методология / haritonchik / харитончик книга по словообразованию

.pdfMINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF BELARUS

Minsk State Linguistic University

TEXTS ON ENGLISH WORD FORMATION

READER IN ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY

Minsk 2005

0

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ БЕЛАРУСЬ

Минский государственный лингвистический университет

СЛОВООБРАЗОВАНИЕ В АНГЛИЙСКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ

ХРЕСТОМАТИЯ ПО ЛЕКСИКОЛОГИИ АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА

Минск 2005

1

УДК 802.0–55

ББК 81.2Ан

С483

Со с т а в и т е л и: З.А.Харитончик, И.В.Ключникова

Ре ц е н з е н т ы: А.В.Посох, кандидат филологических наук, доцент (БГТУ); С.А.Игнатова, кандидат филологических наук, доцент (МГЛУ)

Ре к о м е н д о в а н о Республиканским УМО вузов по лингвистическому образованию

С483 Словообразование в английском языке = Texts on English word formation: Хрестоматия по лексикологии английского языка / сост. З.А.Харитончик, И.В.Ключникова. – Мн.: МГЛУ, 2005. – 185 с.

Хрестоматия включает отрывки из наиболее значимых работ по теории словообразования, изданных в последние десятилетия, и знакомит студентов с ключевыми проблемами исследования словообразовательной подсистемы современного английского языка и их решениями, предлагаемыми в разных научных парадигмах.

Предназначена для студентов-лингвистов, изучающих английский язык, и может быть использована в курсах теории английского языка, а также при подготовке курсовых и дипломных работ, магистерских диссертаций.

УДК 802.0–55

ББК 81.2 Ан

© Минский государственный лингвистический университет, 2005

2

CONTENTS

PREFACE … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … .… 4

Heatherington Madelon E. The Forms of Language … … … … … … … … |

5 |

Beard Robert. The Agenda of Morphology … … … … … … … … … … … |

21 |

Uhlenbeck Eugenius M. Productivity and Creativity … … … … … … … … |

44 |

Jackson Howard. Analyzing English … … … … … … … … … … … … … |

47 |

Isitt David. Crazic, Menty and Idiotal. An Inquiry into the Use of Suffixes |

|

-al, -ic, -ly, and -y in Modern English … … … … … … … … … … … … … |

55 |

Kastovsky Dieter. Lexical Fields and Word-Formation … … … … … … … |

69 |

Marchand Hans. A Set of Criteria for the Establishing of Derivational |

|

Relationship between Words Unmarked by Derivational Morphemes … … |

77 |

Marchand Hans. Expansion, Transposition, and Derivation … … … … … . |

87 |

Aronoff Mark. When Nouns Surface as Verbs … … … … … … … … … … |

94 |

Selkirk Elisabeth O. A General Theory of Word Structure … … … … … … |

160 |

Lieber Rochelle. Morphology and Lexical Semantics … … … … … … … … |

169 |

LIST OF THE BOOKS CITED … … … … … … … … … … … … … … |

184 |

3

P R E F A C E

This book continues the series of Readers in English linguistics compiled at Minsk State Linguistic University for advanced students of English. Its aim is to give students of English an ample opportunity to get acquainted with the latest developments in the field of derivational morphology, make them aware of new approaches and opinions in this domain, develop students‟ ability to analyse critically the problem and stimulate them in their own research of the central subsystem of the English language.

For this Reader we have selected extracts from works by prominent European and American scholars in the field of morphology which cannot be easily obtained in the libraries of Belarus. In compiling the Reader we tried to select and arrange the authentic texts in such a way as to focus the students‟ attention, first of all, on the fundamental questions of morphology, which emerge from current research on English word structure, and then on the analysis of different processes of word formation in English. Several general works which open the Reader introduce the students to the basic notions and categories of morphology such as “morpheme”, “diachronic and synchronic morphology”, “folk etymology”, “inflectional and derivational morphology”, “derivational analysis”, etc. Then follow the extracts centred on the ways in which new lexical items may be created in English, thus describing processes of affixation, compounding and conversion.

We also invite our students to take part in the discussion of topics within each theoretical framework and develop their creativity, effective thinking techniques and problem-solving strategies. To this end, we supply the Reader with problem questions which follow every extract and which can fulfill the function of a comprehension check

The reader is intended not only for beginners in linguistics, who take the course in modern English lexicology, but also for more advanced students and scholars who do scientific research within the framework of modern English word formation.

4

Madelon E. Heatherington*

THE FORMS OF LANGUAGE

There are many parallels between phonology, the study of the sounds of a language, and morphology, the study of the forms of a language. The specialized terminology belonging to each discipline is an example of such paralleling, as table 5.1 indicates. There is no equivalent in morphology of phonetics, for when we wish to represent the sounds of a morpheme, we simply use a phonetic transcription. But what is a morpheme?

Table 5.1

Comparison of Terms in Phonology and Morphology

Study of |

phonology |

morphology |

|

|

|

Smallest Unit |

phoneme |

morpheme |

|

|

|

Variant |

allophone |

allomorph |

|

|

|

Actual Speech |

phone |

morph |

|

|

|

Transcription |

phonemic symbols / / |

morphemic symbols { } |

|

phonetic symbols [ ] |

|

|

|

|

The Morpheme

Let us first state what a morpheme is not: it is not a word, nor is it a syllable. Like the phoneme, the morpheme is frequently an abstraction, covering a range of possible variant forms (or allomorphs). But here, the abstraction is a unit of meaning, not a unit of sound: a morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in language.

Lexical and syntactic meaning. Immediately, however, we encounter trouble with the word “meaning”, which itself has many meanings. We shall examine the question of meaning in much more detail in chapter 9, but here let us stipulate that there are two basic kinds of morphological meaning: lexical, or semantic, and syntactic, or structural.

* Heatherington M.E. The Forms of Language // How Language Works. Winthrop Publishers Inc: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1980. P.50–64.

5

Lexical meaning. Lexical, or semantic, meaning is the type we ordinarily intend when we use the word “meaning”. Lexical meaning has a sense of content or reference about it; morphemes having lexical meaning are listed in dictionaries or thesauruses. Lexical meaning is then further divided into denotative meaning (ordinary usage, common, widespread) and connotative meaning (private or localized, not widespread). Thus, the usual lexical denotation of “apple” is: a red, yellow, or green fruit from the tree Pyrus malus. But the connotations may range all the way from pleasant (tastes good, supposedly keeps the doctor away) to unpleasant (symbol of strife, temptation, destruction). A morpheme that has more lexical than syntactic meaning is called a lexical morpheme.

Syntactic meaning. The other principal kind of meaning, syntactic, has less to do with content or reference and more to do with what we might call internal traffic directing. A morpheme that has syntactic meaning – a syntactic, or structural, morpheme – tends to direct other, more lexical morphemes, to signal relationships within a syntactic unit, to indicate what is subject and what is predicate, for instance.

Frequently, a syntactic morpheme is attached to a lexical one, in which case the attachment is called an inflection. The plural allomorphs are inflections, as are the tense markers, possession markers, and comparison markers. Such inflections as these do not have much lexical meaning themselves; the {ed} that signals the past tense in English does not have the content-meaning of a lexical morpheme like the word “apple”. But the inflections are necessary to show how one lexical morpheme is related to another, as in the phrase “John‟s book”, where the possessive inflection {'s}1 indicates that the book belongs to John. Similarly, tense signals a relationship: the word “pour”, which lacks an inflection, indicates action going on right now, in the present, whereas the word “poured”, composed of the lexical morpheme {pour} plus the inflection {ed}, signals a condition that has already occurred in the past. The relationship here is of time rather than of

1 Strictly speaking, the apostrophe (‟) is not morphemic, bur appears here because the word “John‟s” is written rather than spoken. The possessive morpheme actually is {s}, pronounced [z].

6

possession. Just as frequently, however, a syntactic morpheme is not attached to a lexical one, but occurs alone. Separate forms that primarily serve a syntactic rather than a lexical function are called function words, or sometimes operators.

Examples of such words include “and”, “there”, “because”, “or”, “but”, “so”, “than”. Like inflections, these words are low in lexical meaning but high in trafficdirecting or relationship-signaling function. The operator {and}, for example, primarily serves to connect two or more lexical words in a way that shows the two to have equivalent weight: “cats and dogs”, “red, white, and blue”. (Note that the connection is not “cats and dog” or “red, white, and cow”. Like other function words, “and” does not mean much, as we ordinarily use the word “mean”, but it does much in those phrases. If we changed “and” to “or” in each phrase, the relationship signaled among the words would be quite different.

Often it seems nearly impossible to distinguish lexical from syntactic meaning; there is much overlap between the two. Thus, almost any given morpheme may be classed as lexical or as syntactic, depending on how it is functioning in an utterance.

Morphology

Morphology, or the study of morphemes, can be most usefully subdivided into two types of analysis. One type, called synchronic morphology, investigates morphemes in a single dimension of time – any particular time, past or present. Essentially, synchronic morphology is a linear analysis, asking what are the lexical and syntactic components of words, and how do the components add, subtract, or rearrange themselves in various contexts.

Synchronic morphology is not concerned with the word‟s history in our language. If we bring in a historical dimension, however, and ask how a word‟s contemporary usage might be different from its first recorded usage, then we are moving into a field of historical linguistics called etymology, or diachronic (twodimensional time) morphology.

Anyone concerned with a full examination of a word‟s or a morpheme‟s meanings will, of course, pursue both a synchronic and a diachronic inquiry. A complete morphological analysis will require us to check the word‟s current

7

phonemic and morphemic structure as well as its past and present lexical meanings. Obviously, we can investigate historical alterations simultaneously with a synchronic look at the morphemic components.2 For purposes of discussion here, however, we will treat the two branches of morphology as separate entities.

Synchronic morphology. A synchronic investigation is asking, basically, what kinds of morphemes are combining in which sorts of ways to form a word. Often, a synchronic analysis of morphemes begins to spill over into an analysis of syntax, for morphology in general often becomes the shared territory of word meaning and sentence structure. We will try here, however, to keep our analysis of morphemes separate from syntax as much as possible.

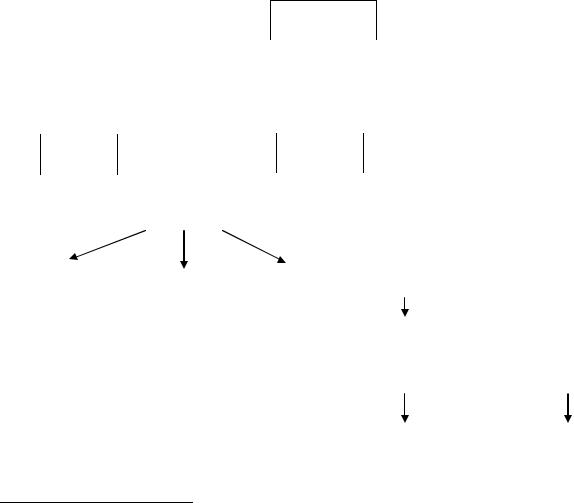

Figure 5.1

Binary Classification in Synchronic Morphology

morpheme

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

lexical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

syntactic |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

free |

|

|

|

|

|

|

bound |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

base |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

affix |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{rat} |

|

{or} |

{gen} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

prefix |

|

|

|

|

|

suffix |

|

||||||||||||||

lexical |

|

syntactic |

lexical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

free |

|

free |

bound |

|

{un} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

base |

|

base |

base |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

inflectional |

|

|

|

|

|

derivational |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{ed} |

|

|

|

|

|

{tion} |

|||||

2 For example, the word “etymology” synchronically analyzed contains three morphemes {etumo}, {log}, and {y}. Diachronically, the word comes from the Greek etumos, true or real and logy, study of. The etymological implication, therefore, is that only the original meanings of words are the true or real ones.

8

To begin such a synchronic investigation, we must first discover in what ways morphemes can be synchronically classified. Most useful may be three binary terms, three sets of two words nearly opposite in meaning. One term from each set can be applied to each morpheme as we encounter it (figure 5.1). Each morpheme should be describable by one, but not the other, of the words in each binary set. We have already mentioned the first pair of classifiers: lexical-syntactic.

Nearly all words in the lexicon can be identified as either lexical or syntactic morphemes.

Free-bound. The second such binary set is free-bound. Morphemes can be classified as either free or bound, that is, either capable of standing by themselves, as words, or not capable of standing by themselves. A free morpheme can be either lexical, like the word {rat}, or syntactic, like the operator {or}. If the free morpheme is syntactic rather than lexical, other morphemes will not combine with it. Lexical morphemes, however, can combine with other morphemes or other words. For example, to the free lexical morpheme {rat}, we can add the bound allomorph {s}, producing the word “rats”, or the bound morpheme {ty}, producing

“ratty”, or another free morpheme {catch}, plus a bound one, {er}, producing “ratcatcher”.

Base-affix. The third useful binary set for synchronic analysis of morphemes is base-affix. A morpheme may be classified as a base or as an affix but not as both

– at least, not in the same word. (Like the other terms in the two previous binary sets, “base” and “affix” are relational classifications rather than pure opposites. It is possible for the same morpheme to be free in one use and bound in another, or lexical in one case and syntactic in another.) A base – sometimes called a root – is a morpheme to which other morphemes are attached. The attaching morphemes are called the affixes.

Bases are morphemes that lexically, rather than syntactically, dominate other morphemes. Bases always have more lexical than syntactic meaning but bases are not always free. There are many bound bases in English as well as free bases. An example of a bound base is {gen}, a morpheme that has more lexical than

9