Snowdon & Vane Modern Macroeconomics

.pdf422 |

Modern macroeconomics |

understood the dynamics of inflation very well. Indeed it was not until the mid- to-late 1970s that intermediate textbooks began emphasising the absence of a long-run trade-off between inflation and output. The ideas that expectations matter in generating inflation and that credibility is important in policymaking were simply not well established during that era’ (see also Taylor, 1997a; Mayer, 1999; Romer and Romer, 2004). To understand the historical performance of an economy over time it would seem imperative to have an understanding of the policy maker’s knowledge during the time period under investigation. Since a great deal of policy makers’ knowledge is derived from the research findings of economists, the state of economists’ knowledge at each point in history must always be taken into consideration when assessing economic performance (Romer and Romer, 2002). Although it is a very important task of economists to analyse and be critical of past policy errors, we should remember that, as with all things, it is easy to be wise after the event.

While a consensus among new Keynesian economists would support the new Keynesian style of monetary policy outlined above, there remain doubters. For example, Stiglitz (1993, pp. 1069–70) prefers a more flexible approach to policy making and argues:

Changing economic circumstances require changes in economic policy, and it is impossible to prescribe ahead of time what policies would be appropriate … The reality is that no government can stand idly by as 10, 15, or 20 percent of its workers face unemployment … new Keynesian economists also believe that it is virtually impossible to design rules that are appropriate in the face of a rapidly changing economy.

7.11.4 Other policy implications

For those new Keynesians who have been developing various explanations of real wage rigidity, a number of policy conclusions emerge which are aimed specifically at reducing highly persistent unemployment (Manning, 1995; Nickell, 1997, 1998). The work of Lindbeck and Snower (1988b) suggests that institutional reforms are necessary in order to reduce the power of the insiders and make outsiders more attractive to employers. Theoretically conceivable power-reducing policies include:

1.a softening of job security legislation in order to reduce the hiring and firing (turnover) costs of labour; and

2.reform of industrial relations in order to lessen the likelihood of strikes.

Policies that would help to ‘enfranchise’ the outsiders would include:

1.retraining outsiders in order to improve their human capital and marginal product;

The new Keynesian school |

423 |

2.policies which improve labour mobility; for example, a better-function- ing housing market;

3.profit-sharing arrangements which bring greater flexibility to wages;

4.redesigning of the unemployment compensation system so as to encourage job search.

Weitzman (1985) has forcefully argued the case for profit-sharing schemes on the basis that they offer a decentralized, automatic and market incentive approach to encourage wage flexibility, which would lessen the impact of macroeconomic shocks. Weitzman points to the experience of Japan, Korea and Taiwan with their flexible payment systems which have enabled these economies in the past to ride out the business cycle with relatively high output and employment levels (see Layard et al., 1991, for a critique).

The distorting impact of the unemployment compensation system on unemployment is recognized by many new Keynesian economists. A system which provides compensation for an indefinite duration without any obligation for unemployed workers to accept jobs offered seems most likely to disenfranchise the outsiders and raise efficiency wages in order to reduce shirking (Shapiro and Stiglitz, 1984). In the shirking model the equilibrium level of involuntary unemployment will be increased if the amount of unemployment benefit is raised. Layard et al. (1991) also favour reform of the unemployment compensation system (see Atkinson and Micklewright, 1991, for a survey of the literature).

Some new Keynesians (particularly the European branch) favour some form of incomes policy to modify the adverse impact of an uncoordinated wage bargaining system; for example, Layard et al. (1991) argue that ‘if unemployment is above the long-run NAIRU and there is hysteresis, a temporary incomes policy is an excellent way of helping unemployment return to the NAIRU more quickly’ (see also Galbraith, 1997). However, such policies remain extremely contentious and most new Keynesians (for example, Mankiw) do not feel that incomes policies have a useful role to play.

7.12Keynesian Economics Without the LM Curve

The modern approach to stabilization policy outlined in section 7.11 above is now reflected in the ideas taught to students of economics, even at the principles level (see D. Romer, 2000; Taylor, 2000b, 2001). The following simple model is consistent with the macroeconomic models that are currently used in practice by the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England (see Bank of England, 1999; Taylor, 1999; Clarida et al., 2000). Following Taylor (2000b), the model consists of three basic relationships. First, a negative relationship between the real rate of interest and GDP of the following form:

424 |

Modern macroeconomics |

|

|

y = −ar + µ |

(7.20) |

where y measures real GDP relative to potential GDP, r is the real rate of interest, µ is a shift term which, for example, captures the influence of exogenous changes to exports and government expenditures and so on. A higher real rate of interest depresses total demand in an economy by reducing consumption and investment expenditures, and also net exports via exchange rate appreciation in open economies with floating exchange rates. This relationship is ‘analogous’ to the IS curve of conventional textbook IS–LM analysis. The second key element in the model is a positive relationship between inflation and the real rate of interest of the form:

˙ |

(7.21) |

r = bP + v |

where ˙ is the rate of inflation and v is a shift term. This relationship, which

P

closely mirrors current practice at leading central banks, indicates that when inflation rises the monetary authorities will act to raise the short-term nominal interest rate sufficient to raise the real rate of interest. As Taylor (2000b) and D. Romer (2000) both point out, central banks no longer target monetary aggregates but follow a simple real interest rate rule. The third key relationship underlying the modern monetary policy model is a ‘Phillips curve’ type relationship between inflation and GDP of the form:

˙ ˙ |

+ cyt−1 + w |

(7.22) |

P = Pt−1 |

where w is a shift term. As equation (7.22) indicates, inflation will increase with a lag when actual GDP is greater than potential GDP (y > y*) and vice versa. The lag in the response of inflation to the deviation of actual GDP from potential GDP reflects the staggered price-setting behaviour of firms with market power inducing nominal stickiness. While this aspect indicates the new Keynesian flavour of this model, the relationship also allows for expectations of inflation to influence the actual rate.

From these three simple relationships we can construct a graphical illustration of the modern approach to stabilization policy. Combining equations (7.20) and (7.21) yields the following equation:

˙ |

(7.23) |

y = −abP + µ− av |

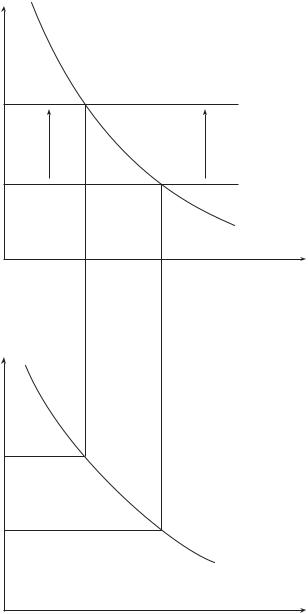

Equation (7.23) indicates a negatively sloped relationship between inflation and real GDP, which both Taylor and Romer call an aggregate demand (AD) curve. Figure 7.15 illustrates the derivation of the aggregate demand curve.

The new Keynesian school |

425 |

(a) |

Real |

interest |

rate |

MP1 |

r1 |

MP0 |

r0 |

IS |

Output |

(b) |

Inflation |

˙ |

P1 |

˙ |

P0 |

AD |

Output |

Figure 7.15 Derivation of the AD curve

426 Modern macroeconomics

For simplicity, if we assume that the central bank’s choice of real interest rate depends entirely on its inflation objective, the monetary policy (MP) real rate rule can be shown as a horizontal line in panel (a) of Figure 7.15, with shifts of the MP curve determined by the central bank’s reaction to changes in the rate of inflation. Equation (7.20) is represented by the IS curve in Figure 7.15. In panel (b) of Figure 7.15 we see equation (7.23) illustrated by a downward-sloping aggregate demand curve in inflation–output space. The intuition here is that as inflation rises the central bank raises the real rate of interest, thereby dampening total expenditure in the economy and causing GDP to decline. Similarly, as inflation falls, the central bank will lower the real rate of interest, thereby stimulating total expenditure in the economy and raising GDP. We can think of this response as the central bank’s monetary policy rule (Taylor, 2000b).

Shifts of the AD curve would result from exogenous shocks to the various components to aggregate expenditure, for example the AD curve will shift to the right in response to an increase in government expenditure, a decrease in taxes, an increase in net exports, or an increase in consumer and/or business confidence that leads to increased expenditures. The AD curve will also shift in response to a change in monetary policy. For example, if the monetary authorities decide that inflation is too high under the current monetary policy rule, they will shift the rule, raise real interest rates and shift the AD curve to the left (see Taylor, 2001).

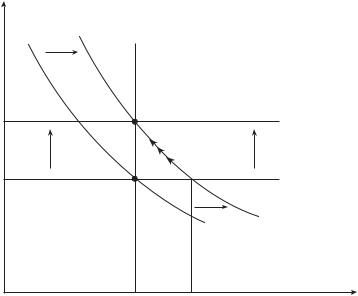

The Phillips curve or inflation adjustment relationship, given by equation (7.22), is represented by the horizontal line labelled IA0 in Figure 7.16. Following Taylor (2000b) and D. Romer (2000), this can be thought of as the aggregate supply component of the model, assuming first that the immediate impact of an increase in aggregate demand will fall entirely on aggregate output, and second that when actual GDP equals potential or ‘natural’ GDP (y = y*), inflation will be steady, but when y > y*, inflation will increase and when y < y*, inflation will decline. Both of these assumptions are consistent with the empirical evidence and supported by new Keynesian theories of wage and price stickiness in the short run (Gordon, 1990). When the economy is at its potential output the IA line will also shift upwards in response to supply-side shocks such as a rise in commodity prices and in response to shifts in inflationary expectations. Figure 7.16 illustrates the complete AD–IA model.

Long-run equilibrium in this model requires that AD intersect IA at the natural rate of output (y*). Assume that the economy is initially in long-run equilibrium at point ELR 0 and that an exogenous demand shock shifts the AD curve from AD0 to AD1. The initial impact of this shift is an increase in GDP

from y |

* |

˙ |

. Since y1 |

* |

|

to y1, with inflation remaining at P0 |

> y , over time the rate |

of inflation will increase, shifting the IA curve upwards. The central bank will respond to this increase in inflation by raising the real rate of interest, shown

The new Keynesian school |

427 |

Inflation |

|

|

|

|

˙ |

ELR1 |

|

IA |

|

P1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

˙ |

ELR0 |

|

IA |

|

P0 |

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AD1 |

|

|

|

|

AD0 |

|

|

y* |

y1 |

|

Output |

Figure 7.16 Adjusting to long-run equilibrium in the AD-IA model

by an upward shift of the MP curve in the IS–MP diagram (Figure 7.15). The IA curve continues to shift upwards until the AD and IA curves intersect at the potential level of output y*, that is, where AD1 and IA1 intersect. The economy is now at a new long-run equilibrium shown by ELR 1, but with a higher steady

˙

rate of inflation of P . The central bank has responded to the demand shock

1

by increasing the real rate of interest from r0 to r1. If the central bank decides that the new steady rate of inflation is too high (that is, above its inflation target), then it would have to take steps to shift the AD curve to the left by changing its monetary policy rule. This would lead to a recession (y < y*) and declining inflation. As the IA curve shifts down, the central bank will reduce real interest rates, stimulating demand, and the economy will return to y* at a lower steady rate of inflation.

The simple model described above gives a reasonably accurate portrayal of how monetary policy is now conducted. In Taylor’s (2000b) view this theory ‘fits the data well and explains policy decisions and impacts in a realistic way’. Whether this approach eventually becomes popularly known as ‘new Keynesian’ (Clarida et al., 2000; Gali, 2002) or as ‘new neoclassical synthesis’ (Goodfriend and King, 1997) remains to be seen. David Romer (2000) simply calls it ‘Keynesian macroeconomics without the LM curve’.

428 |

Modern macroeconomics |

7.13Criticisms of New Keynesian Economics

The new Keynesian research programme has been driven by the view that the orthodox Keynesian model lacked coherent microfoundations with respect to wage and price rigidities. As a result the new Keynesian literature has been, until recently, heavily biased towards theoretical developments. Many economists have been critical of the lack of empirical work, and Fair (1992) suggests that this literature has moved macroeconomics away from its econometric base and advises new Keynesians to ‘entertain the possibility of putting their various ideas together to produce a testable structural macroeconometric model’. Laidler (1992a) also argues forcefully for the reinstatement of empirical evidence as a research priority in macroeconomics.

Table 7.2 Evidence on reasons for price stickiness

Theory of price stickiness |

Percentage of firms |

|

|

accepting theory |

|

|

|

|

Coordination failure – each firm waiting for others to |

|

60.6 |

change price first |

|

|

Cost-based pricing with lags |

|

55.5 |

Preference for varying product attributes other than price |

|

54.8 |

Implicit contracts – fairness to customers necessitates |

|

50.4 |

stable prices |

|

|

Explicit nominal contracts |

|

35.7 |

Costly price adjustment – menu costs |

|

30.0 |

Procyclical elasticity – demand curves become more |

|

29.7 |

inelastic as they shift to the left |

|

|

Psychological significance of pricing points |

|

24.0 |

Preference for varying inventories rather than change price |

20.9 |

|

Constant marginal cost and constant mark-ups |

|

19.7 |

Bureaucratic delays |

|

13.6 |

Judging quality by price – fear that customers will interpret |

10.0 |

|

reductions in price as a reduction in quality |

|

|

Source: Adapted from Blinder (1994).

The new Keynesian school |

429 |

In response, new Keynesians can point to the non-orthodox but interesting and innovative research by Blinder (1991, 1994) into the pricing behaviour of firms, the empirical work related to testing the efficiency wage hypothesis (for example, Drago and Heywood, 1992; Capelli and Chauvin, 1991) and the influential paper by Ball et al. (1988) testing menu cost models using cross-country data. In seeking an answer to the important question ‘Why are prices sticky?’, Blinder’s research utilizes the data collected from interviews to discriminate between alternative explanations of price stickiness, which is regarded as a stylized fact by Keynesian economists (see Carlton, 1986, for evidence on price rigidities). Blinder’s results, reproduced in Table 7.2, give some support to Keynesian explanations which emphasize coordination failures, cost-plus pricing, preference for changing product attributes other than price, and implicit contracts.

In an interview (Snowdon, 2001a) Blinder summarized his findings on price stickiness in the following way:

of the twelve theories tested, many of the ones which come out best have a Keynesian flavour. When you list the twelve theories in the order that the respondents liked and agreed with them, the first is co-ordination failure – which is a very Keynesian idea. The second relates to the simple mark-up pricing model, which I might say is a very British-Keynesian idea. Some of the reasons given for price stickiness are not Keynesian at all. For example, non-price competition during a recession. The Okun (1981) implicit contract idea is also very Keynesian … if you look at the top five reasons given by firms as to why prices are sticky, four of them look distinctly Keynesian in character … To the extent that you are prepared to believe survey results, and some people won’t, I think this research strikes several blows in favour of Keynesian ideas.

Similar work by Bhaskar et al. (1993), utilizing data collected in the UK during the 1980s, confirms that most firms tend not to increase prices in booms or reduce them in recessions, but quantity adjustment responses via variations in hours, shift work, inventories or customer rationing are ‘overwhelmingly important’.

A second major problem with the new Keynesian literature is that it has yielded numerous elegant theories which are often unrelated (Gordon, 1990). This makes the pulling together of these ideas in order to produce a testable new Keynesian model all the more difficult. New Keynesians have themselves recognized this problem, with Blanchard (1992) reflecting that ‘we have constructed too many monsters’ with ‘few interesting results’. The fascination with constructing a ‘bewildering array’ of theories with their ‘quasi religious’ adherence to microfoundations has become a disease. Because there are too many reasons for wage and price inertia, no agreement exists on which source of rigidity is the most important (for a critique of efficiency wage theory, see Katz, 1986; Weiss, 1991).

430 |

Modern macroeconomics |

A third line of criticism also relates to the menu cost literature. Critics doubt that the small costs of price adjustment can possibly account for major contractions of output and employment (Barro, 1989a). Caplin and Spulber (1987) also cast doubt on the menu cost result by showing that, although menu costs may be important to an individual firm, this influence can disappear in the aggregate. In response to these criticisms, new Keynesians argue that the emerging literature which incorporates real rigidities widens the scope for nominal rigidities to have an impact on output and employment (see Ball and Romer, 1990; D. Romer, 2001). A further weakness of models incorporating small costs of changing prices is that they generate multiple equilibria. Rotemberg (1987) suggests that ‘if many things can happen the models are more difficult to reject’ and ‘when there are multiple equilibria it is impossible to know how the economy will react to any particular government policy’. Golosov and Lucas (2003) also highlight that in calibration exercises their menu cost model is consistent with the fact that ‘even large disinflations have small real effects if credibly carried out’.

A fourth criticism of new Keynesian economics relates to the emphasis it gives to deriving rigidities from microfoundations. Tobin (1993) denies that Keynesian macroeconomics ‘asserts or requires’ nominal and/or price rigidity. In Tobin’s view, wage and price flexibility would, in all likelihood, exacerbate a recession and he supports Keynes’s (1936) intuition that rigidity of nominal wages will act as a stabilizing influence in the face of aggregate demand shocks. Tobin also reminds the new Keynesians that Keynes had a ‘theoretically impeccable’ and ‘empirically realistic’ explanation of nominal wage rigidity based on workers’ concern with wage relativities. Since a nominal wage cut will be viewed by each group of workers as a relative real wage reduction (because workers have no guarantee in a decentralized system of knowing what wage cuts other groups of workers are accepting), it will be resisted by rational workers. Summers (1988) has taken up this neglected issue and suggests relative wage influences give rise to significant coordination problems. Greenwald and Stiglitz (1993b) have also developed a strand of new Keynesian theorizing which highlights the destabilizing impact of price flexibility.

A fifth criticism relates to the acceptance by many new Keynesians of the rational expectations hypothesis. Phelps (1992) regards the rational expectations hypothesis as ‘unsatisfactory’ and Blinder (1992a) notes that the empirical evidence in its favour is ‘at best weak and at worst damning’. Until someone comes up with a better idea, it seems unlikely that this line of criticism will lead to the abandonment of the rational expectations hypothesis in macroeconomics. However, with respect to the formation of expectations Leijonhufvud is enthusiastic about recent research into ‘Learning’ (see Evans and Honkapohja, 2001; Snowdon, 2004a).

The new Keynesian school |

431 |

A sixth problem identified with new Keynesian economics relates to the continued acceptance by the ‘new’ school of the ‘old’ IS–LM model as the best way of understanding the determinants of aggregate demand. King (1993) argues that the IS–LM model has ‘no greater prospect of being a viable analytical vehicle for macroeconomics in the 1990s than the Ford Pinto has of being a sporty, reliable car for the 1990s’. The basic problem identified by King is that, in order to use the IS–LM model as an analytical tool, economists must essentially ignore expectations, but ‘we now know that this simplification eliminates key determinants of aggregate demand’ (King, 1993). King advises macroeconomists and policy makers to ignore new Keynesian advertising because, despite the new packaging, the new product is as unsound as the original one (however, see section 7.12 above).

Finally, Paul Davidson (1994) has been very critical of new Keynesian analysis, claiming that ‘there is no Keynesian beef in new Keynesianism’. From Davidson’s Post Keynesian perspective, new Keynesians pay no attention to crucial aspects of Keynes’s monetary theory (see Chapter 8). However, Mankiw (1992) does not regard consistency between new Keynesian analysis and the General Theory, which he describes as ‘an obscure book’, as an important issue.

7.14An Assessment of New Keynesian Economics

How successful have new Keynesian economists been in their quest to develop coherent microfoundations for sticky price models? Barro’s (1989a) main conclusion regarding new Keynesian economics (for which he uses the acronym NUKE) was that, although some of these ideas may prove to be useful as elements in real business cycle models, NUKE models have ‘not been successful in rehabilitating the Keynesian approach’. In sharp contrast, Mankiw and Romer (1991, p. 15) concluded that ‘The new classical argument that the Keynesian assumption of nominal rigidities was incapable of being given theoretical foundations has been refuted.’

Keynesian economics has displayed a remarkable resilience during the past 30 years, given the strength of the theoretical counter-revolutions launched against its essential doctrines, particularly during the period 1968–82. This resilience can be attributed to the capacity of Keynesian analysis to adapt to both theoretical innovations and new empirical findings (see Shaw, 1988; Lindbeck, 1998; Gali, 2002). Not only has Keynesian economics proved capable of absorbing the natural rate hypothesis and expectations-augmented Phillips curve; it has also managed to accommodate the rational expectations hypothesis and build on the insights and methodology of the real business cycle school (Ireland, 2004). This fundamental metamorphosis continues, with new Keynesian theorists rebuilding and refining the foundations of