- •Table of Contents

- •Foreword

- •Chapter 1. A Quick Walk Through

- •Workfile: The Basic EViews Document

- •Viewing an individual series

- •Looking at different samples

- •Generating a new series

- •Looking at a pair of series together

- •Estimating your first regression in EViews

- •Saving your work

- •Forecasting

- •What’s Ahead

- •Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

- •The Structure of Data and the Structure of a Workfile

- •Creating a New Workfile

- •Deconstructing the Workfile

- •Time to Type

- •Identity Noncrisis

- •Dated Series

- •The Import Business

- •Adding Data To An Existing Workfile—Or, Being Rectangular Doesn’t Mean Being Inflexible

- •Among the Missing

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Having A Good Time With Your Date

- •Chapter 3. Getting the Most from Least Squares

- •A First Regression

- •The Really Important Regression Results

- •The Pretty Important (But Not So Important As the Last Section’s) Regression Results

- •A Multiple Regression Is Simple Too

- •Hypothesis Testing

- •Representing

- •What’s Left After You’ve Gotten the Most Out of Least Squares

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 4. Data—The Transformational Experience

- •Your Basic Elementary Algebra

- •Simple Sample Says

- •Data Types Plain and Fancy

- •Numbers and Letters

- •Can We Have A Date?

- •What Are Your Values?

- •Relative Exotica

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 5. Picture This!

- •A Simple Soup-To-Nuts Graphing Example

- •A Graphic Description of the Creative Process

- •Picture One Series

- •Group Graphics

- •Let’s Look At This From Another Angle

- •To Summarize

- •Categorical Graphs

- •Togetherness of the Second Sort

- •Quick Review and Look Ahead

- •Chapter 6. Intimacy With Graphic Objects

- •To Freeze Or Not To Freeze Redux

- •A Touch of Text

- •Shady Areas and No-Worry Lines

- •Templates for Success

- •Point Me The Way

- •Your Data Another Sorta Way

- •Give A Graph A Fair Break

- •Options, Options, Options

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 7. Look At Your Data

- •Sorting Things Out

- •Describing Series—Just The Facts Please

- •Describing Series—Picturing the Distribution

- •Tests On Series

- •Describing Groups—Just the Facts—Putting It Together

- •Chapter 8. Forecasting

- •Just Push the Forecast Button

- •Theory of Forecasting

- •Dynamic Versus Static Forecasting

- •Sample Forecast Samples

- •Facing the Unknown

- •Forecast Evaluation

- •Forecasting Beneath the Surface

- •Quick Review—Forecasting

- •Chapter 9. Page After Page After Page

- •Pages Are Easy To Reach

- •Creating New Pages

- •Renaming, Deleting, and Saving Pages

- •Multi-Page Workfiles—The Most Basic Motivation

- •Multiple Frequencies—Multiple Pages

- •Links—The Live Connection

- •Unlinking

- •Have A Match?

- •Matching When The Identifiers Are Really Different

- •Contracted Data

- •Expanded Data

- •Having Contractions

- •Two Hints and A GotchYa

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 10. Prelude to Panel and Pool

- •Pooled or Paneled Population

- •Nuances

- •So What Are the Benefits of Using Pools and Panels?

- •Quick (P)review

- •Chapter 11. Panel—What’s My Line?

- •What’s So Nifty About Panel Data?

- •Setting Up Panel Data

- •Panel Estimation

- •Pretty Panel Pictures

- •More Panel Estimation Techniques

- •One Dimensional Two-Dimensional Panels

- •Fixed Effects With and Without the Social Contrivance of Panel Structure

- •Quick Review—Panel

- •Chapter 12. Everyone Into the Pool

- •Getting Your Feet Wet

- •Playing in the Pool—Data

- •Getting Out of the Pool

- •More Pool Estimation

- •Getting Data In and Out of the Pool

- •Quick Review—Pools

- •Chapter 13. Serial Correlation—Friend or Foe?

- •Visual Checks

- •Testing for Serial Correlation

- •More General Patterns of Serial Correlation

- •Correcting for Serial Correlation

- •Forecasting

- •ARMA and ARIMA Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 14. A Taste of Advanced Estimation

- •Weighted Least Squares

- •Heteroskedasticity

- •Nonlinear Least Squares

- •Generalized Method of Moments

- •Limited Dependent Variables

- •ARCH, etc.

- •Maximum Likelihood—Rolling Your Own

- •System Estimation

- •Vector Autoregressions—VAR

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 15. Super Models

- •Your First Homework—Bam, Taken Up A Notch!

- •Looking At Model Solutions

- •More Model Information

- •Your Second Homework

- •Simulating VARs

- •Rich Super Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 16. Get With the Program

- •I Want To Do It Over and Over Again

- •You Want To Have An Argument

- •Program Variables

- •Loopy

- •Other Program Controls

- •A Rolling Example

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Sample Programs

- •Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

- •How Much Data Can EViews Handle?

- •How Long Does It Take To Compute An Estimate?

- •Freeze!

- •A Comment On Tables

- •Saving Tables and Almost Tables

- •Saving Graphs and Almost Graphs

- •Unsubtle Redirection

- •Objects and Commands

- •Workfile Backups

- •Updates—A Small Thing

- •Updates—A Big Thing

- •Ready To Take A Break?

- •Help!

- •Odd Ending

- •Chapter 18. Optional Ending

- •Required Options

- •Option-al Recommendations

- •More Detailed Options

- •Window Behavior

- •Font Options

- •Frequency Conversion

- •Alpha Truncation

- •Spreadsheet Defaults

- •Workfile Storage Defaults

- •Estimation Defaults

- •File Locations

- •Graphics Defaults

- •Quick Review

- •Index

- •Symbols

Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

When you embark on an econometric journey, your first step will be to bring your data into EViews. In this chapter we talk about a variety of methods for getting this journey started on the right foot.

Unlike the blank piece of paper that appears (metaphorically speaking) when you fire up a word processor or the empty spreadsheet provided by a spreadsheet program, the basic EViews document—the workfile—requires just a little bit of structuring information. We begin by talking about how to set up a workfile. Next we turn to manual entry, typing data by hand. While typing data is sometimes necessary, it’s awfully nice when we can just transfer the data in from another program. So a good part of the chapter is devoted to data import.

To get started, here’s an excerpt from the file “AcadSalaries.wf1”. This file, available on the EViews website, excerpts data from a September 1994 article in Academe, the journal of the American Association of University Professors. The data give information from a survey of salaries in a number of academic disciplines. The excerpt in Table 1: Academic Salary Data Excerpt shows average academic salaries and corresponding salaries outside of academics.

Table 1: Academic Salary Data Excerpt

OBS |

DISCIPLINE |

SALARY |

NONACADSAL |

|

|

|

|

1 |

Dentistry |

44,214 |

40,005 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

Medicine |

43,160 |

50,005 |

|

|

|

|

3 |

Law |

40,670 |

30,518 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

Agriculture |

36,879 |

31,063 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

Engineering |

35,694 |

35,133 |

|

|

|

|

6 |

Geology |

33,206 |

33,602 |

|

|

|

|

7 |

Chemistry |

33,069 |

32,489 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

Physics |

32,925 |

33,434 |

|

|

|

|

9 |

Life Sciences |

32,605 |

30,500 |

|

|

|

|

10 |

Economics |

32,179 |

37,052 |

|

|

|

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

|

|

|

28 |

Library Science |

23,658 |

15,980 |

24—Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

The Structure of Data and the Structure of a Workfile

Look at Table 1: Academic Salary Data Excerpt .

First thing to notice: data come arranged in rows and columns. Every column holds one series of data; for example, the values of SALARY for every discipline. Every row holds one observation; an example being the value of SALARY, NONACADSAL, and the name of the discipline for “dentistry.” When data come arranged in a neat rectangle, as it does here, statisticians call the arrangement a “data rectangle.”

Hint: When thinking of an econometric model, a data series is often just called a “variable.”

Second thing to notice: the observations (rows) come in order. In the column marked “obs” the observations are numbered 1, 2, 3, 4…28. The observation numbers are sometimes called, well, “observation numbers.” Sometimes the entire set of observation numbers is called an “identifier” or an “id series.” When appropriate, dates are used in place of plain numbers.

Hint: Series (columns) don’t have any inherent order, but observation numbers (rows) do. SALARY is neither before nor after DISCIPLINE in any important sense. In contrast, 2 really is the number after 1.

EViews needs to know how observations are numbered. When you set up a workfile, the first thing you need to do is tell EViews how the identifier of your data is structured: monthly, annual, just numbered 1, 2, 3, …, etc. Your second task is to tell EViews the range your observations take: January 1888 through January 2004, 1939 through 1944, 1 through 28, etc.

And that’s all you need to know.

Hint: Every variable in an EViews workfile shares a common identifier series. You can’t have one variable that’s measured in January, February, and March and a different variable that’s measured in the chocolate mixing bowl, the vanilla mixing bowl, and the mocha mixing bowl.

Subhint: Well, yes actually, you can. EViews has quite sophisticated capabilities for handling both mixed frequency data and panel data. These are covered later in the book.

Creating a New Workfile—25

Creating a New Workfile

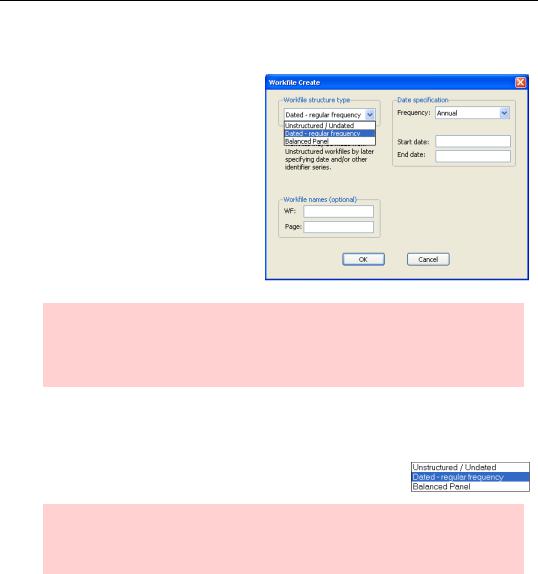

Open EViews and use the menu to choose File/New/Workfile… The Workfile Create dialog pops up.

Hint: Alternatively, you can type

wfcreate

in the command pane to bring up the same dialog.

You’ll notice in the dialog that EViews defaults to “Dated – regular frequency” and “Annual.” However, the data shown in Table 1: Academic Salary Data Excerpt are just numbered sequentially. They aren’t dated.

Choosing the Workfile structure type dropdown menu offers three choices:

Hint: Changing the type of workfile structure can be mildly inconvenient, so it pays to think a little about this decision. In contrast, simply increasing or decreasing the range of observations in the workfile is quite easy.

Our data are Unstructured/Undated. Select this option. Later in this chapter we’ll discuss Dated – regular frequency. (Balanced Panel is deferred to Chapter 11, “Panel—What’s My Line?.”)

26—Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

Hint: Alternatively, we can enter

wfcreate u

in the command pane.

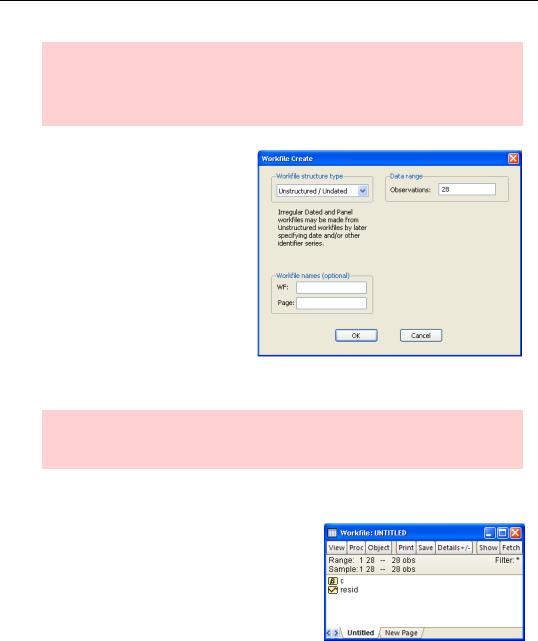

Unstructured/Undated instructs EViews to number the observations from 1 through however-many-obser- vations-you-have. In our example we have 28 observations. Enter “28” in the field marked “Observations:” If you’d like to give your workfile a name you can enter the name in the “WF:” field at the lower right. You can also name the workfile when you save it, so giving a name now or later is purely a matter of personal preference.

Hit  and the workfile is created for you.

and the workfile is created for you.

Hint: If you like, the workfile can be created with the single command

wfcreate u 28

Deconstructing the Workfile

There’s no data yet, but let’s dissect what EViews starts you off with. The initial workfile window looks something like the picture to the right.

The title bar shows the name of the workfile. Since we didn’t enter a name for the workfile in the dialog, EViews uses “UNTITLED” in the title bar.

The workfile window has buttons at the top and

tabs at the bottom. The buttons provide menus linked to each EViews window type. The tabs mark pages, essentially workfiles within a workfile. We’ll come back to pages in Chapter 9, “Page After Page After Page”; they’re particularly useful for holding sets of data with different indices.