Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

392 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

dramatically. Clinically, the signs and symptoms include acute pain, proptosis, chemosis and opthalmoplegia. The globe and lid may become hard to palpation. Acute orbital hemorrhage is a medical and surgical emergency. An emergency ophthalmology consult should be obtained, but treatment should not be delayed. Treatment includes immediate suture removal, wound exploration and lateral canthotomy. Mannitol, acetazolamide and steroids may be administered to reduce intraocular pressure. Anterior chamber paracentesis and bony orbital decompression are rarely used.

Diplopia

Diplopia in the early postoperative period is not uncommon. It may be caused by edema or anesthesia infiltration of the extraocular muscles. Long-lasting diplopia is extremely rare and may be caused by damage to the inferior oblique muscle, which is especially vulnerable during the transconjunctival approach. Management is supportive.

Ptosis

Post-blepharoplasty ptosis occasionally occurs secondary to edema and ecchymosis. In these cases the ptosis is temporary and usually resolves after 2-3 weeks. However, the most frequent cause of postoperative ptosis is the failure to recognize it preoperatively. Early postoperative asymmetry is best managed by time and gentle massage of the higher crease. Ptosis lasting longer than 3 months requires reexploration.

Scleral Show

The incidence of scleral show is reported to be as high as 15% in some series. Many surgeons suggest the principle cause of lower eyelid malposition is unrecognized laxity in the tarsoligamentous sling. In addition to scleral show, ligamentous laxity tends to cause rounding of the lateral palpebral fissure. Treatment is conservative with massage therapy for 2-3 months. The round eye appearance may improve slowly with time and gentle upward massage. Lateral canthopexy can be done if symptoms persist. It is important to remember that minimal skin should be excise in a lower blepharoplasty.

Ectropion

Although ectropion is one of the most commonly discussed complications of lower blepharoplasty, its incidence is estimated to occur in less than 1% of patients. The best treatment is prevention by attention to lower lid laxity and conservative

63skin and orbicularis excision. Ectropion is usually treated by massage therapy and taping for at least 3 months. If the ectropion persists, tightening procedures or skin grafts can be performed.

Lagopthalmos

Lagopthalmos is the inability to completely close the eyes. It occurs immediately after surgery due to swelling and local anesthesia impairment of orbicularis oculi function. Lagopthalmos requires treatment with eye lubricants to protect the cornea and reduce irritative symptoms. Persistent lagopthalmos is probably related to the amount of skin excised from the upper lid and not the amount of muscle excised. In most cases, lagopthalmos resolves as the wound matures.

Blepharoplasty |

393 |

Dry Eyes

Mild dry eye syndrome secondary to lagopthalmos is a common transient problem. However, it can produce corneal ulcerations that may threaten vision. All patients should be provided with ocular lubricants.

Pearls and Pitfalls

It is important to identify ptosis preoperatively. Possible causes of ptosis include trauma, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, Horner’s syndrome, myasthenia gravis, levator dehiscence and upper lid tumors. Pseudoptosis is excess skin that causes hooding and depression of the upper lid. Pseudoptosis can be differentiated from true ptosis by elevating the excess skin with a cotton-tipped applicator. Ptosis, particularly asymmetric ptosis, should be highlighted for the patient preoperatively. Operative correction is dictated by the cause of ptosis.

Preoperative testing for dry eyes (e.g., Schirmer’s tests) may have a poor positive predictive value. The best predictors of postoperative dry eyes are abnormal ocular history or abnormal orbital anatomy. Abnormal ocular anatomy includes: scleral show, lagopthalmos, lower lid hypotonia, proptosis, exopthalmos and maxillary hypoplasia. Patients with one or more of these anatomic findings should be provided with additional preoperative warnings and postoperative ocular protection.

Although ectropion is uncommon, the surgeon must have a high preoperative index of suspicion. Ectropion may be prevented by a variety of lateral canthal tightening procedure. The senior author prefers a Kunt-Simonowsky lid shortening procedure for lower risk patients and a lateral canthopexy for higher risk patients. Correcting an ectropion is more difficult than preventing an ectropion.

Suggested Reading

1.Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Preoperative evaluation of the blepharoplasty patient: Bypassing the pitfalls. Clin Plast Surg 1993; 20:213.

2.Rees TD, LaTrenta GS. The role of the Schirmer’s test and orbital morphology in predicting dry-eye syndrome after blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1988; 82:619.

3.Zarem HA, Resnick JI. Operative technique for transconjunctival lower blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 1992; 19:351.

4.Zide BM. Anatomy of the eyelids. Clin Plast Surg 1981; 8:623.

63

Chapter 64

Rhinoplasty

Ziv M. Peled, Stephen M. Warren and Michael J. Yaremchuk

Introduction

Nasal surgery requires careful analysis of the patient’s problems, detailed planning and meticulous operative technique. Specific nasal problems must be detailed in order to understand the patient’s likes and dislikes about the nose. External and internal examinations are necessary to understand the complex three-dimensional anatomy and define the aesthetic and functional problems. Rhinoplasty is a procedure in which subtle changes in anatomy often make profound differences in appearance, making this one of the most challenging yet elegant procedures in the plastic surgery. Although rhinoplasty is a complex procedure, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), over 350,000 rhinoplasties were performed in the United States in 2003, making it one of the most common cosmetic surgical procedure.

Anatomy

To begin to understand the complexities of rhinoplasty, one must first become familiar with nasal anatomy. This understanding is often hampered by the plethora of terms used to describe the anatomy of the nose. This chapter will attempt to underscore the key components of nasal anatomy, how these components interact functionally, and how they are affected during nasal surgery. In the process, we will try to maintain a consistent nomenclature to avoid confusion.

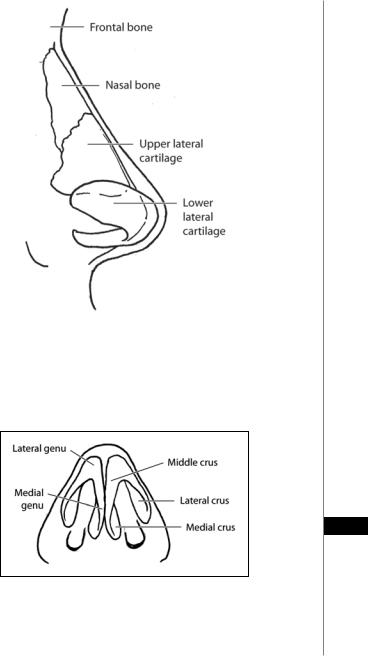

Beginning cephalically, the nose consists of a pair of nasal bones that extend caudally from the frontal bone (Fig. 64.1). These bones function as a structural support extending from the skull. Posteriorly, the nasal bones are supported by the anterior edge of the frontal process of the maxilla on either side. Caudally, the nasal bones fuse with the dorsal septum forming a support structure that extends along the length of the nasal dorsum. Moving towards the tip, the caudal aspect of the nasal bones overlaps the cephalic portion of the upper lateral cartilages for a distance of 2-4 mm. The upper lateral cartilages comprise the distal nasal sidewalls and extend towards the tip of the nose. At their caudal free edge, they are overlapped by the cephalic portions of the lower lateral cartilages.

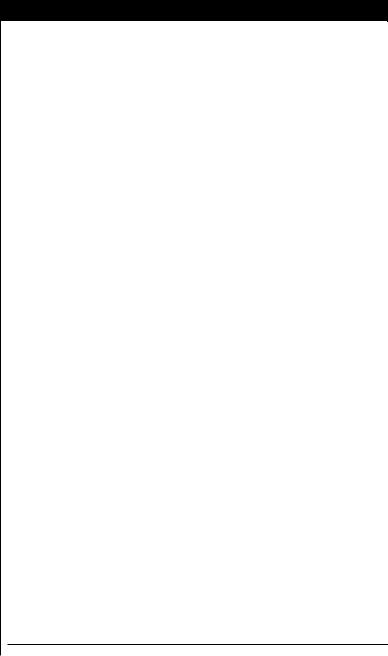

The lower lateral cartilages are also known as the alar cartilages. They provide the structural support to the soft tissues of the lower third of the nose, also known as the tip or lobule, which is also the portion of the nose which has the greatest projection from the facial skeleton. The lower lateral cartilages are subdivided into three parts (Fig. 64.2). The portions of the lower lateral cartilages closest to the midline on either side are known as the medial crura. They comprise the structural support for the columella. At their most posterior aspect, they flare slightly laterally to form the medial footplates which project into the nasal vestibule. More anteriorly, are the

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Rhinoplasty |

395 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 64.1. Lateral view of the nose illustrating the relationship between the frontal bones, nasal bones, and the upper and lower lateral cartilages. Note also the superior location of the lateral extent of the lateral crus on the patient’s right side demonstrating that the lateral aspect of the alar lobule is devoid of cartilage. (Reproduced with permission from “Aesthetic Rhinoplasty” by J.H. Sheen, 1998, Quality Medical Publishing.)

64

Figure 64.2. Components of the lower lateral cartilages. Note the slight projection of the posterior-most portion of the medial crura into the nasal vestibule. This portion of the medial crura is also known as the medial footplate. (Reproduced with permission from “Aesthetic Rhinoplasty” by J.H. Sheen, 1998, Quality Medical Publishing.)

396 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

middle crura which continue from the most anterior portion of the medial crura towards the tip of the nose and begin the turn laterally to form part of the genu (i.e., curve) of the lower lateral cartilages. The lateral crura comprise the remainder of the genu by continuing laterally, posteriorly and slightly cephalically. It is important to note that as one traces the lateral crura from the tip posterolaterally, the crura project more cephalically (Fig. 64.1). Hence, the lateral crura provide structural support to the nasal rim predominantly at their medial portions, leaving the very lateral portions of the nasal alae devoid of cartilage. This portion of the nose is comprised of fibrofatty tissue covered by overlying skin.

The nasal septum is composed of three structures: the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid posteriorly and cephalically, the vomer posteriorly and caudally and the quadrangular (i.e., cartilaginous) septum anteriorly. The septum functions as a support structure for the mid-portion of the nose and it also comprises the medial component of the internal nasal valve (completed posteriorly by the nasal floor and laterally by the upper lateral cartilages). The average internal valve angle is 12˚.

The arterial anatomy of the nose is important to consider for several reasons. While the blood supply to the nose is abundant making tissue necrosis a rare complication, the potential for clinically significant bleeding exists. Bleeding can be significant in that it can compromise tissue due to compression (e.g., septal hematoma) or compromise visualization during the rhinoplasty. Again, beginning cephalically, the blood supply to the dorsal nose is derived from the dorsal nasal artery and the external nasal branches of the anterior ethmoidal artery. The lateral nasal artery which arises from the angular artery supplies blood flow to the nasal sidewalls and the caudal nasal dorsum and tip. The columellar branches of the superior labial artery anastomose with the distal branches of the lateral nasal artery to supply the nasal tip from below. The blood supply to the septum comes from the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, the sphenopalatine artery and the posterior septal artery. The convergence of the anterior and posterior ethmoidal plexuses in the anterosuperior septum is known as Little’s area and is the most common site of injury causing epistaxis. Because of its location, the anterior ethmoidal artery is the most often injured in nasal trauma.

The cutaneous nerve supply to the nose is important because adequate local analgesia can allow the plastic surgeon to perform a rhinoplasty without general anesthesia. Since the local anesthetics contain epinephrine, appropriate infiltration can also reduce blood loss. Furthermore, the local anesthetics can be used to hydrodissect delicate nasal tissues facilitating subsequent sharp dissection. For example, local anesthesia infiltrated submucosallly in the septal area, not only provides excellent hemostasis, but also separates the septal mucosa from the underlying cartilaginous septum. Beginning cephalically, the nasal branches of the supraorbital nerve

64are infiltrated to anesthetize the radix and proximal nasal dorsum. Sensation along the nasal sidewalls, alae and columella is blocked using local anesthesia on the nasal branches of the infraorbital nerve. The middle and distal thirds of the nasal dorsum as well as the tip of the nose are anesthetized by blocking the external nasal branches of the anterior ethmoidal nerve. The anterior septum is blocked by anesthetizing the medial and lateral branches of the anterior ethmoidal nerve. If a septoplasty will be performed in addition to the rhinoplasty, the nasopalatine and posterior nasal nerves, which supply sensation to the posterior septum medially and laterally, respectively, should be blocked. Once the nose is adequately blocked, the rhinoplasty procedure can begin.

Rhinoplasty |

397 |

Surgical Technique

Whether to perform an open or a closed rhinoplasty remains a controversial topic. To be sure each technique has its advantages and disadvantages and these, along with the requests of the patient, should be used to guide the surgical approach. The open rhinoplasty involves any of a variety of mid-columellar incisions to expose the nasal anatomy much like one would expose the engine of a car by opening the hood. Clearly, the advantages of this approach are the excellent visualization which facilitates the operative procedure and teaching. Disadvantages include the external scars, the longer operative time and the increased postoperative swelling secondary to more aggressive manipulation of the nasal tissues. During a closed rhinoplasty, no external incisions are made and access to the nasal framework is obtained via any number of internal incisions (e.g., inter-, intraor infracartilage, or rim). Advantages with this technique are the lack of external scarring and the relative expeditiousness of the procedure. Its primary disadvantage is the limited visualization which therefore limits the manipulations than can be performed. This approach is best suited for patients requiring minor tip work, straight-forward resection of a prominent dorsal hump, or those with a wide alar base.

Dorsal Hump

One of the most common complaints is a prominent dorsal hump. In consideration of the anatomy just reviewed, one can understand that this prominence can be caused either by projecting nasal bones, upper lateral cartilages, cephalic dorsal cartilaginous septum or some combination thereof. Resection of this dorsal hump can be performed either with the closed or open rhinoplasty technique. Once the overlying soft tissues have been dissected in the subcutaneous plane from the underlying bony and cartilaginous anatomy, the reason(s) for the projecting dorsum can be determined. While many techniques are used to achieve a more balanced nasal dorsum, the general principles are to sharply resect the cartilaginous components of the dorsal hump and to use either an osteotome or rasp to resect the bony dorsum. The rasp is generally used for more subtle bony adjustments. Two points about dorsal hump resection deserve emphasis. First, conservative resection is best. One can always resect more and as noted earlier, small changes often make pronounced differences in appearance. Secondly, it is important to avoid resection of the mucoperichondrium as this tissue layer provides support to the upper lateral cartilages and can lead to an inverted-V deformity.

Tip Projection

Under-projection of the nasal tip is another common problem. Tip projection can be enhanced in a number of ways. A transdomal suture bringing the genua closer together will add a mild degree of projection. Placement of an onlay tip graft

can enhance tip projection as well as widen the nasolabial angle and increase lobular 64 volume. Other ways of achieving the same effect are placement of a columellar strut

graft and suturing the medial footplates together. In addition, lowering a dorsal hump will often give the impression of a cephalically oriented tip. Each of these techniques has its unique degree of tip enhancement and differing effects on surrounding nasal structures (e.g., columella, lobule, upper lip).

The over-projecting tip (Pinocchio nose) is due to excess length of the medial and lateral crura. Resection of the medial or lateral crura or scoring of the dome-medial crura junction with or without resection of the lateral crura can be combined with a transfixion incision to reduce tip support to allow immediate posterior settling of the tip.

398 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Boxy Tip

A boxy nasal tip is due to either an increased angle of divergence of the medial crura or a wide arc in the dome segment of the lateral crura.. This problem is commonly treated by resection of the cephalic portion of the lateral alar cartilages and interdomal suturing.

Widened Alar Base

A wide alar base is a masculinizing feature. Since most patients seeking rhinoplasty are female, a wide alar base is a commonly encountered problem. The simplest way to narrow a wide alar base is through resection of a portion of the fibrofatty tissue making up the lateral-most portion of the alar rim (e.g., Weir excision). This technique has the disadvantage of placing visible (albeit small and well-hidden) scars on the external nasal skin. Transdomal sutures often used to augment tip projection can also pinch the lateral crura together thus slightly narrowing the alar width.

Wide Nasal Bridge

A wide nasal bridge is also a frequent complaint. This problem can be dealt with directly and indirectly. Clearly, nasal osteotomies will allow medialization of the upper and middle nasal vaults. These osteotomies can be performed via either open or closed approaches, using a continuous or perforated technique. This maneuver is often performed when a prominent dorsal hump has been resected, leaving the dorsal edge of the nose with a widened, open roof, appearance. Preoperatively, the patient’s internal nasal valve angle must be evaluated because in-fracturing will narrow the nasal passage. If the internal nasal valve <12˚, the patient will have obstructed airflow. Dorsal augmentation also gives the appearance of a narrower nose, again highlighting the interplay of the various nasal components.

Complications

Retracted Ala

A retracted ala occurs in patients who have had overresection of the cephalic portions of the lateral crura in an attempt to improve tip definition. As healing progresses, wound contraction rotates the lateral crura cephalically and with it the alar rim. To avoid this pitfall, it is recommended that at least 6-9 mm of lateral crus remain after resection and that one make every attempt to leave as much vestibular mucosa as possible during the procedure. To fix this problem, a free cartilage graft can be used to augment the remaining lateral crura in minor cases. If a severe retraction is encountered, composite grafts from the contralateral ear can be used to provide, lining, coverage and support.

64 Parrot Beak Deformity

A parrot beak deformity refers to excessive supratip fullness following rhinoplasty. This problem can be caused by either underresection of the supratip dorsal hump or overresection of the nasal dorsum. If the cause is the former, further resection to achieve a proper tip-to-supratip proportion is mandated. If the cause is the latter, a dorsal graft is appropriate. When the parrot beak deformity occurs in the early postoperative period it is attributed to edema and wound contraction. In this situation, a trial of conservative management with taping and steroid injection is appropriate. Careful technique with frequent assessments of the appearance of the nose during the procedure is the best way to avoid this problem.

Rhinoplasty |

399 |

Saddle-Nose Deformity |

|

The saddle-nose deformity appears as a disproportionately flattened dorsum, |

|

akin to a boxer’s nose. The most common cause is over-resection of the cartilaginous |

|

septum leaving less than 15 mm of support. Treatment in mild to moderate cases |

|

involves placing additional graft material over the depressed areas to restore the |

|

lateral and frontal profile. In severe cases, cantilevered bone grafts suspended from |

|

the frontal bone may be required. |

|

Open Roof Deformity |

|

An open roof deformity occurs after resection of a dorsal hump without ad- |

|

equate in-fracture of the nasal bones. The dorsal bony edges become visible within a |

|

flattened area of the dorsum. Treatment is intuitive and consists of adequately |

|

in-fracturing the nasal bones. |

|

Inverted-V Deformity |

|

If the mucoperichondrium of the upper lateral cartilages is inadvertently resected, |

|

support to the upper lateral cartilages is lost. This problem causes the upper lateral |

|

cartilages to collapse inferomedially. On frontal view, the caudal edges of the nasal |

|

bones become visible. The best treatment is avoidance, but if it occurs, dorsal carti- |

|

lage grafting to restore dorsal nasal balance is the preferred treatment. |

|

Pearls and Pitfalls |

|

Each case has it own challenges and requires a careful estimation of the deformity |

|

preoperatively, a clear understanding of the techniques available, a proposed plan of |

|

action and sequence, and a meticulous, uncompromising surgical technique. Every |

|

operation has a risk for complication, and only the surgeon who does not operate has |

|

no complications. Under-correction and over-correction of a preexisting deformity |

|

may lead to either persistence of the deformity or the introduction of a new one. A |

|

new deformity may introduce functional deficits. Some deformities are illusory and |

|

correction can only follow accurate diagnosis. For example, when a patient requests |

|

dorsal reduction, first examine the nose in thirds. If the nasal radix is too low, augment |

|

it, don’t reduce the dorsum. The radix augmentation will give the illusion of a smaller |

|

nose. Furthermore, the nose must also be examined in relation to the face. For in- |

|

stance, a nose may appear large because the chin is small; a chin implant may be the |

|

best choice in some cases to achieve the illusion of facial harmony. |

|

Suggested Reading |

|

1. Becker DG. Complications in rhinoplasty. In: Papel I, ed. Facial Plastic and Recon- |

|

structive Surgery. New York: Thieme, 2002:87-96. |

|

2. Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty. In: Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM, eds. Plastic Sur- |

|

gery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:651-669. |

64 |

3. Dingman RO, Natvig P. Surgical anatomy in aesthetic and corrective rhinoplasty. Clin |

|

Plast Surg 1977; 4:111. |

|

4.Guyuron B. Dynamics in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105:2257.

5.Rohrich RJ, Muzaffar AR. Primary rhinoplasty. Plastic Surgery: Indications, Operations and Outcomes V. 2000:2631.

6.Sheen JH, Sheen AP. Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998:1-1440.

7.Sheen JH. Rhinoplasty: Personal evolution and milestones. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105:1820.

8.Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 101:840.

Chapter 65

Genioplasty, Chin and Malar Augmentation

Jeffrey A. Hammoudeh, Christopher Low and Arnulf Baumann

Introduction

The chin provides harmony and character to the face. A strong chin or prominent jaw line is considered to be aesthetically pleasing, especially in males. When chin surgery is indicated, whether by anterior horizontal mandibular osteotomy (AHMO) or by alloplastic implant augmentation, it can create an aesthetically pleasing facial contour and establish proportionate facial height. In addition, the AHMO can improve obstructive sleep apnea by elevating the hyoid bone.

Most genioplasty procedures are done to improve the mandibular profile in order to obtain a more natural profile. Genioplasty can shorten or lengthen the lower third of the face. Facial asymmetry may be corrected by rotation of the chin-point to coincide with the midline. The advantages of osseous genioplasty are versatility, reliability and consistency in correcting problems in the sagittal and vertical planes to achieve greater chin projection.

In order to be able to make an appropriate recommendation, the correct preoperative workup should be performed, including soft and hard tissue analyses. Ideally, cephalometrics and video cephalometric predictions would also be performed.

Anatomy and Analyses

It is important for the surgeon to be familiar with the classic soft tissue analysis and diagram of facial proportions. The size, shape and position of soft and hard tissue can enhance facial harmony and symmetry. The relationship between soft tissue and bone is important for planning the chin correction. For chin advancement, the bone to soft tissue proportion is 1:0.8, meaning that 1 mm of bony change is associated with 0.8 mm of soft tissue change.

The face can be divided into upper, middle and lower thirds. The upper third of the face spans from the hairline to the glabella (G); the middle third from glabella to subnasale (Sn); and the lower third from subnasale to menton (Me). The lower third of the face can be further divided into an upper half (Sn to vermilion of the lower lip) and a lower half (Me to vermilion of the lower lip). The face is “balanced” when the three thirds are of similar height. Cephalometric analysis ensures that skeletal and occlusal disparities are identified and can be corrected before or at the same time as a genioplasty.

Many patients that complain of a small chin truly do not have microgenia. They often have a true deficit of the mandible in the sagittal plane, which can be a class 2 malocclusion (retrognathia) or normo-occlusion (retrogenia). Retrognathia is ideally corrected with a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO); however if the discrepancy is small, advancement genioplasty may sufficiently camouflage the facial profile into an orthognathic appearance. Retrogenia (chin point deficiency

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Genioplasty, Chin and Malar Augmentation |

401 |

in the setting of a class I occlusion) and mild retrognathia (≤3 mm) are ideal cases for a genioplasty. It is important to understand the relationship of the dentition to the chin point. The boney chin point should be about 2 mm posterior to the labial surface of the mandibular incisors. This will help maintain a natural labiomental fold. The position of the labiomental angle is paramount and profoundly influences the aesthetic outcome. Cephalometric analysis helps the surgeon to plan the operative procedure. The treatment plan is based on incorporation of these data into clinical assessment that will facilitate a postsurgical profile that is esthetically pleasing.

Perceived Chin Abnormalities Due to Anomalies of the Maxilla

When facial analysis identifies disharmony within a patient’s profile, the surgeon must determine whether there is an underlying occlusal and skeletal deformity or merely a poorly or over-projected mentum. True maxillomandibular discrepancies should be addressed with orthognathic surgery. In the case where occlusion is stable and a small mandibular deficiency exists (retrogenia), an isolated mandibular sagittal deficiency may be a candidate for an AHMO.

To highlight the importance of the correct diagnosis, one can take the common occurrence of a patient complaining of a “small chin.” A recessed chin may be retrogenia or microgenia. An over projected chin may be macrogenia or prognathia. Micrognathia and macrognathia are rare. Prognathia and retrognathia more commonly contribute to chin point abnormalities. In the setting of a patient complaining of a small chin, the lateral profile should be evaluated. Concavity or convexity in conjunction with the proportions of the middle and lower third of the face should be considered in the planning. The maxilla should be evaluated. If the maxilla is set appropriately in the sagittal plane and there is mild retrognathia (≤3 mm) or retrogenia, then a genioplasty is appropriate. However, if a maxillary developmental dysplasia is present, a formal orthognathic work-up should be done.

In contrast, patients complaining of a “prominent chin” often have pseudomacrogenia. These individuals may have maxillary sagittal hypoplasia, which manifests with a retruded upper lip, a midfacial concavity or deficiency, and a chin that may appear prominent in the sagittal plane. Since the true etiology is maxillary hypoplasia, the corrective procedure would be a Le Fort I osteotomy to advance the maxilla anteriorly to coincide with the chin point. A pitfall would be for a novice surgeon to perform a genioplasty to set the chin point back to coincide with the maxilla.

In maxillary vertical deficiency, the patient presents with pseudomacrogenia due to the counterclockwise rotation of the mandible. In this case, the chin is accentuated and appears larger than normal. Patients with this condition have a short lower third facial height and present with poor maxillary tooth show at rest and when smiling. When the mandible is placed in the normal centric relation, the chin point

increases in the sagittal plane. Maxillary vertical height correction will allow for a 65 more natural position of the chin and only then can a decision be made on the need

for genioplasty.

Maxillary vertical excess may manifest as pseudomicrogenia due to the excessive downward growth of the maxilla causing a clockwise rotation of the mandible. In such cases, the rotation of the mandible results in the appearance of a small chin due to poor projection of the chin in the sagittal plane. The patient will likely have excess gingival show, a long lower third facial height and mentalis