Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

Chapter 62

Otoplasty

Clark F. Schierle and Victor L. Lewis

Introduction

The pinna of the human auricle serves primarily an aesthetic function. This is in contrast to other members of the animal kingdom where active control of the pinna allows for focusing of sound waves for optimal sound localization, providing a distinct survival advantage in certain species. Congenitally prominent ears can be the source of great emotional and psychosocial distress for patients in all stages of life, especially young school age children.

Anatomy and Aesthetics

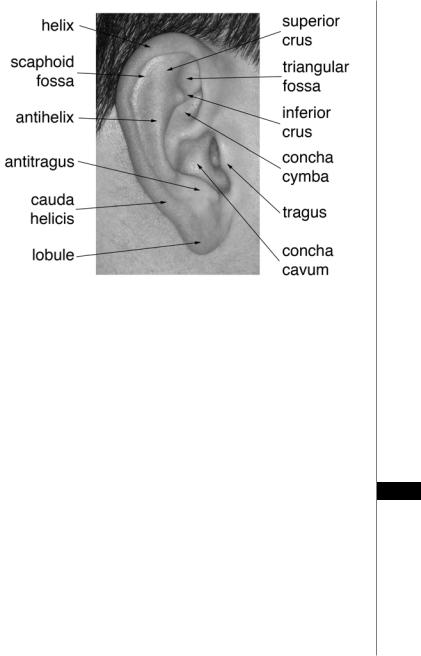

The auricle is a complex fibroelastic cartilage structure which normally measures approximately 6 cm in the vertical axis. The auricle is comprised of several cartilaginous landmarks which serve to make up the normal appearing ear (Fig. 62.1). These can be divided into the various fossae of the auricle and the cartilaginous ridges which separate them. The outermost cartilaginous ridge of the ear is the helical rim. This graceful arch forms the outermost boundary of the auricle and terminates anteriorly in the helical crus. Proceeding centripetally, the next ridge encountered is the antihelix, a fold of cartilage which bifurcates anterosuperiorly into the superior and inferior crura. The fossa between the helix and antihelix is the scaphoid fossa, or scapha. The antihelix defines the border of the conchal bowl, which is divided into the concha cymba superiorly and concha cavum inferiorly by the helical crus. Within the concha cymba the superior and inferior crura of the antihelix define the triangular fossa. Two small cartilaginous protuberances inferiorly form the tragus anteriorly and the antitragus posteriorly at the end of the antihelical rim (the cauda helicis). These are separated by the incisura intertragica. The antitragus and cauda helicis are separated by a small notch known as the fissura antitragohelicina.

The blood supply to the ear derives from the posterior auricular and superficial temporal arteries which supply the posterior and anterior surfaces of the auricle respectively, and are both terminal branches of the external carotid artery. The sensory nerve supply arises anteriorly from the auriculotemporal nerve (branch of CN V3) and posteriorly from the great auricular nerve arising from the cervical plexus, with small contributions to the ear canal from Arnold’s nerve (auricular branch of CN X), Jacobsen’s nerve (tympanic branch of CN IX) and minor fibers of CN VII. Reflecting its more prominent role in focusing sound waves in other species, several rudimentary muscles are variable present in the human auricle. Among these are extrinsic muscles including the superior and posterior auricular muscles which insert on the posterior auricle and triangular fossa respectively, as well as several intrinsic muscles including the major and minor helical, tragal, antitragal, transverse and oblique auricular muscles located on the anterior and

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Otoplasty |

383 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 62.1. Surface anatomy of the human ear.

posterior surfaces of the auricular cartilage. When present, these muscles or structures are supplied by rudimentary branches of the facial nerve (CN VII).

The auricle typically measures between five and six centimeters in vertical dimenstion with a long axis which deviates approximately 20˚ from the vertical when viewed from the side. This parallels the angle of the profile of the nose. The auricle should be about half as wide as it is long with a helix to mastoid distance ranging from 1 cm superiorly to 2 cm inferiorly.

A commonly encountered ear deformity is the congenitally prominent ear, which is characterized by an increase distance from the helical rim to the mastoid scalp. It is often associated with a deep conchal bowl and may lack and antihelical fold altogether. The scaphoconchal angle is increased with flattening of the superior antihelical

crus. The cup ear deformity, also referred to as constricted ear or lop ear involves 62 cosmetically unacceptable overhang of the helix, associated with widening of the concha, flattening of the antihelix, and compression of the scapha an fossa triangu-

laris. Stahl ear, also referred to as “Spock,” “Vulcan,” or Satyr ear, is characterized by the presence of a third antihelical crus, resulting in flattening of the antihelix and angular distortion of the scapha and superior helical rim.

Preoperative Considerations

By the age of five or six years, the pinna has attained 85% of its adult height and otoplasty may be considered. In adults, surgery on the ear can generally be performed under intravenous conscious sedation supplemented with local nerve blockade or local anesthesia alone. Blood thinning medications should be discontinued including careful screening for prescription, over-the-counter and herbal medications.

384 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Preoperative photodocumentation should include standardized frontal, lateral and oblique views with magnified views of any particular areas of interest.

Operative Technique

Due to the complex three dimensional nature of the ear, the ideal technique for otoplasty must be tailored to the particular patient’s deformity and the surgeon’s experience with various techniques. The traditional excision for correction of the prominent ear removes a fusiform ellipse of skin just lateral to the postauricular crease, although some delay committing to both limbs of the ellipse until the end of the procedure after determining precisely how much skin will need to be excised. Anterior incisions may also be employed to provide access to the anterior perichondrial surface. Skin excision alone is generally insufficient to hold an ear in position. Cartilage shaping is achieved through the placement of mattress sutures to reanchor the cartilage, scoring of the cartilage to facilitate reshaping and/or excision of excess cartilage. Sutures are placed in a mattress fashion and go through the full thickness of cartilage and perichondrium and should be fairly wide based (at least 1.5 to 2 cm) to avoid cutting through or creating an antihelix that appears too sharp. Conchoscaphoid mattress sutures (Mustarde sutures) serve to restore the normal conchoscaphoid angle of 90˚ and enhance the antihelical ridge while decreasing projection. Conchomastoid mattress sutures serve to “pin” back the concha. Both these sets of sutures are placed in a radial fashion and tied down gradually until the desired effect is achieved with evenly distributed tension.

The effect is augmented by scoring the anterior surface of the cartilage. Scoring of a cartilaginous or perichondrial surface will generally result in expansion of that surface as an assist in bending of the cartilage away from the side being scored. Patients with excessively prominent conchal bowls may benefit from resection of an ellipse of conchal cartilage. Care and experience allow the proper amount of cartilage to be removed to recreate a graceful fossa without creating an unnatural stepoff in the conchal contour. A mattress suture from the triangular fossa to the temporalis fascia can help correct any residual prominence of the superior pole of the auricle.

Prominent lobules can be addressed by extending the incision inferiorly and closing this portion of the flap in a V-Y manner resulting in reduction of the frontal appearance of the lobule. Alternatively, if the prominence of the lobule is due to an excessively long cauda helicis, simple exision of the excess cartilage and redraping of the skin will improve the deformity.

Finally the skin is redraped, excess skin is excised from the posterior surface of the ear and the wound is closed. Meticulous hemostasis is essential as hematoma

62formation can have disastrous consequences and some authors favor the placement of a small penrose type rubber-band drain to facilitate drainage. A compressive nonadherent dressing is placed and wrapped with a large turban style dressing.

Postoperative Care

In teenagers or adults, otoplasty can easily be performed as an outpatient procedure with a responsible relative or friend available for overnight observation. After the dressing is removed at the first postoperative visit, patients should be instructed to continue to wear lightly supportive tennis or skiing headbands or ear wraps to take tension off of the reconstruction for an additional 6-8 weeks. Hypertrophic scarring or keloid formation can be treated with injection of steroids with or without excision as dictated by the severity of the scar.

Otoplasty |

385 |

Complications

Along with the ubiquitous risks of bleeding and wound infection, the most common sequelae involve an unsatisfactory cosmetic result. Over-correction or, more commonly, under-correction or reversal of the correction with time are the most common complaints. Avoid asymmetry by measuring the helix to mastoid distance. Over-correction of the conchal prominence without addressing superior pole projection and an excessive lobule results in the “telephone ear” deformity. Conversely, over-correction of superior pole and lobule projection with insufficient correction of conchal excess results in the so called “reverse telephone ear.” Failure to anchor conchomastoid sutures in a posterior vector can lead to compromise of the external auditory meatus by occlusion with redundant conchal cartilage. Inadequate hemostasis and failure to recognize a postoperative hematoma can lead to catastrophic loss of the cartilaginous architecture of the auricle, requiring far more complex reconstruction, potentially requiring rib cartilage. Infection should be promptly treated with systemic antibiotic therapy and surgical drainage.

Pearls and Pitfalls

•The biggest disaster is ischemia of the ear. This can lead to cartilage necrosis and a resulting misshapen ear. It can be caused by folding of the ear from too tight a dressing or poor placement of the ear in the dressing due to numbness from anesthesia. Severe postoperative pain is an indication for removal of the dressing and evaluation of the ear.

•Tie the Mustarde mattress sutures first and then look and measure the two ears to achieve as much symmetry as possible. Ears are typically not identical preoperatively.

•Over-correction or an ear that lies flat against the head will not typically improve with time.

•Correction of the antihelix without treating a deep conchal bowl results in an odd deformity requiring revision.

•There are very few occasions when both auricles are seen simultaneously in the course of normal daily activities. Therefore, perfect symmetry from side-to-side is less critical than the correct anatomical harmony of each auricle viewed alone. As an example, this can be very useful when repairing traumatic defects of the ear which require removal of tissue from the helix. The precise size matching of the two auricles is of secondary importance to achieving a balanced, harmonious, natural appearing ear.

Suggested Reading |

62 |

|

1.Kelley P, Hollier L, Stal S. Otoplasty: Evaluation, technique, and review. J Craniofac Surg 2003; 14(5):643.

2.Stenstrom SJ, Heftner J. The Stenstrom otoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 1978; 5(3):465.

3.Dingman RO, Peled I. Corrective cosmetic otoplasty: A simple and accurate technique. Ann Plast Surg 1979; 3(3):250.

4.Elliott Jr RA. Otoplasty: A combined approach. Clin Plast Surg 1990; 17(2):373.

Chapter 63

Blepharoplasty

Robert T. Lancaster, Stephen M. Warren and Elof Eriksson

Introduction

Aesthetic eyelid surgery is intended to brighten and refresh the eyes. By removing baggy skin, an ellipse of muscle and protruding fat, the surgeon has a chance to erase the signs of periorbital aging and endow a youthful appearance. Functional eyelid surgery is largely geared towards correcting congenital or acquired ptosis, ectropion (eversion of the eyelid) and epiblepharon (inversion of eyelashes against globe). While aesthetic and functional eyelid surgery may be nosologically divided, both have a role in every operation.

Eyelid surgery must be preceded by a sound knowledge of the anatomy and a thorough understanding of the deformity to be corrected. Moreover, patient selection may be as important as the technical aspects of resecting/resuspending the periorbital tissues or controlling the lateral canthus. Goals for eyelid surgery include the creation of crisp upper lids, correction of fatty protrusions without hollowing the eyes, reestablishment of lower lid tone, control of the lateral canthus, preservation of aperture length and height, avoidance of scleral show and lagophthalmos, and correction of deep groves, all while maintaining the illusion of symmetry.

Anatomy

The palpebral fissure (aperture of the eye) measures 12-14 mm vertically and 28-30 mm horizontally. The eye is almond-shaped with the lateral canthus slightly more superior than the medial canthus: typical superior elevations at the lateral canthus are 2 mm for men and 4 mm for women. The distance from the lateral canthus to the orbital rim is about 5 mm. The upper lid fold in Caucasians is approximately 8-11 mm. The lower lid crease is about 5-6 mm. The high point of the brow is superior to the lateral limbus. The upper lid rests 2 mm below the superior limbus of the iris and the lower eyelid rests at the inferior limbus.

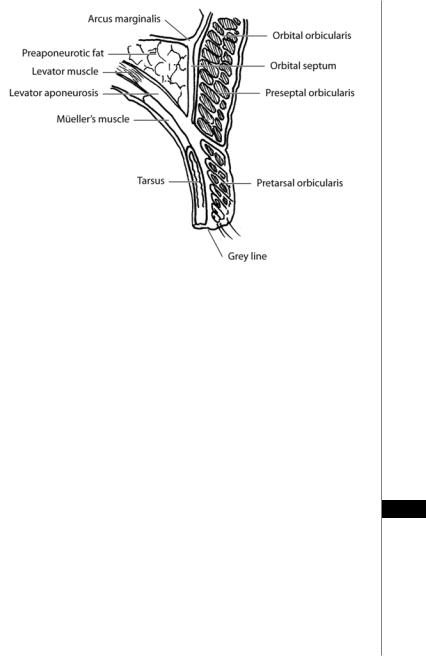

Upper Eyelids

The skin of the eyelid is less than 1 mm thick. With aging and loss of elasticity, wrinkling and sagging of the eyelid occurs. Beneath the skin and subcutaneous tissues lies the orbicularis oculi muscle, which is divided into an outer orbital portion and an inner palpebral portion (Fig. 63.1). The palpebral portion is further subdivided into preseptal and pretarsal parts. Collectively, the orbicularis oculi closes the eye, shortens and milks the canniliculi, and expands the lacrimal sac. Beneath the orbital and preseptal portions of the orbicularis oculi is the preseptal fat, known as the retroorbicularis oculi fat (ROOF). This fat pad lies over the orbital rim extending outward toward the tail of eyebrow. Resecting the ROOF decreases the heaviness of the lateral brow and upper lid, but the ROOF isn’t the primary culprit in

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Blepharoplasty |

387 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 63.1. Upper eyelid anatomy.

baggy upper lids. The orbital septum lies deep to the orbicularis. It hangs from the superior orbital rim and joins the levator aponeurosis at the superior border of the tarsal plate. Weakening of the septum with aging, hereditary predisposition, or trauma may cause protrusion of the orbital fat. The upper lid contains two fat pads: medial and central (the lateral space is occupied by the lacrimal gland). The medial and central compartments are separated by the superior oblique muscle. The medial fat pad is lighter in color (similar to butterscotch), firmer in consistency, and usually requires more local anesthesia during resection than the central compartment. The medial compartment also contains the terminal branch of the ophthalmic artery; we find that attending surgeons will take an extra second to ensure that this vessel is satisfactorily coagulated during fat resection.

The upper lid tarsus is a fibrous plate that is approximately 10 mm wide in the central upper lid, narrowing medially and laterally. The tarsal plates extend from the lateral commissure to the punctum, and it contains numerous meibomian glands that empty into the ciliary border. There are two muscles responsible for opening the upper 63 eyelids: the levator muscle (primary lid elevator) and Müller’s muscle. The levator muscle originates at the apex of the orbit, just superior to the superior rectus. At the orbital aperture, it is supported by Whitnall’s ligament, which functions to translate

the horizontal force of this muscle into the posterior and vertical motion necessary for lid elevation. The levator muscle becomes aponeurotic as it passes Whitnall’s ligament. The anterior interdigitation of the aponeurosis with the orbicularis muscle fibers leads to the formation of the supratarsal fold. Müller’s muscle originates from the posterior aspect of the levator aponeurosis and travels inferiorly, closely adherent to the conjunctiva, to insert on the superior border of the tarsus. Müller’s muscle is sympathetically innervated. The conjunctiva is the inner most layer of the upper lid.

388 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Lower Eyelids

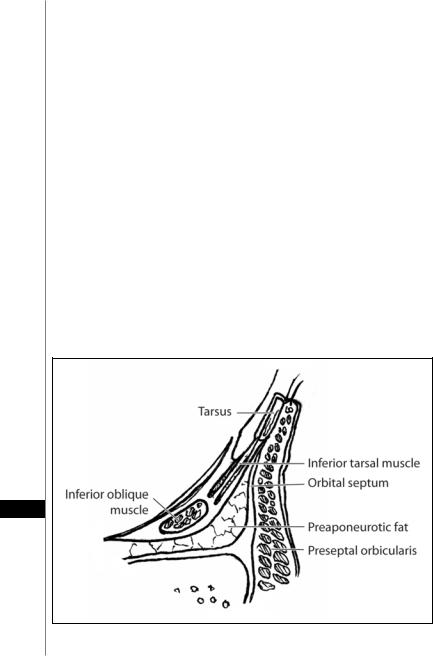

The lower eyelid is often described as being composed of three lamellae (Fig. 63.2). The anterior lamella consists of the skin, orbicularis oculi (orbital, preseptal and pretarsal) muscle, and preseptal suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF). The middle lamella is the orbital septum. The septum is a continuation of the orbital periostium that extends from the inferior orbital rim (arcus marginalis) to the inferior border of the tarsus. It provides the anterior border of the medial, middle and lateral fat compartments. Although these compartments are more imaginative than anatomic, the inferior oblique (most commonly injured during blepharoplasty) separates the medial and middle compartments; the arcuate expanse divides the middle from the lateral fat pad. The medial fat pad tends to be whiter than the middle and lateral pads.

The posterior lamella is composed of the tarsus, lower lid retractors and the conjunctiva. The lower lid tarsal plate is only about 4.5 mm wide at the mid-pupil. The lower eyelid retractor system originates as a fascial extension of the inferior rectus muscle (capsulopalpebral head). This fascial system splits to encapsulate the inferior oblique muscle and then reunites to form a dense fibrous sheet (capsulopalpebral fascia) that inserts onto the inferior tarsal border. The inferior tarsal muscle is the smooth muscle analog of the upper lid Müller’s muscle. The inferior tarsal muscle originates in the inferior fornical area and extends toward the inferior tarsal border but does not insert on the tarsal border as does its counterpart in the upper eyelid. The inferior tarsal muscle provides sympathetic innervation to the lower eyelid, and interruption of its innervation results in a slightly elevated position of the lower eyelid margin, as observed in Horner syndrome. Otherwise, the inferior tarsal muscle has little pathologic significance.

63

Figure 63.2. Lower eyelid anatomy.

Blepharoplasty |

389 |

Asian Eyelids

There are a number of anatomic differences between Asian and Caucasian eyelids. In the Asian upper eyelids, the skin and subcutaneous fat tend to be thicker. The ROOF is heavier. The orbital septum is weaker and thinner and it tends to drape below the upper border of the tarsal plate. The levator aponeurotic dermal extensions are weak or nonexistent. The paucity of levator-dermal extensions is responsible of the low-lying or absent supratarsal fold. Epicanthal folds cover the medial angle and lacrimal caruncle. Trichiasis is caused by the overhanging upper eyelid skin pushing down on the eyelashes. Collectively, these features give the Asian eyelid more fullness, a lower lid crease and a narrower palpebral fissure.

Canthal Tendons

Medially, the superficial heads of the upper and lower pretarsal muscles join to form the medial canthal tendon (Fig. 63.3). This tendon is firmly attached to the anterior lacrimal crest. The superficial heads of the preseptal muscles attach to the medial canthal tendon. The deep heads of the preseptal and pretarsal muscles attach to the posterior lacrimal crest, just behind the lacrimal sac. Laterally, the upper and lower pretarsal muscles join to form the lateral canthal tendon, which inserts just posterior to the orbital tubercle. The upper and lower preseptal muscles join laterally to form the lateral palpebral raphe, which is attached to the skin.

Preoperative Considerations

During the complete medical history, one should inquire about a history of diabetes, hypertension, coagulopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, renal disease, cardiopulmonary disease or glaucoma; each of these diseases can have a role in eye symptomatology and effect postoperative recovery. Patients with a history of collagen vascular diseases, such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematous, periarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, rosacea, rheumatoid arthritis, or secondary Sjögren syndrome have a higher risk of postoperative dry eye syndrome. Finally, elicit an ophthalmologic history. This includes previous eyelid surgery, eyelid trauma, eyelid infection, eyelid allergy, eyelid swelling, the use of glasses or contact lenses, and changes in visual fields and/or visual acuity.

The physical examination first includes looking at the full face. Note facial appearance, asymmetry and wrinkles. Examine the periorbital area for crow’s feet, fine wrinkles (at rest and with smiling), and the appearance of the globes, infraorbital

63

Figure 63.3. Canthal tendons.

390 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

rims, cheeks and malar bags. Assess for negative vector (in the lateral view: anterior most projection of the globe, the lower eyelid margin and the malar eminence). A negative vector is one which angles posteriorly and indicates an absence of support for the lower lid). Patients with a negative vector are at higher risk for postoperative dryness. Note any pseudoherniated orbital fat and hypertrophied orbicularis muscle. Pressure on the upper eyelid and globe causes pseudoherniated orbital fat in the lower eyelid to be more evident. Having the patient look upward can help to delineate the lower eyelid fat pockets. Examine the eyelids for discoloration, hypertrophied skin and skin lesions. Excessive skin produces a crepe-like quality in the lower eyelid skin. Also, note the position of the lacrimal gland, in particular whether or not it has fallen from the lacrimal fossa. Assess for Bell’s phenomenon. The Schirmer’s I test may be performed by placing a 5 x 35 mm strip of #41 filter paper between the lower lateral lid and globe for 5 minutes. This test measures both basic and reflexive tear production. Less than 10 mm of moisture on the paper suggests that the patient may be at risk for postoperative dry eyes. The Schirmer’s II test measures only basic tear secretion by blocking reflex secretion with a topical anesthetic. The snapback test is performed by grasping the lower eyelid skin and pulling the lid away from the globe. The rapidity with which the lid snaps back against the globe gives an estimate of the probability of postoperative ectropion.

Surgical Technique

Upper Blepheroplasty

Begin the procedure by marking the lower border of the skin resection with the patient in the upright position. This curvilinear line is usually located 10 mm above the lid margin in the natural eyelid crease. The upper border of the skin resection is usually estimated by a pinch test; there should be 15-18 mm of skin between the upper border of the skin resection and the eyebrow. Infiltrate local anesthetic evenly throughout the upper eyelid. Excise the skin and achieve hemostasis with pinpoint electrocautery. Resect a sliver of orbicularis oculi muscle to reveal the preaponeurotic fat. The preaponeurotic fat is resected as desired, and the orbital septum is opened in defined points at the medial and central fat pads or along its length. Excess orbital fat is estimated by applying gentle pressure to the globe. This excess fat is resected with care taken to ensure hemostasis. The skin then is reapproximated, and the procedure is complete.

Lower Lid Blepharoplasty, Subciliary

At the start of the subciliary blepharoplasty approach, a Frost suture can be placed

63in the gray line lateral or medial to the limbus to facilitate retraction and protect the globe. Alternatively, a lubricated corneal shield may be inserted. An incision is made just lateral to the lower lid margin. A scissors is used to develop a subcutaneous plane across the subciliary margin and complete the skin incision. Care is taken to protect the lashes. A skin-only or skin-muscle flap can be created to gain access to the orbital fat. If a skin-only flap has been elevated, the orbicularis is opened by incisions over the medial, central and lateral compartments. If a skin-muscle flap is chosen, all three fat compartments are in plain view. The inferior oblique muscle is identified between the medial and middle fat pads, and it is protected easily. The lateral compartment is slightly higher than the middle and should be identified carefully because it is the most common compartment to be overlooked. After resecting the orbital fat, a conservative skin excision is performed and the skin is closed.

Blepharoplasty |

391 |

Lower Lid Blepharoplasty, Transconjunctival |

|

Two approaches to transconjunctival blepharoplasty are used: retroseptal and |

|

preseptal. The retroseptal approach is taken by incising from the caruncle to the |

|

lateral canthal area at a level half way between the inferior margin of the tarsal |

|

plate and the fornix. A traction stitch can be placed through the upper conjunc- |

|

tiva. The orbital fat pads can be assessed and excess fat resected to the level of |

|

the orbital rim. Once the fat is resected, some surgeons will close the |

|

transconjuctival incision with absorbable sutures, but most will realign the inci- |

|

sion without suturing. |

|

In the preseptal approach, the incision is made through the conjunctiva below |

|

the tarsus, and a dissection plane is developed between the orbicularis muscle and |

|

the orbital septum. The orbicularis is opened by incisions over the medial, central, |

|

and lateral compartments, and the fat is resected. Closure is the same as above. |

|

Lateral Canthopexy |

|

There are many techniques to suspend the lateral border of the lower tarsal plate. |

|

Classically, the lateral canthus is sutured to Whitnall’s tubercle, which is located |

|

about 1 cm inside the lateral orbital rim. The purpose of any type of lateral tarsal |

|

suspension is to simply tighten the lower lid, improve its coaptation against the |

|

globe, and reduce the incidence of postoperative ectropion. |

|

Kunt-Simonowsky Procedure |

|

A small composite wedge resection of the lateral lower lid is an alternative to |

|

lateral suspension procedures. This procedure is designed to take up slack in the |

|

lower lid and improve lid position. However, some surgeons argue that wedge resec- |

|

tion shortens the aperture of the eye and causes a rounding of the lateral palpebral |

|

fissure. |

|

Postoperative Care |

|

The patient should stay in an observational area after surgery for at least 1-2 |

|

hours. Ice water-soaked gauze compresses should be applied continuously for 24-48 |

|

hours to decrease swelling, as well as to reduce postoperative pain. Additionally, the |

|

patient’s head should be elevated greater than 45˚ to decrease edema and the collec- |

|

tion of sanguinous fluid. Ocular lubrication with artificial tears should be prescribed, |

|

particularly if the patient has a preexisting history of dry eyes or if postoperative |

|

lagophthalmus is present. The patient should avoid any strenuous activity. Stitches |

|

are removed in clinic in 3-7 days. |

|

Complications |

63 |

Retrobulbar Hematoma |

|

The most concerning postoperative complication is a retrobulbar hematoma |

|

(bleeding posterior to the orbital septum). The incidence is about 0.04%. This |

|

complication is more likely to occur in hypertensive patients with intraoperative |

|

hypertension. Thus, adequate pain control during the procedure becomes equally |

|

as important as precise cauterization of vessels. Significant retrobulbar hemorrhage |

|

will lead to visible protrusion of the globe initially and then to a rapid increase in |

|

intraocular pressure to greater than 30 mm Hg (normal = 10-20 mm Hg). As the |

|

intraocular pressure approaches diastolic levels, the risk of total vision loss increases |

|