504 |

PART EIGHT THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS |

The most obvious feature of these data is that real GDP grows over time. The real GDP of the U.S. economy in 1999 was more than twice its 1970 level. Put differently, the output of goods and services produced in the United States has grown on average about 3 percent per year since 1970. This continued growth in real GDP enables the typical American to enjoy greater economic prosperity than his or her parents and grandparents did.

A second feature of the GDP data is that growth is not steady. The upward climb of real GDP is occasionally interrupted by periods during which GDP declines, called recessions. Figure 22-2 marks recessions with shaded vertical bars. (There is no ironclad rule for when the official business cycle dating committee will declare that a recession has occurred, but a good rule of thumb is two consecutive quarters of falling real GDP.) Recessions are associated not only with lower incomes but also with other forms of economic distress: rising unemployment, falling profits, increased bankruptcies, and so on.

Much of macroeconomics is aimed at explaining the long-run growth and short-run fluctuations in real GDP. As we will see in the coming chapters, we need different models for these two purposes. Because the short-run fluctuations represent deviations from the long-run trend, we first examine the behavior of the economy in the long run. In particular, Chapters 24 through 30 examine how key macroeconomic variables, including real GDP, are determined in the long run. We then build on this analysis to explain short-run fluctuations in Chapters 31 through 33.

QUICK QUIZ: Define real and nominal GDP. Which is a better measure of economic well-being? Why?

GDP AND ECONOMIC WELL-BEING

Earlier in this chapter, GDP was called the best single measure of the economic wellbeing of a society. Now that we know what GDP is, we can evaluate this claim.

As we have seen, GDP measures both the economy’s total income and the economy’s total expenditure on goods and services. Thus, GDP per person tells us the income and expenditure of the average person in the economy. Because most people would prefer to receive higher income and enjoy higher expenditure, GDP per person seems a natural measure of the economic well-being of the average individual.

Yet some people dispute the validity of GDP as a measure of well-being. When Senator Robert Kennedy was running for president in 1968, he gave a moving critique of such economic measures:

[Gross domestic product] does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our courage, nor our wisdom, nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile, and it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

CHAPTER 22 MEASURING A NATION’S INCOME |

505 |

|

|

|

|

IN THE NEWS

GDP Lightens Up

he says, weighs less than a 10-story building erected in the late 19th century.

dently only modestly higher than it was 50 or 100 years ago,” Mr. Greenspan told an audience in Dallas recently.

When you think about it, it’s not so surprising that the economy is getting lighter. An ever-growing proportion of the U.S. GDP consists of things that don’t weigh anything at all—lawyers’ services, psychotherapy, e-mail, online information.

But Mr. Greenspan has a way of making the obvious sound profound. Only “a small fraction” of the nation’s economic growth in the past several decades “represents growth in the tonnage of physical materials—oil, coal, ores, wood, raw chemicals,” he has observed. “The remainder represents new insights into how to rearrange those physical materials to better serve human needs.” . . .

The incredible shrinking GDP helps explain why American workers can produce more for each hour of work than

before. . . . [It] also helps explain there is so much international trade days. “The . . . downsizing of outMr. Greenspan said recently, that products were easier and less costly to move, and most

specially across national borders.” . . .

“The world of 1948 was vastly difMr. Greenspan observed a few s back. “The quintessential model of

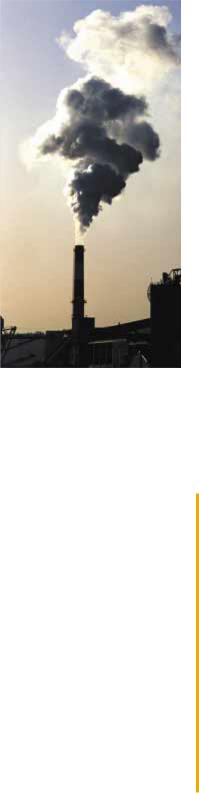

industry might in those days was the array of vast, smoke-encased integrated steel mills . . . on the shores of Lake Michigan. Output was things, big physical things.”

Today, one exemplar of U.S. economic might is Microsoft Corp., with its almost weightless output. “Virtually unimaginable a half-century ago was the extent to which concepts and ideas would substitute for physical resources and human brawn in the production of goods and services,” he has said.

Of course, one thing Made in the U.S. is heavier than it used to be: people. The National Institutes of Health says 22.3% of Americans are obese, up from 12.8% in the early 1960. But Mr. Greenspan doesn’t talk about that.

SOURCE: The Wall Street Journal, May 20, 1999, p. B1.

Much of what Robert Kennedy said is correct. Why then do we care about GDP? The answer is that a large GDP does in fact help us to lead a good life. GDP does not measure the health of our children, but nations with larger GDP can afford better health care for their children. GDP does not measure the quality of their education, but nations with larger GDP can afford better educational systems. GDP does not measure the beauty of our poetry, but nations with larger GDP can afford to teach more of their citizens to read and to enjoy poetry. GDP does not take account of our intelligence, integrity, courage, wisdom, or devotion to country, but all of these laudable attributes are easier to foster when people are less concerned about being able to afford the material necessities of life. In short, GDP does not directly measure those things that make life worthwhile, but it does measure

our ability to obtain the inputs into a worthwhile life.

CHAPTER 22 MEASURING A NATION’S INCOME |

507 |

|

REAL GDP PER |

LIFE |

ADULT |

COUNTRY |

PERSON, 1997 |

EXPECTANCY |

LITERACY |

|

|

|

|

United States |

$29,010 |

77 years |

99% |

Japan |

24,070 |

80 |

99 |

Germany |

21,260 |

77 |

99 |

Mexico |

8,370 |

72 |

90 |

Brazil |

6,480 |

67 |

84 |

Russia |

4,370 |

67 |

99 |

Indonesia |

3,490 |

65 |

85 |

China |

3,130 |

70 |

83 |

India |

1,670 |

63 |

53 |

Pakistan |

1,560 |

64 |

41 |

Bangladesh |

1,050 |

58 |

39 |

Nigeria |

920 |

50 |

59 |

|

|

|

|

Table 22-3

GDP, LIFE EXPECTANCY, AND

LITERACY. The table shows GDP per person and two measures of the quality of life for 12 major countries.

Source: Human Development Report 1999, United Nations.

ment red tape, and the simple desire to sock away some extra cash have driven much of Russia’s economic activity underground.

For the last six years, the Russian economy has been going down, down, down. But as President Boris N. Yeltsin tries to deliver the growth he has promised, economists are taking a closer look at the murky but vibrant shadow economy. It includes everything from small businesses that never report their sales to huge companies that understate their production to avoid taxes.

experts insist that if the economy is taken into account, economy is finally starting to Mr. Yeltsin’s critics comnew calculations are more

than economics. . . .

no question that measuring activity in a former Communist the road to capitalism is a

elusive task.

“There is a serious problem with post-socialist statistics,” said Yegor T. Gaidar, the former Prime Minister and pro-reform director of the Institute of Economic Problems of the Transitional Period.

“Seven years ago to report an increase in the amount of production was to become a Hero of Socialist Labor,” he said. “Now it is to get additional visits from the tax collector.”

SOURCE: The New York Times, May 18, 1997, Week in Review, p. 4.

508 |

PART EIGHT THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS |

maternal mortality, higher rates of child malnutrition, and less common access to safe drinking water. In countries with low GDP per person, fewer school-age children are actually in school, and those who are in school must learn with fewer teachers per student. These countries also tend to have fewer televisions, fewer telephones, fewer paved roads, and fewer households with electricity. International data leave no doubt that a nation’s GDP is closely associated with its citizens’ standard of living.

QUICK QUIZ: Why should policymakers care about GDP?

CONCLUSION

This chapter has discussed how economists measure the total income of a nation. Measurement is, of course, only a starting point. Much of macroeconomics is aimed at revealing the long-run and short-run determinants of a nation’s gross domestic product. Why, for example, is GDP higher in the United States and Japan than in India and Nigeria? What can the governments of the poorest countries do to promote more rapid growth in GDP? Why does GDP in the United States rise rapidly in some years and fall in others? What can U.S. policymakers do to reduce the severity of these fluctuations in GDP? These are the questions we will take up shortly.

At this point, it is important to acknowledge the importance of just measuring GDP. We all get some sense of how the economy is doing as we go about our lives. But the economists who study changes in the economy and the policymakers who formulate economic policies need more than this vague sense—they need concrete data on which to base their judgments. Quantifying the behavior of the economy with statistics such as GDP is, therefore, the first step to developing a science of macroeconomics.

Summar y

Because every transaction has a buyer and a seller, the total expenditure in the economy must equal the total income in the economy.

Gross domestic product (GDP) measures an economy’s total expenditure on newly produced goods and services and the total income earned from the production of these goods and services. More precisely, GDP is the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time.

GDP is divided among four components of expenditure: consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports. Consumption includes spending on goods and services by households, with the exception of

purchases of new housing. Investment includes spending on new equipment and structures, including households’ purchases of new housing. Government purchases include spending on goods and services by local, state, and federal governments. Net exports equal the value of goods and services produced domestically and sold abroad (exports) minus the value of goods and services produced abroad and sold domestically (imports).

Nominal GDP uses current prices to value the economy’s production of goods and services. Real GDP uses constant base-year prices to value the economy’s production of goods and services. The GDP deflator—

CHAPTER 22 MEASURING A NATION’S INCOME |

509 |

calculated from the ratio of nominal to real GDP— measures the level of prices in the economy.

GDP is a good measure of economic well-being because people prefer higher to lower incomes. But it is not a

perfect measure of well-being. For example, GDP excludes the value of leisure and the value of a clean environment.

Key Concepts

microeconomics, p. 494 |

investment, p. 499 |

real GDP, p. 502 |

macroeconomics, p. 494 |

government purchases, p. 499 |

GDP deflator, p. 503 |

gross domestic product (GDP), p. 496 |

net exports, p. 499 |

|

|

consumption, p. 499 |

nominal GDP, p. 502 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Questions for Review |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.Explain why an economy’s income must equal its expenditure.

2.Which contributes more to GDP—the production of an economy car or the production of a luxury car? Why?

3.A farmer sells wheat to a baker for $2. The baker uses the wheat to make bread, which is sold for $3. What is the total contribution of these transactions to GDP?

4.Many years ago Peggy paid $500 to put together a record collection. Today she sold her albums at a garage sale for $100. How does this sale affect current GDP?

5.List the four components of GDP. Give an example of each.

6.Why do economists use real GDP rather than nominal GDP to gauge economic well-being?

7.In the year 2001, the economy produces 100 loaves of bread that sell for $2 each. In the year 2002, the economy produces 200 loaves of bread that sell for $3 each. Calculate nominal GDP, real GDP, and the GDP deflator for each year. (Use 2001 as the base year.) By what percentage does each of these three statistics rise from one year to the next?

8.Why is it desirable for a country to have a large GDP? Give an example of something that would raise GDP and yet be undesirable.

Problems and Applications

1.What components of GDP (if any) would each of the following transactions affect? Explain.

a.A family buys a new refrigerator.

b.Aunt Jane buys a new house.

c.Ford sells a Thunderbird from its inventory.

d.You buy a pizza.

e.California repaves Highway 101.

f.Your parents buy a bottle of French wine.

g.Honda expands its factory in Marysville, Ohio.

think of a reason why households’ purchases of new cars should also be included in investment rather than in consumption? To what other consumption goods might this logic apply?

4.As the chapter states, GDP does not include the value of used goods that are resold. Why would including such transactions make GDP a less informative measure of economic well-being?

5.Below are some data from the land of milk and honey.

2. |

The “government purchases” component of GDP does |

|

|

|

|

|

|

not include spending on transfer payments such as |

|

PRICE |

QUANTITY |

PRICE OF |

QUANTITY |

|

Social Security. Thinking about the definition of GDP, |

|

|

YEAR |

OF MILK |

OF MILK |

HONEY |

OF HONEY |

|

explain why transfer payments are excluded. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. |

Why do you think households’ purchases of new |

2001 |

$1 |

100 qts. |

$2 |

50 qts. |

|

housing are included in the investment component of |

2002 |

$1 |

200 |

$2 |

100 |

|

GDP rather than the consumption component? Can you |

2003 |

$2 |

200 |

$4 |

100 |

512 |

PART EIGHT THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS |

In the preceding chapter we looked at how economists use gross domestic product (GDP) to measure the quantity of goods and services that the economy is producing. This chapter examines how economists measure the overall cost of living. To compare Babe Ruth’s salary of $80,000 to salaries from today, we need to find some way of turning dollar figures into meaningful measures of purchasing power. That is exactly the job of a statistic called the consumer price index. After seeing how the consumer price index is constructed, we discuss how we can use such a price index to compare dollar figures from different points in time.

The consumer price index is used to monitor changes in the cost of living over time. When the consumer price index rises, the typical family has to spend more dollars to maintain the same standard of living. Economists use the term inflation to describe a situation in which the economy’s overall price level is rising. The inflation rate is the percentage change in the price level from the previous period. As we will see in the coming chapters, inflation is a closely watched aspect of macroeconomic performance and is a key variable guiding macroeconomic policy. This chapter provides the background for that analysis by showing how economists measure the inflation rate using the consumer price index.

|

THE CONSUMER PRICE INDEX |

|

|

consumer price |

The consumer price index (CPI) is a measure of the overall cost of the goods and |

index (CPI) |

services bought by a typical consumer. Each month the Bureau of Labor Statistics, |

a measure of the overall cost of |

which is part of the Department of Labor, computes and reports the consumer |

the goods and services bought |

price index. In this section we discuss how the consumer price index is calculated |

by a typical consumer |

and what problems arise in its measurement. We also consider how this index |

|

compares to the GDP deflator, another measure of the overall level of prices, which |

|

we examined in the preceding chapter. |

HOW THE CONSUMER PRICE INDEX IS CALCULATED

When the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates the consumer price index and the inflation rate, it uses data on the prices of thousands of goods and services. To see exactly how these statistics are constructed, let’s consider a simple economy in which consumers buy only two goods—hot dogs and hamburgers. Table 23-1 shows the five steps that the Bureau of Labor Statistics follows.

1. Fix the Basket. The first step in computing the consumer price index is to determine which prices are most important to the typical consumer. If the typical consumer buys more hot dogs than hamburgers, then the price of hot dogs is more important than the price of hamburgers and, therefore, should be given greater weight in measuring the cost of living. The Bureau of Labor Statistics sets these weights by surveying consumers and finding the basket of goods and services that the typical consumer buys. In the example in the table, the typical consumer buys a basket of 4 hot dogs and 2 hamburgers.