- •Table of Contents

- •Foreword

- •Chapter 1. A Quick Walk Through

- •Workfile: The Basic EViews Document

- •Viewing an individual series

- •Looking at different samples

- •Generating a new series

- •Looking at a pair of series together

- •Estimating your first regression in EViews

- •Saving your work

- •Forecasting

- •What’s Ahead

- •Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

- •The Structure of Data and the Structure of a Workfile

- •Creating a New Workfile

- •Deconstructing the Workfile

- •Time to Type

- •Identity Noncrisis

- •Dated Series

- •The Import Business

- •Adding Data To An Existing Workfile—Or, Being Rectangular Doesn’t Mean Being Inflexible

- •Among the Missing

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Having A Good Time With Your Date

- •Chapter 3. Getting the Most from Least Squares

- •A First Regression

- •The Really Important Regression Results

- •The Pretty Important (But Not So Important As the Last Section’s) Regression Results

- •A Multiple Regression Is Simple Too

- •Hypothesis Testing

- •Representing

- •What’s Left After You’ve Gotten the Most Out of Least Squares

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 4. Data—The Transformational Experience

- •Your Basic Elementary Algebra

- •Simple Sample Says

- •Data Types Plain and Fancy

- •Numbers and Letters

- •Can We Have A Date?

- •What Are Your Values?

- •Relative Exotica

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 5. Picture This!

- •A Simple Soup-To-Nuts Graphing Example

- •A Graphic Description of the Creative Process

- •Picture One Series

- •Group Graphics

- •Let’s Look At This From Another Angle

- •To Summarize

- •Categorical Graphs

- •Togetherness of the Second Sort

- •Quick Review and Look Ahead

- •Chapter 6. Intimacy With Graphic Objects

- •To Freeze Or Not To Freeze Redux

- •A Touch of Text

- •Shady Areas and No-Worry Lines

- •Templates for Success

- •Point Me The Way

- •Your Data Another Sorta Way

- •Give A Graph A Fair Break

- •Options, Options, Options

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 7. Look At Your Data

- •Sorting Things Out

- •Describing Series—Just The Facts Please

- •Describing Series—Picturing the Distribution

- •Tests On Series

- •Describing Groups—Just the Facts—Putting It Together

- •Chapter 8. Forecasting

- •Just Push the Forecast Button

- •Theory of Forecasting

- •Dynamic Versus Static Forecasting

- •Sample Forecast Samples

- •Facing the Unknown

- •Forecast Evaluation

- •Forecasting Beneath the Surface

- •Quick Review—Forecasting

- •Chapter 9. Page After Page After Page

- •Pages Are Easy To Reach

- •Creating New Pages

- •Renaming, Deleting, and Saving Pages

- •Multi-Page Workfiles—The Most Basic Motivation

- •Multiple Frequencies—Multiple Pages

- •Links—The Live Connection

- •Unlinking

- •Have A Match?

- •Matching When The Identifiers Are Really Different

- •Contracted Data

- •Expanded Data

- •Having Contractions

- •Two Hints and A GotchYa

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 10. Prelude to Panel and Pool

- •Pooled or Paneled Population

- •Nuances

- •So What Are the Benefits of Using Pools and Panels?

- •Quick (P)review

- •Chapter 11. Panel—What’s My Line?

- •What’s So Nifty About Panel Data?

- •Setting Up Panel Data

- •Panel Estimation

- •Pretty Panel Pictures

- •More Panel Estimation Techniques

- •One Dimensional Two-Dimensional Panels

- •Fixed Effects With and Without the Social Contrivance of Panel Structure

- •Quick Review—Panel

- •Chapter 12. Everyone Into the Pool

- •Getting Your Feet Wet

- •Playing in the Pool—Data

- •Getting Out of the Pool

- •More Pool Estimation

- •Getting Data In and Out of the Pool

- •Quick Review—Pools

- •Chapter 13. Serial Correlation—Friend or Foe?

- •Visual Checks

- •Testing for Serial Correlation

- •More General Patterns of Serial Correlation

- •Correcting for Serial Correlation

- •Forecasting

- •ARMA and ARIMA Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 14. A Taste of Advanced Estimation

- •Weighted Least Squares

- •Heteroskedasticity

- •Nonlinear Least Squares

- •Generalized Method of Moments

- •Limited Dependent Variables

- •ARCH, etc.

- •Maximum Likelihood—Rolling Your Own

- •System Estimation

- •Vector Autoregressions—VAR

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 15. Super Models

- •Your First Homework—Bam, Taken Up A Notch!

- •Looking At Model Solutions

- •More Model Information

- •Your Second Homework

- •Simulating VARs

- •Rich Super Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 16. Get With the Program

- •I Want To Do It Over and Over Again

- •You Want To Have An Argument

- •Program Variables

- •Loopy

- •Other Program Controls

- •A Rolling Example

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Sample Programs

- •Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

- •How Much Data Can EViews Handle?

- •How Long Does It Take To Compute An Estimate?

- •Freeze!

- •A Comment On Tables

- •Saving Tables and Almost Tables

- •Saving Graphs and Almost Graphs

- •Unsubtle Redirection

- •Objects and Commands

- •Workfile Backups

- •Updates—A Small Thing

- •Updates—A Big Thing

- •Ready To Take A Break?

- •Help!

- •Odd Ending

- •Chapter 18. Optional Ending

- •Required Options

- •Option-al Recommendations

- •More Detailed Options

- •Window Behavior

- •Font Options

- •Frequency Conversion

- •Alpha Truncation

- •Spreadsheet Defaults

- •Workfile Storage Defaults

- •Estimation Defaults

- •File Locations

- •Graphics Defaults

- •Quick Review

- •Index

- •Symbols

Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

An odds and ends chapter is a good spot for topics and tips that don’t quite fit anywhere else. You’ve heard of Frequently Asked Questions. Think of this chapter as Possibly Helpful Auxiliary Topics.

Daughter hint: Oh daddy, that’s so 90’s.

How Much Data Can EViews Handle?

EViews holds workfiles in internal memory, i.e., in RAM, as opposed to on disk. Eight bytes are used for each number, so storing a million data points (1,000 series with 1,000 observations each, for example) requires 8 megabytes.

Data capacity isn’t an issue unless you have truly massive data needs, perhaps processing public use samples from the U.S. Census or records from credit card transactions. Current versions of EViews for 32-bit machines do have an out-of-the box limit of 4 million observations per series. If you are working on a 64-bit machine, you will be limited to 120 million observations per series.

Hint: Student versions of EViews place limits on the amount of data that may be saved and omit some of EViews’ more advanced features.

How Long Does It Take To Compute An Estimate?

Probably not long enough for you to care about.

On the author’s somewhat antiquated PC, computing a linear regression with ten right-hand side variables and 100,000 observations takes roughly one eye-blink.

Nonlinear estimation can take longer. First, a single nonlinear estimation step, i.e., one iteration, can be the equivalent of computing hundreds of regressions. Second, there’s no limit on how many iterations may be required for a nonlinear search. EViews’ nonlinear algorithms are both fast and accurate, but hard problems can take a while.

Freeze!

EViews’ objects change as you edit data, change samples, reset options, etc. When you have table output that you want to make sure won’t change, click the  button to open a new window, disconnected from the object you’ve been working on—and therefore frozen.

button to open a new window, disconnected from the object you’ve been working on—and therefore frozen.

You’ve taken a snapshot. Nothing prevents you from editing the snapshot—that’s the stan-

394—Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

dard approach for customizing a table for example—but the frozen object won’t change unless you change it.

Hint: Any untitled EViews object will disappear when you close its window. If you want to keep something you’ve frozen, use the  button.

button.

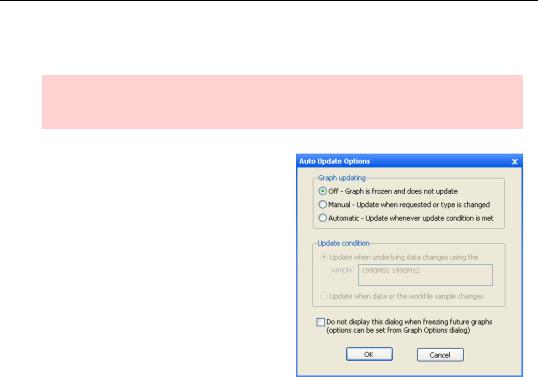

Frozen graphs offer more sophisticated behavior than frozen tables. When you have graphical output and click on the  button, EViews opens a dialog prompting you to choose Auto Update Options. Selecting Off means that the frozen graph acts exactly like a frozen table; it is a snapshot of the current graph that is disconnected from the original object. If you choose Manual or Automatic EViews will create a frozen (“chilled”) graph snapshot of the current graphical output that can update itself when the data in the original object changes.

button, EViews opens a dialog prompting you to choose Auto Update Options. Selecting Off means that the frozen graph acts exactly like a frozen table; it is a snapshot of the current graph that is disconnected from the original object. If you choose Manual or Automatic EViews will create a frozen (“chilled”) graph snapshot of the current graphical output that can update itself when the data in the original object changes.

Every frozen object is kept either as a table,

shown in the workfile window with the  icon, or a graph, shown with the

icon, or a graph, shown with the  icon. No matter how an object began life, once frozen you can adjust its appearance by using customization tools for tables or graphs.

icon. No matter how an object began life, once frozen you can adjust its appearance by using customization tools for tables or graphs.

A Comment On Tables—395

A Comment On Tables

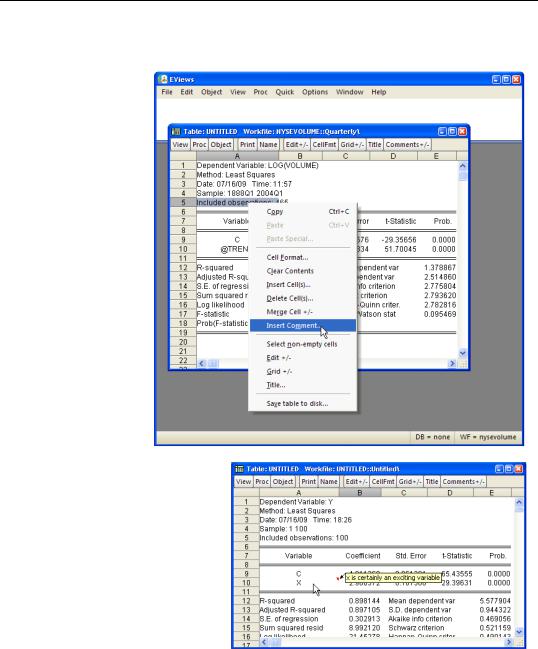

Every object has a label view providing a place to enter remarks about the object. Tables take this a step further. You can add a comment to any cell in a table. Select a cell and choose

Proc/Insert/Edit Comment… or right-click on a cell to bring up the context menu.

Cells with com-

ments are marked with little red triangles in the upper righthand corner. When the mouse passes over the cell, the comment is displayed in a note box.

396—Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

Saving Tables and Almost Tables

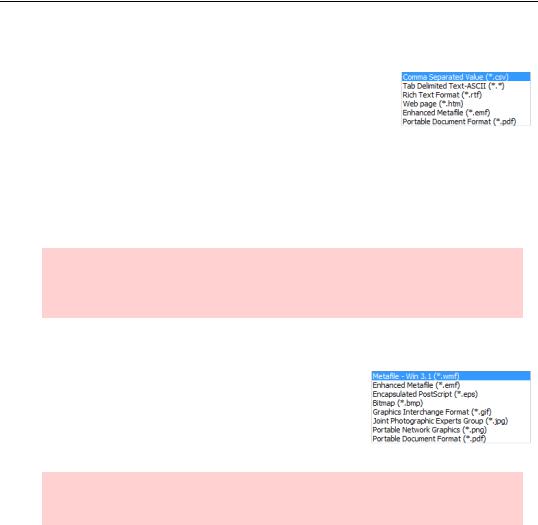

It’s nice to look at output on the screen, but eventually you’ll probably want to transfer some of your results into a word processor or other program. One fine method is copy-and-paste. You can also save any table as a disk file through Proc/Save table to disk… or the Save table to disk… context menu item when you

right-click in the table. Either way, you get a nice list of choices for the table format on disk.

If you’re planning on reading the table into a spreadsheet or database program, choose

Comma Separated Value or Tab Delimited Text-ASCII. If the table’s eventual destination is a word processor, you can use Rich Text Format to preserve the formatting that EViews has built into the table.

Hint: If you’re looking at a view of an object that would become a table if you froze it—regression output or a spreadsheet view of a series are examples—Save table to disk… shows up on the right-click menu even though it isn’t available from Proc.

Saving Graphs and Almost Graphs

Saving graphs works much like saving tables. In addition to using copy-and-paste to transfer your graph into another program, you can save any graph as a disk file through

Proc/Save graph to disk… or the Save graph to disk… context menu item when you right-click in the graph. Simply select one of the available graph disk formats.

Hint: If you’re looking at a view of an object that would become a graph if you froze it—Save graph to disk… shows up on the right-click menu.