Snowdon & Vane Modern Macroeconomics

.pdf412 |

Modern macroeconomics |

impossible of solution. This is because nominal auditing and bookkeeping are the only methods invented for principals to control agents in various situations. For example, Leijonhufvud highlights the problems that arise when the national budget for the coming year becomes meaningless when ‘money twelve months hence is of totally unknown purchasing power’. In such situations government departments cannot be held responsible for not adhering to their budgets since the government has lost overall control. ‘It is not just a case of the private sector not being able to predict what the monetary authorities are going to do, the monetary authorities themselves have no idea what the rate of money creation will be next month because of constantly shifting, intense political pressures’ (Snowdon, 2004a; see also Heymann and Leijonhufvud, 1995). Other significant costs arise if governments choose to suppress inflation, leading to distortions to the price mechanism and further significant efficiency losses. Shiller (1997) has also shown that inflation is extremely unpopular among the general public although ‘people have definite opinions about the mechanisms and consequences of inflation and these opinions differ … strikingly between the general public and economists’. To a large extent these differences seem to depend on the finding of Diamond et al. (1997) that ‘money illusion seems to be widespread among economic agents’.

While the impact of inflation rates of less than 20 per cent on the rate of economic growth may be small, it is important to note that small variations in growth rates have dramatic effects on living standards over relatively short historical periods (see Chapter 11, and Fischer, 1993; Barro, 1995; Ghosh and Phillips, 1998; Feldstein, 1999; Temple, 2000; Kirshner, 2001). Ramey and Ramey (1995) also present evidence from a sample of 95 countries that volatility and growth are related; that is, more stable economies normally grow faster. Given that macroeconomic stability and economic growth are positively related (Fischer, 1993), achieving low and stable inflation will be conducive to sustained growth. For example, Taylor, in a series of papers, argues that US growth since the early 1980s (the ‘Great Boom’) was sustained due to lower volatility induced by improved monetary policy (Taylor, 1996, 1997a, 1997b, 1998a, 1998b, 1999).

Recently, Romer and Romer (1999) and Easterly and Fischer (2001) have presented evidence showing that inflation damages the well-being of the poorest groups in society. The Romers find that high inflation and macroeconomic instability are ‘correlated with less rapid growth of average income and lower equality’. They therefore conclude that a low-inflation economic environment is likely to result in higher income for the poor over time due to its favourable effects on long-run growth and income equality, both of which are adversely affected by high and variable inflation. Although expansionary monetary policies can induce a boom and thus reduce poverty, these effects

The new Keynesian school |

413 |

are only temporary. As Friedman (1968a) and Phelps (1968) demonstrated many years ago, expansionary monetary policy cannot create a permanent boom. Thus ‘the typical package of reforms that brings about low inflation and macroeconomic stability will also generate improved conditions for the poor and more rapid growth for all’ (Romer and Romer, 1999).

7.11.2 Monetary regimes and inflation targeting

If a consensus of economists agree that inflation is damaging to economic welfare, it remains to be decided how best to control inflation. Since it is now widely accepted that the primary long-run goal of monetary policy is to control inflation and create reasonable price stability, the clear task for economists is to decide on the exact form of monetary regime to adopt in order to achieve this goal. Monetary regimes are characterized by the use of a specific nominal anchor. Mishkin (1999) defines a nominal anchor as ‘a constraint on the value of domestic money’ or more broadly as ‘a constraint on discretionary policy that helps weaken the time-inconsistency problem’. This helps to solve the inflation bias problem inherent with the use of discretionary demand management policies (Kydland and Prescott, 1977). In practice, during the last 50 years, we can distinguish four types of monetary regime that have operated in market economies; first, exchange rate targeting, for example the UK, 1990–92; second, monetary targeting, for example the UK, 1976–87; third, explicit inflation targeting, for example the UK, 1992 to date; fourth, implicit inflation targeting, for example the USA, in recent years (see Mishkin, 1999; Goodfriend, 2004). While each of these monetary regimes has advantages and disadvantages, in recent years an increasing number of countries have begun to adopt inflation targeting in various forms, combined with an accountable and more transparent independent central bank (see Alesina and Summers, 1993; Fischer, 1995a, 1995b, 1996b; Green, 1996; Bernanke and Mishkin, 1992, 1997; Bernanke and Woodford, 1997; Bernanke et al., 1999; King, 1997a, 1997b; Snowdon, 1997; Svensson, 1997a, 1997b, 1999, 2000; Artis et al., 1998; Haldane, 1998; Vickers, 1998; Mishkin, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2002; Gartner, 2000; Muscatelli and Trecroci, 2000; Piga, 2000; Britton, 2002; Geraats, 2002; Bernanke and Woodford, 2004; see also the interview with Bernanke in Snowdon, 2002a, 2002b).

Following Svensson (1997a, 1997b) and Mishkin (2002), we can view inflation targeting as a monetary regime that encompasses six main elements:

1.the public announcement of medium-term numerical targets for inflation;

2.a firm institutional commitment to price stability (usually a low and stable rate of inflation around 2–3 per cent) as the primary goal of monetary policy; the government, representing society, assigns a loss function to the central bank;

414 |

Modern macroeconomics |

3.an ‘information-inclusive strategy’ where many variables are used for deciding the setting of policy variables;

4.greater transparency and openness in the implementation of monetary policy so as to facilitate better communication with the public; inflation targets are much easier to understand than exchange rate or monetary targets;

5.increased accountability of the central bank with respect to achieving its inflation objectives; the inflation target provides an ex post indicator of monetary policy performance; also, by estimating inflationary expectations relative to the inflation target, it is possible to get a measure of the credibility of the policy;

6.because the use of inflation targeting as a nominal anchor involves comparing the announced target for inflation with the inflation forecast as the basis for making monetary policy decisions, Svensson (1997b) has pointed out that ‘inflation targeting implies inflation forecast targeting’ and ‘the central bank’s inflation forecast becomes the intermediate target’.

The successful adoption of an inflation targeting regime also has certain other key prerequisites. The credibility of inflation targeting as a strategy will obviously be greatly enhanced by having a sound financial system where the central bank has complete instrument independence in order to meet its inflation objectives (see Berger et al., 2001; Piga, 2000). To this end the Bank of England was granted operational independence in May, 1997 (Brown, 1997). It is also crucial that central banks in inflation targeting countries should be free of fiscal dominance. It is highly unlikely that countries with persistent and large fiscal deficits will be able to credibly implement a successful inflation targeting strategy. This may be a particular problem for many developing and transition economies (Mishkin, 2000a). Successful inflation targeting also requires the adoption of a floating exchange rate regime to ensure that the country adopting this strategy maintains independence for its monetary policy. The well-known open economy policy trilemma shows that a country cannot simultaneously maintain open capital markets + fixed exchange rates + an independent monetary policy oriented towards domestic objectives. A government can choose any two of these but not all three simultaneously! If a government wants to target monetary policy towards domestic considerations such as an inflation target, either capital mobility or the exchange rate target will have to be abandoned (see Obstfeld, 1998; Obstfeld and Taylor, 1998; Snowdon, 2004b).

As we noted in Chapter 5, Svensson (1997a) has shown how inflation targeting has emerged as a strategy designed to eliminate the inflation bias inherent in discretionary monetary policies. While Friedman and Kuttner (1996) interpret inflation targeting as a form of monetary rule, Bernanke and

The new Keynesian school |

415 |

Mishkin (1997) prefer to view it as a monetary regime that subjects the central bank to a form of ‘constrained discretion’. Bernanke and Mishkin see inflation targeting as a framework for monetary policy rather than a rigid policy rule. In practice all countries that have adopted inflation targeting have also built an element of flexibility into the target. This flexible approach is supported by Mervyn King (2004), who was appointed Governor of the Bank of England following the retirement of Eddie George in June 2003. King identifies the ‘core of the monetary policy problem’ as being ‘uncertainty about future social decisions resulting from the impossibility and the undesirability of committing successors to any given monetary policy strategy’. These problems make any form of fixed rule undesirable even if it were possible to commit to one because, as King (2004) argues,

The exercise of some discretion is desirable in order that we may learn. The most cogent argument against the adoption of a fixed monetary policy rule is that no rule is likely to remain optimal for long … So we would not want to embed any rule deeply into our decision making structure … Instead, we delegate the power of decision to an institution that will implement policy period by period exercising constrained discretion.

The need for flexibility due to uncertainty is also emphasized by Alan Greenspan, who became Chaiman of the US Federal Reserve in August 1987 (he is due to retire in June 2008). The Federal Reserve’s experiences over the post-war era make it clear that ‘uncertainty is not just a pervasive feature of the monetary policy landscape; it is the defining characteristic of that landscape’ (Greenspan, 2004). Furthermore:

Given our inevitably incomplete knowledge about key structural aspects of an everchanging economy and the sometimes symmetric costs or benefits of particular outcomes, a central bank needs to consider not only the most likely future path for the economy but also the distribution of possible outcomes about that path. The decision-makers then need to reach a judgement about the probabilities, costs, and benefits of the various possible outcomes under alternative choices for policy.

Clearly the setting of interest rates is as much ‘art as science’ (Cecchetti, 2000). The need for flexibility can in part be illustrated by considering a conventional form of the loss function (Lt) assigned to central bankers given by equation (7.16).

|

|

|

1 |

˙ ˙ |

2 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Lt = |

2 |

[Pt − P ) |

|

+ φ |

(Yt − Y ) |

|

], φ > 0 |

|

(7.16) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

˙ |

is the rate of inflation at time period |

||||

In this quadratic social loss function Pt |

|||||||||||

˙ |

* |

is the inflation target, Yt is aggregate output at time t, and Y |

* |

represents |

|||||||

t, P |

|

|

|||||||||

416 |

Modern macroeconomics |

the natural rate or target rate of output. The parameter φ is the relative weight given to stabilizing the output gap. For strict inflation targeting φ = 0, whereas with flexible inflation targeting φ > 0. As Svenssson (1997a) notes, ‘no central bank with an explicit inflation target seems to behave as if it wishes to achieve the target at all cost’. Setting φ = 0 would be the policy stance adopted by those who Mervyn King (1997b) describes as ‘inflation nutters’. Thus all countries that have introduced inflation targeting have built an element of flexibility into the target (Allsopp and Vines, 2000).

What should be the numerical value of the inflation target? Alan Greenspan, currently the most powerful monetary policy maker in the world, has reputedly defined price stability as a situation where people cease to take inflation into account in their decisions. More specifically, Bernanke et al. (1999) come down in favour of a positive value for the inflation target in the range 1–3 per cent. This is supported by Summers (1991b, 1996), Akerlof et al. (1996), and Fischer (1996b). One of the main lessons of the Great Depression, and one that has been repeated in much milder form in Japan during the last decade, is that it is of paramount importance that policy makers ensure that economies avoid deflation (Buiter, 2003b; Eggertsson and Woodford, 2003; Svensson, 2003a). Because the nominal interest rate has a lower bound of zero, any general deflation of prices will cause an extremely damaging increase in real interest rates. Cechetti (1998) argues that the message for inflation targeting strategies is clear, ‘be wary of targets that imply a significant chance of deflation’. It would therefore seem unwise to follow Feldstein’s (1999) recommendation to set a zero inflation target. Akerlof et al. (1996) also support a positive inflation target to allow for relative price changes. If nominal wages are rigid downwards, then an alternative way of engineering a fall in real wages in order to stimulate employment is to raise the general price level via inflation relative to sticky nominal wages. With a flexible and positive inflation target this option is available for the central bank.

Following the UK’s departure from the ERM in September 1992 it became imperative to put in place a new nominal anchor to control inflation. During the post-1945 period we can identify five monetary regimes adopted by the UK monetary authorities, namely, a fixed (adjustable peg) exchange rate regime, 1948–71; a floating exchange rate regime with no nominal anchor, 1971–6; monetary targets, 1976–87; exchange rate targeting (‘shadowing the Deutchmark’ followed by membership of the ERM), 1987–92; and finally inflation targeting, 1992 to date (Balls and O’Donnell, 2002). The credibility of the inflation targeting regime was substantially improved in May 1997 when the Bank of England was given operational independence. This decision, taken by the ‘New Labour’ government, was designed to enhance the administration’s anti-inflation credibility by removing the suspicion that ideo-

The new Keynesian school |

417 |

logical or short-term electoral considerations would in future influence the conduct of stabilization policy (see Chapter 10).

The current UK monetary policy framework encompasses the following main features:

1.A symmetrical inflation target. The targets or goals of policy are set by the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

2.Monthly monetary policy meetings by a nine-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of ‘experts’. To date, current and past membership of the MPC has included many distinguished economists, including Mervyn King, Charles Bean, Steven Nickell, Charles Goodhart, Willem Buiter, Alan Budd, John Vickers, Sushil Wadhami, DeAnne Julius, Christopher Allsopp, Kate Barker and Eddie George.

3.Instrument independence for the central bank. The MPC has responsibility for setting interest rates with the central objective of publication of MPC minutes.

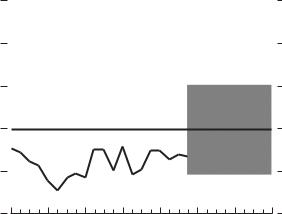

4.Publication of a quarterly Inflation Report which sets forth the Bank of England’s inflation and GDP forecasts. The Bank of England’s inflation forecast is published in the form of a probability distribution presented in the form of a ‘fan chart’ (see Figure 7.13). The Bank’s current objective is to achieve an inflation target of 2 per cent, as measured by the 12month increase in the consumer prices index (CPI). This target was

Percentage increases in prices on a year earlier 5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1999 |

2000 |

01 |

02 |

03 |

04 |

05 |

06 0 |

Figure 7.13 Bank of England inflation report fan chart for February 2004: forecast of CPI inflation at constant nominal interest rates of 4.0 per cent

418 |

Modern macroeconomics |

announced on 10 December 2003. Previously the inflation target was 2.5 per cent based on RPIX inflation (the retail prices index excluding mortgage interest payments).

5.An open letter system. Should inflation deviate from target by more than 1 per cent in either direction, the Governor of the Bank of England, on behalf of the MPC, must write an open letter to the Chancellor explaining the reasons for the deviation of inflation from target, an accommodative approach when confronted by large supply shocks to ease the adverse output and employment consequences in such circumstances (Budd, 1998; Bean, 1998; Treasury, 1999; Eijffinger, 2002b).

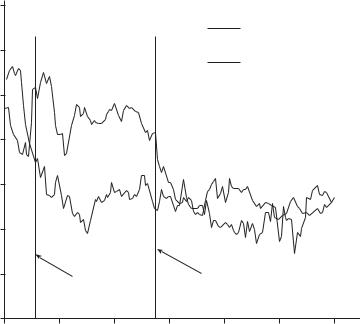

Since 1992 the inflation performance of the UK economy has been very impressive, especially when compared to earlier periods such as the 1970s

% |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Implied inflation |

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

from IGsa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

RPIX inflation rate |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Inflation |

|

Bank |

|

|

|

|

|

target |

|

independence |

|

||

|

|

announced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oct. 91 |

Oct. 93 |

Oct. 95 |

Oct. 97 |

Oct. 99 |

Oct. 01 |

Oct. 03 |

Note: a Implied average expectations from 5 to 10 years ahead, derived from index-linked gilts.

Source: Bank of England, www.bankofengland.co.uk.

Figure 7.14 UK inflation and inflation expectations, October 1991–

October 2003

The new Keynesian school |

419 |

and 1980s when inflation was high and volatile. Figure 7.14 clearly illustrates the dramatic improvement in the UK’s inflation performance since 1992, especially compared to earlier periods (see King, 2004).

While it is too early to tell if this monetary arrangement can deliver lower inflation and greater economic stability over the longer term, especially in a more turbulent world than that witnessed during the 1990s, the evidence from recent years at least gives some cause for optimism, a case of ‘so far so good’ (see Treasury, 1999; Balls and O’Donnell, 2002). However, Ball and Sheridan (2003) argue that there is no evidence that inflation targeting has improved economic performance as measured by inflation, output growth and interest rates. They present evidence that non-inflation-targeting countries have also experienced a decline in inflation during the same period as the inflation targeters, suggesting perhaps that better inflation performance may have been the result of other factors. For example, Rogoff (2003), in noting the fall in global inflation since the early 1980s, identifies the interaction of globalization, privatization and deregulation as important factors, along with better policies and institutions, as major factors contributing to disinflation.

7.11.3 A new Keynesian approach to monetary policy

In two influential papers, Clarida et al. (1999, 2000) set out what they consider to be some important lessons that economists have learned about the conduct of monetary policy. Economists’ research in this field points towards some useful general principles about optimal policy. They identify their approach as new Keynesian because in their model nominal price rigidities allow monetary policy to have non-neutral effects on real variables in the short run, there is a positive short-run relationship between output and inflation (that is, a Phillips curve), and the ex ante real interest rate is negatively related to output (that is, an IS function).

In their analysis of US monetary policy in the period 1960–96 Clarida et al. (2000) show that there is a ‘significant difference in the way that monetary policy was conducted pre-and post-1979’, being relatively well managed after 1979 compared to the earlier period. The key difference between the two periods is the magnitude and speed of response of the Federal Reserve to expected inflation. Under the respective chairmanships of William M. Martin, G. William Miller and Arthur Burns, the Fed was ‘highly accommodative’. In contrast, in the years of Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan, the Fed was much more ‘proactive toward controlling inflation’ (see Romer and Romer, 2002, 2004).

Clarida et al. (2000) conduct their investigation by specifying a baseline policy reaction function of the form given by (7.17):

|

˙ |

t )− |

˙ |

γ E[yt,q Ω| t ] |

(7.17) |

rt = r + β [E(Pt,k | Ω |

P +] |

||||

420 Modern macroeconomics

Here |

r* |

represents the target rate for the Federal Funds (FF) nominal interest |

||

|

t |

˙ |

|

|

rate; |

˙ |

* |

is the |

|

Pt,k |

is the rate of inflation between time periods t and t + k; P |

|

||

inflation target; yt,q measures the average deviation between actual GDP and the target level of GDP (the output gap) between time periods t and t + q; E is the expectations operator; Ω t is the information set available to the policy maker at the time the interest rate is set; and r* is the ‘desired’ nominal FF

rate when both ˙ and y are at their target levels. For a central bank with a

P

quadratic loss function, such as the one given by equation (7.16), this form of policy reaction function (rule) is appropriate in a new Keynesian setting. The policy rule given by (7.17) differs from the well-known ‘Taylor rule’ in that it is forward-looking (see Taylor, 1993, 1998a). Taylor proposed a rule where the Fed reacts to lagged output and inflation whereas (7.17) suggests that the Fed set the FF rate according to their expectation of the future values of inflation and output gap. The Taylor rule is equivalent to a ‘special case’ of equation (7.17) where lagged values of inflation and the output gap provide sufficient information for forecasting future inflation. First recommended at the 1992 Carnegie-Rochester Conference, Taylor’s (1993) policy formula is given by (7.18):

˙ |

˙ ˙ * |

) + r |

* |

(7.18) |

r = P + g(y) + h(P − P |

|

|||

where y is real GDP measured as the percentage deviation from potential GDP;

|

|

|

˙ |

|

|

|

r is the short-term nominal rate of interest in percentage points; P is the rate |

||||||

˙ * |

the target rate of inflation; r |

* |

is the ‘implicit real interest |

|||

of inflation and P |

|

|||||

rate in the central bank’s reaction function’; and the parameters g, h, |

˙ |

* |

and |

|||

P |

|

|||||

r* all have a positive value. With this rule short-term nominal interest rates will rise if output and/or inflation are above their target values and nominal rates will fall when either is below their target value. For a critique of Taylor rules see Svensson (2003b).

In the case of (7.17) the policy maker is able to take into account a broad selection of information about the future path of the economy. In standard macroeconomic models aggregate demand responds negatively to the real rate of interest; that is, higher real rates dampen economic activity and lower real rates stimulate economic activity. From equation (7.17) we can derive

the ‘implied rule’ for the target (ex ante) real rate of interest, rr |

. This is |

||||||||||||

given by equation (7.19): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

* |

+ |

|

˙ |

| Ω |

|

|

˙ * |

] +γ E[yt,q Ω| t ] |

(7.19) |

||

|

rrt = rr |

|

(β −1)[E(Pt,k |

t ) − P |

|||||||||

|

˙ |

| Ω |

˙ * |

], and |

rr |

* |

≡ |

* |

˙ |

* |

is the long-run |

equilib- |

|

Here, rrt ≡ |

rt− [E(Pt,k |

t )− P |

|

r − |

P |

|

|||||||

rium real rate of interest. According to (7.19) the real rate target will respond to changes in the Fed’s expectations about future output and inflation. How-

The new Keynesian school |

421 |

ever, as Clarida et al. point out, the sign of the response of rrt to expected changes in output and inflation will depend on the respective values of the coefficients β and γ. Providing that β > 1 and γ > 0, then the interest rate rule will tend be stabilizing. If β ≤ 1 and γ ≤ 0, then interest rate rules ‘are likely to be destabilising, or, at best, accommodative of shocks’. With β < 1, an increase in expected inflation leads to a decline in the real interest rate, which in turn stimulates aggregate demand thereby exacerbating inflation. During the mid-1970s, the real interest rate in the USA was negative even though inflation was above 10 per cent.

By building on this basic framework, Clarida et al. (2000), in their examination of the conduct of monetary policy in the period 1960–96, find that

the Federal reserve was highly accommodative in the pre-Volcker years: on average, it let the real short-term interest rate decline as anticipated inflation rose. While it raised the nominal rate, it did so by less than the increase in expected inflation. On the other hand, during the Volcker–Greenspan era the Federal Reserve adopted a proactive stance toward controlling inflation: it systematically raised real as well as nominal short-term interest rates in response to higher expected inflation.

During the 1970s, despite accelerating inflation, the FF nominal rate tracked the rate of inflation but for much of the period this led to a zero or negative ex post real rate. There was a visible change in the conduct of monetary policy after 1979 when, following the Volcker disinflation via tight monetary policy, the real rate for most of the 1980s became positive. In recognition of the lag in monetary policy’s impact on economic activity, the new monetary regime involved a pre-emptive response to the build-up of inflationary pressures. As a result of this marked change in the Fed’s policy, inflation was successfully reduced although as a consequence of the disinflation the USA suffered its worst recession since the Great Depression. Unemployment rose from 5.7 per cent in the second quarter of 1979 to 10.7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 1982 (Gordon, 2003).

In their analysis of the change of policy regime at the Fed, Clarida et al. compare the FF rate with the estimated target forward (FWD) value for the interest rate under the ‘Volcker–Greenspan’ rule for the whole period. According to Clarida et al. the estimated rule ‘does a good job’ of capturing the broad movements of the FF rate for the post-1979 sample period.

There seems little doubt that the lower inflation experienced during the past two decades owes a great deal to the more anti-inflationary monetary stance taken by the Fed and other central banks around the world. DeLong (1997) suggests that the inferior monetary policy regime of the pre-Volcker period may have been due to the Fed believing that the natural rate of unemployment was lower than it actually was during the 1970s. Clarida et al. (2000) suggest another possibility. At that time ‘neither the Fed nor the economics profession