- •In praise of the fourth edition

- •CONTENTS

- •FOREWORD

- •The concept of consulting

- •Purpose of the book

- •Terminology

- •Plan of the book

- •ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- •1.1 What is consulting?

- •Box 1.1 On giving and receiving advice

- •1.2 Why are consultants used? Five generic purposes

- •Figure 1.1 Generic consulting purposes

- •Box 1.2 Define the purpose, not the problem

- •1.3 How are consultants used? Ten principal ways

- •Box 1.3 Should consultants justify management decisions?

- •1.4 The consulting process

- •Figure 1.2 Phases of the consulting process

- •1.5 Evolving concepts and scope of management consulting

- •2 THE CONSULTING INDUSTRY

- •2.1 A historical perspective

- •2.2 The current consulting scene

- •2.3 Range of services provided

- •2.4 Generalist and specialist services

- •2.5 Main types of consulting organization

- •2.6 Internal consultants

- •2.7 Management consulting and other professions

- •Figure 2.1 Professional service infrastructure

- •2.8 Management consulting, training and research

- •Box 2.1 Factors differentiating research and consulting

- •3.1 Defining expectations and roles

- •Box 3.1 What it feels like to be a buyer

- •3.2 The client and the consultant systems

- •Box 3.2 Various categories of clients within a client system

- •Box 3.3 Attributes of trusted advisers

- •3.4 Behavioural roles of the consultant

- •Box 3.4 Why process consultation must be a part of every consultation

- •3.5 Further refinement of the role concept

- •3.6 Methods of influencing the client system

- •3.7 Counselling and coaching as tools of consulting

- •Box 3.5 The ICF on coaching and consulting

- •4 CONSULTING AND CHANGE

- •4.1 Understanding the nature of change

- •Figure 4.1 Time span and level of difficulty involved for various levels of change

- •Box 4.1 Which change comes first?

- •Box 4.2 Reasons for resistance to change

- •4.2 How organizations approach change

- •Box 4.3 What is addressed in planning change?

- •Box 4.4 Ten overlapping management styles, from no participation to complete participation

- •4.3 Gaining support for change

- •4.4 Managing conflict

- •Box 4.5 How to manage conflict

- •4.5 Structural arrangements and interventions for assisting change

- •5 CONSULTING AND CULTURE

- •5.1 Understanding and respecting culture

- •Box 5.1 What do we mean by culture?

- •5.2 Levels of culture

- •Box 5.2 Cultural factors affecting management

- •Box 5.3 Japanese culture and management consulting

- •Box 5.4 Cultural values and norms in organizations

- •5.3 Facing culture in consulting assignments

- •Box 5.5 Characteristics of “high-tech” company cultures

- •6.1 Is management consulting a profession?

- •6.2 The professional approach

- •Box 6.1 The power of the professional adviser

- •Box 6.2 Is there conflict of interest? Test your value system.

- •Box 6.3 On audit and consulting

- •6.3 Professional associations and codes of conduct

- •6.4 Certification and licensing

- •Box 6.4 International model for consultant certification (CMC)

- •6.5 Legal liability and professional responsibility

- •7 ENTRY

- •7.1 Initial contacts

- •Box 7.1 What a buyer looks for

- •7.2 Preliminary problem diagnosis

- •Figure 7.1 The consultant’s approach to a management survey

- •Box 7.2 Information materials for preliminary surveys

- •7.3 Terms of reference

- •Box 7.3 Terms of reference – checklist

- •7.4 Assignment strategy and plan

- •Box 7.4 Concepts and terms used in international technical cooperation projects

- •7.5 Proposal to the client

- •7.6 The consulting contract

- •Box 7.5 Confidential information on the client organization

- •Box 7.6 What to cover in a contract – checklist

- •8 DIAGNOSIS

- •8.1 Conceptual framework of diagnosis

- •8.2 Diagnosing purposes and problems

- •Box 8.1 The focus purpose – an example

- •Box 8.2 Issues in problem identification

- •8.3 Defining necessary facts

- •8.4 Sources and ways of obtaining facts

- •Box 8.3 Principles of effective interviewing

- •8.5 Data analysis

- •Box 8.4 Cultural factors in data-gathering – some examples

- •Box 8.5 Difficulties and pitfalls of causal analysis

- •Figure 8.1 Force-field analysis

- •Figure 8.2 Various bases for comparison

- •8.6 Feedback to the client

- •9 ACTION PLANNING

- •9.1 Searching for possible solutions

- •Box 9.1 Checklist of preliminary considerations

- •Box 9.2 Variables for developing new forms of transport

- •9.2 Developing and evaluating alternatives

- •Box 9.3 Searching for an ideal solution – three checklists

- •9.3 Presenting action proposals to the client

- •10 IMPLEMENTATION

- •10.1 The consultant’s role in implementation

- •10.2 Planning and monitoring implementation

- •10.3 Training and developing client staff

- •10.4 Some tactical guidelines for introducing changes in work methods

- •Figure 10.1 Comparison of the effects on eventual performance when using individualized versus conformed initial approaches

- •Figure 10.2 Comparison of spaced practice with a continuous or massed practice approach in terms of performance

- •Figure 10.3 Generalized illustration of the high points in attention level of a captive audience

- •10.5 Maintenance and control of the new practice

- •11.1 Time for withdrawal

- •11.2 Evaluation

- •11.3 Follow-up

- •11.4 Final reporting

- •12.1 Nature and scope of consulting in corporate strategy and general management

- •12.2 Corporate strategy

- •12.3 Processes, systems and structures

- •12.4 Corporate culture and management style

- •12.5 Corporate governance

- •13.1 The developing role of information technology

- •13.2 Scope and special features of IT consulting

- •13.3 An overall model of information systems consulting

- •Figure 13.1 A model of IT consulting

- •Figure 13.2 An IT systems portfolio

- •13.4 Quality of information systems

- •13.5 The providers of IT consulting services

- •Box 13.1 Choosing an IT consultant

- •13.6 Managing an IT consulting project

- •13.7 IT consulting to small businesses

- •13.8 Future perspectives

- •14.1 Creating value

- •14.2 The basic tools

- •14.3 Working capital and liquidity management

- •14.4 Capital structure and the financial markets

- •14.5 Mergers and acquisitions

- •14.6 Finance and operations: capital investment analysis

- •14.7 Accounting systems and budgetary control

- •14.8 Financial management under inflation

- •15.1 The marketing strategy level

- •15.2 Marketing operations

- •15.3 Consulting in commercial enterprises

- •15.4 International marketing

- •15.5 Physical distribution

- •15.6 Public relations

- •16 CONSULTING IN E-BUSINESS

- •16.1 The scope of e-business consulting

- •Figure 16.1 Classification of the connected relationship

- •Box 16.1 British Telecom entering new markets

- •Box 16.2 Pricing models

- •Box 16.3 EasyRentaCar.com breaks the industry rules

- •Box 16.4 The ThomasCook.com story

- •16.4 Dot.com organizations

- •16.5 Internet research

- •17.1 Developing an operations strategy

- •Box 17.1 Performance criteria of operations

- •Box 17.2 Major types of manufacturing choice

- •17.2 The product perspective

- •Box 17.3 Central themes in ineffective and effective development projects

- •17.3 The process perspective

- •17.4 The human aspects of operations

- •18.1 The changing nature of the personnel function

- •18.2 Policies, practices and the human resource audit

- •Box 18.1 The human resource audit (data for the past 12 months)

- •18.3 Human resource planning

- •18.4 Recruitment and selection

- •18.5 Motivation and remuneration

- •18.6 Human resource development

- •18.7 Labour–management relations

- •18.8 New areas and issues

- •Box 18.2 Current issues in Japanese human resource management

- •Box 18.3 Current issues in European HR management

- •19.1 Managing in the knowledge economy

- •Figure 19.1 Knowledge: a key resource of the post-industrial area

- •19.2 Knowledge-based value creation

- •Figure 19.2 The competence ladder

- •Figure 19.3 Four modes of knowledge transformation

- •Figure 19.4 Components of intellectual capital

- •Figure 19.5 What is your strategy to manage knowledge?

- •19.3 Developing a knowledge organization

- •Figure 19.6 Implementation paths for knowledge management

- •Box 19.1 The Siemens Business Services knowledge management framework

- •20.1 Shifts in productivity concepts, factors and conditions

- •Figure 20.1 An integrated model of productivity factors

- •Figure 20.2 A results-oriented human resource development cycle

- •20.2 Productivity and performance measurement

- •Figure 20.3 The contribution of productivity to profits

- •20.3 Approaches and strategies to improve productivity

- •Figure 20.4 Kaizen building-blocks

- •Box 20.1 Green productivity practices

- •Figure 20.5 Nokia’s corporate fitness rating

- •Box 20.2 Benchmarking process

- •20.4 Designing and implementing productivity and performance improvement programmes

- •Figure 20.6 The performance improvement planning process

- •Figure 20.7 The “royal road” of productivity improvement

- •20.5 Tools and techniques for productivity improvement

- •Box 20.3 Some simple productivity tools

- •Box 20.4 Multipurpose productivity techniques

- •Box 20.5 Tools used by most successful companies

- •21.1 Understanding TQM

- •21.2 Cost of quality – quality is free

- •Figure 21.1 Typical quality cost reduction

- •Box 21.1 Cost items of non-conformance associated with internal and external failures

- •Box 21.2 The cost items of conformance

- •21.3 Principles and building-blocks of TQM

- •Figure 21.2 TQM business structures

- •21.4 Implementing TQM

- •Box 21.3 The road to TQM

- •Figure 21.3 TQM process blocks

- •21.5 Principal TQM tools

- •Box 21.4 Tools for simple tasks in quality improvement

- •Figure 21.4 Quality tools according to quality improvement steps

- •Box 21.5 Powerful tools for company-wide TQM

- •21.6 ISO 9000 as a vehicle to TQM

- •21.7 Pitfalls and problems of TQM

- •21.8 Impact on management

- •21.9 Consulting competencies for TQM

- •22.1 What is organizational transformation?

- •22.2 Preparing for transformation

- •Figure 22.1 The change-resistant organization

- •22.3 Strategies and processes of transformation

- •Figure 22.2 Linkage between transformation types and organizational conditions

- •Figure 22.3 Relationships between business performance and types of transformation

- •Box 22.1 Eight stages for transforming an organization

- •22.4 Company turnarounds

- •Box 22.2 Implementing a turnaround plan

- •22.5 Downsizing

- •22.6 Business process re-engineering (BPR)

- •22.7 Outsourcing and insourcing

- •22.8 Joint ventures for transformation

- •22.9 Mergers and acquisitions

- •Box 22.3 Restructuring through acquisitions: the case of Cisco Systems

- •22.10 Networking arrangements

- •22.11 Transforming organizational structures

- •22.12 Ownership restructuring

- •22.13 Privatization

- •22.14 Pitfalls and errors to avoid in transformation

- •23.1 The social dimension of business

- •23.2 Current concepts and trends

- •Box 23.1 International guidelines on socially responsible business

- •23.3 Consulting services

- •Box 23.2 Typology of corporate citizenship consulting

- •23.4 A strategic approach to corporate responsibility

- •Figure 23.1 The total responsibility management system

- •23.5 Consulting in specific functions and areas of business

- •23.6 Future perspectives

- •24.1 Characteristics of small enterprises

- •24.2 The role and profile of the consultant

- •24.4 Areas of special concern

- •24.5 An enabling environment

- •24.6 Innovations in small-business consulting

- •25.1 What is different about micro-enterprises?

- •Box 25.1 Consulting in the informal sector – a mini case study

- •25.3 The special skills of micro-enterprise consultants

- •Box 25.2 Private consulting services for micro-enterprises

- •26.1 The evolving role of government

- •Box 26.1 Reinventing government

- •26.2 Understanding the public sector environment

- •Figure 26.1 The public sector decision-making process

- •Box 26.2 The consultant–client relationship in support of decision-making

- •Box 26.3 “Shoulds” and “should nots” in consulting to government

- •26.3 Working with public sector clients throughout the consulting cycle

- •26.4 The service providers

- •26.5 Some current challenges

- •27.1 The management challenge of the professions

- •27.2 Managing a professional service

- •Box 27.1 Challenges in people management

- •27.3 Managing a professional business

- •Box 27.2 Leverage and profitability

- •Box 27.3 Hunters and farmers

- •27.4 Achieving excellence professionally and in business

- •28.1 The strategic approach

- •28.2 The scope of client services

- •Box 28.1 Could consultants live without fads?

- •28.3 The client base

- •28.4 Growth and expansion

- •28.5 Going international

- •28.6 Profile and image of the firm

- •Box 28.2 Five prototypes of consulting firms

- •28.7 Strategic management in practice

- •Box 28.3 Strategic audit of a consulting firm: checklist of questions

- •Box 28.4 What do we want to know about competitors?

- •Box 28.5 Environmental factors affecting strategy

- •29.1 The marketing approach in consulting

- •Box 29.1 Marketing of consulting: seven fundamental principles

- •29.2 A client’s perspective

- •29.3 Techniques for marketing the consulting firm

- •Box 29.2 Criteria for selecting consultants

- •Box 29.3 Branding – the new myth of marketing?

- •29.4 Techniques for marketing consulting assignments

- •29.5 Marketing to existing clients

- •Box 29.4 The cost of marketing efforts: an example

- •29.6 Managing the marketing process

- •Box 29.5 Information about clients

- •30 COSTS AND FEES

- •30.1 Income-generating activities

- •Table 30.1 Chargeable time

- •30.2 Costing chargeable services

- •30.3 Marketing-policy considerations

- •30.4 Principal fee-setting methods

- •30.5 Fair play in fee-setting and billing

- •30.6 Towards value billing

- •30.7 Costing and pricing an assignment

- •30.8 Billing clients and collecting fees

- •Box 30.1 Information to be provided in a bill

- •31 ASSIGNMENT MANAGEMENT

- •31.1 Structuring and scheduling an assignment

- •31.2 Preparing for an assignment

- •Box 31.1 Checklist of points for briefing

- •31.3 Managing assignment execution

- •31.4 Controlling costs and budgets

- •31.5 Assignment records and reports

- •Figure 31.1 Notification of assignment

- •Box 31.2 Assignment reference report – a checklist

- •31.6 Closing an assignment

- •32.1 What is quality management in consulting?

- •Box 32.1 Primary stakeholders’ needs

- •Box 32.2 Responsibility for quality

- •32.2 Key elements of a quality assurance programme

- •Box 32.3 Introducing a quality assurance programme

- •Box 32.4 Assuring quality during assignments

- •32.3 Quality certification

- •32.4 Sustaining quality

- •33.1 Operating workplan and budget

- •Box 33.1 Ways of improving efficiency and raising profits

- •Table 33.2 Typical structure of expenses and income

- •33.2 Performance monitoring

- •Box 33.2 Monthly controls: a checklist

- •Figure 33.1 Expanded profit model for consulting firms

- •33.3 Bookkeeping and accounting

- •34.1 Drivers for knowledge management in consulting

- •34.2 Factors inherent in the consulting process

- •34.3 A knowledge management programme

- •34.4 Sharing knowledge with clients

- •Box 34.1 Checklist for applying knowledge management in a small or medium-sized consulting firm

- •35.1 Legal forms of business

- •35.2 Management and operations structure

- •Figure 35.1 Possible organizational structure of a consulting company

- •Figure 35.2 Professional core of a consulting unit

- •35.3 IT support and outsourcing

- •35.4 Office facilities

- •36.1 Personal characteristics of consultants

- •36.2 Recruitment and selection

- •Box 36.1 Qualities of a consultant

- •36.3 Career development

- •Box 36.2 Career structure in a consulting firm

- •36.4 Compensation policies and practices

- •Box 36.3 Criteria for partners’ compensation

- •Box 36.4 Ideas for improving compensation policies

- •37.1 What should consultants learn?

- •Box 37.1 Areas of consultant knowledge and skills

- •37.2 Training of new consultants

- •Figure 37.1 Consultant development matrix

- •37.3 Training methods

- •Box 37.2 Training in process consulting

- •37.4 Further training and development of consultants

- •37.5 Motivation for consultant development

- •37.6 Learning options available to sole practitioners

- •38 PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE

- •38.1 Your market

- •Box 38.1 Change in the consulting business

- •38.2 Your profession

- •38.3 Your self-development

- •38.4 Conclusion

- •APPENDICES

- •4 TERMS OF A CONSULTING CONTRACT

- •5 CONSULTING AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

- •7 WRITING REPORTS

- •SUBJECT INDEX

Management consulting

●Can a change in the design eliminate one or more processes? (For example, a process of stamping a metal production may eliminate one or more processes of assembly, though it could also alter the appearance of the product.)

●Can some component parts be standardized? Can variety still be obtained in the product line by using different combinations of components?

The consultant knows that products have to be matched with the equipment on which they are manufactured (e.g. with its dimensions, precision, productivity and cost), and vice versa. In a number of cases, he or she may have to examine this relationship and make recommendations to the client concerning either the product or the equipment used, or both. As mentioned earlier, any proposed modifications in product design should be checked with the marketing specialists for their market penetration potential.

Organization of the product development process

It is not unusual for reorganization of the product development process to reduce development time and costs by two-thirds compared with traditional systems.8 Consultants should look into the following:

●cross-functional problem-solving (including at least marketing, R&D, manufacturing, purchasing, logistics, financial control);

●early detection and solution of development problems (frontloading);

●development team structure;

●project management techniques.

Optimization of these elements should ensure that products are designed for marketing and manufacturing concurrently with the engineering process, entailing a substantial reduction in costs and time to market. Rapid prototyping and other advanced simulation techniques can also substantially reduce time and cost of development.

17.3 The process perspective

The basic units of value creation are business processes, which can be defined as a sequence of activities that takes one or more inputs and creates an output that is of value to the customer. In operations, order fulfilment, which has a client order as input and delivered goods as output, is perhaps the most important value-generating process.

Most major consultancy firms offer their own business process or performance improvement (BPI) programmes, which are usually part of an overall change management methodology. Apart from a change management methodology, process improvement involves looking into specific technical areas and applying the relevant industrial engineering techniques. In general, consultants will have to consider the following areas:

370

Consulting in operations management

–demand forecasting and production planning;

–supply chain and materials management;

–inventory management and utilization of materials;

–flow of work and layout, and logistics;

–setting and improving performance standards (at workplace level);

–maintenance;

–cleaner production and energy saving;

–quality management.

These areas are reviewed briefly below, with the exception of quality management, which is the subject of Chapter 21.

Demand forecasting and production planning

A major challenge of demand forecasting and production planning is the integration of planning approaches and systems across networks of legally independent firms. The enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems used for transaction handling and order execution in most firms nowadays have been supplemented by advanced planning systems for coordinating flows of resources and information, avoiding bottlenecks and meeting due dates. Efficient consumer response and supply management strategies are increasingly integrated into planning systems. The implementation of planning systems has become a major business for operations consultants worldwide.

The choice of the planning method to be used depends on the nature of the operation. In process or line production operations various methods of planning can be applied, ranging from simple and traditional scheduling and charting to the use of sophisticated queuing or waiting-line models. However, special projects, such as the construction of a plant or building of a ship, necessitate the use of network planning methods such as the critical path method (CPM) or the programme evaluation and review technique (PERT), which allow a more rational allocation of resources.

In the case of production that is geared for distribution (as distinct from made- to-order goods or special projects), the starting point for a planning process is the forecast of demand, which is worked out with the marketing specialists. The consultant should check the reliability of such forecasts before going into production planning itself. A discrepancy between sales forecasting and production planning can result in either lost orders or excess inventory, and is often a subject of contention between the marketing and production departments. In addition to the forecast, which is translated into an aggregate of operations for various products in the product mix, the consultant has to calculate the machine hours required for each product component, determine the total working time, and introduce a certain flexibility in the planning system to allow for emergency situations.

One difficulty lies in the fact that there are invariably bottleneck operations, but instead of concentrating on them, many consultants gear their

371

Management consulting

planning and scheduling to all operations. An effective analytical and planning exercise should indicate shortages of machine or operators’ hours in certain work centres and present proposals to management to relieve these difficulties.

Supply chain and materials management

With reduced contribution margins per unit of product sold, increased capital rotation has become an important strategy to maintain the profitability of a company at an acceptable level. Supply chain management, which has become another area of consulting in operations, is the process of developing and managing a firm’s total supply system, including internal and external components. It includes and expands the activities of the purchasing function and the procurement process from a strategic perspective. Materials management concentrates on the coordination and control of the various materials activities. Consulting in supply management may deal with topics such as early involvement of suppliers in product design, supplier selection and qualification methods, the development of vendor building programmes, setting up of crossfunctional teams in procurement, etc.9

In addition to the more strategic orientation of supply chain management there is still much scope for services in the traditional area of materials management.

Inventory management

Consultants need to keep in mind three types of inventory: raw materials, work- in-progress and finished products. One general principle should govern all these: the need to keep them at a minimum but safe level. For raw materials and finished products, a safe level is one that allows for uncertainty of delivery or avoids opportunity costs resulting from lost sales. The notion of such a safety stock, or buffer stock, is not a justification for having a high stock level, nor should it be used indiscriminately to take advantage of quantity discounts or special modes of delivery.

For finished products, the desired level of stock needs to be determined in close consultation with the marketing and finance specialists in an effort to balance opportunity costs against carrying charges (the cost of carrying the inventory).

Great savings in carrying charges can be made if the work-in-progress inventory is kept to a minimum. To achieve this, however, the consultant may have to look at the balance of operations, remove or reduce bottlenecks, and propagate the virtues of a system in which no or very little inventory is allowed to accumulate beside each machine.

In most industries, stock levels have been reduced dramatically in recent years with the implementation of just-in-time (JIT) concepts for all three types of inventory. JIT requires close cooperation between suppliers, the producer

372

Consulting in operations management

and clients, a stable production process, and a “zero defect” quality policy. Conversely, JIT is sometimes difficult to implement for reasons such as the need for more frequent transport from suppliers to producers, congested transport networks, especially in big cities, and the tough requirements on the suppliers.

Most consultants approach the problem of the raw materials inventory by analysing the values of the various items to distinguish the “A” items (which are few in number but very costly) from “B” and “C” items (the latter being the great multitude of relatively cheap items that are carried in stock). An ordering strategy is then developed for the “A” items resting on the use of inventory models to determine the economic order quantity by balancing ordering costs against carrying charges. Quantity discounts can also be evaluated against incremental carrying charges, and a decision can then be reached as to when a quantity discount offer can be attractive. The problem, however, lies in the determination of the buffer stock level. Under normal circumstances, this is calculated by balancing opportunity costs against carrying charges. For the “B” items, ordering is carried out through regular review of stock, or whenever a minimum level is reached. For “C” items, mass orders may be placed at certain points in time.

Utilization of materials

While the focus of attention here is on the raw materials which go towards shaping the final product, the assignment can be extended to cover other materials used in the production process, such as packaging material, fuel, and even paints and lubricants. This is an area where substantial savings can be achieved without too much effort, particularly in certain industries such as manufacture of garments, furniture, metallic products and the like. It stands to reason that the higher the percentage of material cost, the more there is a need for a proper investigation of this area. There are three approaches to reducing waste material:

●changes in design, with a view to reducing waste of raw material;

●if the design cannot be changed, then efforts may be undertaken to improve the yield, by changing the method that is used in cutting garments, metal or wood so as to reduce waste to a minimum, or by changing the original size of the raw material used;

●inevitably some waste will result during the various sequences of production. Two questions should come to mind: can this waste be reworked to yield another by-product or component, or can it be sold?

These questions have gained particular relevance because of a number of environmental regulations forcing producers to recycle materials, operate closed systems or take responsibility for the reuse of wastes. Recycling and waste management have become a special area for consultants.

373

Management consulting

Flow of work and layout

The organization’s production operations normally conform to one of three major types. The first is production by fixed position, in which case the product is stationary and the workers and equipment move, as in building aeroplanes, heavy generators, or ships. Layout can sometimes be improved by shortening the distances travelled by workers, materials and equipment. However, the margin of manoeuvrability is rather limited.

The second is in-line production, where the equipment and machinery are arranged according to the sequence of operations, as in bottling plants, car assembly and food canning operations. In these cases, the layout is more or less dictated by the sequence of operations, which determines how the machinery is placed. Nevertheless, two sorts of issue can be examined by the consultant: the original balance of operations; and the problems that result from the fact that, in many cases, as the enterprise develops and the product line expands, or demand for the product changes, additional lines may be added which often do not work in harmony with the original line. The operations can therefore become unbalanced, with certain stages producing at a faster rate than subsequent or preceding stages. A schematic diagram showing the sequence of operations and the time it takes to perform each one can be quite helpful. Depending on the type of problem faced and the complexity of the situation, correcting for balance can range from simple proposals, e.g. increasing the number of workstations on parts of the line, additional machines or improvement in the method of work, to more sophisticated heuristic approaches.

The third type of organization is that of functional arrangement, where all identical machinery is grouped together and the products move between these machines, depending on the sequence required for each. This is the case in many woodworking workshops and in the textile industry. This type of arrangement allows the consultant to do more to improve productivity through better layout and organization of operations. The key is to identify whether there is one or more finished products that constitute a high percentage of total volume. The machinery needed to produce such items is then detached from a functional layout and arranged along a line layout. The gains in productivity in this case can be substantial.

Logistics

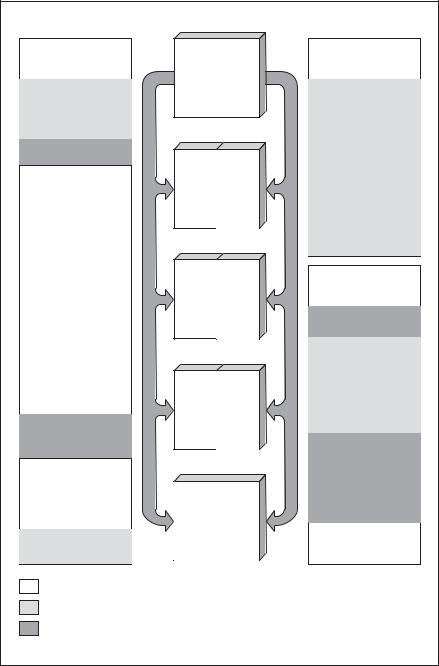

The logistics function in a company can always be described and handled as a flow of information and a flow of goods. As both flows are very complex, the project frame for BPI must be carefully designed. As a checklist we recommend marking on a graph all logistics elements to be covered by the project. The example shown in fig. 17.1 is taken from a company producing and maintaining equipment, which wanted to improve the logistics for spare parts. The defined objectives for this project were: decrease stock by 30 per cent; decrease handling costs; increase delivery performance; and decrease administrative costs.

374

Consulting in operations management

Figure 17.1 Business process improvement in the area of logistics

Planning and |

|

|

|

Warehousing |

control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Customer |

|

|

Sales planning |

|

|

|

Warehouse capacity |

|

|

|

|

planning |

Order handling |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location planning |

Production planning |

|

|

|

Layout planning |

|

|

|

|

|

Requirements plannning |

|

|

Finished |

Equipment planning |

|

Sales |

goods |

||

–gross requirement |

|

|

stocks |

|

–net requirement |

|

|

|

Bin management |

Inventory control |

|

|

|

Warehouse automation |

–raw material |

|

|

|

|

–semi products |

|

|

|

|

–finished goods |

|

Produc- |

Semi |

Material and goods |

–stocktaking |

|

flow |

||

|

|

tion |

product |

|

Material planning |

|

|

stocks |

|

|

|

|

Physical goods flow |

|

–availability control |

|

|

|

|

Informationflow |

|

|

goodsMaterialflowand |

|

–allocation |

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Receiving |

Ordering calculation |

|

|

|

Staging |

–order quantity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–order point |

|

Purchas- |

Raw |

Allocation |

|

|

|

||

|

|

ing |

material |

Packing and dispatch |

Capacity planning |

|

|

stocks |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

–machine |

|

|

|

Expedite |

–personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Purchase handling |

|

|

|

Transport planning |

|

|

|

|

|

–ordering |

|

|

|

Transport routing |

–surveillance |

|

|

|

Optimal distribution |

–receiving |

|

|

|

|

|

Supplier |

|

||

|

|

|

||

Supply market research |

|

|

|

Distribution information |

|

|

|

systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Main area to survey |

|

|

|

|

Secondary area to survey |

|

|

|

|

Not to survey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

375 |

Management consulting

Setting and improving performance standards

This is probably one of the most intricate problems that faces an operations consultant. Performance standards are needed for a variety of reasons, including the determination of labour costs, and hence the ability to decide on matters of pricing and bidding, in “make or buy” decisions, in machine replacement problems, and so on. Such standards are essential for production planning, wages and incentive schemes. Invariably a certain standard exists for every piece of work performed, either a formal recorded standard, or a perceived informal standard which a supervisor or a worker estimates for a given job. The consultant is called upon either to review a formal standard or to establish one. A crucial point is the need to perform the assignment with the knowledge and approval of the persons whose performance is to be assessed, and of the workers’ representatives.

Before setting standards, a consultant working in this field should examine the way a certain operation is being performed and attempt to develop an easier and more effective method. He or she utilizes a number of well-known charts such as the operation chart, the flow chart and activity charts. The consultant should also understand ergonomics and essential elements of job design.

While numerous jobs lend themselves to methods improvement, the consultant should give priority to those that are critical because they either constitute a bottleneck or are repeated by a number of operators. A consultant will find it most useful to invite suggestions from workers, foremen or supervisors, and managers, to involve them in the working out of a new method. In many cases, production workers and technicians will be able to point to improvements that may escape the consultant.

To determine performance standards for the improved systems, generally speaking, one of three methods can be used: works sampling, a stop-watch time study, or predetermined time standards. Alternatively, the consultant may opt for a combination of two or all of these methods at a given working place. For example, work sampling may be used to determine the allowances to be included in a “standard time” based on stop-watch observations.10

Maintenance

The consultant should enquire about the methods used for maintaining and repairing equipment and machinery. In particular, it is appropriate to find out:

●if a preventive maintenance scheme exists, whether it is justified and how it is implemented;

●whether a proper inspection schedule exists;

●if a cost estimate of repairs is made and kept for each machine;

●how normal greasing and lubrication are done and whose responsibility it is to do these jobs.

376

Consulting in operations management

The consultant should also enquire about emergency repairs and consider whether increasing the size of the maintenance crew could reduce the length of time machines are down. In addition, a consultant can examine whether the life of certain individual components of equipment or machines could be prolonged through either redesign or change of lubricant. Finally, machine replacement problems should be studied in relation to maintenance costs.

If major equipment is to be overhauled, especially in process industries, the consultant can help the client to achieve considerable savings by introducing scheduling for such operations (applying network planning techniques if necessary).

Because disruption of production due to machine breakdowns can be very costly, there is a growing trend towards making production staff more maintenance-conscious. Seminars on proper identification of causes of breakdowns, and on the training of both production operators and maintenance crew (which may suggest assigning a certain responsibility to operators for simple oiling and lubrication), could be followed up with performance review seminars at a later stage. Approaches involving all personnel, such as the total productive maintenance (TPM) approach, can pay handsome dividends.

Cleaner production and energy saving

The discussions on sustainable development, along with tighter environmental regulations, have led many companies to review their ways and means of production in light of ecological criteria.11 Consultants may be called in, for example:

●to audit production facilities and propose improvement programmes;

●to assist with environmental impact assessments of major investments;

●to perform life-cycle analyses of products;

●to implement “pollution prevention pays” initiatives, often integrated in total quality management (TQM) or in staff suggestion schemes.

At present, many corporations are implementing the ISO 14000 standard to achieve an integrated environmental management system. In addition, specific technical advice may be sought on topics such as energy saving and recycling.

With the rise in energy costs, there is a need in many client companies to achieve substantial savings in the use of energy. These can result from simple good housekeeping (such as checking that thermostats are functioning and properly set, steam and air leaks repaired, and so on), from minor investments in additional insulation, heat recuperators, power-factor correction and the like, or from major investment decisions about changing to low-waste, lowenergy processes. Many of these issues can be highly technical and require the intervention of specialists. The operations consultant’s contribution lies essentially in examining whether a potential saving in energy costs can be

377