546 |

PART NINE THE REAL ECONOMY IN THE LONG RUN |

Because it has accumulated over so many years, this fall in productivity growth of 1.9 percentage points has had a large effect on incomes. If this slowdown had not occurred, the income of the average American would today be about 60 percent higher.

The slowdown in economic growth has been one of the most important problems facing economic policymakers. Economists are often asked what caused the slowdown and what can be done to reverse it. Unfortunately, despite much research on these questions, the answers remain elusive.

Two facts are well established. First, the slowdown in productivity growth is a worldwide phenomenon. Sometime in the mid-1970s, economic growth slowed not only in the United States but also in other industrial countries, including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. Although some of these countries have had more rapid growth than the United States, all of them have had slow growth compared to their own past experience. To explain the slowdown in U.S. growth, therefore, it seems necessary to look beyond our borders.

Second, the slowdown cannot be traced to those factors of production that are most easily measured. Economists can measure directly the quantity of physical capital that workers have available. They can also measure human capital in the form of years of schooling. It appears that the slowdown in productivity is not primarily attributable to reduced growth in these inputs.

Technology appears to be one of the few remaining culprits. That is, having ruled out most other explanations, many economists attribute the slowdown in economic growth to a slowdown in the creation of new ideas about how to produce goods and services. Because the quantity of “ideas” is hard to measure, this explanation is difficult to confirm or refute.

In some ways, it is odd to say that the last 25 years have been a period of slow technological progress. This period has witnessed the spread of computers across the economy—an historic technological revolution that has affected almost every industry and almost every firm. Yet, for some reason, this change has not yet been reflected in more rapid economic growth. As economist Robert Solow put it, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

What does the future of economic growth hold? An optimistic scenario is that the computer revolution will rejuvenate economic growth once these new machines are integrated into the economy and their potential is fully understood. Economic historians note that the discovery of electricity took many decades to have a large impact on productivity and living standards because people had to figure out the best ways to use the new resource. Perhaps the computer revolution will have a similar delayed effect. Some observers believe this may be starting to happen already, for productivity growth did pick up a bit in the late 1990s. It is still too early to say, however, whether this change will persist.

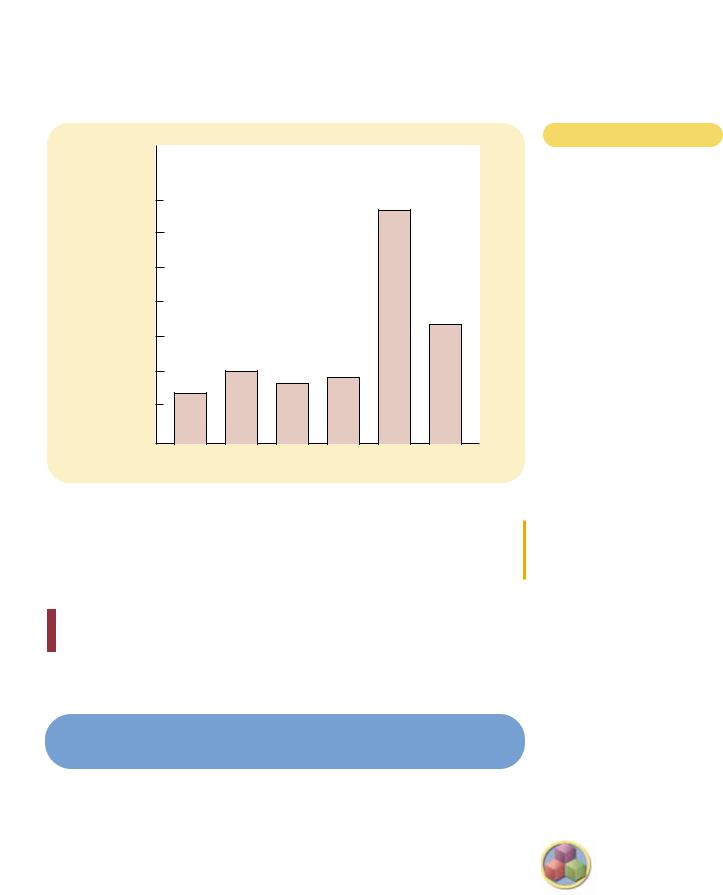

A more pessimistic scenario is that, after a period of rapid scientific and technological advance, we have entered a new phase of slower growth in knowledge, productivity, and incomes. Data from a longer span of history seem to support this conclusion. Figure 24-2 shows the average growth of real GDP per person in the developed world going back to 1870. The productivity slowdown is apparent in the last two entries: Around 1970, the growth rate slowed from 3.7 to 2.2 percent. But compared to earlier periods of history, the anomaly

CHAPTER 24 PRODUCTION AND GROWTH |

547 |

Growth Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(percent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

per year) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1870– |

1890– |

1910– |

1930– |

1950– |

1970– |

|

1890 |

1910 |

1930 |

1950 |

1970 |

1990 |

Figur e 24-2

THE GROWTH IN REAL GDP

PER PERSON. This figure shows the average growth rate of real GDP per person for 16 advanced economies, including the major countries of Europe, Canada, the United States, Japan, and Australia. Notice that the growth rate rose substantially after 1950 and then fell after 1970.

SOURCE: Robert J. Barro and Xavier Sala-i- Martin, Economic Growth (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995), p. 6.

is not the slow growth of recent years but rather the rapid growth during the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps the decades after World War II were a period of unusually rapid technological advance, and growth has slowed down simply because technological progress has returned to a more normal rate.

QUICK QUIZ: Describe three ways in which a government policymaker can try to raise the growth in living standards in a society. Are there any drawbacks to these policies?

CONCLUSION:

THE IMPORTANCE OF LONG-RUN GROWTH

In this chapter we have discussed what determines the standard of living in a nation and how policymakers can endeavor to raise the standard of living through policies that promote economic growth. Most of this chapter is summarized in one of the Ten Principles of Economics: A country’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services. Policymakers who want to encourage growth in standards of living must aim to increase their nation’s productive ability by encouraging rapid accumulation of the factors of production and ensuring that these factors are employed as effectively as possible.

548 |

PART NINE THE REAL ECONOMY IN THE LONG RUN |

|

|

|

|

IN THE NEWS

A Solution to

Africa’s Problems

with the IMF, the World Bank, donors, and creditors.

What a shame. So many good ideas, so few results. Output per head fell 0.7 percent between 1978 and 1987, and 0.6 percent during 1987–1994. Some growth is estimated for 1995 but only at 0.6 percent—far below the fastergrowing developing countries. . . .

The IMF and World Bank would be absolved of shared responsibility for slow growth if Africa were structurally incapable of growth rates seen in other parts of the world or if the continent’s low growth were an impenetrable mystery. But Africa’s growth rates are not huge mysteries. The evidence on cross-country growth suggests that Africa’s chronically low growth can be explained by standard economic variables linked to identifiable (and remediable) policies. . . .

Studies of cross-country growth show that per capita growth is related to:

• the initial income level of the country, with poorer countries tending to grow faster than richer countries;

•the extent of overall market orientation, including openness to trade, domestic market liberalization, private rather than state ownership, protection of private property rights, and low marginal tax rates;

•the national saving rate, which in turn is strongly affected by the government’s own saving rate; and

•the geographic and resource structure of the economy. . . .

These four factors can account broadly for Africa’s long-term growth predicament. While it should have grown faster than other developing areas because of relatively low income per head (and hence larger opportunity for “catch-up” growth), Africa grew more slowly. This was mainly because of much

Economists differ in their views of the role of government in promoting economic growth. At the very least, government can lend support to the invisible hand by maintaining property rights and political stability. More controversial is whether government should target and subsidize specific industries that might be

CHAPTER 24 PRODUCTION AND GROWTH |

549 |

|

|

|

|

higher trade barriers; excessive tax rates; lower saving rates; and adverse structural conditions, including an unusually high incidence of inaccessibility to the sea (15 of 53 countries are landlocked). . . .

If the policies are largely to blame, why, then, were they adopted? The historical origins of Africa’s antimarket orientation are not hard to discern. After almost a century of colonial depredations, African nations understandably if erroneously viewed open trade and foreign capital as a threat to national sovereignty. As in Sukarno’s Indonesia, Nehru’s India, and Peron’s Argentina, “self sufficiency” and “state leadership,” including state ownership of much of industry, became the guideposts of the economy. As a result, most of Africa went into a largely self-imposed economic exile. . . .

Adam Smith in 1755 famously remarked that “little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degrees of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and tolerable administration of justice.” A growth agenda need not be long and complex. Take his points in turn.

Peace, of course, is not so easily guaranteed, but the conditions for peace on the continent are better than today’s ghastly headlines would suggest. Several of the large-scale conflicts that have ravaged the continent are over or nearly so. . . . The ongoing disasters, such as in Liberia, Rwanda and Somalia, would be

better contained if the West were willing to provide modest support to Africanbased peacekeeping efforts.

“Easy taxes” are well within the ambit of the IMF and World Bank. But here, the IMF stands guilty of neglect, if not malfeasance. African nations need simple, low taxes, with modest revenue targets as a share of GDP. Easy taxes are most essential in international trade, since successful growth will depend, more than anything else, on economic integration with the rest of the world. Africa’s largely self-imposed exile from world markets can end quickly by cutting import tariffs and ending export taxes on agricultural exports. Corporate tax rates should be cut from rates of 40 percent and higher now prevalent in Africa, to rates between 20 percent and 30 percent, as in the outward-oriented East Asian economies. . . .

Adam Smith spoke of a “tolerable” administration of justice, not perfect justice. Market liberalization is the primary key to strengthening the rule of law. Free trade, currency convertibility and automatic incorporation of business vastly reduce the scope for official corruption and allow the government to focus on the real public goods—internal public order, the judicial system, basic public health and education, and monetary stability. . . .

All of this is possible only if the government itself has held its own spending to the necessary minimum. The Asian economies show how to function with

government spending of 20 percent of GDP or less (China gets by with just 13 percent). Education can usefully absorb around 5 percent of GDP; health, another 3 percent; public administration, 2 percent; the army and police, 3 percent. Government investment spending can be held to 5 percent of GDP but only if the private sector is invited to provide infrastructure in telecommunications, port facilities, and power. . . .

This fiscal agenda excludes many popular areas for government spending. There is little room for transfers or social spending beyond education and health (though on my proposals, these would get a hefty 8 percent of GDP). Subsidies to publicly owned companies or marketing boards should be scrapped. Food and housing subsidies for urban workers cannot be financed. And, notably, interest payments on foreign debt are not budgeted for. This is because most bankrupt African states need a fresh start based on deep debt-reduction, which should be implemented in conjunction with far-reaching domestic reforms.

Source: Economist, June 29, 1996, pp. 19–21.

especially important for technological progress. There is no doubt that these issues are among the most important in economics. The success of one generation’s policymakers in learning and heeding the fundamental lessons about economic growth determines what kind of world the next generation will inherit.

554 |

PART NINE THE REAL ECONOMY IN THE LONG RUN |

financial system

the group of institutions in the economy that help to match one person’s saving with another person’s investment

There are various ways for you to finance these capital investments. You could borrow the money, perhaps from a bank or from a friend or relative. In this case, you would promise not only to return the money at a later date but also to pay interest for the use of the money. Alternatively, you could convince someone to provide the money you need for your business in exchange for a share of your future profits, whatever they might happen to be. In either case, your investment in computers and office equipment is being financed by someone else’s saving.

The financial system consists of those institutions in the economy that help to match one person’s saving with another person’s investment. As we discussed in the previous chapter, saving and investment are key ingredients to long-run economic growth: When a country saves a large portion of its GDP, more resources are available for investment in capital, and higher capital raises a country’s productivity and living standard. The previous chapter, however, did not explain how the economy coordinates saving and investment. At any time, some people want to save some of their income for the future, and others want to borrow in order to finance investments in new and growing businesses. What brings these two groups of people together? What ensures that the supply of funds from those who want to save balances the demand for funds from those who want to invest?

This chapter examines how the financial system works. First, we discuss the large variety of institutions that make up the financial system in our economy. Second, we discuss the relationship between the financial system and some key macroeconomic variables—notably saving and investment. Third, we develop a model of the supply and demand for funds in financial markets. In the model, the interest rate is the price that adjusts to balance supply and demand. The model shows how various government policies affect the interest rate and, thereby, society’s allocation of scarce resources.

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN THE U.S. ECONOMY

At the broadest level, the financial system moves the economy’s scarce resources from savers (people who spend less than they earn) to borrowers (people who spend more than they earn). Savers save for various reasons—to put a child through college in several years or to retire comfortably in several decades. Similarly, borrowers borrow for various reasons—to buy a house in which to live or to start a business with which to make a living. Savers supply their money to the financial system with the expectation that they will get it back with interest at a later date. Borrowers demand money from the financial system with the knowledge that they will be required to pay it back with interest at a later date.

The financial system is made up of various financial institutions that help coordinate savers and borrowers. As a prelude to analyzing the economic forces that drive the financial system, let’s discuss the most important of these institutions. Financial institutions can be grouped into two categories—financial markets and financial intermediaries. We consider each category in turn.