Verb Tenses and Moods

As shown in Table 7, various tenses are used by all the presidents. Some focus on the past, using was/were and some on the future, using will. Similarly for modals, Clinton prefers must, where Nixon favors can/could.

Table 7: The frequency of selected verbs

|

|

Jackson |

Lincoln |

McKinley |

Roosevelt |

Nixon |

Clinton |

|

BE |

11 |

(24 8 |

27 |

7 |

16 |

9 |

|

IS |

6 |

(18) 6 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

17 |

|

ARE |

6 |

(6) 2 |

23 |

13 |

6 |

13 |

|

WILL |

9 |

0 |

22 |

15 |

18 |

27 |

|

WAS/WERE |

0 |

(24) 8 |

12 |

7 |

2 |

5 |

|

HAD |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

MAY |

4 |

(9) 3 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

|

MUST |

4 |

(9) 3 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

CAN/COULD |

3 |

(6) 2 |

2 |

9 |

15 |

8 |

|

SHALL |

3 |

(15) 5 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

Lincoln and McKinley consider the past in their speech, while Jackson, Roosevelt, Nixon and Clinton focus on the present and the future, depending on the focus of their speech.

As for the mood, conditional is used frequently throughout all speeches by using shall, should or ought to, expressing advisability. As for the imperative let us, it is rather a rhetorical tool used to “invite the audience to be part of the answer,” later discussed in the stylistic level (Halamari 256).

Use of Personal Pronouns

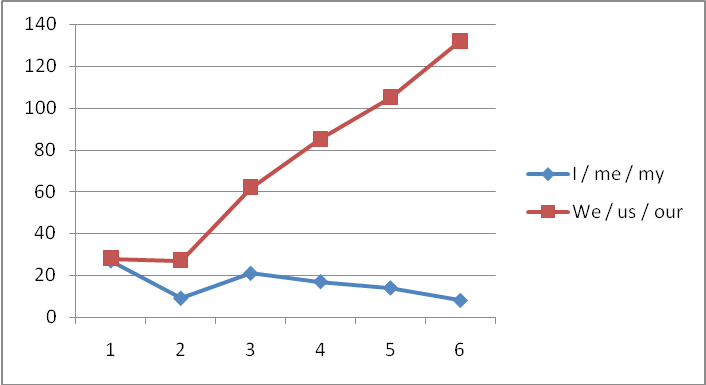

As stated by Halamari, “looking at such a frequent yet non-salient discourse feature as the use of personal pronouns may turn out to be revealing” (259). Indeed, the numbers in Tables 8 and consequently 9 show staggering results, particularly in terms of the use of 1st person singular and plural. There is a sharp decline of the use of 1st person singular, starting from Jackson’s 27 instances of I/me/my down to Clinton’s 8 instances of the same pronoun. In contrast, the use of 1st person plural, we/us/our, increases from Jackson’s 28 instances to Clinton’s 132 instances.

Table 8: The use of pronouns

|

|

Jackson |

Lincoln |

McKinley |

Roosevelt |

Nixon |

Clinton |

|

I / me / my |

27 |

(9) 3 |

21 |

17 |

14 |

8 |

|

You / your |

5 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

We / us / our |

28 |

(27) 9 |

62 |

85 |

105 |

132 |

|

They/ them / their |

16 |

(6) 2 |

44 |

25 |

13 |

20 |

|

TOTAL |

76 |

(42) 14 |

128 |

130 |

136 |

160 |

Chart 3: The evolution of the use of 1st person singular and plural

Where the use of “I may be a sign of ‘self-centeredness,’” so called exclusion strategy, “the use of we is a simple yet powerful inclusion strategy” (Halamari 259). There are some cases where self-reference, i.e. the use of I, “can also be associated with engagement”, but generally, I, me, my focuses on the speaker and excludes the audience (Dontcheva-Navratilova, Some functions 10). Similarly, we “is sometimes used without including the audience,” but only in seldom instance (Halamari 260). What is therefore clearly demonstrated in the above graph is the decrease in use of audience-exclusive strategies and the increase of audience-inclusive strategies over time.

Summary

While all speeches are grammatically similar, in using coordinate as well as subordinate sentences, various tenses and moods as well as personal pronouns, the general complexity and length of sentences has inevitably decreased with time. In Jackson’s or Lincoln’s speech multiple examples of grammatical complexity (fronting, inversion, apposition) can be observed that are only infrequently seen in the speeches of Nixon or Clinton.

Stylistic Level

Presidential speeches are not an ideal place to introduce literary devices, but without using at least some of them, speeches would only be a dull summary of ideas and plans. This section will focus on a “creative approach of the speaker towards language” that somehow sets the speech apart from the others (Cerny 190: translation mine). Speakers gravitate towards a style that fits not only their personality, but mainly communicates with the audience in the most effective way possible. Due to thesis constraints, the following sections will focus only on the most prominent stylistic features of each speech, such as basic literary devices, religious references or audience-involvement strategies.

Literary Devices

Jackson’s Literary Devices

Jackson’s speech contains many metaphors as well as repetition, but it is the formal vocabulary and complex grammar that give the speech its literary feel, rather than the use of literary devices.

The foreign policy adopted by our Government … has been crowned with almost complete success.

…our sons made soldiers to deluge with blood the fields they now till in peace …

To do justice to all and to submit to wrong from none

Lincoln’s Literary Devices

As in case of Jackson, Lincoln’s speech is also an example of figurative language, though elevated to an even higher level. Not without justification, is Lincoln called the father of figurative speech (Griffin). Though only 708 words long, there are many metaphors in his speech, many contrastive pairs and frequent repetition, all very eloquent and fitting, as he puts it.

…on every point and phase of the great contest … (meaning the Civil War)

…to bind up the nation's wounds…

…one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish

McKinley’s Literary Devices

McKinley’s speech, though well intended, is perhaps the least engaging and the most stylistically uninteresting. There are few metaphors, repetitions and contrastive pairs found, and several soundbites.

As heretofore, so hereafter will the nation demonstrate its fitness to administer any new estate which events devolve upon it, and in the fear of God will “take occasion by the hand and make the bounds of freedom wider yet."

Roosevelt’s Literary Devices

In his speech, Roosevelt uses simple, but frequent metaphors, soundbites and also contrastive pairs. He uses topic repetition by beginning several paragraphs in a row with the same phrase. He succeeds in using a simple but communicative style that should maintain the audience’s attention:

…the winds of chance and the hurricanes of disaster… (metaphor)

…moral climate of America… (metaphor)

We will carry on. (soundbite)

However, Roosevelt also uses words with negative connotation very often. The following were found in just one paragraph of 85 words:

disasters, inevitable, problems, unsolvable, epidemics, fatalistic, suffering, epidemics, disease, refused, problems, hurricanes, disaster

Nixon’s Literary Devices

Nixon’s speech repeats Roosevelt’s strategy of very frequent, simple and practical repetition. He also uses contrast, repetition and metaphors, though very simple. There is also the use metonymy: Washington knows best

Unless we in America work to preserve the peace, there will be no peace. Unless we in America work to preserve freedom, there will be no freedom. (contrast, repetition)

Let us continue to bring down the walls of hostility which have divided the world for too long, and to build in their place bridges of understanding (metaphors)

Clinton’s Literary Devices

Clinton’s speech is far from being figurative, but it comes across as sincere and smart. The metaphors are fresh and repetitions are not dull, though they are the most patriotically focused of all the speeches. Clinton uses contrast as well as parallelism.

We must keep our old democracy forever young. (metaphor, contrast)

But the journey of our America must go on. (metaphor)

Religious References

The best way to asses the presence of religion in speeches is to look at Table 9, outlining the number of religious references made. As mentioned earlier, Lincoln’s speech is an exception and contains numerous religious references. As for the other speeches, there does not seem to be a pattern or correlation, though it is surprising that Roosevelt has only one religious reference.

Table 9: Words with religious meaning

|

|

Jackson |

Lincoln |

McKinley |

Roosevelt |

Nixon |

Clinton |

|

Pray, prayer |

1 |

(9) 3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

God, Him, His, Almighty, divine, sacred, bless |

5 |

(42) 14 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

|

Total |

6 |

(51) 17 |

3 |

1 |

7 |

3 |

Audience Involvement Strategies

There are several strategies that according to Halamari “invite the audience to be part of the answer” (256). These strategies are formed by the use of personal pronouns, let’s/let us, let me, vocatives and rhetorical questions. As personal pronouns have already been analyzed separately in the grammatical section, Chart 3 shows the occurrence of the other three strategies:

Chart 3: The use of some audience involvement strategies

The chart shows inconclusive results with the first three presidents, but it is clear that with Nixon and particularly with Clinton, all three strategies are experiencing an increase. To put all these results into better overall perspective, Chart 4 shows combined data, including the use of the inclusive personal pronouns we/us/our.

Chart 4: The use of audience involvement strategies 1833 - 1997

Summary

Jackson’s combination of very long sentences, rich grammatical structures, high level of formality and frequent use of complex and religious vocabulary makes his style a great example of figurative language, which was the norm in the 19th century. This style did not consider involving audience as important, hence the minimum of audience-involvement strategies.

Seeing that Lincoln’s style is very formal, religiously oriented and does not use any audience-involvement or persuasive strategies, it should not be considered a political speech but rather a sermon. Indeed, Witham confirms that Lincoln’s “second inaugural speech gave the nation a sacred memory and [one] of the nation’s greatest secular sermon[s]” (144).

McKinley’s speech does not take inspiration from the speeches of Jackson and Lincoln, for his style is formal and uninspiring. It is not for the lack of use of literary devices, but rather an overall coherence issue, which will be discussed in the Pragmatic section.

Roosevelt’s style is set to reach out to ordinary folks and to motivate them. The speech is, compared to the previous speeches in the corpus, communicative with a lower formality index, but as mentioned before, uses too many negatively charged words. Literary devices are simple and practical, used to engage (rather then impress) the audience.

The style in Nixon’s speech feels more organized and focused than other speeches. The use of literary devices is perhaps too contrived, and there is a clear overuse of the let’s feature.

Clinton’s literary features are far from being figurative, but he certainly manages to be engaging and approachable. This can be explained by the fact that Clinton in 1997, used five times more audience-involvement strategies than Jackson in 1833. His style can be classified as formal, but friendly and involving.

Discourse Level

Discourse analysis tells us more about how the text is held together with the help of reference, ellipsis, substitution, conjunction or lexical cohesion. Lexical cohesion was already discussed in section 9.3 Topical words (Table 4). Conjunctions, such as coordinators and subordinators were discussed in section 10.1 Types and length of sentences (Table 5). As for ellipsis and substitution, both are used by all speakers with various frequencies and a deeper analysis would not yield any practical results pertinent to this study.

Reference

It is worth noting that all speakers use personal, demonstrative or comparative references for things they have already mentioned in the speech.

We began the 20th century with a choice, to harness the Industrial Revolution to our values of free enterprise, conservation, and human decency Those choices made all the difference.

Clinton

From this day forward, let each of us make a solemn commitment in his own heart: to bear his responsibility, to do his part, to live his ideals.

Nixon

However, rather than reference, speakers tend to favor repetition, since it is important to repeat things to the audience.

Coherence

Cohesion physically links actual words and sentences, whereas coherence symbolizes the invisible thread that links the entire discourse. Both are important for the flow of a discourse. However, it will be demonstrated that while features of grammatical cohesion are important, it is the discourse organization and coherence that are far more critical for the successful comprehension and appeal of a political speech.

Jackson’s Cohesion and Coherence

Jackson divides his speech into nine paragraphs, averaging about 100 words per paragraph, and each focusing on just one issue. The most common beginning of a paragraph is a simple noun phrase, usually used as a topic sentence:

So many events have occurred within the last four years

Thanks to these sentences, he moves through the speech topic by topic:

The foreign policy adopted by our Government… In the domestic policy of this Government...

He also nicely connects topics from earlier paragraphs to introduce a new theme:

These great objects are necessarily connected….

As a result, the ideas in the speech are well connected, have a nice flow but tend to be harder to comprehend given the sentence length. Provided the hearer is familiar with this figurative language, however, Jackson’s speech is well organized and also impressive. It should be noted that today’s audience would have a hard time comprehending his language, demonstrating the importance of appropriate background and knowledge.

Lincoln’s Cohesion and Coherence

Given that the speech only has four paragraphs, their beginning sentences are not of real importance. The entire discourse is held together by the extensive use of narrative strategy, i.e. one thing follows another:

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves…. These slaves constituted… interest. All knew that this interest was…. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object…

This example demonstrates a narrative thread in Lincoln’s speech. He is basically telling a story. As such the speech is very enticing and captivating, again, given that the hearer is familiar with Lincoln’s complex linguistic devices.

McKinley’s Cohesion and Coherence

McKinley’s speech is divided into 12 paragraphs, averaging 190 words per paragraph. Its longest paragraph is 532 words making it impossible to maintain the hearer’s attention. Length is an overall problem in McKinely’s speech:

The principles which led to our intervention require that the fundamental law upon which the new government rests should be adapted to secure a government capable of performing the duties and discharging the functions of a separate nation, of observing its international obligations of protecting life and property, insuring order, safety, and liberty, and conforming to the established and historical policy of the United States in its relation to Cuba.

This sentence comes at the end of a paragraph that is already 255 words long and where McKinley rambles on about the importance of the relationship with Cuba. As if that was not enough, he dedicates another paragraph to Cuba, repeating again the same thing. Also, his thanks for being re-elected comes in the middle of the speech, rather than at the beginning. This poor organization combined with constant repetition and wordiness and long-winded sentences negatively impacts cohesion and coherence in McKinley’s speech, making it boring and chaotic.

Roosevelt’s Cohesion and Coherence

In comparison with McKinley, Roosevelt’s speech is approximately 1,900 words long but divided into 37 paragraphs (instead of McKinley’s 12), making the speech more comprehensible. While Roosevelt spaces his ideas nicely, he has a tendency to repeat too often with short, soundbite-like sentences:

Vitality has been preserved. Courage and confidence have been restored. Mental and moral horizons have been extended.

The former feature often interrupts the speech flow, making it too fragmented. The later gives a negative impression, inevitably affecting the hearer’s perception.

Nixon’s Cohesion and Coherence

Nixon apparently enjoyed using extra short paragraphs, as there are 50 in his speech of 1,900 words, making it only 38 words per paragraph on average. Nixon begins 22 sentences by let’s, and also by conjuncts, giving the speech a constant upbeat and energy.

Just as we respect the right…

Let us accept that high…

Above all else, the time has come…

That said, it is difficult for the audience to stay focused when the speech never slows down. The coherence of the speech is interrupted by too many directives and too much involvement demanded from the audience.

Clinton’s Cohesion and Coherence

Clinton separated his speech into 33 paragraphs, with 68 words per paragraph. The speech has a good balance of long and short sentences and uses Lincoln’s effective narrative style, often beginning sentences with adverbs of time or time expressions in order to move the speech forward. He begins in the past:

At this last presidential inauguration…

And what a century it has been…

Along the way,…

Moves onto the present:

Now, for the third time,…

In these four years,…

And then switches to future:

Fellow citizens, let us build…

We will stand mighty …

By doing so, the speech has a solid flow and logical development.

Pragmatic Level

This section deals with what the speaker or writer intended to say and what was the perception of the hearer or reader. In an ideal situation, the items on the list of both participants are identical, meaning all intended ideas and plans are understood exactly the way they were meant. Reality shows though, that there are many conditions that have to be met for the two parties to understand each other perfectly.

The Context: Field, Tenor, Mode

In order to contrast and compare any discourse, it is vital to identify the “specific circumstances and purposes within the act of communication and different contexts and situations in which the communication takes place” (Dontcheva-Navratilova Grammatical 9). The speeches analyzed in this thesis were chosen specifically, as their field, tenor and mode are virtually identical, which is imperative for an objective analysis.

The field, or so called activity, is the same for all six speeches. They are all 2nd inaugural addresses of U.S. presidents.

The tenor, or so called relationship between the participants is alike in that it is always a president versus the audience. Clearly, it is always a different person as a president and different people as audience. The speeches are always public, formal and polite.

The mode, or so called purpose is also the same in all speeches. Newly elected presidents thank the people for being re-elected and attempt to persuade the public to agree with their plans and ideas for the future. The speeches always exist in spoken as well as written form, they are seemingly non-interactive and they are meant to inform and persuade.

Diachronic Changes

Though the tenor, field and mode are somewhat identical in all six speeches, the cultural, historical, religious and political context is inevitably different as the speeches in the corpus are spaced apart by approximately thirty years, starting in 1833 and ending in 1997. When Lincoln spoke in 1863 the South and the North of the United States were at war with each other, the country was in turmoil and people were praying to God to end their fear and suffering. That was the context of the speech, so that is what Lincoln talked about: the war, the South and the North and God. To the contrary, in 1997 America was on the top of the world, with its economic, scientific, cultural and military power, so that is exactly what Clinton focused on. These basic socio-political circumstances of each speech were summarized in section 7 (The history of inaugural speeches), and must be taken into consideration when analyzing each discourse.

Rhetoric

As noted in the theoretical part, rhetoric consists of three principles: ethos, pathos and logos. These principles have been identified in all six speeches and the results depicted in Chart 5.

Chart 5: Means of Persuasion 1833 – 1997

Lincoln’s speech is once again an exception, as there are basically no persuasive strategies found. For this and other reasons already explained in previous sections, it has already been classified as a secular sermon. As for the other speeches, there seems to be a decreasing tendency to use ethos – the strategy, where the speaker tries to seem credible. Though there clearly exist outside influences that affect the credibility of the speaker, as they are unknown to us, only ethos remarks found in the speeches are considered and counted. Logos, the strategy that persuades the listener based on logical reasoning, shows as inconclusive, but steadily used by all speakers. The strategy that is focused on creating a pleasant feeling in the minds of listeners, pathos, is shown as growing over time, demonstrating, above all, the increased need to keep the audience positively inclined towards the speech, toward politics, towards the future.

It should be noted, that the analysis of all persuasive strategies was seriously hindered by the ambiguity of the utterances themselves, and should be assumed somewhat biased based on the following findings.

Firstly, it is difficult to determine where one persuasive strategy begins and another one ends.

In our own lives, let each of us ask—not just what will government do for me, but what can I do for myself? (logos)

Nixon

It shall be displayed to the extent of my humble abilities in continued efforts so to administer the Government as to preserve their liberty and promote their happiness. (ethos)

Jackson

In these utterances, Nixon implores the people to do be independent, using logical reasoning, while Jackson promises to be the best president possible. However, both utterances continue further, creating an entire paragraph of logical or ethical reasoning grouped together. Such instances were classified as a single occurrence, no matter the length of the paragraph, as long as the topic remained the same.

Secondly, in some instances the utterance was ambiguous, containing features of various persuasive strategies:

As times change, so government must change. …our new government is to give all Americans an opportunity—not a guarantee, but a real opportunity—to build better lives. (logos / pathos)

From the above utterance it is difficult to decide whether it functions as logical reasoning (logos) “times change, government must change” or as creating a positive message (pathos) “real opportunity – to build better lives”. In such cases supposition was used to decide which feature was more prominent or if both features were of equal value.

Thirdly, as with any speeches, there is a lot of repetition. One utterance was sometimes repeated in various forms, but still containing the same original message. Again, supposition was employed. That said, and considering all the mentioned constraints, figures in Chart 5 should still be considered a fairly accurate indication of the evolution of means of persuasion between the years 1833-1997.

Conclusion

This discourse analysis of the corpus confirms the hypothesis and demonstrates that between the years 1833-1997 the lexical, grammatical and stylistic complexity of the discourse has continuously decreased. The more contemporary speeches use simpler vocabulary, shorter sentences and less elaborate style. Directly related to the decrease in complexity is the increase in audience-involvement strategies, i.e. the use of we, let’s, rhetorical questions and vocatives. The purpose of the speeches has evolved as well, from a work of art to an audience-engaging communication and information tool.

The study of discourse and pragmatic levels did not yield any conclusive evidence and therefore confirms that the overall coherence and organization of a speech can be good or bad regardless of time. Interestingly, the use of religious expressions did not confirm the hypothesis either, suggesting the probability of personal preference. The assumption of moral and ethical decline was also incorrect, as the study of means of persuasion confirmed the contrary.

The speakers focused less on using ethos strategies, i.e. the mention of themselves, and targeted pathos instead. The results demonstrate a greater frequency over time of positive and motivating utterances, including the increased mention of American and America. Persuasion through logical reasoning is found to be inconclusive, suggesting further background knowledge of the circumstances and the speaker’s preferences is needed to offer a better explanation.

What was not examined in this thesis but certainly should be taken into consideration is the impact mass media has on politics, on the art of persuasion but also on the attention span of the audience. The need for sentence shortening presented itself when President Roosevelt took advantage of a new technology and broadcasted his 2nd inaugural speech live on the radio. Similarly, as Nixon’s speech was the first one in the corpus to be televised, he decided to dramatically increase the audience-involvement feature let’s, hoping to secure people’s positive attitude. This pattern of shortness, appeal and interaction can also be attributed to the growing impact of media on the audience’s attention and needs.

Still, taking into account the discourse levels examined as well as outside circumstances, Halamari is certainly correct in her suggestion that “while we can identify, study and even learn the linguistic markers of ‘good’ political rhetoric, it is impossible to guarantee positive outcomes in the world” (249). All six of the presidents studied in this thesis learned this fact first hand and often the hard way.

Bibliography

Books:

Beard, Adrian. The Language of Politics. Routledge: New York, 2000. Print.

Brinkley, Alan. The Unfinished Nation. McGraw-Hill: New York, 2005. Print.

Brown, Gillian and George Yule. Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: CUP, 1983. Print.

Cerny, Jiri. Uvod do studia jazyka. Rubico: Olomouc, 1998. Print.

Cook, Guy. Discourse. Oxford: London. 1989. Print.

Crystal, David, and Derek Davy. Investigating English Style. Longman: New York,

1969. Print.

Dontcheva-Navratilova, Olga. “Functions of Self-reference in Diplomatic Addresses.” Discourse and Interaction Brno: 2008: 7-21. Print.

Dontcheva-Navratilova, Olga. Grammatical Structures in English: Meaning in Context. Brno: 2005. Print.

Halliday, M.A.K., and Ruqaiya Hasan. Cohesion in English. Pearson Education: Essex, London. 1976. Print.

Witham, Larry. A City Upon a Hill: How Sermons Changed the Course of American History. HarperCollins: New York, 2008. Print.

Yule, George. Pragmatics. Cambridge: CUP, 1996. Print.

Articles:

Halamari, Helena. “On the Language of the Dole-Clinton presidential debates: General Tendencies and Successful Strategies.” Journal of Language and Politics Feb 2008: 247-270. Print.

Horvath, Juraj, “Critical Discourse Analysis of Obama`s Political Discourse.” Language, Literature and Culture in a Changing Transatlantic World: Prešov: Prešovská univerzita v Prešove, 2009. Print.

Miller, Nancy, and William Stiles. “Verbal Familiarity in American Presidential Nomination Acceptance Speeches and Inaugural Addresses (1920-1981).” Social Psychology Quarterly 1986: 72-81. Print.

Web Sites

Assmundson, Mikael. “Persuading the Public: A Linguistic Analysis of Barack Obama’s Speech on ‘Super Tuesday’ 2008.” Hogskolan Dalarna, 2008; www.du.se, 2008. Web. 17 April 2010.

Griffin, Dai. “Lincoln’s Influence on Figurative Language in Nineteenth Century America.” University of Iowa, 2007; www.uiowa.edu, 2007. Web. 17 April 2010.

“Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.: for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 1989; Bartleby.com, 2001. Web. 17 April 2010.

Other

Scott, M., 2004, WordSmith Tools version 4, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 0-19-459400-9.

Table List

Table 1: Word Statistics

Table 2: Chief Topics

Table 3: Most Frequently Used Words

Table 4: Topic Words

Table 5: Complex Words

Table 6: Coordinators and Subordinators

Table 7: The Frequency of Selected Verbs

Table 8: The Use of Personal Pronouns

Table 9: Words with Religious Meaning

Chart List

Chart 1: Complex Words Decrease Between 1833-1997

Chart 2: The Evolution of the Use of 1st person Singular and Plural

Chart 3: The Use of Some Audience Involvement Strategies

Chart 4: The Use of Audience Involvement Strategies 1833 - 1997

Chart 5: Means of Persuasion 1833 – 1997

Appendix 1 - Andrew Jackson’s 2nd Inaugural Speech

Fellow-Citizens: THE will of the American people, expressed through their unsolicited suffrages, calls me before you to pass through the solemnities preparatory to taking upon myself the duties of President of the United States for another term. For their approbation of my public conduct through a period which has not been without its difficulties, and for this renewed expression of their confidence in my good intentions, I am at a loss for terms adequate to the expression of my gratitude. It shall be displayed to the extent of my humble abilities in continued efforts so to administer the Government as to preserve their liberty and promote their happiness.

So many events have occurred within the last four years which have necessarily called forth—sometimes under circumstances the most delicate and painful—my views of the principles and policy which ought to be pursued by the General Government that I need on this occasion but allude to a few leading considerations connected with some of them.

The foreign policy adopted by our Government soon after the formation of our present Constitution, and very generally pursued by successive Administrations, has been crowned with almost complete success, and has elevated our character among the nations of the earth. To do justice to all and to submit to wrong from none has been during my Administration its governing maxim, and so happy have been its results that we are not only at peace with all the world, but have few causes of controversy, and those of minor importance, remaining unadjusted.

In the domestic policy of this Government there are two objects which especially deserve the attention of the people and their representatives, and which have been and will continue to be the subjects of my increasing solicitude. They are the preservation of the rights of the several States and the integrity of the Union.

These great objects are necessarily connected, and can only be attained by an enlightened exercise of the powers of each within its appropriate sphere in conformity with the public will constitutionally expressed. To this end it becomes the duty of all to yield a ready and patriotic submission to the laws constitutionally enacted, and thereby promote and strengthen a proper confidence in those institutions of the several States and of the United States which the people themselves have ordained for their own government.

My experience in public concerns and the observation of a life somewhat advanced confirm the opinions long since imbibed by me, that the destruction of our State governments or the annihilation of their control over the local concerns of the people would lead directly to revolution and anarchy, and finally to despotism and military domination. In proportion, therefore, as the General Government encroaches upon the rights of the States, in the same proportion does it impair its own power and detract from its ability to fulfill the purposes of its creation. Solemnly impressed with these considerations, my countrymen will ever find me ready to exercise my constitutional powers in arresting measures which may directly or indirectly encroach upon the rights of the States or tend to consolidate all political power in the General Government. But of equal, and, indeed, of incalculable, importance is the union of these States, and the sacred duty of all to contribute to its preservation by a liberal support of the General Government in the exercise of its just powers. You have been wisely admonished to "accustom yourselves to think and speak of the Union as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity, watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety, discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned, and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of any attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts." Without union our independence and liberty would never have been achieved; without union they never can be maintained. Divided into twenty-four, or even a smaller number, of separate communities, we shall see our internal trade burdened with numberless restraints and exactions; communication between distant points and sections obstructed or cut off; our sons made soldiers to deluge with blood the fields they now till in peace; the mass of our people borne down and impoverished by taxes to support armies and navies, and military leaders at the head of their victorious legions becoming our lawgivers and judges. The loss of liberty, of all good government, of peace, plenty, and happiness, must inevitably follow a dissolution of the Union. In supporting it, therefore, we support all that is dear to the freeman and the philanthropist.

The time at which I stand before you is full of interest. The eyes of all nations are fixed on our Republic. The event of the existing crisis will be decisive in the opinion of mankind of the practicability of our federal system of government. Great is the stake placed in our hands; great is the responsibility which must rest upon the people of the United States. Let us realize the importance of the attitude in which we stand before the world. Let us exercise forbearance and firmness. Let us extricate our country from the dangers which surround it and learn wisdom from the lessons they inculcate.

Deeply impressed with the truth of these observations, and under the obligation of that solemn oath which I am about to take, I shall continue to exert all my faculties to maintain the just powers of the Constitution and to transmit unimpaired to posterity the blessings of our Federal Union. At the same time, it will be my aim to inculcate by my official acts the necessity of exercising by the General Government those powers only that are clearly delegated; to encourage simplicity and economy in the expenditures of the Government; to raise no more money from the people than may be requisite for these objects, and in a manner that will best promote the interests of all classes of the community and of all portions of the Union. Constantly bearing in mind that in entering into society "individuals must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest," it will be my desire so to discharge my duties as to foster with our brethren in all parts of the country a spirit of liberal concession and compromise, and, by reconciling our fellow-citizens to those partial sacrifices which they must unavoidably make for the preservation of a greater good, to recommend our invaluable Government and Union to the confidence and affections of the American people.

Finally, it is my most fervent prayer to that Almighty Being before whom I now stand, and who has kept us in His hands from the infancy of our Republic to the present day, that He will so overrule all my intentions and actions and inspire the hearts of my fellow-citizens that we may be preserved from dangers of all kinds and continue forever a united and happy people.

Appendix 2 – Abraham Lincoln’s 2nd Inaugural Speech

Fellow-Countrymen: AT this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be pursued seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, urgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh." If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Appendix 3 – William McKinley’s 2nd Inaugural Speech

My Fellow-Citizens: WHEN we assembled here on the 4th of March, 1897, there was great anxiety with regard to our currency and credit. None exists now. Then our Treasury receipts were inadequate to meet the current obligations of the Government. Now they are sufficient for all public needs, and we have a surplus instead of a deficit. Then I felt constrained to convene the Congress in extraordinary session to devise revenues to pay the ordinary expenses of the Government. Now I have the satisfaction to announce that the Congress just closed has reduced taxation in the sum of $41,000,000. Then there was deep solicitude because of the long depression in our manufacturing, mining, agricultural, and mercantile industries and the consequent distress of our laboring population. Now every avenue of production is crowded with activity, labor is well employed, and American products find good markets at home and abroad.

Our diversified productions, however, are increasing in such unprecedented volume as to admonish us of the necessity of still further enlarging our foreign markets by broader commercial relations. For this purpose reciprocal trade arrangements with other nations should in liberal spirit be carefully cultivated and promoted.

The national verdict of 1896 has for the most part been executed. Whatever remains unfulfilled is a continuing obligation resting with undiminished force upon the Executive and the Congress. But fortunate as our condition is, its permanence can only be assured by sound business methods and strict economy in national administration and legislation. We should not permit our great prosperity to lead us to reckless ventures in business or profligacy in public expenditures. While the Congress determines the objects and the sum of appropriations, the officials of the executive departments are responsible for honest and faithful disbursement, and it should be their constant care to avoid waste and extravagance.

Honesty, capacity, and industry are nowhere more indispensable than in public employment. These should be fundamental requisites to original appointment and the surest guaranties against removal.

Four years ago we stood on the brink of war without the people knowing it and without any preparation or effort at preparation for the impending peril. I did all that in honor could be done to avert the war, but without avail. It became inevitable; and the Congress at its first regular session, without party division, provided money in anticipation of the crisis and in preparation to meet it. It came. The result was signally favorable to American arms and in the highest degree honorable to the Government. It imposed upon us obligations from which we cannot escape and from which it would be dishonorable to seek escape. We are now at peace with the world, and it is my fervent prayer that if differences arise between us and other powers they may be settled by peaceful arbitration and that hereafter we may be spared the horrors of war.

Intrusted by the people for a second time with the office of President, I enter upon its administration appreciating the great responsibilities which attach to this renewed honor and commission, promising unreserved devotion on my part to their faithful discharge and reverently invoking for my guidance the direction and favor of Almighty God. I should shrink from the duties this day assumed if I did not feel that in their performance I should have the co-operation of the wise and patriotic men of all parties. It encourages me for the great task which I now undertake to believe that those who voluntarily committed to me the trust imposed upon the Chief Executive of the Republic will give to me generous support in my duties to "preserve, protect, and defend, the Constitution of the United States" and to "care that the laws be faithfully executed." The national purpose is indicated through a national election. It is the constitutional method of ascertaining the public will. When once it is registered it is a law to us all, and faithful observance should follow its decrees.

Strong hearts and helpful hands are needed, and, fortunately, we have them in every part of our beloved country. We are reunited. Sectionalism has disappeared. Division on public questions can no longer be traced by the war maps of 1861. These old differences less and less disturb the judgment. Existing problems demand the thought and quicken the conscience of the country, and the responsibility for their presence, as well as for their righteous settlement, rests upon us all—no more upon me than upon you. There are some national questions in the solution of which patriotism should exclude partisanship. Magnifying their difficulties will not take them off our hands nor facilitate their adjustment. Distrust of the capacity, integrity, and high purposes of the American people will not be an inspiring theme for future political contests. Dark pictures and gloomy forebodings are worse than useless. These only becloud, they do not help to point the way of safety and honor. "Hope maketh not ashamed." The prophets of evil were not the builders of the Republic, nor in its crises since have they saved or served it. The faith of the fathers was a mighty force in its creation, and the faith of their descendants has wrought its progress and furnished its defenders. They are obstructionists who despair, and who would destroy confidence in the ability of our people to solve wisely and for civilization the mighty problems resting upon them. The American people, intrenched in freedom at home, take their love for it with them wherever they go, and they reject as mistaken and unworthy the doctrine that we lose our own liberties by securing the enduring foundations of liberty to others. Our institutions will not deteriorate by extension, and our sense of justice will not abate under tropic suns in distant seas. As heretofore, so hereafter will the nation demonstrate its fitness to administer any new estate which events devolve upon it, and in the fear of God will "take occasion by the hand and make the bounds of freedom wider yet." If there are those among us who would make our way more difficult, we must not be disheartened, but the more earnestly dedicate ourselves to the task upon which we have rightly entered. The path of progress is seldom smooth. New things are often found hard to do. Our fathers found them so. We find them so. They are inconvenient. They cost us something. But are we not made better for the effort and sacrifice, and are not those we serve lifted up and blessed?

We will be consoled, too, with the fact that opposition has confronted every onward movement of the Republic from its opening hour until now, but without success. The Republic has marched on and on, and its step has exalted freedom and humanity. We are undergoing the same ordeal as did our predecessors nearly a century ago. We are following the course they blazed. They triumphed. Will their successors falter and plead organic impotency in the nation? Surely after 125 years of achievement for mankind we will not now surrender our equality with other powers on matters fundamental and essential to nationality. With no such purpose was the nation created. In no such spirit has it developed its full and independent sovereignty. We adhere to the principle of equality among ourselves, and by no act of ours will we assign to ourselves a subordinate rank in the family of nations.

My fellow-citizens, the public events of the past four years have gone into history. They are too near to justify recital. Some of them were unforeseen; many of them momentous and far-reaching in their consequences to ourselves and our relations with the rest of the world. The part which the United States bore so honorably in the thrilling scenes in China, while new to American life, has been in harmony with its true spirit and best traditions, and in dealing with the results its policy will be that of moderation and fairness.

We face at this moment a most important question that of the future relations of the United States and Cuba. With our near neighbors we must remain close friends. The declaration of the purposes of this Government in the resolution of April 20, 1898, must be made good. Ever since the evacuation of the island by the army of Spain, the Executive, with all practicable speed, has been assisting its people in the successive steps necessary to the establishment of a free and independent government prepared to assume and perform the obligations of international law which now rest upon the United States under the treaty of Paris. The convention elected by the people to frame a constitution is approaching the completion of its labors. The transfer of American control to the new government is of such great importance, involving an obligation resulting from our intervention and the treaty of peace, that I am glad to be advised by the recent act of Congress of the policy which the legislative branch of the Government deems essential to the best interests of Cuba and the United States. The principles which led to our intervention require that the fundamental law upon which the new government rests should be adapted to secure a government capable of performing the duties and discharging the functions of a separate nation, of observing its international obligations of protecting life and property, insuring order, safety, and liberty, and conforming to the established and historical policy of the United States in its relation to Cuba.

The peace which we are pledged to leave to the Cuban people must carry with it the guaranties of permanence. We became sponsors for the pacification of the island, and we remain accountable to the Cubans, no less than to our own country and people, for the reconstruction of Cuba as a free commonwealth on abiding foundations of right, justice, liberty, and assured order. Our enfranchisement of the people will not be completed until free Cuba shall "be a reality, not a name; a perfect entity, not a hasty experiment bearing within itself the elements of failure."

While the treaty of peace with Spain was ratified on the 6th of February, 1899, and ratifications were exchanged nearly two years ago, the Congress has indicated no form of government for the Philippine Islands. It has, however, provided an army to enable the Executive to suppress insurrection, restore peace, give security to the inhabitants, and establish the authority of the United States throughout the archipelago. It has authorized the organization of native troops as auxiliary to the regular force. It has been advised from time to time of the acts of the military and naval officers in the islands, of my action in appointing civil commissions, of the instructions with which they were charged, of their duties and powers, of their recommendations, and of their several acts under executive commission, together with the very complete general information they have submitted. These reports fully set forth the conditions, past and present, in the islands, and the instructions clearly show the principles which will guide the Executive until the Congress shall, as it is required to do by the treaty, determine "the civil rights and political status of the native inhabitants." The Congress having added the sanction of its authority to the powers already possessed and exercised by the Executive under the Constitution, thereby leaving with the Executive the responsibility for the government of the Philippines, I shall continue the efforts already begun until order shall be restored throughout the islands, and as fast as conditions permit will establish local governments, in the formation of which the full co-operation of the people has been already invited, and when established will encourage the people to administer them. The settled purpose, long ago proclaimed, to afford the inhabitants of the islands self-government as fast as they were ready for it will be pursued with earnestness and fidelity. Already something has been accomplished in this direction. The Government's representatives, civil and military, are doing faithful and noble work in their mission of emancipation and merit the approval and support of their countrymen. The most liberal terms of amnesty have already been communicated to the insurgents, and the way is still open for those who have raised their arms against the Government for honorable submission to its authority. Our countrymen should not be deceived. We are not waging war against the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands. A portion of them are making war against the United States. By far the greater part of the inhabitants recognize American sovereignty and welcome it as a guaranty of order and of security for life, property, liberty, freedom of conscience, and the pursuit of happiness. To them full protection will be given. They shall not be abandoned. We will not leave the destiny of the loyal millions the islands to the disloyal thousands who are in rebellion against the United States. Order under civil institutions will come as soon as those who now break the peace shall keep it. Force will not be needed or used when those who make war against us shall make it no more. May it end without further bloodshed, and there be ushered in the reign of peace to be made permanent by a government of liberty under law!

Appendix 4 – Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 2nd Inaugural Speech

WHEN four years ago we met to inaugurate a President, the Republic, single-minded in anxiety, stood in spirit here. We dedicated ourselves to the fulfillment of a vision—to speed the time when there would be for all the people that security and peace essential to the pursuit of happiness. We of the Republic pledged ourselves to drive from the temple of our ancient faith those who had profaned it; to end by action, tireless and unafraid, the stagnation and despair of that day. We did those first things first.

Our covenant with ourselves did not stop there. Instinctively we recognized a deeper need—the need to find through government the instrument of our united purpose to solve for the individual the ever-rising problems of a complex civilization. Repeated attempts at their solution without the aid of government had left us baffled and bewildered. For, without that aid, we had been unable to create those moral controls over the services of science which are necessary to make science a useful servant instead of a ruthless master of mankind. To do this we knew that we must find practical controls over blind economic forces and blindly selfish men.

We of the Republic sensed the truth that democratic government has innate capacity to protect its people against disasters once considered inevitable, to solve problems once considered unsolvable. We would not admit that we could not find a way to master economic epidemics just as, after centuries of fatalistic suffering, we had found a way to master epidemics of disease. We refused to leave the problems of our common welfare to be solved by the winds of chance and the hurricanes of disaster.

In this we Americans were discovering no wholly new truth; we were writing a new chapter in our book of self-government.

This year marks the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the Constitutional Convention which made us a nation. At that Convention our forefathers found the way out of the chaos which followed the Revolutionary War; they created a strong government with powers of united action sufficient then and now to solve problems utterly beyond individual or local solution. A century and a half ago they established the Federal Government in order to promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to the American people.

Today we invoke those same powers of government to achieve the same objectives.

Four years of new experience have not belied our historic instinct. They hold out the clear hope that government within communities, government within the separate States, and government of the United States can do the things the times require, without yielding its democracy. Our tasks in the last four years did not force democracy to take a holiday.

Nearly all of us recognize that as intricacies of human relationships increase, so power to govern them also must increase—power to stop evil; power to do good. The essential democracy of our Nation and the safety of our people depend not upon the absence of power, but upon lodging it with those whom the people can change or continue at stated intervals through an honest and free system of elections. The Constitution of 1787 did not make our democracy impotent.

In fact, in these last four years, we have made the exercise of all power more democratic; for we have begun to bring private autocratic powers into their proper subordination to the public's government. The legend that they were invincible—above and beyond the processes of a democracy—has been shattered. They have been challenged and beaten.

Our progress out of the depression is obvious. But that is not all that you and I mean by the new order of things. Our pledge was not merely to do a patchwork job with secondhand materials. By using the new materials of social justice we have undertaken to erect on the old foundations a more enduring structure for the better use of future generations.

In that purpose we have been helped by achievements of mind and spirit. Old truths have been relearned; untruths have been unlearned. We have always known that heedless self-interest was bad morals; we know now that it is bad economics. Out of the collapse of a prosperity whose builders boasted their practicality has come the conviction that in the long run economic morality pays. We are beginning to wipe out the line that divides the practical from the ideal; and in so doing we are fashioning an instrument of unimagined power for the establishment of a morally better world.

This new understanding undermines the old admiration of worldly success as such. We are beginning to abandon our tolerance of the abuse of power by those who betray for profit the elementary decencies of life.

In this process evil things formerly accepted will not be so easily condoned. Hard-headedness will not so easily excuse hardheartedness. We are moving toward an era of good feeling. But we realize that there can be no era of good feeling save among men of good will.

For these reasons I am justified in believing that the greatest change we have witnessed has been the change in the moral climate of America.

Among men of good will, science and democracy together offer an ever-richer life and ever-larger satisfaction to the individual. With this change in our moral climate and our rediscovered ability to improve our economic order, we have set our feet upon the road of enduring progress.

Shall we pause now and turn our back upon the road that lies ahead? Shall we call this the promised land? Or, shall we continue on our way? For "each age is a dream that is dying, or one that is coming to birth."

Many voices are heard as we face a great decision. Comfort says, "Tarry a while." Opportunism says, "This is a good spot." Timidity asks, "How difficult is the road ahead?"

True, we have come far from the days of stagnation and despair. Vitality has been preserved. Courage and confidence have been restored. Mental and moral horizons have been extended.

But our present gains were won under the pressure of more than ordinary circumstances. Advance became imperative under the goad of fear and suffering. The times were on the side of progress.

To hold to progress today, however, is more difficult. Dulled conscience, irresponsibility, and ruthless self-interest already reappear. Such symptoms of prosperity may become portents of disaster! Prosperity already tests the persistence of our progressive purpose.

Let us ask again: Have we reached the goal of our vision of that fourth day of March 1933? Have we found our happy valley?

I see a great nation, upon a great continent, blessed with a great wealth of natural resources. Its hundred and thirty million people are at peace among themselves; they are making their country a good neighbor among the nations. I see a United States which can demonstrate that, under democratic methods of government, national wealth can be translated into a spreading volume of human comforts hitherto unknown, and the lowest standard of living can be raised far above the level of mere subsistence.

But here is the challenge to our democracy: In this nation I see tens of millions of its citizens—a substantial part of its whole population—who at this very moment are denied the greater part of what the very lowest standards of today call the necessities of life.

I see millions of families trying to live on incomes so meager that the pall of family disaster hangs over them day by day.

I see millions whose daily lives in city and on farm continue under conditions labeled indecent by a so-called polite society half a century ago.

I see millions denied education, recreation, and the opportunity to better their lot and the lot of their children.

I see millions lacking the means to buy the products of farm and factory and by their poverty denying work and productiveness to many other millions.

I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.

It is not in despair that I paint you that picture. I paint it for you in hope—because the Nation, seeing and understanding the injustice in it, proposes to paint it out. We are determined to make every American citizen the subject of his country's interest and concern; and we will never regard any faithful law-abiding group within our borders as superfluous. The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.

If I know aught of the spirit and purpose of our Nation, we will not listen to Comfort, Opportunism, and Timidity. We will carry on.

Overwhelmingly, we of the Republic are men and women of good will; men and women who have more than warm hearts of dedication; men and women who have cool heads and willing hands of practical purpose as well. They will insist that every agency of popular government use effective instruments to carry out their will.

Government is competent when all who compose it work as trustees for the whole people. It can make constant progress when it keeps abreast of all the facts. It can obtain justified support and legitimate criticism when the people receive true information of all that government does.

If I know aught of the will of our people, they will demand that these conditions of effective government shall be created and maintained. They will demand a nation uncorrupted by cancers of injustice and, therefore, strong among the nations in its example of the will to peace.

Today we reconsecrate our country to long-cherished ideals in a suddenly changed civilization. In every land there are always at work forces that drive men apart and forces that draw men together. In our personal ambitions we are individualists. But in our seeking for economic and political progress as a nation, we all go up, or else we all go down, as one people.

To maintain a democracy of effort requires a vast amount of patience in dealing with differing methods, a vast amount of humility. But out of the confusion of many voices rises an understanding of dominant public need. Then political leadership can voice common ideals, and aid in their realization.

In taking again the oath of office as President of the United States, I assume the solemn obligation of leading the American people forward along the road over which they have chosen to advance.

While this duty rests upon me I shall do my utmost to speak their purpose and to do their will, seeking Divine guidance to help us each and every one to give light to them that sit in darkness and to guide our feet into the way of peace.

Appendix 5 – Richard Nixon’s 2nd Inaugural Speech

Mr. Vice President, Mr. Speaker, Mr. Chief Justice, Senator Cook, Mrs. Eisenhower, and my fellow citizens of this great and good country we share together: When we met here four years ago, America was bleak in spirit, depressed by the prospect of seemingly endless war abroad and of destructive conflict at home.

As we meet here today, we stand on the threshold of a new era of peace in the world.

The central question before us is: How shall we use that peace? Let us resolve that this era we are about to enter will not be what other postwar periods have so often been: a time of retreat and isolation that leads to stagnation at home and invites new danger abroad.

Let us resolve that this will be what it can become: a time of great responsibilities greatly borne, in which we renew the spirit and the promise of America as we enter our third century as a nation.

This past year saw far-reaching results from our new policies for peace. By continuing to revitalize our traditional friendships, and by our missions to Peking and to Moscow, we were able to establish the base for a new and more durable pattern of relationships among the nations of the world. Because of America's bold initiatives, 1972 will be long remembered as the year of the greatest progress since the end of World War II toward a lasting peace in the world.

The peace we seek in the world is not the flimsy peace which is merely an interlude between wars, but a peace which can endure for generations to come.

It is important that we understand both the necessity and the limitations of America's role in maintaining that peace.

Unless we in America work to preserve the peace, there will be no peace.

Unless we in America work to preserve freedom, there will be no freedom.

But let us clearly understand the new nature of America's role, as a result of the new policies we have adopted over these past four years.

We shall respect our treaty commitments.

We shall support vigorously the principle that no country has the right to impose its will or rule on another by force.

We shall continue, in this era of negotiation, to work for the limitation of nuclear arms, and to reduce the danger of confrontation between the great powers.

We shall do our share in defending peace and freedom in the world. But we shall expect others to do their share.

The time has passed when America will make every other nation's conflict our own, or make every other nation's future our responsibility, or presume to tell the people of other nations how to manage their own affairs.

Just as we respect the right of each nation to determine its own future, we also recognize the responsibility of each nation to secure its own future.

Just as America's role is indispensable in preserving the world's peace, so is each nation's role indispensable in preserving its own peace.

Together with the rest of the world, let us resolve to move forward from the beginnings we have made. Let us continue to bring down the walls of hostility which have divided the world for too long, and to build in their place bridges of understanding—so that despite profound differences between systems of government, the people of the world can be friends.

Let us build a structure of peace in the world in which the weak are as safe as the strong—in which each respects the right of the other to live by a different system—in which those who would influence others will do so by the strength of their ideas, and not by the force of their arms.

Let us accept that high responsibility not as a burden, but gladly—gladly because the chance to build such a peace is the noblest endeavor in which a nation can engage; gladly, also, because only if we act greatly in meeting our responsibilities abroad will we remain a great Nation, and only if we remain a great Nation will we act greatly in meeting our challenges at home.

We have the chance today to do more than ever before in our history to make life better in America—to ensure better education, better health, better housing, better transportation, a cleaner environment—to restore respect for law, to make our communities more livable—and to insure the God-given right of every American to full and equal opportunity.

Because the range of our needs is so great—because the reach of our opportunities is so great—let us be bold in our determination to meet those needs in new ways.

Just as building a structure of peace abroad has required turning away from old policies that failed, so building a new era of progress at home requires turning away from old policies that have failed.

Abroad, the shift from old policies to new has not been a retreat from our responsibilities, but a better way to peace.

And at home, the shift from old policies to new will not be a retreat from our responsibilities, but a better way to progress.

Abroad and at home, the key to those new responsibilities lies in the placing and the division of responsibility. We have lived too long with the consequences of attempting to gather all power and responsibility in Washington.

Abroad and at home, the time has come to turn away from the condescending policies of paternalism—of "Washington knows best."

A person can be expected to act responsibly only if he has responsibility. This is human nature. So let us encourage individuals at home and nations abroad to do more for themselves, to decide more for themselves. Let us locate responsibility in more places. Let us measure what we will do for others by what they will do for themselves.

That is why today I offer no promise of a purely governmental solution for every problem. We have lived too long with that false promise. In trusting too much in government, we have asked of it more than it can deliver. This leads only to inflated expectations, to reduced individual effort, and to a disappointment and frustration that erode confidence both in what government can do and in what people can do.

Government must learn to take less from people so that people can do more for themselves.

Let us remember that America was built not by government, but by people—not by welfare, but by work—not by shirking responsibility, but by seeking responsibility.

In our own lives, let each of us ask—not just what will government do for me, but what can I do for myself?

In the challenges we face together, let each of us ask—not just how can government help, but how can I help?

Your National Government has a great and vital role to play. And I pledge to you that where this Government should act, we will act boldly and we will lead boldly. But just as important is the role that each and every one of us must play, as an individual and as a member of his own community.

From this day forward, let each of us make a solemn commitment in his own heart: to bear his responsibility, to do his part, to live his ideals—so that together, we can see the dawn of a new age of progress for America, and together, as we celebrate our 200th anniversary as a nation, we can do so proud in the fulfillment of our promise to ourselves and to the world.

As America's longest and most difficult war comes to an end, let us again learn to debate our differences with civility and decency. And let each of us reach out for that one precious quality government cannot provide—a new level of respect for the rights and feelings of one another, a new level of respect for the individual human dignity which is the cherished birthright of every American.

Above all else, the time has come for us to renew our faith in ourselves and in America.

In recent years, that faith has been challenged.

Our children have been taught to be ashamed of their country, ashamed of their parents, ashamed of America's record at home and of its role in the world.

At every turn, we have been beset by those who find everything wrong with America and little that is right. But I am confident that this will not be the judgment of history on these remarkable times in which we are privileged to live.

America's record in this century has been unparalleled in the world's history for its responsibility, for its generosity, for its creativity and for its progress.

Let us be proud that our system has produced and provided more freedom and more abundance, more widely shared, than any other system in the history of the world.

Let us be proud that in each of the four wars in which we have been engaged in this century, including the one we are now bringing to an end, we have fought not for our selfish advantage, but to help others resist aggression.

Let us be proud that by our bold, new initiatives, and by our steadfastness for peace with honor, we have made a break-through toward creating in the world what the world has not known before—a structure of peace that can last, not merely for our time, but for generations to come.

We are embarking here today on an era that presents challenges great as those any nation, or any generation, has ever faced.

We shall answer to God, to history, and to our conscience for the way in which we use these years.

As I stand in this place, so hallowed by history, I think of others who have stood here before me. I think of the dreams they had for America, and I think of how each recognized that he needed help far beyond himself in order to make those dreams come true.

Today, I ask your prayers that in the years ahead I may have God's help in making decisions that are right for America, and I pray for your help so that together we may be worthy of our challenge.

Let us pledge together to make these next four years the best four years in America's history, so that on its 200th birthday America will be as young and as vital as when it began, and as bright a beacon of hope for all the world.

Let us go forward from here confident in hope, strong in our faith in one another, sustained by our faith in God who created us, and striving always to serve His purpose.

Appendix 6 – William Clinton’s 2nd Inaugural Speech

My fellow citizens: At this last presidential inauguration of the 20th century, let us lift our eyes toward the challenges that await us in the next century. It is our great good fortune that time and chance have put us not only at the edge of a new century, in a new millennium, but on the edge of a bright new prospect in human affairs—a moment that will define our course, and our character, for decades to come. We must keep our old democracy forever young. Guided by the ancient vision of a promised land, let us set our sights upon a land of new promise.

The promise of America was born in the 18th century out of the bold conviction that we are all created equal. It was extended and preserved in the 19th century, when our nation spread across the continent, saved the union, and abolished the awful scourge of slavery.

Then, in turmoil and triumph, that promise exploded onto the world stage to make this the American Century.

And what a century it has been. America became the world’s mightiest industrial power; saved the world from tyranny in two world wars and a long cold war; and time and again, reached out across the globe to millions who, like us, longed for the blessings of liberty.

Along the way, Americans produced a great middle class and security in old age; built unrivaled centers of learning and opened public schools to all; split the atom and explored the heavens; invented the computer and the microchip; and deepened the wellspring of justice by making a revolution in civil rights for African Americans and all minorities, and extending the circle of citizenship, opportunity and dignity to women.

Now, for the third time, a new century is upon us, and another time to choose. We began the 19th century with a choice, to spread our nation from coast to coast. We began the 20th century with a choice, to harness the Industrial Revolution to our values of free enterprise, conservation, and human decency. Those choices made all the difference. At the dawn of the 21st century a free people must now choose to shape the forces of the Information Age and the global society, to unleash the limitless potential of all our people, and, yes, to form a more perfect union.

When last we gathered, our march to this new future seemed less certain than it does today. We vowed then to set a clear course to renew our nation.

In these four years, we have been touched by tragedy, exhilarated by challenge, strengthened by achievement. America stands alone as the world’s indispensable nation. Once again, our economy is the strongest on Earth. Once again, we are building stronger families, thriving communities, better educational opportunities, a cleaner environment. Problems that once seemed destined to deepen now bend to our efforts: our streets are safer and record numbers of our fellow citizens have moved from welfare to work.

And once again, we have resolved for our time a great debate over the role of government. Today we can declare: Government is not the problem, and government is not the solution. We—the American people—we are the solution. Our founders understood that well and gave us a democracy strong enough to endure for centuries, flexible enough to face our common challenges and advance our common dreams in each new day.