- •1.1 TODO LIST

- •2. PROGRAMMABLE LOGIC CONTROLLERS

- •2.1 INTRODUCTION

- •2.1.1 Ladder Logic

- •2.1.2 Programming

- •2.1.3 PLC Connections

- •2.1.4 Ladder Logic Inputs

- •2.1.5 Ladder Logic Outputs

- •2.2 A CASE STUDY

- •2.3 SUMMARY

- •2.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •2.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •2.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •3. PLC HARDWARE

- •3.1 INTRODUCTION

- •3.2 INPUTS AND OUTPUTS

- •3.2.1 Inputs

- •3.2.2 Output Modules

- •3.3 RELAYS

- •3.4 A CASE STUDY

- •3.5 ELECTRICAL WIRING DIAGRAMS

- •3.5.1 JIC Wiring Symbols

- •3.6 SUMMARY

- •3.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •3.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •3.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •4. LOGICAL SENSORS

- •4.1 INTRODUCTION

- •4.2 SENSOR WIRING

- •4.2.1 Switches

- •4.2.2 Transistor Transistor Logic (TTL)

- •4.2.3 Sinking/Sourcing

- •4.2.4 Solid State Relays

- •4.3 PRESENCE DETECTION

- •4.3.1 Contact Switches

- •4.3.2 Reed Switches

- •4.3.3 Optical (Photoelectric) Sensors

- •4.3.4 Capacitive Sensors

- •4.3.5 Inductive Sensors

- •4.3.6 Ultrasonic

- •4.3.7 Hall Effect

- •4.3.8 Fluid Flow

- •4.4 SUMMARY

- •4.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •4.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •4.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •5. LOGICAL ACTUATORS

- •5.1 INTRODUCTION

- •5.2 SOLENOIDS

- •5.3 VALVES

- •5.4 CYLINDERS

- •5.5 HYDRAULICS

- •5.6 PNEUMATICS

- •5.7 MOTORS

- •5.8 COMPUTERS

- •5.9 OTHERS

- •5.10 SUMMARY

- •5.11 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •5.12 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •5.13 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •6. BOOLEAN LOGIC DESIGN

- •6.1 INTRODUCTION

- •6.2 BOOLEAN ALGEBRA

- •6.3 LOGIC DESIGN

- •6.3.1 Boolean Algebra Techniques

- •6.4 COMMON LOGIC FORMS

- •6.4.1 Complex Gate Forms

- •6.4.2 Multiplexers

- •6.5 SIMPLE DESIGN CASES

- •6.5.1 Basic Logic Functions

- •6.5.2 Car Safety System

- •6.5.3 Motor Forward/Reverse

- •6.5.4 A Burglar Alarm

- •6.6 SUMMARY

- •6.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •6.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •6.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •7. KARNAUGH MAPS

- •7.1 INTRODUCTION

- •7.2 SUMMARY

- •7.3 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •7.4 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •7.5 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •8. PLC OPERATION

- •8.1 INTRODUCTION

- •8.2 OPERATION SEQUENCE

- •8.2.1 The Input and Output Scans

- •8.2.2 The Logic Scan

- •8.3 PLC STATUS

- •8.4 MEMORY TYPES

- •8.5 SOFTWARE BASED PLCS

- •8.6 SUMMARY

- •8.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •8.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •8.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •9. LATCHES, TIMERS, COUNTERS AND MORE

- •9.1 INTRODUCTION

- •9.2 LATCHES

- •9.3 TIMERS

- •9.4 COUNTERS

- •9.5 MASTER CONTROL RELAYS (MCRs)

- •9.6 INTERNAL RELAYS

- •9.7 DESIGN CASES

- •9.7.1 Basic Counters And Timers

- •9.7.2 More Timers And Counters

- •9.7.3 Deadman Switch

- •9.7.4 Conveyor

- •9.7.5 Accept/Reject Sorting

- •9.7.6 Shear Press

- •9.8 SUMMARY

- •9.9 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •9.10 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •9.11 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •10. STRUCTURED LOGIC DESIGN

- •10.1 INTRODUCTION

- •10.2 PROCESS SEQUENCE BITS

- •10.3 TIMING DIAGRAMS

- •10.4 DESIGN CASES

- •10.5 SUMMARY

- •10.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •10.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •10.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •11. FLOWCHART BASED DESIGN

- •11.1 INTRODUCTION

- •11.2 BLOCK LOGIC

- •11.3 SEQUENCE BITS

- •11.4 SUMMARY

- •11.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •11.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •11.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •12. STATE BASED DESIGN

- •12.1 INTRODUCTION

- •12.1.1 State Diagram Example

- •12.1.2 Conversion to Ladder Logic

- •12.1.2.1 - Block Logic Conversion

- •12.1.2.2 - State Equations

- •12.1.2.3 - State-Transition Equations

- •12.2 SUMMARY

- •12.3 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •12.4 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •12.5 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •13. NUMBERS AND DATA

- •13.1 INTRODUCTION

- •13.2 NUMERICAL VALUES

- •13.2.1 Binary

- •13.2.1.1 - Boolean Operations

- •13.2.1.2 - Binary Mathematics

- •13.2.2 Other Base Number Systems

- •13.2.3 BCD (Binary Coded Decimal)

- •13.3 DATA CHARACTERIZATION

- •13.3.1 ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange)

- •13.3.2 Parity

- •13.3.3 Checksums

- •13.3.4 Gray Code

- •13.4 SUMMARY

- •13.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •13.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •13.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •14. PLC MEMORY

- •14.1 INTRODUCTION

- •14.2 MEMORY ADDRESSES

- •14.3 PROGRAM FILES

- •14.4 DATA FILES

- •14.4.1 User Bit Memory

- •14.4.2 Timer Counter Memory

- •14.4.3 PLC Status Bits (for PLC-5s and Micrologix)

- •14.4.4 User Function Control Memory

- •14.4.5 Integer Memory

- •14.4.6 Floating Point Memory

- •14.5 SUMMARY

- •14.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •14.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •14.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •15. LADDER LOGIC FUNCTIONS

- •15.1 INTRODUCTION

- •15.2 DATA HANDLING

- •15.2.1 Move Functions

- •15.2.2 Mathematical Functions

- •15.2.3 Conversions

- •15.2.4 Array Data Functions

- •15.2.4.1 - Statistics

- •15.2.4.2 - Block Operations

- •15.3 LOGICAL FUNCTIONS

- •15.3.1 Comparison of Values

- •15.3.2 Boolean Functions

- •15.4 DESIGN CASES

- •15.4.1 Simple Calculation

- •15.4.2 For-Next

- •15.4.3 Series Calculation

- •15.4.4 Flashing Lights

- •15.5 SUMMARY

- •15.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •15.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •15.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •16. ADVANCED LADDER LOGIC FUNCTIONS

- •16.1 INTRODUCTION

- •16.2 LIST FUNCTIONS

- •16.2.1 Shift Registers

- •16.2.2 Stacks

- •16.2.3 Sequencers

- •16.3 PROGRAM CONTROL

- •16.3.1 Branching and Looping

- •16.3.2 Fault Detection and Interrupts

- •16.4 INPUT AND OUTPUT FUNCTIONS

- •16.4.1 Immediate I/O Instructions

- •16.4.2 Block Transfer Functions

- •16.5 DESIGN TECHNIQUES

- •16.5.1 State Diagrams

- •16.6 DESIGN CASES

- •16.6.1 If-Then

- •16.6.2 Traffic Light

- •16.7 SUMMARY

- •16.8 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •16.9 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •16.10 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •17. OPEN CONTROLLERS

- •17.1 INTRODUCTION

- •17.3 OPEN ARCHITECTURE CONTROLLERS

- •17.4 SUMMARY

- •17.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •17.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •17.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •18. INSTRUCTION LIST PROGRAMMING

- •18.1 INTRODUCTION

- •18.2 THE IEC 61131 VERSION

- •18.3 THE ALLEN-BRADLEY VERSION

- •18.4 SUMMARY

- •18.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •18.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •18.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •19. STRUCTURED TEXT PROGRAMMING

- •19.1 INTRODUCTION

- •19.2 THE LANGUAGE

- •19.3 SUMMARY

- •19.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •19.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •19.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •20. SEQUENTIAL FUNCTION CHARTS

- •20.1 INTRODUCTION

- •20.2 A COMPARISON OF METHODS

- •20.3 SUMMARY

- •20.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •20.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •20.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •21. FUNCTION BLOCK PROGRAMMING

- •21.1 INTRODUCTION

- •21.2 CREATING FUNCTION BLOCKS

- •21.3 DESIGN CASE

- •21.4 SUMMARY

- •21.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •21.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •21.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •22. ANALOG INPUTS AND OUTPUTS

- •22.1 INTRODUCTION

- •22.2 ANALOG INPUTS

- •22.2.1 Analog Inputs With a PLC

- •22.3 ANALOG OUTPUTS

- •22.3.1 Analog Outputs With A PLC

- •22.3.2 Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) Outputs

- •22.3.3 Shielding

- •22.4 DESIGN CASES

- •22.4.1 Process Monitor

- •22.5 SUMMARY

- •22.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •22.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •22.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •23. CONTINUOUS SENSORS

- •23.1 INTRODUCTION

- •23.2 INDUSTRIAL SENSORS

- •23.2.1 Angular Displacement

- •23.2.1.1 - Potentiometers

- •23.2.2 Encoders

- •23.2.2.1 - Tachometers

- •23.2.3 Linear Position

- •23.2.3.1 - Potentiometers

- •23.2.3.2 - Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDT)

- •23.2.3.3 - Moire Fringes

- •23.2.3.4 - Accelerometers

- •23.2.4 Forces and Moments

- •23.2.4.1 - Strain Gages

- •23.2.4.2 - Piezoelectric

- •23.2.5 Liquids and Gases

- •23.2.5.1 - Pressure

- •23.2.5.2 - Venturi Valves

- •23.2.5.3 - Coriolis Flow Meter

- •23.2.5.4 - Magnetic Flow Meter

- •23.2.5.5 - Ultrasonic Flow Meter

- •23.2.5.6 - Vortex Flow Meter

- •23.2.5.7 - Positive Displacement Meters

- •23.2.5.8 - Pitot Tubes

- •23.2.6 Temperature

- •23.2.6.1 - Resistive Temperature Detectors (RTDs)

- •23.2.6.2 - Thermocouples

- •23.2.6.3 - Thermistors

- •23.2.6.4 - Other Sensors

- •23.2.7 Light

- •23.2.7.1 - Light Dependant Resistors (LDR)

- •23.2.8 Chemical

- •23.2.8.2 - Conductivity

- •23.2.9 Others

- •23.3 INPUT ISSUES

- •23.4 SENSOR GLOSSARY

- •23.5 SUMMARY

- •23.6 REFERENCES

- •23.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •23.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •23.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •24. CONTINUOUS ACTUATORS

- •24.1 INTRODUCTION

- •24.2 ELECTRIC MOTORS

- •24.2.1 Basic Brushed DC Motors

- •24.2.2 AC Motors

- •24.2.3 Brushless DC Motors

- •24.2.4 Stepper Motors

- •24.2.5 Wound Field Motors

- •24.3 HYDRAULICS

- •24.4 OTHER SYSTEMS

- •24.5 SUMMARY

- •24.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •24.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •24.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •25. CONTINUOUS CONTROL

- •25.1 INTRODUCTION

- •25.2 CONTROL OF LOGICAL ACTUATOR SYSTEMS

- •25.3 CONTROL OF CONTINUOUS ACTUATOR SYSTEMS

- •25.3.1 Block Diagrams

- •25.3.2 Feedback Control Systems

- •25.3.3 Proportional Controllers

- •25.3.4 PID Control Systems

- •25.4 DESIGN CASES

- •25.4.1 Oven Temperature Control

- •25.4.2 Water Tank Level Control

- •25.5 SUMMARY

- •25.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •25.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •25.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •26. FUZZY LOGIC

- •26.1 INTRODUCTION

- •26.2 COMMERCIAL CONTROLLERS

- •26.3 REFERENCES

- •26.4 SUMMARY

- •26.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •26.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •26.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •27. SERIAL COMMUNICATION

- •27.1 INTRODUCTION

- •27.2 SERIAL COMMUNICATIONS

- •27.2.1.1 - ASCII Functions

- •27.3 PARALLEL COMMUNICATIONS

- •27.4 DESIGN CASES

- •27.4.1 PLC Interface To a Robot

- •27.5 SUMMARY

- •27.6 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •27.7 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •27.8 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •28. NETWORKING

- •28.1 INTRODUCTION

- •28.1.1 Topology

- •28.1.2 OSI Network Model

- •28.1.3 Networking Hardware

- •28.1.4 Control Network Issues

- •28.2 NETWORK STANDARDS

- •28.2.1 Devicenet

- •28.2.2 CANbus

- •28.2.3 Controlnet

- •28.2.4 Ethernet

- •28.2.5 Profibus

- •28.2.6 Sercos

- •28.3 PROPRIETARY NETWORKS

- •28.3.1 Data Highway

- •28.4 NETWORK COMPARISONS

- •28.5 DESIGN CASES

- •28.5.1 Devicenet

- •28.6 SUMMARY

- •28.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •28.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •28.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •29. INTERNET

- •29.1 INTRODUCTION

- •29.1.1 Computer Addresses

- •29.1.2 Phone Lines

- •29.1.3 Mail Transfer Protocols

- •29.1.4 FTP - File Transfer Protocol

- •29.1.5 HTTP - Hypertext Transfer Protocol

- •29.1.6 Novell

- •29.1.7 Security

- •29.1.7.1 - Firewall

- •29.1.7.2 - IP Masquerading

- •29.1.8 HTML - Hyper Text Markup Language

- •29.1.9 URLs

- •29.1.10 Encryption

- •29.1.11 Compression

- •29.1.12 Clients and Servers

- •29.1.13 Java

- •29.1.14 Javascript

- •29.1.16 ActiveX

- •29.1.17 Graphics

- •29.2 DESIGN CASES

- •29.2.1 Remote Monitoring System

- •29.3 SUMMARY

- •29.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •29.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •29.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •30. HUMAN MACHINE INTERFACES (HMI)

- •30.1 INTRODUCTION

- •30.2 HMI/MMI DESIGN

- •30.3 DESIGN CASES

- •30.4 SUMMARY

- •30.5 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •30.6 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •30.7 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •31. ELECTRICAL DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION

- •31.1 INTRODUCTION

- •31.2 ELECTRICAL WIRING DIAGRAMS

- •31.2.1 Selecting Voltages

- •31.2.2 Grounding

- •31.2.3 Wiring

- •31.2.4 Suppressors

- •31.2.5 PLC Enclosures

- •31.2.6 Wire and Cable Grouping

- •31.3 FAIL-SAFE DESIGN

- •31.4 SAFETY RULES SUMMARY

- •31.5 REFERENCES

- •31.6 SUMMARY

- •31.7 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •31.8 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •31.9 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •32. SOFTWARE ENGINEERING

- •32.1 INTRODUCTION

- •32.1.1 Fail Safe Design

- •32.2 DEBUGGING

- •32.2.1 Troubleshooting

- •32.2.2 Forcing

- •32.3 PROCESS MODELLING

- •32.4 PROGRAMMING FOR LARGE SYSTEMS

- •32.4.1 Developing a Program Structure

- •32.4.2 Program Verification and Simulation

- •32.5 DOCUMENTATION

- •32.6 COMMISIONING

- •32.7 REFERENCES

- •32.8 SUMMARY

- •32.9 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •32.10 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •32.11 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •33. SELECTING A PLC

- •33.1 INTRODUCTION

- •33.2 SPECIAL I/O MODULES

- •33.3 SUMMARY

- •33.4 PRACTICE PROBLEMS

- •33.5 PRACTICE PROBLEM SOLUTIONS

- •33.6 ASSIGNMENT PROBLEMS

- •34. FUNCTION REFERENCE

- •34.1 FUNCTION DESCRIPTIONS

- •34.1.1 General Functions

- •34.1.2 Program Control

- •34.1.3 Timers and Counters

- •34.1.4 Compare

- •34.1.5 Calculation and Conversion

- •34.1.6 Logical

- •34.1.7 Move

- •34.1.8 File

- •34.1.10 Program Control

- •34.1.11 Advanced Input/Output

- •34.1.12 String

- •34.2 DATA TYPES

- •35. COMBINED GLOSSARY OF TERMS

- •36. PLC REFERENCES

- •36.1 SUPPLIERS

- •36.2 PROFESSIONAL INTEREST GROUPS

- •36.3 PLC/DISCRETE CONTROL REFERENCES

- •37. GNU Free Documentation License

- •37.1 PREAMBLE

- •37.2 APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS

- •37.3 VERBATIM COPYING

- •37.4 COPYING IN QUANTITY

- •37.5 MODIFICATIONS

- •37.6 COMBINING DOCUMENTS

- •37.7 COLLECTIONS OF DOCUMENTS

- •37.8 AGGREGATION WITH INDEPENDENT WORKS

- •37.9 TRANSLATION

- •37.10 TERMINATION

- •37.11 FUTURE REVISIONS OF THIS LICENSE

- •37.12 How to use this License for your documents

plc analog - 22.2

Outputs:

•fluid valve position

•motor position

•motor velocity

This chapter will focus on the general principles behind digital-to-analog (D/A) and analog-to-digital (A/D) conversion. The chapter will show how to output and input analog values with a PLC.

22.2 ANALOG INPUTS

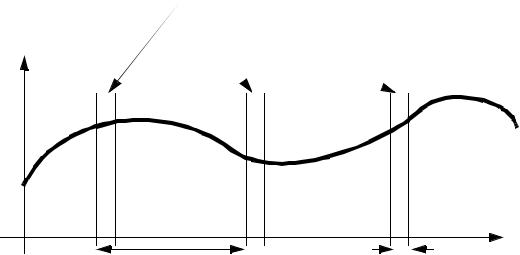

To input an analog voltage (into a PLC or any other computer) the continuous voltage value must be sampled and then converted to a numerical value by an A/D converter. Figure 22.2 shows a continuous voltage changing over time. There are three samples shown on the figure. The process of sampling the data is not instantaneous, so each sample has a start and stop time. The time required to acquire the sample is called the sampling time. A/D converters can only acquire a limited number of samples per second. The time between samples is called the sampling period T, and the inverse of the sampling period is the sampling frequency (also called sampling rate). The sampling time is often much smaller than the sampling period. The sampling frequency is specified when buying hardware, but for a PLC a maximum sampling rate might be 20Hz.

Voltage is sampled during these time periods

voltage |

|

|

time |

T = (Sampling Frequency)-1 |

Sampling time |

Figure 22.2 Sampling an Analog Voltage

plc analog - 22.3

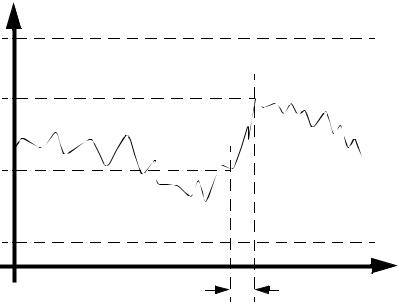

A more realistic drawing of sampled data is shown in Figure 22.3. This data is noisier, and even between the start and end of the data sample there is a significant change in the voltage value. The data value sampled will be somewhere between the voltage at the start and end of the sample. The maximum (Vmax) and minimum (Vmin) voltages are a function of the control hardware. These are often specified when purchasing hardware, but reasonable ranges are;

0V to 5V

0V to 10V -5V to 5V -10V to 10V

The number of bits of the A/D converter is the number of bits in the result word. If the A/D converter is 8 bit then the result can read up to 256 different voltage levels. Most A/D converters have 12 bits, 16 bit converters are used for precision measurements.

plc analog - 22.4

V( t) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vmax |

V( t2) |

|

|

|

|

V( t1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vm in |

|

|

|

|

t |

|

|

|

|

τ |

where, |

|

|

|

t1 t2 |

V( t) |

= the actual voltage over time |

|||

τ |

= |

sample interval for A/D converter |

||

t |

= time |

|

|

|

t1, t2 |

= time at start,end of sample |

|||

V( t1) , V( t2) |

= |

voltage at start, end of sample |

||

Vmin, Vmax |

= |

input voltage range of A/D converter |

||

N = |

number of bits in the A/D converter |

|||

Figure 22.3 Parameters for an A/D Conversion

The parameters defined in Figure 22.3 can be used to calculate values for A/D converters. These equations are summarized in Figure 22.4. Equation 1 relates the number of bits of an A/D converter to the resolution. In a normal A/D converter the minimum range value, Rmin, is zero, however some devices will provide 2’s compliment negative numbers for negative voltages. Equation 2 gives the error that can be expected with an A/D converter given the range between the minimum and maximum voltages, and the resolution (this is commonly called the quantization error). Equation 3 relates the voltage range and resolution to the voltage input to estimate the integer that the A/D converter will record. Finally, equation 4 allows a conversion between the integer value from the A/D converter, and a voltage in the computer.

plc analog - 22.5

R = 2 |

N |

= Rmax |

– Rmin |

|

(1) |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Vmax – Vmin |

(2) |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

2R |

|

|

|

VERRO R = ----------- |

----------------- |

|

|

|

|||||

VI |

= INT |

|

Vin – Vmin ( R – 1) + Rm in |

|

(3) |

||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Vm ax – Vmin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

VC |

= |

VI – Rm in |

– Vmin) + Vmin |

(4) |

|||||

----(-R-- – 1)-------------- |

( Vm ax |

|

|

||||||

where,

R, Rmin, Rmax = absolute and relative resolution of A/D converter

VI = the integer value representing the input voltage

VC = the voltage calculated from the integer value

VERROR = the maximum quantization error

Figure 22.4 A/D Converter Equations

Consider a simple example, a 10 bit A/D converter can read voltages between - 10V and 10V. This gives a resolution of 1024, where 0 is -10V and 1023 is +10V. Because there are only 1024 steps there is a maximum error of ±9.8mV. If a voltage of 4.564V is input into the PLC, the A/D converter converts the voltage to an integer value of 745. When we convert this back to a voltage the result is 4.565V. The resulting quantization error is 4.565V-4.564V=+0.001V. This error can be reduced by selecting an A/D converter with more bits. Each bit halves the quantization error.

plc analog - 22.6

Given,

N = 10, Rm in = 0

Vmax = 10V

Vmin = –10V

Vin = 4.564V

Calculate,

R = Rm ax = 2N = 1024

|

|

|

|

Vm ax – Vmin |

|

= 0.0098V |

|||||||

VERROR = -- |

---- |

-----2----R------- |

------ |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Vin – Vm in ( R – 1) |

|

|

|

||||||

VI |

= INT |

-- |

+ 0 |

= 745 |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

Vmax – Vmin |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

V |

V |

I |

– 0 |

( V |

|

– V |

|

) + V |

|

= 4.565V |

|||

= ---- |

-- |

---- |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

C |

R – 1 |

|

|

max |

|

min |

m in |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Figure 22.5 Sample Calculation of A/D Values

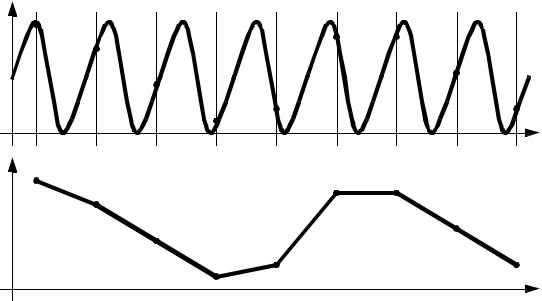

If the voltage being sampled is changing too fast we may get false readings, as shown in Figure 22.6. In the upper graph the waveform completes seven cycles, and 9 samples are taken. The bottom graph plots out the values read. The sampling frequency was too low, so the signal read appears to be different that it actually is, this is called aliasing.

plc analog - 22.7

Figure 22.6 Low Sampling Frequencies Cause Aliasing

The Nyquist criterion specifies that sampling frequencies should be at least twice the frequency of the signal being measured, otherwise aliasing will occur. The example in Figure 22.6 violated this principle, so the signal was aliased. If this happens in real applications the process will appear to operate erratically. In practice the sample frequency should be 4 or more times faster than the system frequency.

fAD > 2fsignal |

where, |

|

fAD = sampling frequency |

|

fsignal = maximum frequency of the input |

There are other practical details that should be considered when designing applications with analog inputs;

•Noise - Since the sampling window for a signal is short, noise will have added effect on the signal read. For example, a momentary voltage spike might result in a higher than normal reading. Shielded data cables are commonly used to reduce the noise levels.

•Delay - When the sample is requested, a short period of time passes before the final sample value is obtained.

•Multiplexing - Most analog input cards allow multiple inputs. These may share the A/D converter using a technique called multiplexing. If there are 4 channels

plc analog - 22.8

using an A/D converter with a maximum sampling rate of 100Hz, the maximum sampling rate per channel is 25Hz.

•Signal Conditioners - Signal conditioners are used to amplify, or filter signals coming from transducers, before they are read by the A/D converter.

•Resistance - A/D converters normally have high input impedance (resistance), so they affect circuits they are measuring.

•Single Ended Inputs - Voltage inputs to a PLC can use a single common for multiple inputs, these types of inputs are called single ended inputs. These tend to be more prone to noise.

•Double Ended Inputs - Each double ended input has its own common. This reduces problems with electrical noise, but also tends to reduce the number of inputs by half.