Nafziger Economic Development (4th ed)

.pdf

336 Part Three. Factors of Growth

TABLE 10-1. Average Social Returns to Investment in Education

|

Primary |

Secondary |

Higher |

Region |

education |

education |

education |

|

|

|

|

Asia |

16.2 |

11.1 |

11.0 |

Europe/Middle East/North Africa |

15.6 |

9.7 |

9.9 |

Latin America/Caribbean |

17.4 |

12.9 |

12.3 |

Organization for Economic |

8.5 |

9.4 |

8.5 |

Cooperation and Development |

|

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

25.4 |

18.4 |

11.3 |

World |

18.9 |

13.1 |

10.8 |

Note: In all cases, the figures are “social” rates of return: The costs include foregone earnings (what the students could have earned had they not been in school) as well as both public and private outlays; the benefits are measured by income before tax. (The “private” returns to individuals exclude public costs and taxes, and are usually larger.)

Non-OECD.

Source: Psacharopoulos and Patrinos 2002.

2,700,000 (with a network of local affiliated colleges to major universities in each state) costs only $250 per student.2 By contrast, returns to primary education reach a point of diminishing returns, declining as literacy rates increase from LDCs to OECD countries (Table 10-1).

John B. Knight, Richard H. Sabot, and D. C. Hovey (1992:192–205; Knight and Sabot 1990:170–171) argue that studies by Psacharopoulos, often with a collaborator, are based on methodologically flawed estimates. Although average rates of return on primary education were higher than that to secondary education, the marginal rates of returns to the cohort entering into the labor market were lower for primary education than for secondary education. In the 1960s and 1970s, primary graduates were in scarce supply; a primary-school certificate was a passport to a white-collar job. In the 1990s, however, after decades of rapid educational expansion and the displacement of primary graduates by secondary graduates, primary completers are fortunate to get even the most menial blue-collar wage job. As education expands and as secondary completers displace primary completers in many occupations, successive cohorts of workers with primary-school certificates “filter down” into lesser jobs and lower rates of return. However, secondary graduates, who have acquired more occupation-specific human capital, resist the reduction of scarcity rents and the compression of the occupational wage structure with educational expansion. Thus, Knight, Sabot, and Hovey question whether LDCs should place a priority on investment in primary education.

2The returns to investment in primary education are especially high in countries such as Bangladesh, “where mass illiteracy prevails” (U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific 1992:38).

10. Education, Health, and Human Capital |

|

337 |

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

TABLE 10-2. Public Expenditures on Elementary and Higher Education |

|

||||

|

per Student, 1976 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ratio of |

||

|

|

Higher |

|

higher to |

||

|

|

(postsecondary) |

Elementary |

elementary |

||

|

Region |

education |

education |

education |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

3819 |

38 |

100.5 |

|

|

|

South Asia |

117 |

13 |

9.0 |

|

|

|

East Asia |

471 |

54 |

8.7 |

|

|

|

Middle East and North Africa |

3106 |

181 |

17.2 |

|

|

|

Latin America and Caribbean |

733 |

91 |

8.1 |

|

|

|

Industrialized countries |

2278 |

1157 |

2.0 |

|

|

|

U.S.S.R and Eastern Europe |

957 |

539 |

1.8 |

|

|

Note: Figures shown are averages (weighted by enrollment) of costs (in 1976 dollars) in the countries in each region for which data were available.

Source: World Bank 1980i:46.

How do educational differentials in lifetime earnings vary internationally (assuming a 10-percent annual interest rate on future earnings)? In the late 1960s, the ratio of higher educational to primary education earnings in Africa (8–10:1) was much higher than Latin American (4–5:1), Asian (3–6:1), and North American (3:1) ratios. Indeed in Africa, where university and even secondary graduates have been scarce, the premium to graduates of both levels of education (highly subsidized) is high, whereas the premium is low for both levels in North America (Hinchliffe 1975:152–156).3

Noneconomic Benefits of Education

As we have hinted at earlier, schooling is far more than the acquisition of skills for the production of goods and services. Education has both consumer-good and investment-good components. The ability to appreciate literature or to understand the place of one’s society in the world and in history – although they may not help a worker produce steel or grow millet more effectively – are skills that enrich life, and they are important for their own sakes. People may be willing to pay for schooling of this kind even when its economic rate of return is zero or negative.

Some returns to education cannot be captured by increased individual earnings. Literacy and primary education benefit society as a whole. In this situation, in which the social returns to education exceed private returns, there is a strong argument for a public subsidy.

3Pritchett (2001) notes the high individual rates of returns in low-income countries amid low productivity and economic growth, resulting from widespread rent seeking and bribery, declining marginal returns to education from stagnant demand and low quality of education, the absence of externalities from entrepreneurship and social capital, and the large educational ethnic and gender gaps that contribute to low utilization of educated people (ibid.; Nandwa 2004:3).

338 Part Three. Factors of Growth

Education as Screening

It may be inadequate to measure social rates of return to education through the wage, which does not reflect added productivity in imperfectly competitive labor markets. In LDCs, access to high-paying jobs is often limited through educational qualifications. Education may certify an individual’s productive qualities to an employer without enhancing them. In some developing countries, especially in the public sector, the salaries of university and secondary graduates may be artificially inflated and bear little relation to relative productivity. Educational requirements serve primarily to ration access to these inflated salaries. Earnings differences associated with different educational levels would thus overstate the effect of education on productivity.

By contrast, using educational qualifications to screen job applicants is not entirely wasteful and certainly preferable to other methods of selection, such as class, caste, or family connections. Moreover, the wages of skilled labor relative to unskilled labor have steadily declined as the supply of educated labor has grown. Even the public sector is sensitive to supply changes: Relative salaries of teachers and civil servants are not so high in Asia, where educated workers are more abundant, as in Africa, where they are scarcer.

The World Bank, which surveys 17 studies in LDCs that measure increases in annual output based on four years of primary education versus no primary education, tries to eliminate the screening effect by measuring productivity directly rather than wages. All these studies were done in small-scale agriculture, where educational credentials are of little importance. The studies found that, other things being equal, the returns to investment in primary education were as high as those to investment in machines, equipment, and buildings. These studies conjectured that primary education helps people to work for long-term goals, to keep records, to estimate the returns of past activities and the risks of future ones, and to obtain and evaluate information about changing technology. All in all, these studies of farmer productivity demonstrate that investment in education pays off in some sectors even when educational qualifications are not used as screening devices.4

M. Boissiere’s,` J. B. Knight’s, and R. H. Sabot’s (1985:1016–1030) study in Kenya and Tanzania, which separates skills learned in school from its screening effect, shows that earning ability increases substantially with greater literacy and numeracy (as measured by tests given by researchers), both in manual and nonmanual jobs. These skills enable mechanics, machinists, and forklift drivers, as well as accountants, clerks, and secretaries, to do a better job. But cognitive skills, especially literacy and numeracy, are not certified by schooling but discovered on the job by the employer, who is willing to pay for them by giving a wage premium over time. Earnings do

4See, however, Schultz (1975:827–846), who differentiates between static technology, in which there are no returns to education, and an agricultural economy experiencing dynamic changes in technology, in which education provides returns. Schumpeter’s theory of the entrepreneur (Chapter 13) is one explanation of these dynamics.

The next three sections rely on World Bank (1980i:46–53); Bruton (1965:205–221); Boissiere, Knight, and Sabot (1985:1016–1030); and Nafziger (1988:133–135).

10. Education, Health, and Human Capital |

339 |

TABLE 10-3. Public Education Spending per Household (in dollars)

|

|

Malaysia, 1974b |

|

Colombia, 1974c |

||

Income groupa |

Primary |

Presecondary |

Primary |

University |

||

Poorest 20 percent |

135 |

4 |

|

48 |

1 |

|

Richest 20 percent |

45 |

53 |

|

9 |

46 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

a |

Households ranked by income per person. |

|

|

|||

b |

Federal costs per household. |

|

|

|

|

|

c |

Subsidies per household. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: World Bank 1980i:50.

not, however, increase much with increased reasoning ability (measured by Raven’s Progressive Matrices’ pictorial pattern matching, for which literacy and numeracy provide no advantage) or increased years of school.

In both countries, learning school lessons, not just attending school and receiving certification, substantially affects performance and earnings in work. However, earning differences between primary and secondary graduates could reflect screening or alternatively unmeasured noncognitive skills acquired in secondary education. Research in countries at other levels of economic development is essential before we can generalize about the effects of screening and cognitive achievement.

Education and Equality

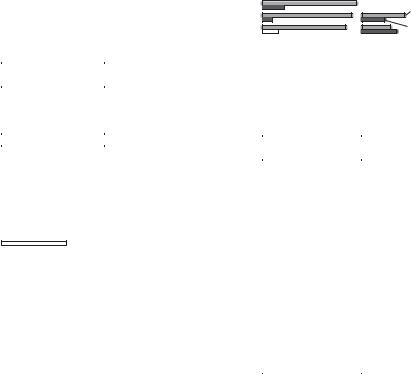

The student who attends school receives high rates of return to what his or her family spends. Yet poor families who might be willing to borrow for more education usually cannot. A simple alternative is for government to reduce the direct costs of education by making public schooling, especially basic primary education, available and free. Expanding primary education reduces income inequality and favorably affects equality of opportunity. As primary schooling expands, children in rural areas, the poorest urban children, and girls will all have more chance of going to school. In general, public expenditures on primary education redistribute income toward the poor, who have larger families and almost no access to private schooling (Clarke 1992; World Bank 1980i:46–53; World Bank 1993a:197). Public spending on secondary and higher education, by contrast, redistributes income to the rich, as poor children have little opportunity to benefit from it (Table 10-3).

The links among parental education, income, and ability to provide education of quality mean educational inequalities are likely to be transmitted from one generation to another. Public primary school, whereas disproportionately subsidizing the poor, still costs the poor to attend. Moreover, access to secondary and higher education is highly correlated with parental income and education. In Kenya and Tanzania, those from a high socioeconomic background are more likely to attend high-cost primary schools, with more public subsidy; better teachers, equipment, and laboratories; and higher school-leaving examination scores; which admit them to the

340 Part Three. Factors of Growth

10. Education, Health, and Human Capital |

341 |

best secondary schools and the university. The national secondary schools, which receive more government aid and thus charge lower fees, take only 5 percent of primary school graduates. Additionally, the explicit private cost for secondary school graduates to attend the university (highly subsidized) is low, and the private benefit is high. Yet this cost (much opportunity cost) of secondary and higher education is still often a barrier to the poor. Moreover, those with affluent and educated parents can not only finance education more easily but also are more likely to have the personal qualities, good connections, and better knowledge of opportunities to receive higher salaries and nonmanual jobs. Not surprisingly, Tony Addison and Aminur Rahman (2003:94) find that the underlying cause of unequal educational and other public spending “is that economic power and associated wealth provide the affluent with a disproportionate influence over the political process, and therefore over expenditure allocation.” The rural poor are less well organized and lack the resources to lobby. Climbing the educational ladder in LDCs depends on income as well as achievement.

In low-income countries in 2000–01, primary enrollment of girls as a percentage of girls age 6–11 years was 69 percent compared to the comparable ratio for boys of 79 percent; for middle-income countries, the corresponding figures were 93 to 93 percent. Sub-Saharan Africa’s primary ratio was 56 percent compared to 64 percent for boys, and South Asia’s 72 percent compared to 86 percent for boys (U.N. Development Program 2003:121). For secondary and university levels, the gender ratios are about the same or less (Nafziger 1997:276). Even if girls never enter the labor force, educating them may be one of the best investments a country can make in future economic welfare. Studies indicate clearly that educating girls substantially improves household nutrition and reduces fertility and child mortality (U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific 1992b:16–19). Yet, in most parts of the developing world, especially South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, the educational bias in favor of male enrollment is pronounced (ibid., 1992). Parents view education for their daughters as less useful than for their sons. Frequently, they fear that education will harm a daughter’s marriage prospects or domestic life. A girl’s education may result in fewer economic benefits, especially if she faces job discrimination, marries early and stops working, or moves to her husband’s village. However, educating her does increase the opportunity for paid employment, and families waste no time in educating their daughters when cultural change reduces the bias against woman in the labor market.

Educational options will widen as LDCs increase their investment in telecommunications. The electronic and video media offer extensive future opportunities for enhanced schooling, learning, and continuing education, as discussed later.

←

FIGURE 10-1. The Poor Are Less Likely to Start School, More Likely to Drop Out. Percentage of 15to 19-year-olds who have completed each grade or higher. Notes: The bold grade number denotes the end of the primary cycle. Fifths based on asset index quintiles. Source: World Bank 2004i:21.

342 Part Three. Factors of Growth

Education and Political Discontent

The World Bank (1996c) shows that, on average, low-income countries, especially sub-Saharan Africa, spend substantially more on education for households in the richest quintiles than those in the poorest ones. Although secondary and (especially) university education is highly subsidized, the private cost is still often a barrier to the poor. Providing free, universal primary education is the most effective policy for reducing the educational inequality that contributes to income inequality and political discontent. Near universal primary education in Kenya, Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, and Zambia have dampened some discontent in these countries, whereas the low rates of primary school enrolment in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Angola, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo DRC, Somalia, and Sudan have perpetuated class, ethnic, and regional divisions and grievances in educational and employment opportunities.

Still, virtually universal basic education is not a panacea. In Sri Lanka, with continuing high enrollment rates in primary and secondary school, the majority Sinhalese perception of Tamil economic success as a threat to their own economic opportunities increased during the period of slow growth and high unemployment after independence in 1948. This perception contributed to governmental policies of educational, language, and employment discrimination against Tamils, beginning in the mid-1950s, which contributed to the Sri Lankan civil war of the last quarter of the 20th century. Thus, in Sri Lanka, educational policy favored the majority community.

Generally, however, expanding educational opportunities for low-income minority regions and communities can reduce social tension and political instability. Politically, the support for expansion in education, especially basic schooling, can come from educators, peasant and working-class constituents whose children lack access to education, and nationalists who recognize the importance of universal literacy for national unity and labor skills for modernization. Examples of these coalitions supporting universal basic education include Meiji Japan (Nafziger 1995) and Africa in the 1960s.5

Secondary and Higher Education

Although primary education in LDCs is important, secondary and higher education should not be abandoned. Despite the high numbers of educated unemployed in some developing countries, especially among humanities and social sciences (but not economics!) graduates,6 there are some severe shortages of skilled people. Although

5 Nafziger (1988:127–139), on “Maintaining Class: The Role of Education,” discusses the political barriers to universal quality education.

6Psacharopoulos (1985:590–591, 603–604) indicates that the average returns to human capital investment for 14 DCs and LDCs are higher for economics than six other fields, which suggests that unemployment rates for economic graduates are also low.

10. Education, Health, and Human Capital |

343 |

Guinea 1994

India (UP) 1996

Armenia 1999

Ecuador 1998

Ghana 1994

India 1996

Côte d'lvoire 1995

Madagascar 1993

Tanzania 1993

Indonesia 1990

Vietnam 1993

Bangladesh 2000

Bulgaria 1995

Kenya (rural) 1992

Sri Lanka 1996

Nicaragua 1998

South Africa 1994

Colombia 1992

Costa Rica 1992

Honduras 1995

Argentina 1991

Tajikistan 1999

Moldova 2001

Brazil (NE&SE) 1997

Georgia 2000

Guyana 1994

All health spending |

Primary health only |

All education spending |

Primary education only |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nepal 1996 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Guinea 1994 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Madagascar 1994 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kosovo 2000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FYR Macedonia 1996 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tanzania 1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

South Africa 1994 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Côte d'lvoire 1995 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nicaragua 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lao PDR 1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Guyana 1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bangladesh 2000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Uganda 1992–93 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indonesia 1989 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cambodia 1997 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pakistan 1991 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Armenia 1996 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kyrgyz Rep. 1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kazakhstan 1996 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brazil (NE&SE) 1997 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malawi 1995 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ecuador 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Morocco 1999 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peru 1994 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yemen 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Azerbaijan 2001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

20 |

|

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vietnam 1998 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent |

|

Mexico 1996 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Panama 1997

Kenya 1992

Ghana 1992

Costa Rica 2001

Romania 1994

Jamaica 1998

Colombia 1992

Mauritania 1996

Richest fifth

Poorest fifth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

|

|

40 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 10-2. Richer People Often Benefit More from Public Spending on Health and Education. Share of public spending on health and education going to the richest and poorest fifths. Note: Figure reports most recent available data. Source: World Bank 2004i:39.

these shortages vary from country to country, quite often the shortages are in vocational, technical, and scientific areas.7

One possible approach to reduce the unit cost of training skilled people is to use more career in-service or on-the-job training. The following discussion suggests other ways.

In most countries, government subsidizes students beyond the primary level. Yet the families of these students are generally much better off than the national average (Figures 10-1 and 10-2). For example, in Tunisia, the proportion of children from

7The U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (1992a:38–51) notes substantial shortages of people with scientific and technological education in China and South Asia. Farmers and informal-sector entrepreneurs and workers in rural areas especially benefit from simple technical training.

344Part Three. Factors of Growth

higher income groups is nine times larger in universities than in primary schools. These students should probably be charged tuition and other fees to cover the costs of their higher education, as its individual rewards are large. Charging these richer students allows government to spend more on poorer children, who can be granted scholarships. These policies may be difficult to implement. Parents of postprimary children are usually politically influential and will probably resist paying greater educational costs.

Education via Electronic Media

Distance learning through teleconferencing and computers can dramatically reduce the cost of continuing education and secondary and higher education, including teacher training. To be sure, as pointed out in Chapter 11, the digital divide excludes much of Asia, Latin America, and especially Africa from the benefits of computerization and the Internet. In 2000, the Economist estimated that only 3 million of some 360 million Internet users are in Africa.

Jamil Salmi, the author of a World Bank report on education, states that university or “tertiary education drives a country’s future.” His coauthored report urges policy makers to take advantage of the opportunities of university education, combined with new knowledge networks and technologies, in increasing productivity. The University of Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, expanded opportunities for higher education by relying more on distance learning, often cheaper than building additional universities (World Bank 2002a; World Bank Development News, “Developing Countries Need Quality Higher Education: World Bank Report.” December 5, 2002).

Mauritania, a Saharan country with a population of three million, uses distance learning to stretch its educational dollars. Its only university, the University of Nouakchott, “is trying to deliver high-quality education from North America via teleconferencing and the Internet through a branch of the African Virtual University” (del Castillo 2002). In 2002, students acquired training via a one-way system via satellite, with local lecturers providing interaction with the students. Unlike in the West, the university is designed not to serve urban workers or rural people but to enhance instruction for traditional college students, where faculty and other highly-qualified people are scarce (ibid.).

The World Bank, in cooperation with local nongovernmental organizations and national governments, provides educational resources for LDCs, especially in Africa. The Bank and partners have provided an Africa Live Data Base, Connectivity for the Poor to develop local networks (Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique) with access to global knowledge sources, the Global Distance Learning Network with distance learning centers in LDCs to facilitate training for professionals worldwide, the African Virtual University (AVU) to offer degree programs in science, engineering, and continuing education via satellite, and World Links, a school-to-school connectivity program among 64 secondary schools in Africa, linked via the Internet with DC schools (World Bank Group in Africa 2000).

10. Education, Health, and Human Capital |

345 |

Distance learning, as well as correspondence courses for people in remote areas, can dramatically reduce the cost of some postprimary schooling. Where computerized and Internet-based courses are feasible, they can usually be provided at a fraction of the cost of traditional schools, saving expensive infrastructure and buildings, and allowing would-be students to earn income while continuing their education.

In many instances, LDCs can reduce the number of university specializations, relying instead on foreign universities for specialized training in fields in which few students and expensive equipment lead to excessive costs per person. However, care must be taken to prevent either a substantial brain drain from LDCs to DCs (more on this later) or a concentration of foreign-educated children among the rich and influential.

Planning for Specialized Education and Training

The following three skill categories require little or no specific training. The people having these skills move readily from one type of occupation to another.

1.The most obvious category comprises skills simple enough to be learned by short observation of someone performing the task. Swinging an ax, pulling weeds by hand, or carrying messages are such easily acquired skills that educational planners can ignore them.

2.Some skills require rather limited training (perhaps a year or less) that can best be provided on the job. These include learning to operate simple machines, drive trucks, and perform some construction jobs.

3.Another skill category requires little or no specialized training but considerable general training – at least secondary and possible university education. Many administrative and organizational jobs, especially in the civil service, require a good general educational background, as well as sound judgment and initiative. Developing these skills means more formal academic training than is required in the two previous categories.

We have already discussed how public expenditures are best allocated among primary, secondary, and postsecondary education to ensure these skill levels, but we add that highly specialized training and education are usually not essential in these skill categories.