- •Table of Contents

- •Foreword

- •Chapter 1. A Quick Walk Through

- •Workfile: The Basic EViews Document

- •Viewing an individual series

- •Looking at different samples

- •Generating a new series

- •Looking at a pair of series together

- •Estimating your first regression in EViews

- •Saving your work

- •Forecasting

- •What’s Ahead

- •Chapter 2. EViews—Meet Data

- •The Structure of Data and the Structure of a Workfile

- •Creating a New Workfile

- •Deconstructing the Workfile

- •Time to Type

- •Identity Noncrisis

- •Dated Series

- •The Import Business

- •Adding Data To An Existing Workfile—Or, Being Rectangular Doesn’t Mean Being Inflexible

- •Among the Missing

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Having A Good Time With Your Date

- •Chapter 3. Getting the Most from Least Squares

- •A First Regression

- •The Really Important Regression Results

- •The Pretty Important (But Not So Important As the Last Section’s) Regression Results

- •A Multiple Regression Is Simple Too

- •Hypothesis Testing

- •Representing

- •What’s Left After You’ve Gotten the Most Out of Least Squares

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 4. Data—The Transformational Experience

- •Your Basic Elementary Algebra

- •Simple Sample Says

- •Data Types Plain and Fancy

- •Numbers and Letters

- •Can We Have A Date?

- •What Are Your Values?

- •Relative Exotica

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 5. Picture This!

- •A Simple Soup-To-Nuts Graphing Example

- •A Graphic Description of the Creative Process

- •Picture One Series

- •Group Graphics

- •Let’s Look At This From Another Angle

- •To Summarize

- •Categorical Graphs

- •Togetherness of the Second Sort

- •Quick Review and Look Ahead

- •Chapter 6. Intimacy With Graphic Objects

- •To Freeze Or Not To Freeze Redux

- •A Touch of Text

- •Shady Areas and No-Worry Lines

- •Templates for Success

- •Point Me The Way

- •Your Data Another Sorta Way

- •Give A Graph A Fair Break

- •Options, Options, Options

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 7. Look At Your Data

- •Sorting Things Out

- •Describing Series—Just The Facts Please

- •Describing Series—Picturing the Distribution

- •Tests On Series

- •Describing Groups—Just the Facts—Putting It Together

- •Chapter 8. Forecasting

- •Just Push the Forecast Button

- •Theory of Forecasting

- •Dynamic Versus Static Forecasting

- •Sample Forecast Samples

- •Facing the Unknown

- •Forecast Evaluation

- •Forecasting Beneath the Surface

- •Quick Review—Forecasting

- •Chapter 9. Page After Page After Page

- •Pages Are Easy To Reach

- •Creating New Pages

- •Renaming, Deleting, and Saving Pages

- •Multi-Page Workfiles—The Most Basic Motivation

- •Multiple Frequencies—Multiple Pages

- •Links—The Live Connection

- •Unlinking

- •Have A Match?

- •Matching When The Identifiers Are Really Different

- •Contracted Data

- •Expanded Data

- •Having Contractions

- •Two Hints and A GotchYa

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 10. Prelude to Panel and Pool

- •Pooled or Paneled Population

- •Nuances

- •So What Are the Benefits of Using Pools and Panels?

- •Quick (P)review

- •Chapter 11. Panel—What’s My Line?

- •What’s So Nifty About Panel Data?

- •Setting Up Panel Data

- •Panel Estimation

- •Pretty Panel Pictures

- •More Panel Estimation Techniques

- •One Dimensional Two-Dimensional Panels

- •Fixed Effects With and Without the Social Contrivance of Panel Structure

- •Quick Review—Panel

- •Chapter 12. Everyone Into the Pool

- •Getting Your Feet Wet

- •Playing in the Pool—Data

- •Getting Out of the Pool

- •More Pool Estimation

- •Getting Data In and Out of the Pool

- •Quick Review—Pools

- •Chapter 13. Serial Correlation—Friend or Foe?

- •Visual Checks

- •Testing for Serial Correlation

- •More General Patterns of Serial Correlation

- •Correcting for Serial Correlation

- •Forecasting

- •ARMA and ARIMA Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 14. A Taste of Advanced Estimation

- •Weighted Least Squares

- •Heteroskedasticity

- •Nonlinear Least Squares

- •Generalized Method of Moments

- •Limited Dependent Variables

- •ARCH, etc.

- •Maximum Likelihood—Rolling Your Own

- •System Estimation

- •Vector Autoregressions—VAR

- •Quick Review?

- •Chapter 15. Super Models

- •Your First Homework—Bam, Taken Up A Notch!

- •Looking At Model Solutions

- •More Model Information

- •Your Second Homework

- •Simulating VARs

- •Rich Super Models

- •Quick Review

- •Chapter 16. Get With the Program

- •I Want To Do It Over and Over Again

- •You Want To Have An Argument

- •Program Variables

- •Loopy

- •Other Program Controls

- •A Rolling Example

- •Quick Review

- •Appendix: Sample Programs

- •Chapter 17. Odds and Ends

- •How Much Data Can EViews Handle?

- •How Long Does It Take To Compute An Estimate?

- •Freeze!

- •A Comment On Tables

- •Saving Tables and Almost Tables

- •Saving Graphs and Almost Graphs

- •Unsubtle Redirection

- •Objects and Commands

- •Workfile Backups

- •Updates—A Small Thing

- •Updates—A Big Thing

- •Ready To Take A Break?

- •Help!

- •Odd Ending

- •Chapter 18. Optional Ending

- •Required Options

- •Option-al Recommendations

- •More Detailed Options

- •Window Behavior

- •Font Options

- •Frequency Conversion

- •Alpha Truncation

- •Spreadsheet Defaults

- •Workfile Storage Defaults

- •Estimation Defaults

- •File Locations

- •Graphics Defaults

- •Quick Review

- •Index

- •Symbols

210—Chapter 7. Look At Your Data

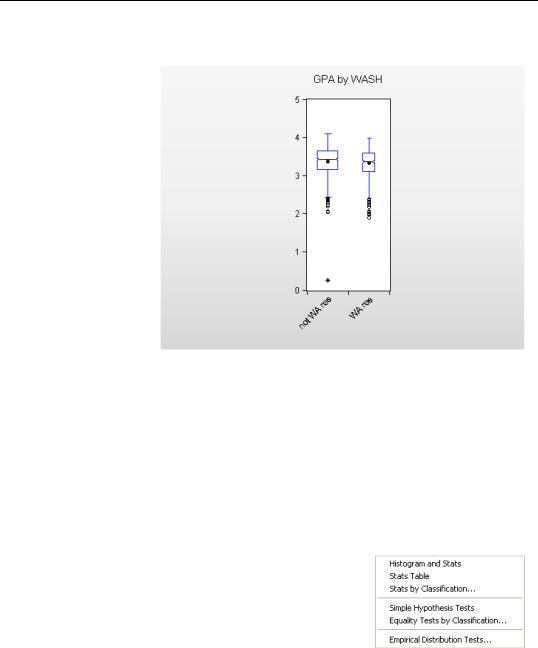

Boxplots By Categories

Boxplots give quick visual comparisons of different subpopulations. In this plot we’re again classifying GPA by Washington residence using the categorical graph tools. We also clicked the notched and proportional to observations radio buttons in the dialog. The distribution of grades is higher for non-

Washington residents, but the ranges for residents and non-residents mostly overlap.

Statistics don’t lie, but they can mislead. In this plot, the upper staple for non-residents is higher than the staple for residents. A little investigation shows that, while GPA is measured on a four point scale, one observation for a non-residents was recorded 4.1. Because some schools use something other than a four point scale, we don’t know if this GPA is an error or not. But we probably shouldn’t conclude anything about the difference between inand out-of-state applicants based on this one data point.

Tests On Series

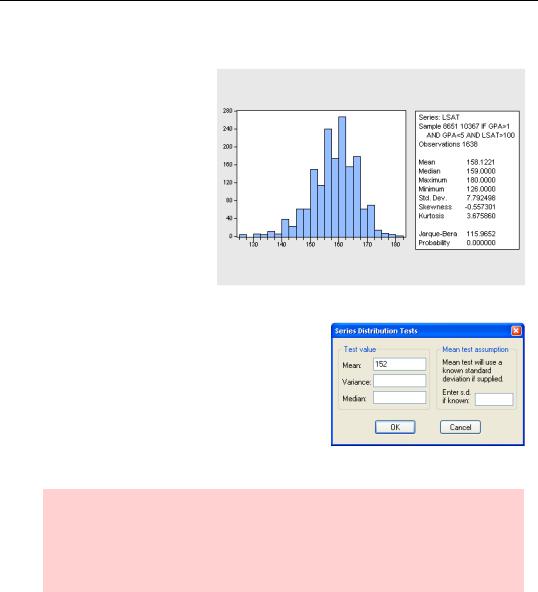

Up to this point, we’ve been looking at ways to summarize the data in a series. Now we move on to formal hypothesis tests. The tests corresponding to the descriptive statistics we’ve looked at are found under the Descriptive Statistics & Tests menu. As an example, having found the mean LSAT in our applicant pool, we might want to test whether it differs from the national average.

Tests On Series—211

Simple Hypothesis Tests

Nationally, the average LSAT score is about 152. Looking at the data for University of Washington applicants, we see their average was higher, just over 158. It would be interesting to know whether the difference is meaningful, or whether it’s a random statistical fluke.

Formally, we want to test the hypothesis that the mean University of Washington score equals 152 and ask whether there is sufficient evidence to reject this hypothesis. We will perform this test after setting the sample to include observations where the GPA is within normal bounds and the LSAT score exceeds 100. Choose Descriptive Statistics & Tests and Simple Hypothesis Tests and then enter the hypothesized mean in the Series Distribution Tests dialog.

Hint: If you’re only testing a mean, you don’t need to fill out any other fields. The Variance and Median fields are for hypothesis tests on the variance or median. In particular, don’t enter a previously estimated standard deviation in the Enter s.d. if known field. That’s only for the (unusual) case in which a standard deviation is known, rather than having been estimated.

212—Chapter 7. Look At Your Data

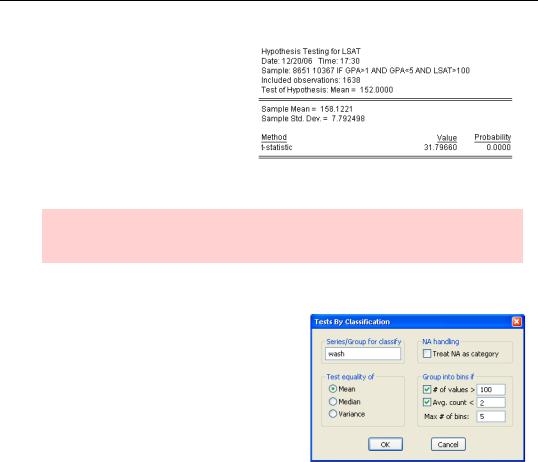

EViews conducts a standard t-test for this hypothesis, providing both the t- statistic and its associated p-value. In this case, the p-value tells us that if the true average LSAT in the applicant pool was 152, the probability of observing the mean LSAT found in our data, 158, is zero to four decimal places. Clearly, applicants to the Uni-

versity of Washington’s (very good) law school are better than the average LSAT taker.

Buzzword hint: We’d say that the average UW applicant LSAT is statistically significantly different from the average of all test takers.

Tests By Classification

We know from our work earlier in the chapter that out-of-state applicants have a slightly higher average GPA than do in-state applicants. Is the difference statistically significant? Open the GPA series and use the menu Equality Tests by Classification… to get to the Tests By Classification dialog. We’ve filled out the

Series/Group for classify field with the series WASH, since that’s the classifying variable of interest.

Tests On Series—213

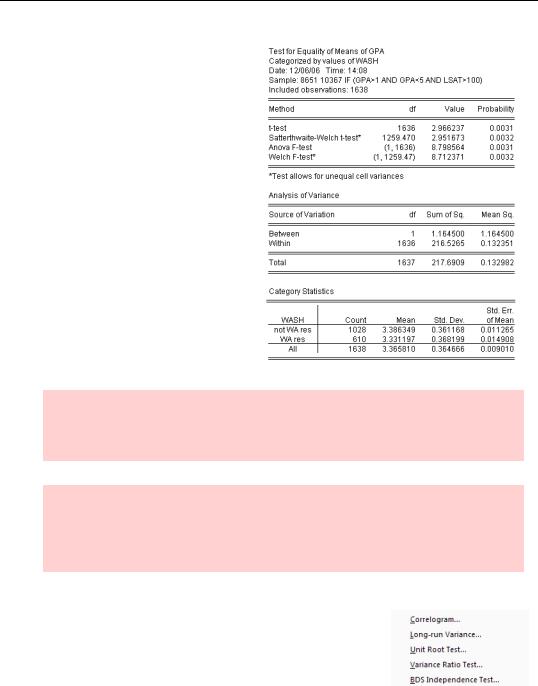

Since there are only two categories in this problem, in-state and out-, we need only look at the reported t-statis- tic and its associated p-value. If there were more than two categories, we would have to rely on the F-statistic; with exactly two categories, the F- is redundant with the t-.

While the difference between in-state and out-of-state GPAs is very small, statistically it’s highly significant.

Hint: Finding a difference that is statistically significant but very small demonstrates the maxim that with enough data you can accurately identify differences too small for anyone to care about.

Statistical hint: The basic Anova F-test for differences of means assumes that the subpopulations have equal variances. Most introductory statistics classes also teach the Satterthwaite and Welch tests that allow for different variances for different subpopulations.

Time series tests

Five tests of the time-series properties of a series appear in the View menu. Exploring these tests would take us too far afield for now, but Correlograms and Unit Root Tests will be discussed in Chapter 13, “Serial Correlation—Friend or Foe?”