Snowdon & Vane Modern Macroeconomics

.pdf472 |

Modern macroeconomics |

Kreps’s ‘waiting’ – unless one is willing to admit that even in the long run ‘information about which state will prevail’ may not exist, and these economic decisions are made under a state of Keynesian uncertainty.

Probabilistic analysis of waiting and option value recognize only a need to postpone spending over time. However, only Keynesian uncertainty provides a basis for a long-run demand for liquidity and the possibility of long-run underemployment equilibrium.

8.11Conclusions

The fundamental building blocks of Post Keynesian theory are: (i) the nonneutrality of money; (ii) the existence of non-ergodic uncertainty in some important decision-making aspects of economic life; and (iii) the denial of the ubiquitousness of the gross substitution axiom. One way that humans have coped with having to make decisions where pay-offs will occur in the unforeseen and possibly unforeseeable future is via the development of the law of contracts by civilized societies, and the use of money as a chartalist means of discharging contracts. The abolition of slavery makes the enforcement of real contracts for human labour illegal. Accordingly, civilized society has decided not to permit ‘real contracting’ no matter how efficient it can be proved to be in neoclassical economics.

Keynes’s revolutionary analysis, where money is never neutral and liquidity matters, is a general theory of an economy where the complete unpredictability of the future may have important economic consequences. By contrast, neoclassical optimization requires restrictive fundamental postulates regarding uncertainty and hence expectations regarding future consequences that Keynes’s analysis does not. The analyst must therefore choose which system is more relevant for analysing the economic problem under study.

For many routine decisions, assuming the uniformity and consistency of nature over time (that is, assuming ergodicity) may be, by the definition of routine, a useful simplification for handling the problem at hand. For problems involving investment and liquidity decisions where large unforeseeable changes over long periods of calendar time cannot be ruled out, the Keynesian uncertainty model is more applicable. To presume a universe of discoverable regularities which can be expected to continue into the future and where the neutrality of money is therefore central (Lucas, 1981b, p. 561) will provide a misleading analogy for developing macro policies for monetary, production economies whenever money really matters and affects production decisions in the real economy.

Economists should be careful not to claim more for their discipline than they can deliver. The belief that in ‘some circumstances’ the world is probabilistic (Lucas and Sargent, 1981, pp. xi–xii), or that future prospects

The Post Keynesian school |

473 |

can be completely ordered, will tend to lead to the argument that individuals in free markets will not make persistent errors and will tend to know better than the government how to judge the future. Basing general rules on these particular assumptions can result in disastrous policy advice for governmental officials facing situations where many economic decision makers feel unable to draw conclusions about the future from the past.

However, if economists can recognize and identify when these (non-ergodic) economic conditions of true uncertainty are likely to be prevalent, government can play a role in improving the economic performance of markets. Economists should strive to design institutional devices which can produce legal constraints on the infinite universe of events which could otherwise occur as the economic process moves through historical time. For example, governments can set up financial safety nets to prevent, or at least offset, disastrous consequences that might occur, and also provide monetary incentives to encourage individuals to take civilized actions which are determined by democratic processes to be in the social interest (Davidson and Davidson, 1988). Where private institutions do not exist, or need buttressing against winds of true uncertainty, government should develop economic institutions which attempt to reduce uncertainties by limiting the possible consequences of private actions to those that are compatible with full employment and reasonable price stability.

9. The Austrian school

Roger W. Garrison*

Mr. Keynes’s aggregates conceal the most fundamental mechanisms of change. (Hayek, 1931)

9.1The Mengerian Vision

The Austrian school is best known for its microeconomics and, in particular, for its role in the marginalist revolution. In the early 1870s, Carl Menger, along with French economist Léon Walras and English economist William Stanley Jevons, reoriented value theory by calling attention to the marginal unit of a good as key to our understanding the determination of the good’s market price. With marginality central to the analysis, microeconomics was forever changed. It is less widely recognized, however, that a viable macroeconomic construction also arises quite naturally out of the marginalist revolution in the context of Menger’s vision of a capital-using market economy.

Modern macroeconomics makes a distinction between factor markets (inputs) and product markets (outputs). Intermediate inputs and outputs are rarely in play. By contrast, the economics of the Austrian school features a production process – a sequence of activities in which the outputs associated with some activities feed in as inputs to subsequent activities. The eventual yield of consumable output constitutes the end of the sequence. Menger (1981 [1871]) set out the theory in terms of ‘orders of goods’, the first, or lowest, order constituting consumer goods and second, third and higher orders constituting producers’ goods increasingly remote in time from goods of the lowest order. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1959 [1889]) introduced the similar notion of ‘maturity classes’ to capture this temporal element in the economy’s production process. He stressed the point that an increase in the economy’s growth rate must entail an increase in activity in the earlier maturity classes relative to (concurrent) activity in the later maturity classes.

*Roger W. Garrison, Professor of Economics at Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama (USA), is the author of Time and Money: The Macroeconomics of Capital Structure (London: Routledge, 2001). He gratefully acknowledges helpful suggestions offered by Lane Boyte and Sven Thommesen during the preparation of this chapter.

474

The Austrian school |

475 |

Böhm-Bawerk was possibly the first economist to insist that propositions about the macroeconomy have firm microeconomic foundations. In an 1895 essay, he wrote that ‘One cannot eschew studying the microcosm if one wants to understand properly the macrocosm of a developed economy’ (Hennings, 1997, p. 74). Ludwig von Mises (1953 [1912]), who is generally credited for using marginal utility analysis to account for the value of money, was also the first to recognize the significance of credit creation in the context of a decentralized, time-consuming production process. The capital theory originated by Menger and the theory of money and credit set out by Mises were developed by Friedrich Hayek (1967 [1935]) into the Austrian theory of the business cycle. Lionel Robbins (1971 [1934]) and Murray Rothbard (1963) applied the theory to the interwar episode of boom and bust. Eventually, the insights of these and other Austrians gave rise to a full-fledged capital-based macroeconomics (Horwitz, 2000 and Garrison, 2001; see also Littlechild, 1990).

9.2The Intertemporal Structure of Capital

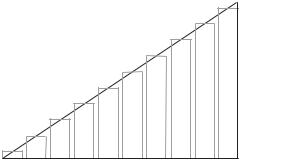

Hayek greatly simplified the Austrian vision of a capital-using economy by modelling the economy’s production activities as a sequence of inputs and a point output. Each element in the sequence is designated a ‘stage of production’, the number of stages posited being largely a matter of pedagogical convenience. This simple construction was first introduced as a bar chart with the individual bars arrayed temporally, their (equal) widths representing increments of production time. The length of the final bar represents the value of consumable output; the attenuated lengths of the preceding bars represent the values of the goods in process at the various stages of production.

Figure 9.1 shows ten stages of production arrayed from left to right. (In the original Hayekian rendition, five stages were arrayed from top to bottom.) The specific number of stages is not intended to quantify any actual, empirically established detail about the economy’s production process but rather to capture our general understanding that in many instances the (intermediate) output of one stage is used as an input to a subsequent stage. That is, vertical integration – and, certainly, complete vertical integration – is not the norm. Hayek’s ‘stages’ do not translate cleanly into ‘firms’ or ‘industries’. Some vertically integrated activities may be carried out within a single firm. An oil company, for example, may be engaged in exploring, extracting, refining, distributing and retailing. A paper manufacturer, for another example, may be supplying paper for blueprints and for greeting cards, thus operating simultaneously in different stages. And there are obvious deviations from the strict one-way temporal sequence: coal may be used in the production of steel while steel is used in the production of coal.

476 |

Modern macroeconomics |

Late stages

Consumable

Early output

stages

Stages of production

Figure 9.1 The intertemporal structure of production

(This is the supposedly telling counter-example offered by Frank Knight in his critical introduction to the English translation of Menger’s Principles.) Still, as with all simple models, this Austrian model of the capital structure is notable not for its many sins of omission but rather for the essential truths that are captured by its construction.

Means are employed to achieve ends, and those means are temporally prior to the corresponding ends. Production moves forward through time. Valuation, however, emanates in the reverse direction. That is, the anticipated value of an end attaches itself to the means capable of achieving that end. This is Menger’s Law. The demand for the factors of production and hence for the outputs of the intermediate stages of production is a derived demand. The direction of valuation is implicit in Menger’s designation of consumption goods as ‘goods of the first order’. The market values of goods of the second, third and higher orders are ultimately derived from the anticipated value of the first-order goods. But even with the doctrine of derived demand fully in play, those values entail a systematic time discount consistent with the temporal remoteness of higher-order goods.

The Austrian vision puts the entrepreneur in a key role. At a minimum, the entrepreneur operating in some particular stage of production must anticipate the demand for his own output, assessing the profitability of his activities with due attention to the cost of borrowed funds. Longer-run planning may require gauging the strength of demand several stages forward, including ultimately the demand for the consumable output. Speculative activities may consist in part in the movement of resources – in response to a change in credit conditions

– from one stage to another and possibly in the creation of new stages of production that are of a higher order than the highest order of the existing stages. The increasing ‘roundaboutness’, to use Böhm-Bawerk’s term, and the

The Austrian school |

477 |

increasing significance of the time element in the production process, are characteristic of developing (and developed) capitalist economies.

The attention to the temporal structure of production suggests that the time element is an important variable in our understanding of how a decentralized economy works to coordinate production activities with consumer preferences and hence in our understanding of what might go wrong with the coordinating mechanisms. The use of multiple stages of production gives full play to marginalist thinking. Austrian macro is micro-friendly. The pattern of resource allocation can be modified in systematic ways, changing the temporal profile of production activities. A marginal decrease in late-stage activities coupled with a marginal increase in early-stage activities has important implications for the economy’s overall growth rate. Significantly, a related pattern of marginal changes gives rise to boom and bust. Changes in the intertemporal pattern of resource allocation have a claim on our attention, according to the Austrians, even if these marginal changes cancel one another out in some conventional macroeconomic aggregate such as investment spending (in all stages) or total spending (by both consumers and the investment community).

The pattern of resource allocation associated with intertemporal equilibrium exhibits a certain uniformity in terms of the value differentials that separate the stages of production. The difference in the value of the output of one stage and the value of the output of the next stage reflects, among other things, the general terms of intertemporal exchange, expressed summarily as the market rate of interest. With a given rate of interest, excessive stage-to- stage value differentials would present themselves as profit opportunities which could be exploited only by reallocating resources toward the earlier stages of production. In the limit, when all such profit opportunities have been competed away, the relative prices of inputs used in the various stages are brought into line with the equilibrium rate of interest. A summary graphical rendering of the intertemporal capital structure takes the form of a triangle encasing the sequence of stages that constitute such an intertemporal equilibrium. The Hayekian triangle in Figure 9.1 keeps the many complexities of capital theory at bay while keeping in play the overall time element in the production process.

The extreme level of simplification warrants some discussion. First, we note that the triangle’s hypotenuse, which tracks the value of the yet-to-be completed consumables, rises linearly from no value at all to the full market value of the consumables. Yet we know that the interest rate is expressed in percentage terms and, starting from some initial input value, allows for compounding. Clearly – and contrary to the Hayekian triangle – such percentage value differentials imply that the cumulative value should be tracked by a curve that rises exponentially from some initial value to some final value.

478 |

Modern macroeconomics |

Here, linearity wins out on the grounds of its being simpler in construction yet adequate to the task. It is also true to Hayek’s original formulation. We need to recognize, however, that the triangle would be inadequate for dealing with any issue for which the compounding effect is critical. Ambiguities about the precise relationship between the interest rate and the overall degree of roundaboutness arise when the effects of compound interest are factored in. These and related ambiguities concerning capital intensity lay at the heart of the Cambridge capital controversy (see Harcourt, 1972), a protracted and, ultimately, sterile debate that attracted much attention a few decades ago. But for dealing with the business cycle and related macroeconomic issues, the triangle, simple as it is, does just fine.

Second, the horizontal leg of the triangle, which invites us to imagine a sequence of unit time intervals, does not translate readily into calendar time. In application, an early stage of production consists only partly in goods in process – pine saplings that mature over time into lumber or wine that undergoes an ageing process. Earliness is also implicit in durable capital goods or even in human capital. These factors of production are categorized as early-stage because they will have a yield over an extended future. The heterogeneity of capital warns against trying to create a single metric, such as some average period of production, or to quantify in some other way the production time for the macroeconomy. Still, many early-stage activities and late-stage activities are readily discernible. Inventory management at retail is a late-stage activity. Product development is an early-stage activity. Increases in the time dimension of the economy’s capital structure might take the form of shifting resources from relatively late to relatively early stages, of creating capital goods of greater durability, or of simply changing the mix of goods produced in favour of those involving more time-consuming (but higheryielding) production processes.

Third, the vertical leg of the Hayekian triangle, which represents the value of consumable output, implies that consumption occurs at a single point in time at the end of the production process. This is not to deny the existence of consumer durables. But expanding the intertemporal aspect of the macroeconomy to include consumption time would complicate matters without adding much to the analysis. The triangle focuses attention on the particulars of production and on aspects of the market process that lose much of their relevance once the goods are in the hands of the consumer. The notion of ‘stages of consumption’ would be contrived if not meaningless.

In application there is a fine line – in Austrian theory as in more conventional theory – between an investment good and a consumer durable. Residential housing, whether or not owner-occupied, is universally categorized as investment, the rental value (actual or implicit) of its services qualifying as consumption. Owner-driven automobiles, however, despite their

The Austrian school |

479 |

considerable durability and implicit lease value, are categorized as consumption goods. Instances can be imagined in which a consumable (for example a light truck purchased new for non-commercial use) is later sold into an early stage of production (for example as a work truck). But as a general rule, goods delivered into the hands of consumers stay in the hands of consumers. Attention to these and related matters may be necessary in particular applications of the Austrian theory, but the theory itself is based on the vision of a multi-stage production process that yields a consumable output.

In its simplest interpretation, Figure 9.1 represents a no-growth economy. Gross investment, financed by saving, is just enough to offset capital depreciation. With given tastes and technology, the macroeconomy settles into an intertemporal equilibrium and produces consumption goods at an unchanging rate. More typically, saving and gross investment exceed capital depreciation, allowing the economy to grow at every margin. If we can assume for the moment an unchanging rate of interest, the growth can be represented by a triangle of increasing size, its general shape remaining the same.

The pay-off to Hayekian triangulation, however, comes from allowing for changes in the triangle’s shape. More conventional macroeconomic constructions make the implicit assumption of structural fixity or structural irrelevance. In the Austrian theory, changes in saving behaviour have implications for the allocation of resources within the economy’s capital structure. In turn, the changing shape of the triangle affects the time profile of consumable output. The natural focus of the analysis is on intertemporal coordination and possible causes of intertemporal discoordiantion.

9.3Saving and Economic Growth

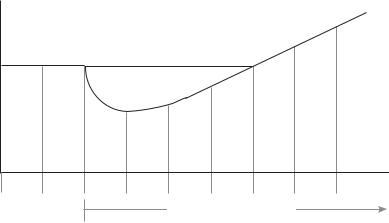

We tend to think of economies as experiencing some ongoing rate of growth. The growth rate will be positive, negative, or zero, depending upon the relationship between saving and capital depreciation. In a stationary, or nogrowth, economy, saving finances just enough investment to offset capital depreciation. Consumable output is constant over time, as depicted in the first two periods in Figure 9.2.

If saving is in excess of capital depreciation, the economy grows. The volume of consumable output rises over time, as depicted in the last three periods of Figure 9.2. The output of each of the stages of production increases as well. The economy grows at every margin, allowing even for a continual increase in the number of stages. During a period of secular growth, the Hayekian triangle increases in size but not – or not necessarily – in shape.

An interesting question, one whose answer serves as a prelude to the Austrian analysis of business cycles, concerns the transition from no growth to a positive rate of growth – or, for that matter, from some initial growth rate to a

480 |

Modern macroeconomics |

Consumable output

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Time |

saving > depreciation

Figure 9.2 A possible temporal pattern of consumable output

higher growth rate. What must be true about the time profile of consumable output during the transition? Let’s assume that there has been no change in the state of technology or in the general availability of resources. We assume, though, that people’s intertemporal preferences change if favour of future consumption. If confronted with the simple choice between no growth and growth, people would surely prefer the latter. The choice, however, is never quite that simple. The memorable acronym introduced by science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein (1966) applies. TANSTAAFL: ‘There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch’. Modifying the acronym to fit the application, we recognize that TANSTAFG. Free growth is not available for the asking, either.

The relevant trade-off is that between consumable output in the near future and consumable output in the more remote future. Are people willing to forgo some current and near-term consumption in order to enjoy increasing consumption over an extended period? It is the forgoing of current and near-term consumption, after all, that frees up the resources with which to expand the economy’s productive capacity and make increasing future consumption possible. In Figure 9.2 the hypothesized preference change occurs at the end of the second period. In light of this change, the output of consumption goods during the third period needs to be reduced. The freed-up resources can be employed in earlier stages of production. So altered, the capital structure will eventually begin yielding consumables at an increased rate, matching the initial output level at the end of the sixth period (in this particular example) and exceeding it in the subsequent periods.

The market economy, in the judgement of the Austrians, is capable of tailoring intertemporal production activities to match intertemporal consump-

The Austrian school |

481 |

||||

8 |

|

|

|

||

7 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

6 |

|

|

|

||

5 |

Initial |

||||

4 |

consumable |

||||

3 |

output |

||||

1&2 |

|

|

|

||

Stages of production |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initial highest |

|

|

|

||

stage of production |

|

|

|

||

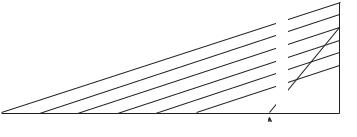

Figure 9.3 Intertemporal capital restructuring

tion preferences. The temporal pattern of consumable output shown in Figure 9.2 requires a capital restructuring, as can be depicted by a change in the Hayekian triangle’s shape. Figure 9.3 shows the general nature of the required change. The no-growth periods 1 and 2, which pre-date the preference change, are depicted by the triangle having a relatively short intertemporal capital structure. Beginning with the preference change at the end of period 2, consumption falls, reaching a minimum at the end of period 3. The freedup resources can be allocated to the early stages of production and to the creation of still earlier stages, enhancing the ability of the economy to produce consumable output in the future. The reduced near-term yield of consumable output and the increased number of stages of production are depicted by the triangle 3, the smallest of the reshaped triangles.

As goods in process begin to move through the restructured sequence of stages, the output of consumables begins to rise, and with saving now in excess of capital depreciation, expansion continues in each of the stages of production. The economy experiences a positive secular growth rate, as shown by the triangles 4 through 8, triangle 6 having the same consumable output as the initial no-growth triangle. Yet to be discussed are the market mechanisms that actually bring about this capital restructuring. At this point, the focus is on the correspondence between the intertemporal capital restructuring shown in Figure 9.3 and the temporal pattern of consumable output shown in Figure 9.2.

The attention here to a one-time simple preference change resulting in a transition from a no-growth economy to an economy experiencing a positive secular growth rate finds justification in analytical and heuristic convenience. More complex preference changes can easily be imagined. Actual changes in intertemporal preferences may themselves be gradual, and the preferred time profile of consumables is undoubtedly not as simply described as is the intertemporal pattern in Figure 9.2. This is only to say that a decentralized