- •Table of Contents

- •Foreword

- •Chapter 1. A Quick Walk Through

- •Workfile: The Basic EViews Document

- •Viewing an individual series

- •Looking at different samples

- •Generating a new series

- •Looking at a pair of series together

- •Estimating your first regression in EViews

- •Saving your work

- •Forecasting

- •What’s Ahead

- •Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

- •The Structure of Data and the Structure of a Workfile

- •Creating a New Workfile

- •Deconstructing the Workfile

- •Time to Type

- •Identity Noncrisis

- •Dated Series

- •The Import Business

- •Adding Data To An Existing Workfile—Or, Being Rectangular Doesn’t Mean Being Inflexible

- •Among the Missing

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Having A Good Time With Your Date

- •Chapter 3. Getting the Most from Least Squares

- •A First Regression

- •The Really Important Regression Results

- •The Pretty Important (But Not So Important As the Last Section’s) Regression Results

- •A Multiple Regression Is Simple Too

- •Hypothesis Testing

- •Representing

- •What’s Left After You’ve Gotten the Most Out of Least Squares

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 4. Data—The Transformational Experience

- •Your Basic Elementary Algebra

- •Simple Sample Says

- •Data Types Plain and Fancy

- •Numbers and Letters

- •Can We Have A Date?

- •What Are Your Values?

- •Relative Exotica

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 5. Picture This!

- •A Simple Soup-To-Nuts Graphing Example

- •A Graphic Description of the Creative Process

- •Picture One Series

- •Group Graphics

- •Let’s Look At This From Another Angle

- •To Summarize

- •Categorical Graphs

- •Togetherness of the Second Sort

- •Quick Review and Look Ahead

- •Chapter 6. Intimacy With Graphic Objects

- •To Freeze Or Not To Freeze Redux

- •A Touch of Text

- •Shady Areas and No-Worry Lines

- •Templates for Success

- •Point Me The Way

- •Your Data Another Sorta Way

- •Give A Graph A Fair Break

- •Options, Options, Options

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 7. Look At Your Data

- •Sorting Things Out

- •Describing Series—Just The Facts Please

- •Describing Series—Picturing the Distribution

- •Tests On Series

- •Describing Groups—Just the Facts—Putting It Together

- •Chapter 8. Forecasting

- •Just Push the Forecast Button

- •Theory of Forecasting

- •Dynamic Versus Static Forecasting

- •Sample Forecast Samples

- •Facing the Unknown

- •Forecast Evaluation

- •Forecasting Beneath the Surface

- •Quick Review—Forecasting

- •Chapter 9. Page After Page After Page

- •Pages Are Easy To Reach

- •Creating New Pages

- •Renaming, Deleting, and Saving Pages

- •Multi-Page Workfiles—The Most Basic Motivation

- •Multiple Frequencies—Multiple Pages

- •Links—The Live Connection

- •Unlinking

- •Have A Match?

- •Matching When The Identifiers Are Really Different

- •Contracted Data

- •Expanded Data

- •Having Contractions

- •Two Hints and A GotchYa

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 10. Prelude to Panel and Pool

- •Pooled or Paneled Population

- •Nuances

- •So What Are the Benefits of Using Pools and Panels?

- •Quick (P)review

- •Chapter 11. Panel—What’s My Line?

- •What’s So Nifty About Panel Data?

- •Setting Up Panel Data

- •Panel Estimation

- •Pretty Panel Pictures

- •More Panel Estimation Techniques

- •One Dimensional Two-Dimensional Panels

- •Fixed Effects With and Without the Social Contrivance of Panel Structure

- •Quick Review—Panel

- •Chapter 12. Everyone Into the Pool

- •Getting Your Feet Wet

- •Playing in the Pool—Data

- •Getting Out of the Pool

- •More Pool Estimation

- •Getting Data In and Out of the Pool

- •Quick Review—Pools

- •Chapter 13. Serial Correlation—Friend or Foe?

- •Visual Checks

- •Testing for Serial Correlation

- •More General Patterns of Serial Correlation

- •Correcting for Serial Correlation

- •Forecasting

- •ARMA and ARIMA Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 14. A Taste of Advanced Estimation

- •Weighted Least Squares

- •Heteroskedasticity

- •Nonlinear Least Squares

- •Generalized Method of Moments

- •Limited Dependent Variables

- •ARCH, etc.

- •Maximum Likelihood—Rolling Your Own

- •System Estimation

- •Vector Autoregressions—VAR

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 15. Super Models

- •Your First Homework—Bam, Taken Up A Notch!

- •Looking At Model Solutions

- •More Model Information

- •Your Second Homework

- •Simulating VARs

- •Rich Super Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 16. Get With the Program

- •I Want To Do It Over and Over Again

- •You Want To Have An Argument

- •Program Variables

- •Loopy

- •Other Program Controls

- •A Rolling Example

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Sample Programs

- •Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

- •How Much Data Can EViews Handle?

- •How Long Does It Take To Compute An Estimate?

- •Freeze!

- •A Comment On Tables

- •Saving Tables and Almost Tables

- •Saving Graphs and Almost Graphs

- •Unsubtle Redirection

- •Objects and Commands

- •Workfile Backups

- •Updates—A Small Thing

- •Updates—A Big Thing

- •Ready To Take A Break?

- •Help!

- •Odd Ending

- •Chapter 18. Optional Ending

- •Required Options

- •Option-al Recommendations

- •More Detailed Options

- •Window Behavior

- •Font Options

- •Frequency Conversion

- •Alpha Truncation

- •Spreadsheet Defaults

- •Workfile Storage Defaults

- •Estimation Defaults

- •File Locations

- •Graphics Defaults

- •Quick Review

- •Index

- •Symbols

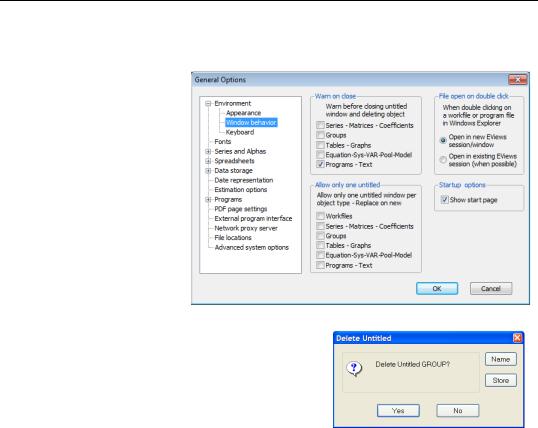

Window Behavior—407

Window Behavior

When EViews opens a new window, the window title is “Untitled”— unless you’ve explicitly given a name. Named objects are stored in the workfile; untitled objects aren’t. Commands like ls and show create untitled objects. So does freezing an object. If you do a lot of exploring, you’ll create many such untitled objects.

Unchecking Warn on close lets you close throwaways without having to deal with a delete confirmation dialog. On the other hand, once in a while you’ll delete something you meant to name and save.

As suggested earlier, you’ll probably want to

uncheck most of the options in Allow only one untitled. Doing so lets you type a sequence of ls commands, for example, without having to close windows between commands. The downside is that the screen can get awfully cluttered with accumulated untitled windows.

Keyboard Focus

The radio button Keyboard focus directs whether typed characters are “sent” by default to the command pane or to the currently active window. Most people leave this one alone, but if you find that you’re persistently typing in the command pane when you meant to be editing another window, try switching this button and see if the results are more in line with what your fingers intended.

408—Chapter 18. Optional Ending

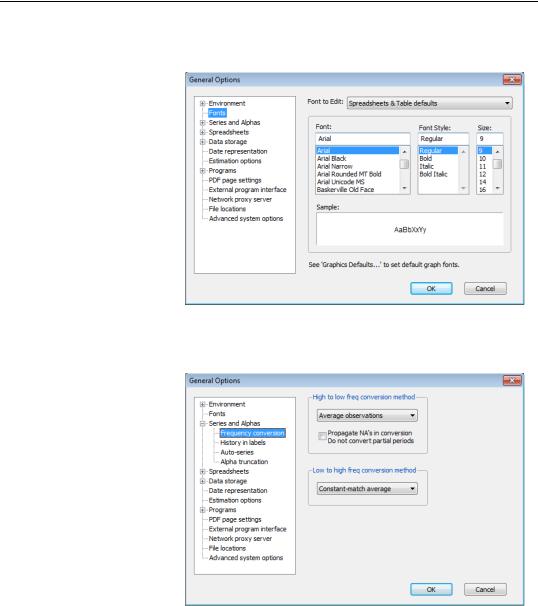

Font Options

The Fonts dialog controls default fonts in the workfile display, in spreadsheets, and in tables. Font selection is an issue about what looks good to you, so turn on whatever turns you on.

Frequency Conversion

The Series and

Alphas/Frequency conversion dialog lets you reset the default frequency conversions. Usually there’s a way to control the conversion method used for individual conversions. Sometimes—copy-and- paste, for example— there isn’t.

See Multiple Frequen- cies—Multiple Pages in Chapter 9, “Page After

Page After Page” for an extended discussion of frequency conversion.

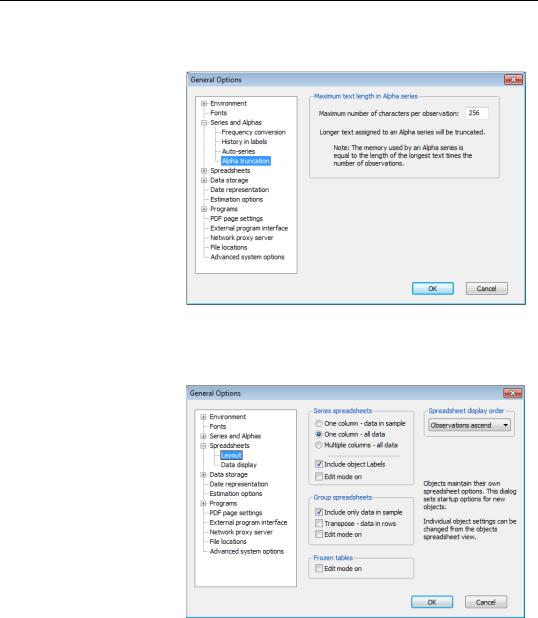

Alpha Truncation—409

Alpha Truncation

EViews sometimes truncates text in alpha series. You probably don’t want this to happen. Unless you’re storing large amounts of data in alpha series, increase the maximum number of characters so that nothing ever gets truncated. With modern computers, “large amounts of data” means on the order of 105 or 106 observations.

Spreadsheet Defaults

Aside from the comments in Option-al Recommendations above, there’s really nothing you need to change in the Spreadsheets defaults section. Looking at the Layout page, you may want to check one or more of the Edit mode on checkboxes. If you do, then the corresponding spreadsheets open with editing permitted. Leaving edit mode off gives you a

little protection against making an accidental change and economizes on screen space by suppressing the edit field in the spreadsheet. This is purely a matter of personal taste.

410—Chapter 18. Optional Ending

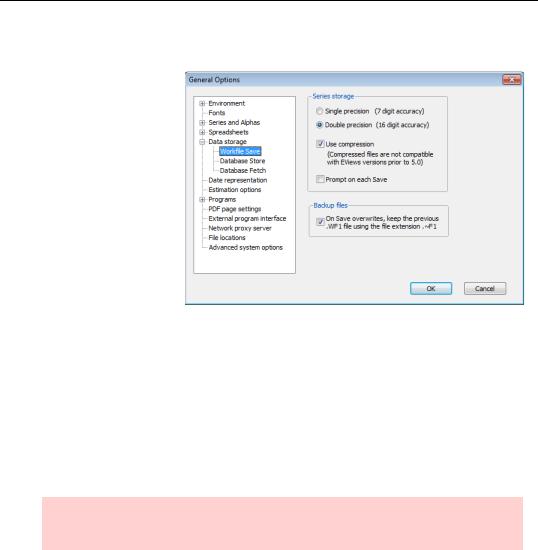

Workfile Storage Defaults

Back in the old days, computer storage was a scarce commodity. Data was often stored in “single precision,” offering about seven digits of accuracy in four bytes of storage. Today, data are usually represented in “double precision,” giving 16 digits of accuracy in eight bytes of storage. Since raw data aren’t likely to be accurate to more than seven digits,

single precision seems sufficient. However, numerical operations can introduce small errors. EViews holds all internal results in double precision for this reason. Using double precision when storing the workfile on the disk preserves this extra accuracy. Using single precision cuts file size in half, but causes some accuracy to be lost.

Internally, each observation in a series takes up eight bytes of storage. There’s no great reason you should care about this as either you have enough memory—in which case it doesn’t matter—or you don’t have enough memory—in which case your only option is to buy some more. And as a practical matter, unless you’re using millions of data points the issue will never arise.

Hint: Workfile Save Options have no effect on the amount of RAM (internal storage) required. They’re just for disk storage.

Use compression tells EViews to squish the data before storing to disk. When much of the data takes only the values 0 or 1, which is quite common, disk file size can be reduced by nearly a factor of 64. This level of compression is unusual, but shrinkage of 90 percent happens regularly. Unlike use of single precision, compression does not cause any loss of accuracy.

The truth is that disk storage is so cheap that there’s no reason to try to conserve it. While disk storage itself is rarely a limiting factor, moving around large files is sometimes a nuisance. This is especially true if you need to email a workfile.