524 |

PART EIGHT THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS |

changes in interest rates, it will be important for us to keep in mind the distinction between real and nominal interest rates.

QUICK QUIZ: Henry Ford paid his workers $5 a day in 1914. If the consumer price index was 10 in 1914 and 166 in 1999, how much was the Ford paycheck worth in 1999 dollars?

CONCLUSION

“A nickel ain’t worth a dime anymore,” baseball player Yogi Berra once quipped. Indeed, throughout recent history, the real values behind the nickel, the dime, and the dollar have not been stable. Persistent increases in the overall level of prices have been the norm. Such inflation reduces the purchasing power of each unit of money over time. When comparing dollar figures from different times, it is important to keep in mind that a dollar today is not the same as a dollar 20 years ago or, most likely, 20 years from now.

This chapter has discussed how economists measure the overall level of prices in the economy and how they use price indexes to correct economic variables for the effects of inflation. This analysis is only a starting point. We have not yet examined the causes and effects of inflation or how inflation interacts with other economic variables. To do that, we need to go beyond issues of measurement. Indeed, that is our next task. Having explained how economists measure macroeconomic quantities and prices in the past two chapters, we are now ready to develop the models that explain long-run and short-run movements in these variables.

Summar y

The consumer price index shows the cost of a basket of goods and services relative to the cost of the same basket in the base year. The index is used to measure the overall level of prices in the economy. The percentage change in the consumer price index measures the inflation rate.

The consumer price index is an imperfect measure of the cost of living for three reasons. First, it does not take into account consumers’ ability to substitute toward goods that become relatively cheaper over time. Second, it does not take into account increases in the purchasing power of the dollar due to the introduction of new goods. Third, it is distorted by unmeasured changes in the quality of goods and services. Because of these measurement problems, the CPI overstates annual inflation by about 1 percentage point.

Although the GDP deflator also measures the overall level of prices in the economy, it differs from the consumer price index because it includes goods and services produced rather than goods and services consumed. As a result, imported goods affect the consumer price index but not the GDP deflator. In addition, whereas the consumer price index uses a fixed basket of goods, the GDP deflator automatically changes the group of goods and services over time as the composition of GDP changes.

Dollar figures from different points in time do not represent a valid comparison of purchasing power. To compare a dollar figure from the past to a dollar figure today, the older figure should be inflated using a price index.

530 |

PART NINE THE REAL ECONOMY IN THE LONG RUN |

greater economic prosperity than did his or her parents, grandparents, and greatgrandparents.

Growth rates vary substantially from country to country. In some East Asian countries, such as Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, average income has risen about 7 percent per year in recent decades. At this rate, average income doubles every ten years. These countries have, in the length of one generation, gone from being among the poorest in the world to being among the richest. By contrast, in some African countries, such as Chad, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, average income has been stagnant for many years.

What explains these diverse experiences? How can the rich countries be sure to maintain their high standard of living? What policies should the poor countries pursue to promote more rapid growth in order to join the developed world? These are among the most important questions in macroeconomics. As economist Robert Lucas put it, “The consequences for human welfare in questions like these are simply staggering: Once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.”

In the previous two chapters we discussed how economists measure macroeconomic quantities and prices. In this chapter we start studying the forces that determine these variables. As we have seen, an economy’s gross domestic product (GDP) measures both the total income earned in the economy and the total expenditure on the economy’s output of goods and services. The level of real GDP is a good gauge of economic prosperity, and the growth of real GDP is a good gauge of economic progress. Here we focus on the long-run determinants of the level and growth of real GDP. Later in this book we study the short-run fluctuations of real GDP around its long-run trend.

We proceed here in three steps. First, we examine international data on real GDP per person. These data will give you some sense of how much the level and growth of living standards vary around the world. Second, we examine the role of productivity—the amount of goods and services produced for each hour of a worker’s time. In particular, we see that a nation’s standard of living is determined by the productivity of its workers, and we consider the factors that determine a nation’s productivity. Third, we consider the link between productivity and the economic policies that a nation pursues.

ECONOMIC GROWTH AROUND THE WORLD

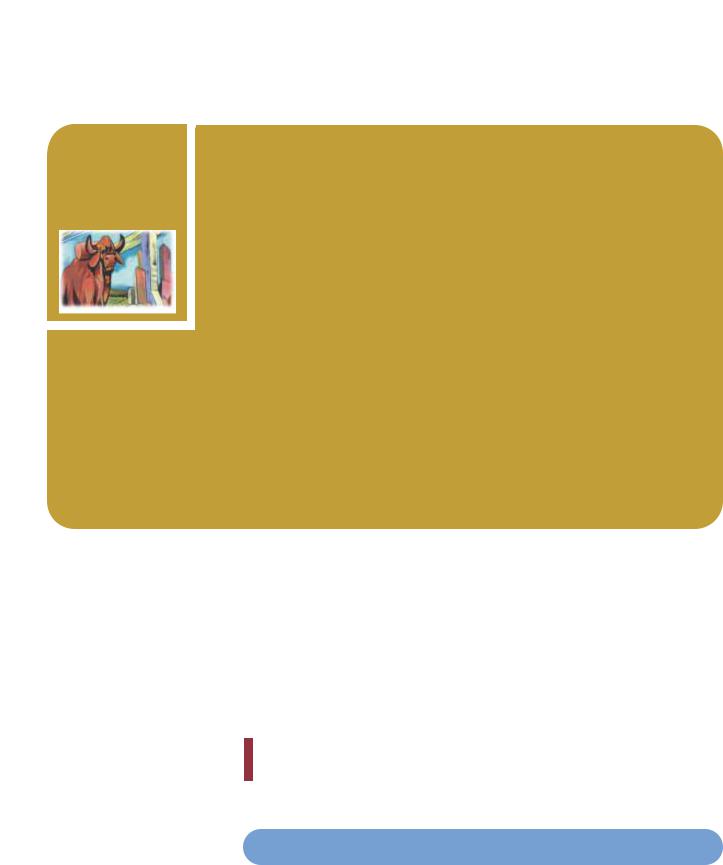

As a starting point for our study of long-run growth, let’s look at the experiences of some of the world’s economies. Table 24-1 shows data on real GDP per person for 13 countries. For each country, the data cover about a century of history. The first and second columns of the table present the countries and time periods. (The time periods differ somewhat from country to country because of differences in data availability.) The third and fourth columns show estimates of real GDP per person about a century ago and for a recent year.

The data on real GDP per person show that living standards vary widely from country to country. Income per person in the United States, for instance, is about 8 times that in China and about 15 times that in India. The poorest countries have average levels of income that have not been seen in the United States for many

CHAPTER 24 PRODUCTION AND GROWTH |

531 |

|

|

REAL GDP PER PERSON |

REAL GDP PER PERSON |

GROWTH RATE |

COUNTRY |

PERIOD |

AT BEGINNING OF PERIODa |

AT END OF PERIODa |

PER YEAR |

|

|

|

|

|

Japan |

1890–1997 |

$1,196 |

$23,400 |

2.82% |

Brazil |

1900–1997 |

619 |

6,240 |

2.41 |

Mexico |

1900–1997 |

922 |

8,120 |

2.27 |

Germany |

1870–1997 |

1,738 |

21,300 |

1.99 |

Canada |

1870–1997 |

1,890 |

21,860 |

1.95 |

China |

1900–1997 |

570 |

3,570 |

1.91 |

Argentina |

1900–1997 |

1,824 |

9,950 |

1.76 |

United States |

1870–1997 |

3,188 |

28,740 |

1.75 |

Indonesia |

1900–1997 |

708 |

3,450 |

1.65 |

India |

1900–1997 |

537 |

1,950 |

1.34 |

United Kingdom |

1870–1997 |

3,826 |

20,520 |

1.33 |

Pakistan |

1900–1997 |

587 |

1,590 |

1.03 |

Bangladesh |

1900–1997 |

495 |

1,050 |

0.78 |

|

|

|

|

|

aReal GDP is measured in 1997 dollars.

SOURCE: Robert J. Barro and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Economic Growth (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995), tables 10.2 and 10.3; World Development Report 1998/99, table 1; and author’s calculations.

THE VARIETY OF GROWTH EXPERIENCES

Table 24-1

decades. The typical citizen of China in 1997 had about as much real income as the typical American in 1870. The typical person in Pakistan in 1997 had about onehalf the real income of a typical American a century ago.

The last column of the table shows each country’s growth rate. The growth rate measures how rapidly real GDP per person grew in the typical year. In the United States, for example, real GDP per person was $3,188 in 1870 and $28,740 in 1997. The growth rate was 1.75 percent per year. This means that if real GDP per person, beginning at $3,188, were to increase by 1.75 percent for each of 127 years, it would end up at $28,740. Of course, real GDP per person did not actually rise exactly 1.75 percent every year: Some years it rose by more and other years by less. The growth rate of 1.75 percent per year ignores short-run fluctuations around the long-run trend and represents an average rate of growth for real GDP per person over many years.

The countries in Table 24-1 are ordered by their growth rate from the most to the least rapid. Japan tops the list, with a growth rate of 2.82 percent per year. A hundred years ago, Japan was not a rich country. Japan’s average income was only somewhat higher than Mexico’s, and it was well behind Argentina’s. To put the issue another way, Japan’s income in 1890 was less than India’s income in 1997. But because of its spectacular growth, Japan is now an economic superpower, with average income only slightly behind that of the United States. At the bottom of the list of countries is Bangladesh, which has experienced growth of only 0.78 percent per year over the past century. As a result, the typical resident of Bangladesh continues to live in abject poverty.

Because of differences in growth rates, the ranking of countries by income changes substantially over time. As we have seen, Japan is a country that has risen

532 |

PART NINE THE REAL ECONOMY IN THE LONG RUN |

F Y I

The Magic of

Compounding

and the

Rule of 70

It may be tempting to dismiss differences in growth rates as insignificant. If one country grows at 1 percent while another grows at 3 percent, so what? What difference can 2 percent make?

The answer is: a big difference. Even growth rates that seem small when written in percentage terms seem large after they are compounded for many years. Compounding refers to the accumulation of a growth

rate over a period of time.

Consider an example. Suppose that two college gradu- ates—Jerry and Elaine—both take their first jobs at the age of 22 earning $30,000 a year. Jerry lives in an economy where all incomes grow at 1 percent per year, while Elaine lives in one where incomes grow at 3 percent per year. Straightforward calculations show what happens. Forty years later, when both are 62 years old, Jerry earns $45,000 a year, while Elaine earns $98,000. Because of that difference of 2 percentage points in the growth rate, Elaine’s salary is more than twice Jerry’s.

An old rule of thumb, called the rule of 70, is helpful in understanding growth rates and the effects of compounding. According to the rule of 70, if some variable grows at a rate of x percent per year, then that variable doubles in approximately 70/x years. In Jerry’s economy, incomes grow at 1 percent per year, so it takes about 70 years for incomes to double. In Elaine’s economy, incomes grow at 3 percent per year, so it takes about 70/3, or 23, years for incomes to double.

The rule of 70 applies not only to a growing economy but also to a growing savings account. Here is an example: In 1791, Ben Franklin died and left $5,000 to be invested for a period of 200 years to benefit medical students and scientific research. If this money had earned 7 percent per year (which would, in fact, have been very possible to do), the investment would have doubled in value every 10 years. Over 200 years, it would have doubled 20 times. At the end of 200 years of compounding, the investment would have been worth 220 $5,000, which is about $5 billion. (In fact, Franklin’s $5,000 grew to only $2 million over 200 years because some of the money was spent along the way.)

As these examples show, growth rates compounded over many years can lead to some spectacular results. That is probably why Albert Einstein once called compounding “the greatest mathematical discovery of all time.”

relative to others. One country that has fallen behind is the United Kingdom. In 1870, the United Kingdom was the richest country in the world, with average income about 20 percent higher than that of the United States and about twice that of Canada. Today, average income in the United Kingdom is below average income in its two former colonies.

These data show that the world’s richest countries have no guarantee they will stay the richest and that the world’s poorest countries are not doomed forever to remain in poverty. But what explains these changes over time? Why do some countries zoom ahead while others lag behind? These are precisely the questions that we take up next.

QUICK QUIZ: What is the approximate growth rate of real GDP per person in the United States? Name a country that has had faster growth and a country that has had slower growth.

PRODUCTIVITY : ITS ROLE AND DETERMINANTS

Explaining the large variation in living standards around the world is, in one sense, very easy. As we will see, the explanation can be summarized in a single word—productivity. But, in another sense, the international variation is deeply

CHAPTER 24 PRODUCTION AND GROWTH |

533 |

puzzling. To explain why incomes are so much higher in some countries than in others, we must look at the many factors that determine a nation’s productivity.

WHY PRODUCTIVITY IS SO IMPORTANT

Let’s begin our study of productivity and economic growth by developing a simple model based loosely on Daniel DeFoe’s famous novel Robinson Crusoe. Robinson Crusoe, as you may recall, is a sailor stranded on a desert island. Because Crusoe lives alone, he catches his own fish, grows his own vegetables, and makes his own clothes. We can think of Crusoe’s activities—his production and consumption of fish, vegetables, and clothing—as being a simple economy. By examining Crusoe’s economy, we can learn some lessons that also apply to more complex and realistic economies.

What determines Crusoe’s standard of living? The answer is obvious. If Crusoe is good at catching fish, growing vegetables, and making clothes, he lives well. If he is bad at doing these things, he lives poorly. Because Crusoe gets to consume only what he produces, his living standard is tied to his productive ability.

The term productivity refers to the quantity of goods and services that a worker can produce for each hour of work. In the case of Crusoe’s economy, it is easy to see that productivity is the key determinant of living standards and that growth in productivity is the key determinant of growth in living standards. The more fish Crusoe can catch per hour, the more he eats at dinner. If Crusoe finds a better place to catch fish, his productivity rises. This increase in productivity makes Crusoe better off: He could eat the extra fish, or he could spend less time fishing and devote more time to making other goods he enjoys.

The key role of productivity in determining living standards is as true for nations as it is for stranded sailors. Recall that an economy’s gross domestic product (GDP) measures two things at once: the total income earned by everyone in the economy and the total expenditure on the economy’s output of goods and services. The reason why GDP can measure these two things simultaneously is that, for the economy as a whole, they must be equal. Put simply, an economy’s income is the economy’s output.

Like Crusoe, a nation can enjoy a high standard of living only if it can produce a large quantity of goods and services. Americans live better than Nigerians because American workers are more productive than Nigerian workers. The Japanese have enjoyed more rapid growth in living standards than Argentineans because Japanese workers have experienced more rapidly growing productivity. Indeed, one of the Ten Principles of Economics in Chapter 1 is that a country’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services.

Hence, to understand the large differences in living standards we observe across countries or over time, we must focus on the production of goods and services. But seeing the link between living standards and productivity is only the first step. It leads naturally to the next question: Why are some economies so much better at producing goods and services than others?

pr oductivity

the amount of goods and services produced from each hour of a worker’s time

HOW PRODUCTIVITY IS DETERMINED

Although productivity is uniquely important in determining Robinson Crusoe’s standard of living, many factors determine Crusoe’s productivity. Crusoe will be