- •Preface

- •Approach and Pedagogy

- •Chapter 1

- •Introducing Psychology

- •1.1 Psychology as a Science

- •The Problem of Intuition

- •Research Focus: Unconscious Preferences for the Letters of Our Own Name

- •Why Psychologists Rely on Empirical Methods

- •Levels of Explanation in Psychology

- •The Challenges of Studying Psychology

- •1.2 The Evolution of Psychology: History, Approaches, and Questions

- •Early Psychologists

- •Structuralism: Introspection and the Awareness of Subjective Experience

- •Functionalism and Evolutionary Psychology

- •Psychodynamic Psychology

- •Behaviorism and the Question of Free Will

- •Research Focus: Do We Have Free Will?

- •The Cognitive Approach and Cognitive Neuroscience

- •The War of the Ghosts

- •Social-Cultural Psychology

- •The Many Disciplines of Psychology

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: How to Effectively Learn and Remember

- •1.3 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 2

- •Psychological Science

- •Psychological Journals

- •2.1 Psychologists Use the Scientific Method to Guide Their Research

- •The Scientific Method

- •Laws and Theories as Organizing Principles

- •The Research Hypothesis

- •Conducting Ethical Research

- •Characteristics of an Ethical Research Project Using Human Participants

- •Ensuring That Research Is Ethical

- •Research With Animals

- •APA Guidelines on Humane Care and Use of Animals in Research

- •Descriptive Research: Assessing the Current State of Affairs

- •Correlational Research: Seeking Relationships Among Variables

- •Experimental Research: Understanding the Causes of Behavior

- •Research Focus: Video Games and Aggression

- •2.3 You Can Be an Informed Consumer of Psychological Research

- •Threats to the Validity of Research

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Critically Evaluating the Validity of Websites

- •2.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 3

- •Brains, Bodies, and Behavior

- •Did a Neurological Disorder Cause a Musician to Compose Boléro and an Artist to Paint It 66 Years Later?

- •3.1 The Neuron Is the Building Block of the Nervous System

- •Neurons Communicate Using Electricity and Chemicals

- •Video Clip: The Electrochemical Action of the Neuron

- •Neurotransmitters: The Body’s Chemical Messengers

- •3.2 Our Brains Control Our Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior

- •The Old Brain: Wired for Survival

- •The Cerebral Cortex Creates Consciousness and Thinking

- •Functions of the Cortex

- •The Brain Is Flexible: Neuroplasticity

- •Research Focus: Identifying the Unique Functions of the Left and Right Hemispheres Using Split-Brain Patients

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Why Are Some People Left-Handed?

- •3.3 Psychologists Study the Brain Using Many Different Methods

- •Lesions Provide a Picture of What Is Missing

- •Recording Electrical Activity in the Brain

- •Peeking Inside the Brain: Neuroimaging

- •Research Focus: Cyberostracism

- •3.4 Putting It All Together: The Nervous System and the Endocrine System

- •Electrical Control of Behavior: The Nervous System

- •The Body’s Chemicals Help Control Behavior: The Endocrine System

- •3.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 4

- •Sensing and Perceiving

- •Misperception by Those Trained to Accurately Perceive a Threat

- •4.1 We Experience Our World Through Sensation

- •Sensory Thresholds: What Can We Experience?

- •Link

- •Measuring Sensation

- •Research Focus: Influence without Awareness

- •4.2 Seeing

- •The Sensing Eye and the Perceiving Visual Cortex

- •Perceiving Color

- •Perceiving Form

- •Perceiving Depth

- •Perceiving Motion

- •Beta Effect and Phi Phenomenon

- •4.3 Hearing

- •Hearing Loss

- •4.4 Tasting, Smelling, and Touching

- •Tasting

- •Smelling

- •Touching

- •Experiencing Pain

- •4.5 Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Perception

- •How the Perceptual System Interprets the Environment

- •Video Clip: The McGurk Effect

- •Video Clip: Selective Attention

- •Illusions

- •The Important Role of Expectations in Perception

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: How Understanding Sensation and Perception Can Save Lives

- •4.6 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 5

- •States of Consciousness

- •An Unconscious Killing

- •5.1 Sleeping and Dreaming Revitalize Us for Action

- •Research Focus: Circadian Rhythms Influence the Use of Stereotypes in Social Judgments

- •Sleep Stages: Moving Through the Night

- •Sleep Disorders: Problems in Sleeping

- •The Heavy Costs of Not Sleeping

- •Dreams and Dreaming

- •5.2 Altering Consciousness With Psychoactive Drugs

- •Speeding Up the Brain With Stimulants: Caffeine, Nicotine, Cocaine, and Amphetamines

- •Slowing Down the Brain With Depressants: Alcohol, Barbiturates and Benzodiazepines, and Toxic Inhalants

- •Opioids: Opium, Morphine, Heroin, and Codeine

- •Hallucinogens: Cannabis, Mescaline, and LSD

- •Why We Use Psychoactive Drugs

- •Research Focus: Risk Tolerance Predicts Cigarette Use

- •5.3 Altering Consciousness Without Drugs

- •Changing Behavior Through Suggestion: The Power of Hypnosis

- •Reducing Sensation to Alter Consciousness: Sensory Deprivation

- •Meditation

- •Video Clip: Try Meditation

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: The Need to Escape Everyday Consciousness

- •5.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 6

- •Growing and Developing

- •The Repository for Germinal Choice

- •6.1 Conception and Prenatal Development

- •The Zygote

- •The Embryo

- •The Fetus

- •How the Environment Can Affect the Vulnerable Fetus

- •6.2 Infancy and Childhood: Exploring and Learning

- •The Newborn Arrives With Many Behaviors Intact

- •Research Focus: Using the Habituation Technique to Study What Infants Know

- •Cognitive Development During Childhood

- •Video Clip: Object Permanence

- •Social Development During Childhood

- •Knowing the Self: The Development of the Self-Concept

- •Video Clip: The Harlows’ Monkeys

- •Video Clip: The Strange Situation

- •Research Focus: Using a Longitudinal Research Design to Assess the Stability of Attachment

- •6.3 Adolescence: Developing Independence and Identity

- •Physical Changes in Adolescence

- •Cognitive Development in Adolescence

- •Social Development in Adolescence

- •Developing Moral Reasoning: Kohlberg’s Theory

- •Video Clip: People Being Interviewed About Kohlberg’s Stages

- •6.4 Early and Middle Adulthood: Building Effective Lives

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: What Makes a Good Parent?

- •Physical and Cognitive Changes in Early and Middle Adulthood

- •Menopause

- •Social Changes in Early and Middle Adulthood

- •6.5 Late Adulthood: Aging, Retiring, and Bereavement

- •Cognitive Changes During Aging

- •Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

- •Social Changes During Aging: Retiring Effectively

- •Death, Dying, and Bereavement

- •6.6 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 7

- •Learning

- •My Story of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- •7.1 Learning by Association: Classical Conditioning

- •Pavlov Demonstrates Conditioning in Dogs

- •The Persistence and Extinction of Conditioning

- •The Role of Nature in Classical Conditioning

- •How Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior: The Research of Thorndike and Skinner

- •Video Clip: Thorndike’s Puzzle Box

- •Creating Complex Behaviors Through Operant Conditioning

- •7.3 Learning by Insight and Observation

- •Observational Learning: Learning by Watching

- •Video Clip: Bandura Discussing Clips From His Modeling Studies

- •Research Focus: The Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggression

- •7.4 Using the Principles of Learning to Understand Everyday Behavior

- •Using Classical Conditioning in Advertising

- •Video Clip: Television Ads

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Operant Conditioning in the Classroom

- •Reinforcement in Social Dilemmas

- •7.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 8

- •Remembering and Judging

- •She Was Certain, but She Was Wrong

- •Differences between Brains and Computers

- •Video Clip: Kim Peek

- •8.1 Memories as Types and Stages

- •Explicit Memory

- •Implicit Memory

- •Research Focus: Priming Outside Awareness Influences Behavior

- •Stages of Memory: Sensory, Short-Term, and Long-Term Memory

- •Sensory Memory

- •Short-Term Memory

- •8.2 How We Remember: Cues to Improving Memory

- •Encoding and Storage: How Our Perceptions Become Memories

- •Research Focus: Elaboration and Memory

- •Using the Contributions of Hermann Ebbinghaus to Improve Your Memory

- •Retrieval

- •Retrieval Demonstration

- •States and Capital Cities

- •The Structure of LTM: Categories, Prototypes, and Schemas

- •The Biology of Memory

- •8.3 Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory and Cognition

- •Source Monitoring: Did It Really Happen?

- •Schematic Processing: Distortions Based on Expectations

- •Misinformation Effects: How Information That Comes Later Can Distort Memory

- •Overconfidence

- •Heuristic Processing: Availability and Representativeness

- •Salience and Cognitive Accessibility

- •Counterfactual Thinking

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Cognitive Biases in the Real World

- •8.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 9

- •Intelligence and Language

- •How We Talk (or Do Not Talk) about Intelligence

- •9.1 Defining and Measuring Intelligence

- •General (g) Versus Specific (s) Intelligences

- •Measuring Intelligence: Standardization and the Intelligence Quotient

- •The Biology of Intelligence

- •Is Intelligence Nature or Nurture?

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Emotional Intelligence

- •9.2 The Social, Cultural, and Political Aspects of Intelligence

- •Extremes of Intelligence: Retardation and Giftedness

- •Extremely Low Intelligence

- •Extremely High Intelligence

- •Sex Differences in Intelligence

- •Racial Differences in Intelligence

- •Research Focus: Stereotype Threat

- •9.3 Communicating With Others: The Development and Use of Language

- •The Components of Language

- •Examples in Which Syntax Is Correct but the Interpretation Can Be Ambiguous

- •The Biology and Development of Language

- •Research Focus: When Can We Best Learn Language? Testing the Critical Period Hypothesis

- •Learning Language

- •How Children Learn Language: Theories of Language Acquisition

- •Bilingualism and Cognitive Development

- •Can Animals Learn Language?

- •Video Clip: Language Recognition in Bonobos

- •Language and Perception

- •9.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 10

- •Emotions and Motivations

- •Captain Sullenberger Conquers His Emotions

- •10.1 The Experience of Emotion

- •Video Clip: The Basic Emotions

- •The Cannon-Bard and James-Lange Theories of Emotion

- •Research Focus: Misattributing Arousal

- •Communicating Emotion

- •10.2 Stress: The Unseen Killer

- •The Negative Effects of Stress

- •Stressors in Our Everyday Lives

- •Responses to Stress

- •Managing Stress

- •Emotion Regulation

- •Research Focus: Emotion Regulation Takes Effort

- •10.3 Positive Emotions: The Power of Happiness

- •Finding Happiness Through Our Connections With Others

- •What Makes Us Happy?

- •10.4 Two Fundamental Human Motivations: Eating and Mating

- •Eating: Healthy Choices Make Healthy Lives

- •Obesity

- •Sex: The Most Important Human Behavior

- •The Experience of Sex

- •The Many Varieties of Sexual Behavior

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Regulating Emotions to Improve Our Health

- •10.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 11

- •Personality

- •Identical Twins Reunited after 35 Years

- •11.1 Personality and Behavior: Approaches and Measurement

- •Personality as Traits

- •Example of a Trait Measure

- •Situational Influences on Personality

- •The MMPI and Projective Tests

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Leaders and Leadership

- •11.2 The Origins of Personality

- •Psychodynamic Theories of Personality: The Role of the Unconscious

- •Id, Ego, and Superego

- •Research Focus: How the Fear of Death Causes Aggressive Behavior

- •Strengths and Limitations of Freudian and Neo-Freudian Approaches

- •Focusing on the Self: Humanism and Self-Actualization

- •Research Focus: Self-Discrepancies, Anxiety, and Depression

- •Studying Personality Using Behavioral Genetics

- •Studying Personality Using Molecular Genetics

- •Reviewing the Literature: Is Our Genetics Our Destiny?

- •11.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 12

- •Defining Psychological Disorders

- •When Minor Body Imperfections Lead to Suicide

- •12.1 Psychological Disorder: What Makes a Behavior “Abnormal”?

- •Defining Disorder

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Combating the Stigma of Abnormal Behavior

- •Diagnosing Disorder: The DSM

- •Diagnosis or Overdiagnosis? ADHD, Autistic Disorder, and Asperger’s Disorder

- •Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- •Autistic Disorder and Asperger’s Disorder

- •12.2 Anxiety and Dissociative Disorders: Fearing the World Around Us

- •Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- •Panic Disorder

- •Phobias

- •Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

- •Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- •Dissociative Disorders: Losing the Self to Avoid Anxiety

- •Dissociative Amnesia and Fugue

- •Dissociative Identity Disorder

- •Explaining Anxiety and Dissociation Disorders

- •12.3 Mood Disorders: Emotions as Illness

- •Behaviors Associated with Depression

- •Dysthymia and Major Depressive Disorder

- •Bipolar Disorder

- •Explaining Mood Disorders

- •Research Focus: Using Molecular Genetics to Unravel the Causes of Depression

- •12.4 Schizophrenia: The Edge of Reality and Consciousness

- •Symptoms of Schizophrenia

- •Explaining Schizophrenia

- •12.5 Personality Disorders

- •Borderline Personality Disorder

- •Research Focus: Affective and Cognitive Deficits in BPD

- •Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD)

- •12.6 Somatoform, Factitious, and Sexual Disorders

- •Somatoform and Factitious Disorders

- •Sexual Disorders

- •Disorders of Sexual Function

- •Paraphilias

- •12.7 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 13

- •Treating Psychological Disorders

- •Therapy on Four Legs

- •13.1 Reducing Disorder by Confronting It: Psychotherapy

- •DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Diagnosing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Seeking Treatment for Psychological Difficulties

- •Psychodynamic Therapy

- •Important Characteristics and Experiences in Psychoanalysis

- •Humanistic Therapies

- •Behavioral Aspects of CBT

- •Cognitive Aspects of CBT

- •Combination (Eclectic) Approaches to Therapy

- •13.2 Reducing Disorder Biologically: Drug and Brain Therapy

- •Drug Therapies

- •Using Stimulants to Treat ADHD

- •Antidepressant Medications

- •Antianxiety Medications

- •Antipsychotic Medications

- •Direct Brain Intervention Therapies

- •13.3 Reducing Disorder by Changing the Social Situation

- •Group, Couples, and Family Therapy

- •Self-Help Groups

- •Community Mental Health: Service and Prevention

- •Some Risk Factors for Psychological Disorders

- •Research Focus: The Implicit Association Test as a Behavioral Marker for Suicide

- •13.4 Evaluating Treatment and Prevention: What Works?

- •Effectiveness of Psychological Therapy

- •Research Focus: Meta-Analyzing Clinical Outcomes

- •Effectiveness of Biomedical Therapies

- •Effectiveness of Social-Community Approaches

- •13.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 14

- •Psychology in Our Social Lives

- •Binge Drinking and the Death of a Homecoming Queen

- •14.1 Social Cognition: Making Sense of Ourselvesand Others

- •Perceiving Others

- •Forming Judgments on the Basis of Appearance: Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- •Implicit Association Test

- •Research Focus: Forming Judgments of People in Seconds

- •Close Relationships

- •Causal Attribution: Forming Judgments by Observing Behavior

- •Attitudes and Behavior

- •14.2 Interacting With Others: Helping, Hurting, and Conforming

- •Helping Others: Altruism Helps Create Harmonious Relationships

- •Why Are We Altruistic?

- •How the Presence of Others Can Reduce Helping

- •Video Clip: The Case of Kitty Genovese

- •Human Aggression: An Adaptive yet Potentially Damaging Behavior

- •The Ability to Aggress Is Part of Human Nature

- •Negative Experiences Increase Aggression

- •Viewing Violent Media Increases Aggression

- •Video Clip

- •Research Focus: The Culture of Honor

- •Conformity and Obedience: How Social Influence Creates Social Norms

- •Video Clip

- •Do We Always Conform?

- •14.3 Working With Others: The Costs and Benefits of Social Groups

- •Working in Front of Others: Social Facilitation and Social Inhibition

- •Working Together in Groups

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Do Juries Make Good Decisions?

- •Using Groups Effectively

- •14.4 Chapter Summary

Table 2.2 Characteristics of the Three Research Designs

Research |

|

|

|

design |

Goal |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Provides a relatively complete picture |

Does not assess relationships |

|

|

of what is occurring at a given time. |

among variables. May be |

|

To create a snapshot of the |

Allows the development of questions |

unethical if participants do not |

Descriptive |

current state of affairs |

for further study. |

know they are being observed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Allows testing of expected |

|

|

|

relationships between and among |

Cannot be used to draw |

|

To assess the relationships |

variables and the making of |

inferences about the causal |

|

between and among two or |

predictions. Can assess these |

relationships between and among |

Correlational |

more variables |

relationships in everyday life events. |

the variables. |

|

|

|

|

|

To assess the causal impact |

|

Cannot experimentally |

|

of one or more experimental |

Allows drawing of conclusions about |

manipulate many important |

|

manipulations on a |

the causal relationships among |

variables. May be expensive and |

Experimental |

dependent variable |

variables. |

time consuming. |

|

|

|

|

There are three major research designs used by psychologists, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Source: Stangor, C. (2011). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). Mountain View, CA: Cengage.

Descriptive Research: Assessing the Current State of Affairs

Descriptive research is designed to create a snapshot of the current thoughts, feelings, or behavior of individuals. This section reviews three types of descriptive research: case studies, surveys, and naturalistic observation.

Sometimes the data in a descriptive research project are based on only a small set of individuals, often only one person or a single small group. These research designs are known

as case studies—descriptive records of one or more individual’s experiences and behavior. Sometimes case studies involve ordinary individuals, as when developmental psychologist Jean Piaget used his observation of his own children to develop his stage theory of cognitive development. More frequently, case studies are conducted on individuals who have unusual or abnormal experiences or characteristics or who find themselves in particularly difficult or

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

62 |

stressful situations. The assumption is that by carefully studying individuals who are socially marginal, who are experiencing unusual situations, or who are going through a difficult phase in their lives, we can learn something about human nature.

Sigmund Freud was a master of using the psychological difficulties of individuals to draw conclusions about basic psychological processes. Freud wrote case studies of some of his most interesting patients and used these careful examinations to develop his important theories of personality. One classic example is Freud’s description of “Little Hans,” a child whose fear of horses the psychoanalyst interpreted in terms of repressed sexual impulses and the Oedipus complex (Freud (1909/1964). [1]

Another well-known case study is Phineas Gage, a man whose thoughts and emotions were extensively studied by cognitive psychologists after a railroad spike was blasted through his skull in an accident. Although there is question about the interpretation of this case study (Kotowicz, 2007), [2] it did provide early evidence that the brain’s frontal lobe is involved in emotion and

morality (Damasio et al., 2005). [3] An interesting example of a case study in clinical psychology

is described by Rokeach (1964),[4] who investigated in detail the beliefs and interactions among three patients with schizophrenia, all of whom were convinced they were Jesus Christ.

In other cases the data from descriptive research projects come in the form of a survey—a measure administered through either an interview or a written questionnaire to get a picture of the beliefs or behaviors of a sample of people of interest. The people chosen to participate in the research (known as the sample) are selected to be representative of all the people that the researcher wishes to know about (the population). In election polls, for instance, a sample is taken from the population of all “likely voters” in the upcoming elections.

The results of surveys may sometimes be rather mundane, such as “Nine out of ten doctors prefer Tymenocin,” or “The median income in Montgomery County is $36,712.” Yet other times (particularly in discussions of social behavior), the results can be shocking: “More than 40,000 people are killed by gunfire in the United States every year,” or “More than 60% of women between the ages of 50 and 60 suffer from depression.” Descriptive research is frequently used by psychologists to get an estimate of the prevalence (or incidence) of psychological disorders.

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

63 |

A final type of descriptive research—known as naturalistic observation—is research based on the observation of everyday events. For instance, a developmental psychologist who watches children on a playground and describes what they say to each other while they play is conducting descriptive research, as is a biopsychologist who observes animals in their natural habitats. One example of observational research involves a systematic procedure known as the strange situation, used to get a picture of how adults and young children interact. The data that are collected in the strange situation are systematically coded in a coding sheet such as that shown in Table 2.3 "Sample Coding Form Used to Assess Child’s and Mother’s Behavior in the Strange Situation".

Table 2.3 Sample Coding Form Used to Assess Child’s and Mother’s Behavior in the Strange Situation

Coder name: Olive

|

Coding categories |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Episode |

Proximity |

Contact |

Resistance |

Avoidance |

|

|

|

|

|

Mother and baby play alone |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mother puts baby down |

4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Stranger enters room |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mother leaves room; stranger plays with |

|

|

|

|

baby |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mother reenters, greets and may comfort |

|

|

|

|

baby, then leaves again |

4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Stranger tries to play with baby |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mother reenters and picks up baby |

6 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Coding categories explained

Proximity |

The baby moves toward, grasps, or climbs on the adult. |

|

|

|

The baby resists being put down by the adult by crying or trying to climb |

Maintaining contact |

back up. |

|

|

Resistance |

The baby pushes, hits, or squirms to be put down from the adult’s arms. |

|

|

Avoidance |

The baby turns away or moves away from the adult. |

|

|

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

64 |

Coder name: Olive

This table represents a sample coding sheet from an episode of the “strange situation,” in which an infant (usually about 1 year old) is observed playing in a room with two adults—the child’s mother and a stranger. Each of the four coding categories is scored by the coder from 1 (the baby makes no effort to engage in the behavior) to 7 (the baby makes a significant effort to engage in the behavior). More information about the meaning of the coding can be found in Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall (1978). [5]

Source: Stangor, C. (2011). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). Mountain View, CA: Cengage.

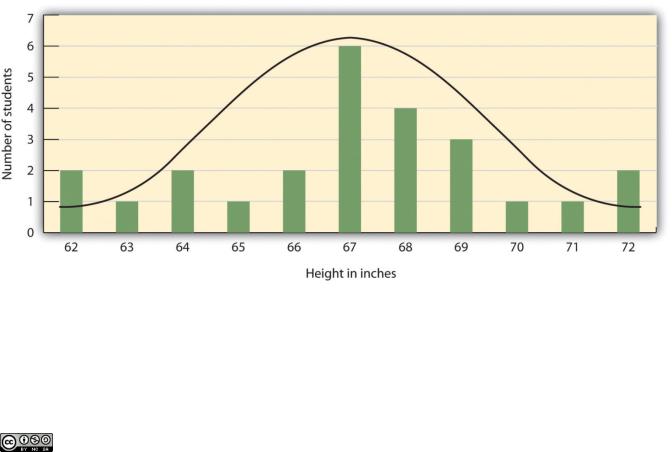

The results of descriptive research projects are analyzed using descriptive statistics—numbers that summarize the distribution of scores on a measured variable. Most variables have distributions similar to that shown in Figure 2.5 "Height Distribution", where most of the scores are located near the center of the distribution, and the distribution is symmetrical and bellshaped.A data distribution that is shaped like a bell is known as anormal distribution.

Table 2.4 Height and Family Income for 25 Students

Student name |

Height in inches |

Family income in dollars |

|

|

|

Lauren |

62 |

48,000 |

|

|

|

Courtnie |

62 |

57,000 |

|

|

|

Leslie |

63 |

93,000 |

|

|

|

Renee |

64 |

107,000 |

|

|

|

Katherine |

64 |

110,000 |

|

|

|

Jordan |

65 |

93,000 |

|

|

|

Rabiah |

66 |

46,000 |

|

|

|

Alina |

66 |

84,000 |

|

|

|

Young Su |

67 |

68,000 |

|

|

|

Martin |

67 |

49,000 |

|

|

|

Hanzhu |

67 |

73,000 |

|

|

|

Caitlin |

67 |

3,800,000 |

|

|

|

Steven |

67 |

107,000 |

|

|

|

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

65 |

Student name |

Height in inches |

Family income in dollars |

|

|

|

|

|

Emily |

67 |

64,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Amy |

68 |

67,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Jonathan |

68 |

51,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Julian |

68 |

48,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Alissa |

68 |

93,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Christine |

69 |

93,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Candace |

69 |

111,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Xiaohua |

69 |

56,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Charlie |

70 |

94,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Timothy |

71 |

73,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Ariane |

72 |

70,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Logan |

72 |

44,000 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2.5 Height Distribution

The distribution of the heights of the students in a class will form a normal distribution. In this sample the mean (M) = 67.12 and the standard deviation (s) = 2.74.

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

66 |

A distribution can be described in terms of its central tendency—that is, the point in the distribution around which the data are centered—and its dispersion, or spread. The arithmetic average, or arithmetic mean, is the most commonly used measure of central tendency. It is computed by calculating the sum of all the scores of the variable and dividing this sum by the number of participants in the distribution (denoted by the letter N). In the data presented

in Figure 2.5 "Height Distribution", the mean height of the students is 67.12 inches. The sample mean is usually indicated by the letter M.

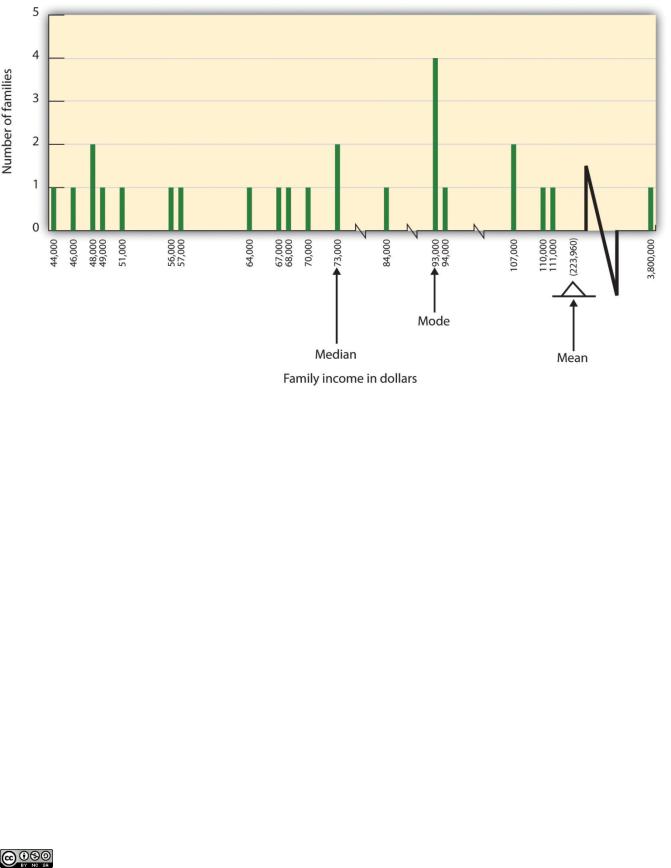

In some cases, however, the data distribution is not symmetrical. This occurs when there are one or more extreme scores (known as outliers) at one end of the distribution. Consider, for instance, the variable of family income (see Figure 2.6 "Family Income Distribution"), which includes an outlier (a value of $3,800,000). In this case the mean is not a good measure of central tendency. Although it appears from Figure 2.6 "Family Income Distribution" that the central tendency of the family income variable should be around $70,000, the mean family income is actually $223,960. The single very extreme income has a disproportionate impact on the mean, resulting in a value that does not well represent the central tendency.

The median is used as an alternative measure of central tendency when distributions are not symmetrical. The median is the score in the center of the distribution, meaning that 50% of the scores are greater than the median and 50% of the scores are less than the median. In our case, the median household income ($73,000) is a much better indication of central tendency than is the mean household income ($223,960).

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

67 |

Figure 2.6 Family Income Distribution

The distribution of family incomes is likely to be nonsymmetrical because some incomes can be very large in comparison to most incomes. In this case the median or the mode is a better indicator of central tendency than is the mean.

A final measure of central tendency, known as the mode, represents the value that occurs most frequently in the distribution. You can see from Figure 2.6 "Family Income Distribution" that the mode for the family income variable is $93,000 (it occurs four times).

In addition to summarizing the central tendency of a distribution, descriptive statistics convey information about how the scores of the variable are spread around the central

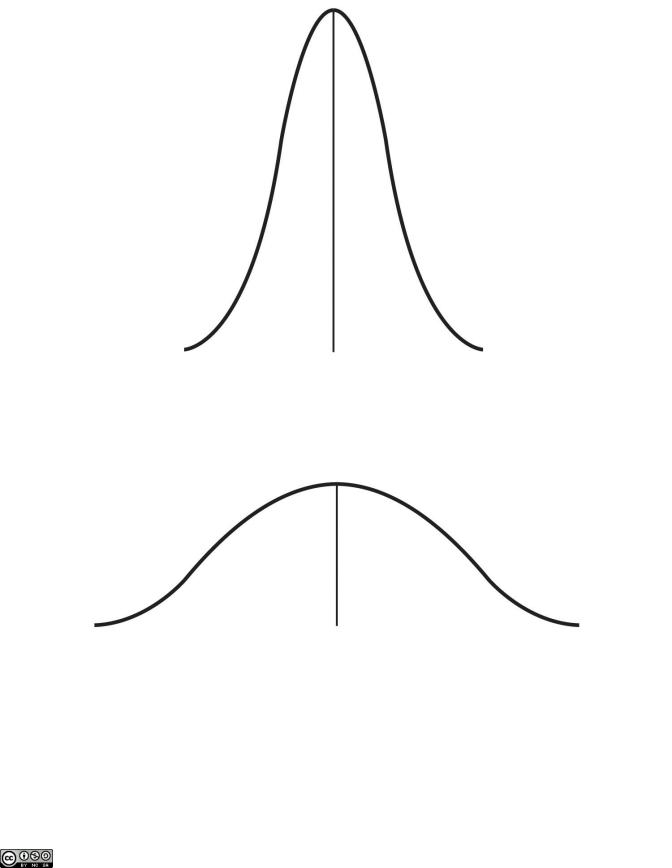

tendency. Dispersion refers to the extent to which the scores are all tightly clustered around the central tendency, like this:

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

68 |

Figure 2.7

Or they may be more spread out away from it, like this:

Figure 2.8

One simple measure of dispersion is to find the largest (the maximum) and the smallest

(the minimum) observed values of the variable and to compute therange of the variable as the maximum observed score minus the minimum observed score. You can check that the range of the height variable in Figure 2.5 "Height Distribution" is 72 – 62 = 10. The standard deviation, symbolized as s, is the most commonly used measure of dispersion. Distributions with a larger

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

69 |