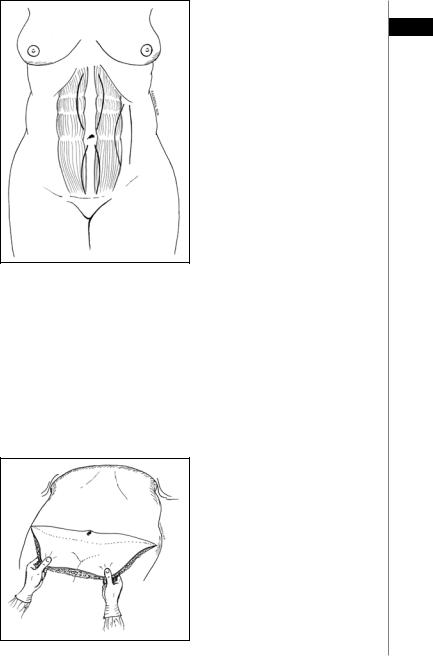

If the abdominal fascia is lax, it may be tightened with running or figure-of-eight interrupted nonabsorbable sutures (Fig. 69.4). This tightening is usually performed

Figure 69.4. Fascial plication. Buried, nonabsorbable figure-of-eight interrupted sutures approximate the fascia in the midline below the umbilicus. A running, heavy gauge suture can also be used.

Abdominoplasty |

427 |

Figure 69.5. Tightening patterns for complete abdominoplasty. Vertical midline curves are drawn and approxi- 69 mated above and below the umbili-

cus. Alternatively, tightening can be performed at the linea semiluminaris (the intersection of rectus fascia and external oblique fascia).

at the midline above and below the umbilicus depending on the degree of laxity (see classification scheme). Arguing that the lax midline fascia may not support tightening in the long-term, some authors prefer to plicate the fascia laterally at the linea semiluminaris (the adjoining border of the external oblique and rectus fascia as shown in Fig. 69.5).

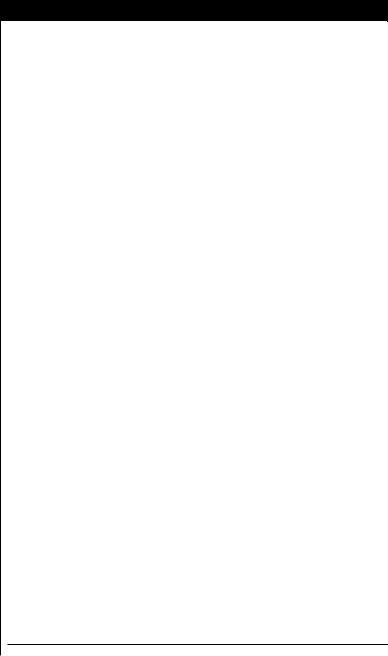

The patient’s hips are flexed and the excess skin of the flap is excised (Figs. 69.6, 69.7). It is crucial to avoid excessive skin removal that could cause undue tension on the closure. The new site for the umbilicus is determined, and an opening is made to accommodate the umbilicus. In general, a smaller umbilicus looks more natural and less conspicuous. Most surgeons err towards a smaller, more inferiorly positioned umbilicus. Some prefer a vertical incision for the umbilical opening whereas others prefer a V-shaped incision (Fig. 69.8).

Figure 69.6. Gauging excess tissue. Once the flap is fully raised, the patient’s hips are flexed and the flap is pulled inferiorly to assess the amount of excess tissue to be excised.

428 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Figure 69.7. Gauging excess tissue. The lower flap can be cut in half to 69 provide better visualization of excess

tissue-especially in the midline.

Figure 69.8. Techniques for umbilicoplasty. Some surgeons prefer a V-shaped incision (A) whereas others prefer a short vertical incision (B). The umbilical stalk may be sutured to the periumbilical anterior fascia (not shown).

If there is significant excess fat in the flap, it can be directly excised from below Scarpa’s layer. To accentuate the midline, fat may be directly excised from the sub-Scarpa’s layer in the midline. At this point, careful hemostasis is achieved. The flap is brought down, and the umbilicus is housed in its new location. Jackson-Pratt closed suction drains are placed through stab incisions in the pubic area. It is important to reapproximate Scarpa’s fascia prior to dermal closure. The flap and umbilicus are then closed with interrupted deep dermal and running subcuticular sutures.

Postoperative Care

Patients are admitted to the hospital overnight and are discharged to home the following day. The hospital bed is kept in the semi-Fowler position and ambulation is encouraged with hips flexed. Intermittent intravenous analgesia usually provides adequate pain relief until patients are able to tolerate oral pain medications. Ice packs applied to the suprapubic region can also provide good pain relief. The Foley catheter is removed at midnight prior to discharge. Voiding difficulties can be handled early in the day thus allowing timely discharge. Patients are discharged with pain medication, antibiotics and instructions for Jackson-Pratt drain care. While at home,

Abdominoplasty |

429 |

|

|

patients monitor and record drain output. The drains are usually removed after a |

|

||

week during the first office visit. At that point, activity is gradually increased until |

|

||

69 |

|||

full return to activities, including sports and heavy lifting, at six to eight weeks. |

|

||

|

|||

Complications |

|

|

|

Fortunately, worrisome complications of abdominoplasty rarely occur. These |

|

||

include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and major skin necrosis. The |

|

||

more common complications of abdominoplasty include seroma, infections, he- |

|

||

matoma and minor skin edge necrosis. Infections should be treated with antibiotics |

|

||

and debridement of nonviable tissue. Small hematomas self-absorb and may be ob- |

|

||

served. Larger hematomas should be treated more aggressively by open or percuta- |

|

||

neous drainage. Observation is usually warranted for most seromas. Large seromas |

|

||

may be drained percutaneously, but often times the fluid reaccumulates. Minor skin |

|

||

edge necrosis is treated with conservative debridement and, if necessary, late scar |

|

||

revision to improve cosmetic appearance. |

|

|

|

Pearls and Pitfalls

•Design of the skin incision should take into consideration patient preference. Some women wear very low-riding pants, and an incision that approaches the iliac crest may be visible.

•The larger caliber, periumbilical perforating vessels should be cauterized and transected well above the level of the fascia so that if one bleeds it will not fully retract into the rectus muscle below. If this occurs, a figure-of-eight suture should be used to achieve hemostasis.

•Any palpable bulge on the fascia will be a visible one on the surface when the patient stands and should be tightened. Occasionally this may involve horizontal tightening of the fascia.

•Plication of the fascia should span from xyphoid to pubis, otherwise a bulge will occur above or below the tight suture line.

•Many surgeons use tacking sutures to help adhere the abdominoplasty flap to the fascia in order to reduce dead space. This has the theoretical benefit of decreasing seroma formation.

•Never make the superior skin incision until there is no doubt that the skin will close without undue tension. It is better to have a small vertical scar (from the umbilicus incision) than central skin necrosis or hypertrophic scarring from excess tension.

Suggested Reading

1.Bozola AR, Psillakis JM. Abdominoplasty: A new concept and classification for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 1988; 82(6):983-93.

2.Grazer FM, Goldwyn RM. Abdominoplsty assessed by survey with emphasis on complications. Plast Reconstr Surg 59(4) :513-7.

3.Greminger RF. The mini-abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1987; 79(3) :356-65.

4.Hester Jr TR, Baird W, Bostwick IIIrd J et al. Abdominoplasty combined with other major surgical procedures: Safe or sorry? Plast Reconstr Surg 1989; 83(6):997-1004.

5.Lockwood TE. High-lateral-tension abdominoplasty with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995; 96(3):603-15.

6.Lockwood TE. Maximizing aesthetics in lateral-tension abdominoplasty and body lifts. Clin Plast Surg 2004; 31(4):523-37.

7.Pitanguy I. Abdominal lipectomy. Clin Plast Surg 1975; 2(3):401-10.

Chapter 70

Liposuction

Zol B. Kryger

Indications

Liposuction, or suction-assisted lipectomy, is the most common plastic surgical procedure performed in the U.S. It is used for removal of fat from small to moderately localized deposits; however many surgeons now perform large-volume liposuction for more generalized fat removal. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction has a role in treating gynecomastia and other deposits of tough, fibrous fat. These include lipodystrophy due to protease inhibitors (submental and “buffalo hump”) and benign lipomatosis. There are reports of treating lipomas, lymphedema and post-rhytidectomy hematomas or fat necrosis with liposuction.

Relevant Anatomy

Liposuction is performed on subcutaneous adipose tissue, which can be divided into superficial, intermediate and deep layers. The superficial layer is composed of denser fat with organized fibrous septa. The deep layer is more loosely arranged with areolar fat and minimal fibrous tissue. The intermediate layer is a transition between the two. Most liposuction is performed on the deep and intermediate layers. Removing fat from the superficial layer is associated with a risk of skin irregularities and contour deformities. Some surgeons will create several closely spaced tunnels using small diameter cannulas in the superficial fat layer without suctioning. This can help the skin retract and scar down to the underlying tissue in order to avoid irregularities in the skin. Superficial lipectomy should not be done on the buttocks.

A study by Rohrich et al described the term “zones of adherence” where liposuction should be avoided:

•Lateral gluteal depression (just superior to the “saddle bags”)

•Gluteal crease

•Posterior thigh above the popliteal fossa

•Inferolateral iliotibial tract region

•Medial mid-thigh

In these areas, the skin is tightly adhered to the underlying fascia, and contour

deformities are more likely to occur.

Preoperative Considerations

Liposuction is a significant surgical procedure; there are several potentially serious complications. Patients should be ASA class I and within 30% of their ideal body weight. Many patients have expectations that cannot be met by liposuction alone. A detailed discussion of the risks, including the likelihood of contour irregularities requiring a secondary procedure, is essential.

After consideration of the anatomical factors listed above, patients should be marked while they are standing upright. A common technique used for marking is

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Liposuction |

431 |

|

|

|

|

to use to use a topographical map-like sytem in which the area to be suctioned is |

|

marked with concentric rings. An increasing number of rings indicates a greater |

|

thickness of fat to be suctioned. The areas to be avoided are marked as well. Prior to |

70 |

surgery, an intravenous antibiotic in given. |

Tumescent Technique

Almost all liposuction is performed after injection of tumescent solution. Tumescent solution is typically composed of 0.9% saline containing 0.05–0.1% lidocaine and 1:1,000,000 epinephrine. Several liters of this solution are introduced into the area to be suctioned 10-20 minutes prior to starting. The local anesthetic effect of the lidocaine reduces the need for heavy sedation or general anesthesia. The epinephrine assists in hemostasis and slows the absorption of the lidocaine, allowing a dose of up to 35 mg/kg to be used. The typical volume of tumescent solution used is three times the volume of fat to be aspirated.

Liposuction Techniques

Syringe Aspiration. Small volume liposuction can be performed using a syringe with the plunger withdrawn. This technique is excellent for harvesting small amounts of fat for soft-tissue augmentation. It is a controlled technique and can be used to remove fat from the superficial layer.

Suction-Assisted Lipectomy (SAL). Often referred to as “traditional” liposuction, this technique relies on the energy generated by the longitudinal motion of the surgeon’s hand. The speed of the movement, the size of the cannula, and the characteristics of the suctioned fat combine to determine the rate of liposuction. When the surgeon’s hand is still, there is no effect on the tissue because no kinetic energy is generated.

Power-Assisted Liposuction (PAL). An external motor is used to generate reciprocating motion of the suction cannula, thus sparing the surgeon from the repetitive motion of manual liposuction. This significantly reduces surgeon fatigue at the expense of a small amount of control. Studies demonstrate equivalent cosmetic results with PAL compared to traditional liposuction.

Ultrasound-Assisted Liposuction (UAL). This technique relies on the delivery of ultrasonic waves that liquefy the fat, making suctioning more efficient. Since the cannula generates heat, one must constantly keep it in motion when on. Care must be taken not to burn the skin, resulting in “end hits.” Since UAL removes fat quickly, most surgeons achieve the final contour with traditional or power-assisted liposuction. The second generation UAL device, the VASER system, emits pulsed waves instead of continuous waves of energy. This reduces the heat of the probe by about 50%, decreasing the risk of thermal injury.

Complications

Minor complications from liposuction occur in 10% of cases and include:

•Infection

•Contour irregularities

•Hypesthesia (which usually resolves within 6 months)

•Skin sloughing

•UAL skin burns

•Skin discoloration

•Seroma or hematoma