- •In praise of the fourth edition

- •CONTENTS

- •FOREWORD

- •The concept of consulting

- •Purpose of the book

- •Terminology

- •Plan of the book

- •ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- •1.1 What is consulting?

- •Box 1.1 On giving and receiving advice

- •1.2 Why are consultants used? Five generic purposes

- •Figure 1.1 Generic consulting purposes

- •Box 1.2 Define the purpose, not the problem

- •1.3 How are consultants used? Ten principal ways

- •Box 1.3 Should consultants justify management decisions?

- •1.4 The consulting process

- •Figure 1.2 Phases of the consulting process

- •1.5 Evolving concepts and scope of management consulting

- •2 THE CONSULTING INDUSTRY

- •2.1 A historical perspective

- •2.2 The current consulting scene

- •2.3 Range of services provided

- •2.4 Generalist and specialist services

- •2.5 Main types of consulting organization

- •2.6 Internal consultants

- •2.7 Management consulting and other professions

- •Figure 2.1 Professional service infrastructure

- •2.8 Management consulting, training and research

- •Box 2.1 Factors differentiating research and consulting

- •3.1 Defining expectations and roles

- •Box 3.1 What it feels like to be a buyer

- •3.2 The client and the consultant systems

- •Box 3.2 Various categories of clients within a client system

- •Box 3.3 Attributes of trusted advisers

- •3.4 Behavioural roles of the consultant

- •Box 3.4 Why process consultation must be a part of every consultation

- •3.5 Further refinement of the role concept

- •3.6 Methods of influencing the client system

- •3.7 Counselling and coaching as tools of consulting

- •Box 3.5 The ICF on coaching and consulting

- •4 CONSULTING AND CHANGE

- •4.1 Understanding the nature of change

- •Figure 4.1 Time span and level of difficulty involved for various levels of change

- •Box 4.1 Which change comes first?

- •Box 4.2 Reasons for resistance to change

- •4.2 How organizations approach change

- •Box 4.3 What is addressed in planning change?

- •Box 4.4 Ten overlapping management styles, from no participation to complete participation

- •4.3 Gaining support for change

- •4.4 Managing conflict

- •Box 4.5 How to manage conflict

- •4.5 Structural arrangements and interventions for assisting change

- •5 CONSULTING AND CULTURE

- •5.1 Understanding and respecting culture

- •Box 5.1 What do we mean by culture?

- •5.2 Levels of culture

- •Box 5.2 Cultural factors affecting management

- •Box 5.3 Japanese culture and management consulting

- •Box 5.4 Cultural values and norms in organizations

- •5.3 Facing culture in consulting assignments

- •Box 5.5 Characteristics of “high-tech” company cultures

- •6.1 Is management consulting a profession?

- •6.2 The professional approach

- •Box 6.1 The power of the professional adviser

- •Box 6.2 Is there conflict of interest? Test your value system.

- •Box 6.3 On audit and consulting

- •6.3 Professional associations and codes of conduct

- •6.4 Certification and licensing

- •Box 6.4 International model for consultant certification (CMC)

- •6.5 Legal liability and professional responsibility

- •7 ENTRY

- •7.1 Initial contacts

- •Box 7.1 What a buyer looks for

- •7.2 Preliminary problem diagnosis

- •Figure 7.1 The consultant’s approach to a management survey

- •Box 7.2 Information materials for preliminary surveys

- •7.3 Terms of reference

- •Box 7.3 Terms of reference – checklist

- •7.4 Assignment strategy and plan

- •Box 7.4 Concepts and terms used in international technical cooperation projects

- •7.5 Proposal to the client

- •7.6 The consulting contract

- •Box 7.5 Confidential information on the client organization

- •Box 7.6 What to cover in a contract – checklist

- •8 DIAGNOSIS

- •8.1 Conceptual framework of diagnosis

- •8.2 Diagnosing purposes and problems

- •Box 8.1 The focus purpose – an example

- •Box 8.2 Issues in problem identification

- •8.3 Defining necessary facts

- •8.4 Sources and ways of obtaining facts

- •Box 8.3 Principles of effective interviewing

- •8.5 Data analysis

- •Box 8.4 Cultural factors in data-gathering – some examples

- •Box 8.5 Difficulties and pitfalls of causal analysis

- •Figure 8.1 Force-field analysis

- •Figure 8.2 Various bases for comparison

- •8.6 Feedback to the client

- •9 ACTION PLANNING

- •9.1 Searching for possible solutions

- •Box 9.1 Checklist of preliminary considerations

- •Box 9.2 Variables for developing new forms of transport

- •9.2 Developing and evaluating alternatives

- •Box 9.3 Searching for an ideal solution – three checklists

- •9.3 Presenting action proposals to the client

- •10 IMPLEMENTATION

- •10.1 The consultant’s role in implementation

- •10.2 Planning and monitoring implementation

- •10.3 Training and developing client staff

- •10.4 Some tactical guidelines for introducing changes in work methods

- •Figure 10.1 Comparison of the effects on eventual performance when using individualized versus conformed initial approaches

- •Figure 10.2 Comparison of spaced practice with a continuous or massed practice approach in terms of performance

- •Figure 10.3 Generalized illustration of the high points in attention level of a captive audience

- •10.5 Maintenance and control of the new practice

- •11.1 Time for withdrawal

- •11.2 Evaluation

- •11.3 Follow-up

- •11.4 Final reporting

- •12.1 Nature and scope of consulting in corporate strategy and general management

- •12.2 Corporate strategy

- •12.3 Processes, systems and structures

- •12.4 Corporate culture and management style

- •12.5 Corporate governance

- •13.1 The developing role of information technology

- •13.2 Scope and special features of IT consulting

- •13.3 An overall model of information systems consulting

- •Figure 13.1 A model of IT consulting

- •Figure 13.2 An IT systems portfolio

- •13.4 Quality of information systems

- •13.5 The providers of IT consulting services

- •Box 13.1 Choosing an IT consultant

- •13.6 Managing an IT consulting project

- •13.7 IT consulting to small businesses

- •13.8 Future perspectives

- •14.1 Creating value

- •14.2 The basic tools

- •14.3 Working capital and liquidity management

- •14.4 Capital structure and the financial markets

- •14.5 Mergers and acquisitions

- •14.6 Finance and operations: capital investment analysis

- •14.7 Accounting systems and budgetary control

- •14.8 Financial management under inflation

- •15.1 The marketing strategy level

- •15.2 Marketing operations

- •15.3 Consulting in commercial enterprises

- •15.4 International marketing

- •15.5 Physical distribution

- •15.6 Public relations

- •16 CONSULTING IN E-BUSINESS

- •16.1 The scope of e-business consulting

- •Figure 16.1 Classification of the connected relationship

- •Box 16.1 British Telecom entering new markets

- •Box 16.2 Pricing models

- •Box 16.3 EasyRentaCar.com breaks the industry rules

- •Box 16.4 The ThomasCook.com story

- •16.4 Dot.com organizations

- •16.5 Internet research

- •17.1 Developing an operations strategy

- •Box 17.1 Performance criteria of operations

- •Box 17.2 Major types of manufacturing choice

- •17.2 The product perspective

- •Box 17.3 Central themes in ineffective and effective development projects

- •17.3 The process perspective

- •17.4 The human aspects of operations

- •18.1 The changing nature of the personnel function

- •18.2 Policies, practices and the human resource audit

- •Box 18.1 The human resource audit (data for the past 12 months)

- •18.3 Human resource planning

- •18.4 Recruitment and selection

- •18.5 Motivation and remuneration

- •18.6 Human resource development

- •18.7 Labour–management relations

- •18.8 New areas and issues

- •Box 18.2 Current issues in Japanese human resource management

- •Box 18.3 Current issues in European HR management

- •19.1 Managing in the knowledge economy

- •Figure 19.1 Knowledge: a key resource of the post-industrial area

- •19.2 Knowledge-based value creation

- •Figure 19.2 The competence ladder

- •Figure 19.3 Four modes of knowledge transformation

- •Figure 19.4 Components of intellectual capital

- •Figure 19.5 What is your strategy to manage knowledge?

- •19.3 Developing a knowledge organization

- •Figure 19.6 Implementation paths for knowledge management

- •Box 19.1 The Siemens Business Services knowledge management framework

- •20.1 Shifts in productivity concepts, factors and conditions

- •Figure 20.1 An integrated model of productivity factors

- •Figure 20.2 A results-oriented human resource development cycle

- •20.2 Productivity and performance measurement

- •Figure 20.3 The contribution of productivity to profits

- •20.3 Approaches and strategies to improve productivity

- •Figure 20.4 Kaizen building-blocks

- •Box 20.1 Green productivity practices

- •Figure 20.5 Nokia’s corporate fitness rating

- •Box 20.2 Benchmarking process

- •20.4 Designing and implementing productivity and performance improvement programmes

- •Figure 20.6 The performance improvement planning process

- •Figure 20.7 The “royal road” of productivity improvement

- •20.5 Tools and techniques for productivity improvement

- •Box 20.3 Some simple productivity tools

- •Box 20.4 Multipurpose productivity techniques

- •Box 20.5 Tools used by most successful companies

- •21.1 Understanding TQM

- •21.2 Cost of quality – quality is free

- •Figure 21.1 Typical quality cost reduction

- •Box 21.1 Cost items of non-conformance associated with internal and external failures

- •Box 21.2 The cost items of conformance

- •21.3 Principles and building-blocks of TQM

- •Figure 21.2 TQM business structures

- •21.4 Implementing TQM

- •Box 21.3 The road to TQM

- •Figure 21.3 TQM process blocks

- •21.5 Principal TQM tools

- •Box 21.4 Tools for simple tasks in quality improvement

- •Figure 21.4 Quality tools according to quality improvement steps

- •Box 21.5 Powerful tools for company-wide TQM

- •21.6 ISO 9000 as a vehicle to TQM

- •21.7 Pitfalls and problems of TQM

- •21.8 Impact on management

- •21.9 Consulting competencies for TQM

- •22.1 What is organizational transformation?

- •22.2 Preparing for transformation

- •Figure 22.1 The change-resistant organization

- •22.3 Strategies and processes of transformation

- •Figure 22.2 Linkage between transformation types and organizational conditions

- •Figure 22.3 Relationships between business performance and types of transformation

- •Box 22.1 Eight stages for transforming an organization

- •22.4 Company turnarounds

- •Box 22.2 Implementing a turnaround plan

- •22.5 Downsizing

- •22.6 Business process re-engineering (BPR)

- •22.7 Outsourcing and insourcing

- •22.8 Joint ventures for transformation

- •22.9 Mergers and acquisitions

- •Box 22.3 Restructuring through acquisitions: the case of Cisco Systems

- •22.10 Networking arrangements

- •22.11 Transforming organizational structures

- •22.12 Ownership restructuring

- •22.13 Privatization

- •22.14 Pitfalls and errors to avoid in transformation

- •23.1 The social dimension of business

- •23.2 Current concepts and trends

- •Box 23.1 International guidelines on socially responsible business

- •23.3 Consulting services

- •Box 23.2 Typology of corporate citizenship consulting

- •23.4 A strategic approach to corporate responsibility

- •Figure 23.1 The total responsibility management system

- •23.5 Consulting in specific functions and areas of business

- •23.6 Future perspectives

- •24.1 Characteristics of small enterprises

- •24.2 The role and profile of the consultant

- •24.4 Areas of special concern

- •24.5 An enabling environment

- •24.6 Innovations in small-business consulting

- •25.1 What is different about micro-enterprises?

- •Box 25.1 Consulting in the informal sector – a mini case study

- •25.3 The special skills of micro-enterprise consultants

- •Box 25.2 Private consulting services for micro-enterprises

- •26.1 The evolving role of government

- •Box 26.1 Reinventing government

- •26.2 Understanding the public sector environment

- •Figure 26.1 The public sector decision-making process

- •Box 26.2 The consultant–client relationship in support of decision-making

- •Box 26.3 “Shoulds” and “should nots” in consulting to government

- •26.3 Working with public sector clients throughout the consulting cycle

- •26.4 The service providers

- •26.5 Some current challenges

- •27.1 The management challenge of the professions

- •27.2 Managing a professional service

- •Box 27.1 Challenges in people management

- •27.3 Managing a professional business

- •Box 27.2 Leverage and profitability

- •Box 27.3 Hunters and farmers

- •27.4 Achieving excellence professionally and in business

- •28.1 The strategic approach

- •28.2 The scope of client services

- •Box 28.1 Could consultants live without fads?

- •28.3 The client base

- •28.4 Growth and expansion

- •28.5 Going international

- •28.6 Profile and image of the firm

- •Box 28.2 Five prototypes of consulting firms

- •28.7 Strategic management in practice

- •Box 28.3 Strategic audit of a consulting firm: checklist of questions

- •Box 28.4 What do we want to know about competitors?

- •Box 28.5 Environmental factors affecting strategy

- •29.1 The marketing approach in consulting

- •Box 29.1 Marketing of consulting: seven fundamental principles

- •29.2 A client’s perspective

- •29.3 Techniques for marketing the consulting firm

- •Box 29.2 Criteria for selecting consultants

- •Box 29.3 Branding – the new myth of marketing?

- •29.4 Techniques for marketing consulting assignments

- •29.5 Marketing to existing clients

- •Box 29.4 The cost of marketing efforts: an example

- •29.6 Managing the marketing process

- •Box 29.5 Information about clients

- •30 COSTS AND FEES

- •30.1 Income-generating activities

- •Table 30.1 Chargeable time

- •30.2 Costing chargeable services

- •30.3 Marketing-policy considerations

- •30.4 Principal fee-setting methods

- •30.5 Fair play in fee-setting and billing

- •30.6 Towards value billing

- •30.7 Costing and pricing an assignment

- •30.8 Billing clients and collecting fees

- •Box 30.1 Information to be provided in a bill

- •31 ASSIGNMENT MANAGEMENT

- •31.1 Structuring and scheduling an assignment

- •31.2 Preparing for an assignment

- •Box 31.1 Checklist of points for briefing

- •31.3 Managing assignment execution

- •31.4 Controlling costs and budgets

- •31.5 Assignment records and reports

- •Figure 31.1 Notification of assignment

- •Box 31.2 Assignment reference report – a checklist

- •31.6 Closing an assignment

- •32.1 What is quality management in consulting?

- •Box 32.1 Primary stakeholders’ needs

- •Box 32.2 Responsibility for quality

- •32.2 Key elements of a quality assurance programme

- •Box 32.3 Introducing a quality assurance programme

- •Box 32.4 Assuring quality during assignments

- •32.3 Quality certification

- •32.4 Sustaining quality

- •33.1 Operating workplan and budget

- •Box 33.1 Ways of improving efficiency and raising profits

- •Table 33.2 Typical structure of expenses and income

- •33.2 Performance monitoring

- •Box 33.2 Monthly controls: a checklist

- •Figure 33.1 Expanded profit model for consulting firms

- •33.3 Bookkeeping and accounting

- •34.1 Drivers for knowledge management in consulting

- •34.2 Factors inherent in the consulting process

- •34.3 A knowledge management programme

- •34.4 Sharing knowledge with clients

- •Box 34.1 Checklist for applying knowledge management in a small or medium-sized consulting firm

- •35.1 Legal forms of business

- •35.2 Management and operations structure

- •Figure 35.1 Possible organizational structure of a consulting company

- •Figure 35.2 Professional core of a consulting unit

- •35.3 IT support and outsourcing

- •35.4 Office facilities

- •36.1 Personal characteristics of consultants

- •36.2 Recruitment and selection

- •Box 36.1 Qualities of a consultant

- •36.3 Career development

- •Box 36.2 Career structure in a consulting firm

- •36.4 Compensation policies and practices

- •Box 36.3 Criteria for partners’ compensation

- •Box 36.4 Ideas for improving compensation policies

- •37.1 What should consultants learn?

- •Box 37.1 Areas of consultant knowledge and skills

- •37.2 Training of new consultants

- •Figure 37.1 Consultant development matrix

- •37.3 Training methods

- •Box 37.2 Training in process consulting

- •37.4 Further training and development of consultants

- •37.5 Motivation for consultant development

- •37.6 Learning options available to sole practitioners

- •38 PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE

- •38.1 Your market

- •Box 38.1 Change in the consulting business

- •38.2 Your profession

- •38.3 Your self-development

- •38.4 Conclusion

- •APPENDICES

- •4 TERMS OF A CONSULTING CONTRACT

- •5 CONSULTING AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

- •7 WRITING REPORTS

- •SUBJECT INDEX

Consulting on the social role and responsibility of business

Business ethics. Ethics consultants work with companies on a range of initiatives that may be broad or narrow in scope. Large-scale initiatives may create guidelines for ethical decision-making, and operations for line managers from a variety of departments. More specific initiatives can include training and policies around ethical contract negotiations with foreign partners, and harassment and mistreatment of workers. Ethics consultants also reach into a variety of citizenship areas, including the design of codes of conduct and performance systems.

Communication. Many companies do not have enough staff to add citizenshiprelated activities to their agenda. There is a growing need for consultants who can temporarily serve as contract staff to implement citizenship projects. An especially common area is internal and external communications to promote citizenship activities.

Specific consultancies around major operating lines. In many respects, each function of the business possesses its own set of social responsibility issues that may require the support and guidance of consultants. As a matter of principle, every consultant advising on specific functions, systems or aspects of a business needs to be aware of the social dimension involved and to help the client to make socially responsible choices and decisions, or to direct the client to an appropriate specialist competent in such questions (see section 23.5).

23.4 A strategic approach to corporate responsibility

To assist clients to achieve excellence in corporate responsibility, consultants should possess expertise in strategic management and organizational change processes. For an approach to be successful, it must be integrated into the overall business and operational strategy. If corporate citizenship practices are fundamental to all business operations, it is less likely that specific initiatives will be discontinued, or will be removed from the day-to-day concerns of decision-makers and managers. Consultants can serve their clients by helping them formulate and implement a corporate citizenship strategy, develop their codes, strengthen their stakeholder involvement, measure performance, and train/coach their senior executives and middle managers in leadership and management. Clients can then use consultants to provide advice and support on the more specialized and technical aspects of social responsibility, such as environmental remediation, human rights practices, supply chain management or community involvement.

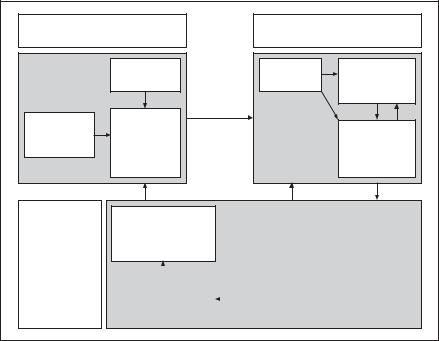

The elements of a strategic management approach to corporate citizenship are captured in a framework developed by Sandra Waddock and Charles Bodwell at the ILO and called “total responsibility management” (TRM):

TRM approaches can potentially provide a means for integrating external demands and pressures for responsible practice, calls for accountability and transparency, the proliferation of codes of conduct, managing supply chains responsibly and sustainably, and stakeholder engagement into a single approach for responsibility practices within the firm.9

537

Management consulting

The TRM approach builds on well-known performance management systems such as total quality management. Figure 23.1 illustrates the three main elements or levels that make up the emerging TRM approach: (1) vision-setting and leadership systems, (2) integration of responsibility into strategies and practices, and (3) assessment, improvement and learning systems. The logic of the system is similar to that of strategic management processes used for any function of the business. The difference is in the details of its implementation. To use a TRM approach, consultants must understand the social context in which their client operates. The discussion below details how consultants can support their clients through each level of the framework, and provides guidance on the particular skills and processes consultants should have ready in their toolkit.

Level 1 – Vision-setting and leadership systems

At this level, consultants typically work with top management to define a strategic agenda for corporate citizenship and to drive a change process from the top down. In particular, consultants should assist their clients in implementing the following steps:

●Defining the integration between traditional business strategy and corporate citizenship. This process should clarify and express a corporate citizenship business model that describes the interdependence between the company’s social role and responsibility and its business success. This definition will, for example, provide the underpinnings to help decisionmakers to understand the elements of the triple bottom line, and how they can reinforce one another. Defining the link between conventional business strategy and the social role of business is essential for ensuring the long-term sustainability of corporate citizenship processes.

●Identifying priorities for corporate citizenship. After defining the integration of business and citizenship strategies, decision-makers need to identify strategic priorities that will drive resource allocation and management systems dedicated to addressing specific issues such as labour practices, supply chain management, environment, community and others. This process may involve selecting one or more of the multilateral codes of conduct (such as those listed in box 23.1) to endorse and implement.

●Leadership roles and commitment to strategic goals. The consultant should work with senior executives to define specific strategic goals, corporate policies and measurable objectives for their corporate citizenship strategy. In practice, these goals should reflect an intersection of business outcomes and social/environmental outcomes. Consultants should then work with senior managers to define their specific roles in driving and communicating the strategy.

●Committing to core citizenship processes. As noted earlier, corporate citizenship management frameworks commonly emphasize stakeholder engagement, transparency, social reporting, and measurement. Many of these tactics are unfamiliar to corporate managers. They represent new ways

538

Consulting on the social role and responsibility of business

Figure 23.1 The total responsibility management system

Vision-setting and leadership systems

|

Foundational |

|

|

values |

|

Stakeholder |

Responsible |

|

vision, |

||

engagement |

||

values and |

||

processes |

||

leadership |

||

|

||

|

commitments |

Integration into strategies and management practices

Strategy |

Human |

|

resource |

|

responsibility |

|

Responsibility |

|

integration |

|

management |

|

systems |

Assessment improvement, and learning systems

Improvement:

remediation, innovation and learning

|

|

|

|

Responsibility measurement system |

Transparency and |

|

|

Results: performance, stakeholder, |

|

accountability for |

|

|

and ecological outcomes and |

|

|

|

|||

results and impacts |

|

|

responsibility |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: S. Waddock, C. Bodwell and S. Graves: “Responsibility: the new business imperative”, in Academy of Management Executive, May 2002 (forthcoming).

of doing business, and may conflict with conventional policies related to secrecy, financial reporting, and tightly controlled communications practices. Consultants should work to underscore that these tactics will be necessary to support strategic goals, and to secure the commitment of senior executives to support and lead the processes.

Succeeding at this first level of an intervention is not easy. It requires the consultant to mix science and art in defining an integrative corporate citizenship strategy that senior executives can comprehend, support and lead. Consultants need to come prepared with a toolkit of knowledge and methods that support strategy formulation.

Identifying key motivating drivers for corporate citizenship. It is vital for consultants to understand the factors that motivate corporate citizenship within a given organization, and to build the consciousness of key managers around these motivating drivers:10

●Values: are based on morals, and a desire to “give back” to society.

●Compliance: government regulations and grassroots activists create pressures for compliance. This leads to corporate policies and strategies that respond to legislation, criticism, inspection, pressure groups, etc.

539

Management consulting

●Intangibles: intangible factors include reputation, brand and relationships. Intangible drivers often lead to responses that attempt to minimize the risks of pressures for compliance and create savings for the business. Proactive corporate citizenship becomes a tool to create trusting relationships with, for example, governments or NGOs, and thus reduce the risk of activism and opposition. Intangible drivers can also lead to responses that support value creation. For example, developing the intangible asset of reputation can support sales and employee recruitment and retention.

●Market: market drivers lead to the inclusion of social, as well as market-based goals in projects and investments, such as product launches, production, purchasing, or employee training. The projects may also be carried out with non-traditional stakeholders. Examples are job training of low-income individuals, clean production technologies, socially responsible consumer products (e.g. clean-burning gas), employee stock ownership plans, etc.

Unfortunately, these motivating drivers often operate independently of one another, and encourage divergent strategies that yield suboptimal outcomes for the business and its stakeholders. For example, values may lead to charity programmes. Compliance drivers may guide the business to do the least possible to comply with laws and regulations. Intangible drivers may lead to strategic philanthropy, cause-marketing, or partnerships with NGOs and government. Finally, market drivers can lead to business initiatives such as redesigning manufacturing to be less wasteful, or developing new markets in low-income areas. Most companies keep these strategies separate, and fail to optimize the resources they invest in corporate citizenship.

Understanding and applying the business case. As discussed earlier, leading models of corporate social responsibility contend that there is no contradiction between social responsibility and profitability. In fact, the argument goes, social responsibility increasingly performs a high-value support role for the bottom line. Research supports the claim that corporate citizenship adds value to traditional business goals, such as consumer attraction and retention, employee recruitment and retention, worker productivity and overall financial performance. In addition, it supports such considerations as innovation, reputation and “licence to operate”.

Consultants must first present the business case and help clients to understand how their own business and particular line functions will benefit from corporate citizenship. Consultants must also be prepared to help clients to build creative strategies that use citizenship approaches to meet societal obligations while generating returns on investments. To succeed, citizenship consultants need a broader perspective than most traditional management consultants.

Organizational diagnosis. There are two dimensions of organizational diagnosis – the marketplace and society. The marketplace is the province of traditional management consultants, but it is essential that corporate citizenship consultants possess an understanding of their client’s business fundamentals. There are two reasons for this. First, consultants need to speak their client’s

540

Consulting on the social role and responsibility of business

language. Managers who are sceptical about corporate citizenship may perceive the consultant as an infiltrator representing forces that are (in the extreme) conspiring to shut down operations. Second, consultants need to be able to translate and integrate. Managers often have difficulty in conceptually linking their day-to-day responsibilities with the requirements of corporate citizenship. Consultants can provide a valuable service by helping to build this conceptual bridge between the fundamentals of business and citizenship.

The second dimension of organizational diagnosis is an understanding of the relationship between the business and society, which is where the majority of citizenship concerns are played out. Depending on the project, the consultant may need technical expertise, such as in environmental analysis. However, the consultant should also possess broader, strategic knowledge, including how to diagnose current practice and performance around key dimensions of citizenship. Where is the company’s performance effective and where is it inadequate? Consultants will do well to use frameworks such as the Global Compact or the OECD Guidelines, which can help them to make judgements and to legitimize conclusions.

Stakeholder identification. The dynamics of corporate citizenship operations manifest themselves through the interplay between a company and its stakeholders. The level of stakeholder satisfaction represents the principal form of feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of corporate management. It is therefore essential for corporations to identify and engage with key stakeholders. However, transnational organizations face a vast array of stakeholders. The challenge for consultants and their clients is to identify the key stakeholder groups – and their representatives – that should be part of the corporate responsibility strategy. One pitfall to avoid is assigning the main role to stakeholders who appear to be most threatening and behave most aggressively. Consultants should possess expertise in stakeholder analysis, mapping and relationship-building.

Issues identification and environmental scanning. The social, cultural, institutional, legal, supervisory and political environment for corporate citizenship is crucial. Consultants need to help their clients assess how current corporate operations intersect with the environment to create either vulnerabilities or opportunities for the client’s relationship and behaviour towards key stakeholders. Strategic information is needed that helps a company to craft policies and programmatic responses. The issues identification and scanning process should also help a company select its top strategic priorities. A company in a service industry, for example, may have few if any direct concerns regarding supply chain management and sourcing. However, it may have significant concerns regarding the quality of education systems as it struggles to find, recruit and retain adequately skilled employees.

Strategy formulation. The consultant should work with the client to take the outcomes of the above processes and formulate a strategic plan that is focused and clear. The plan should help managers demarcate a path between goals and concrete projects, owners, roles, measures and timelines. In

541

Management consulting

citizenship consulting, a strategic plan serves as the client’s touchstone. It not only specifies purpose and activities it helps managers answer fundamental questions regarding the relevance of corporate citizenship, its purpose, and fit within the organization.

Level 2 – Integration of responsibility into strategy and practices

At this level, consultants can work with both senior executives and mid-level line managers. It is at this point that the company begins to implement its strategy – designing processes, systems, practices and programmes based on the new goals and priorities. Consultants may assist their clients in the following steps:

●Creating management performance systems. To implement a corporate citizenship strategy successfully, goals and action plans have to be transformed into an operational agenda and reflected in performance contracts of business lines, departments and managers.

●Redesigning practices and creating programmes. The company will need to design new practices and systems to support the goals of corporate citizenship. If, for instance, a goal is to avoid suppliers that violate the human rights of their employees, then the company will need to create specific policies, strategies, management systems, monitoring mechanisms and reporting systems. Alternatively, if the company’s goal is to reduce greenhouse emissions, it will need to modify its production model. Redesigning corporate practices and policies will typically require specialized expertise.

●Process implementation. At this level, the company will form and implement systems to engage stakeholders, monitor issues, and develop mechanisms to increase transparency. These processes should not be formed and managed in isolation, but integrated across business lines, and used as tools both to implement strategy and to create feedback mechanisms to reformulate the strategy.

At this level of intervention, the consultants’ toolkit needs to expand to include content expertise for specific issues as well as knowledge of organizational behaviour, change and strategy. Toolkit elements include the following:

Organizational change. Consultants will often find that there is much within the client organization that resists the implementation of corporate citizenship strategy, structures and programmes. Resistance (see also Chapter 4) may be intentional or unintentional. In either case, the challenge it presents to consulting initiatives is formidable. Consultants need to possess skills in change management and strategic planning. It is advisable for consultants to work only with organizations in which senior executives have demonstrated their commitment, and it is often useful to solidify this commitment by making the point of contact a senior-level manager. When this is not possible, it is

542

Consulting on the social role and responsibility of business

important to use formal engagements to involve senior executives throughout the process. If the initiative is being driven from the bottom (or middle) upwards, rather than top-down, it is important for the consultant to assess realistically what can be achieved. A consultant can provide a valuable service by coaching middle managers on leadership and change initiatives, and by guiding the client through the change process. Consultants are also advised to insist on a participatory methodology that involves a variety of managers from important departments. They should work with key client contacts to develop a map of key stakeholders within the organization who should play an active and engaged role in the project.

Management support and coaching. A significant barrier to the change process is lack of expertise, experience and knowledge among managers on the social role and responsibility of the business. Consultants can design and implement training programmes that are tied into corporate strategy, and that support the management of corporate citizenship initiatives.

Technical and policy expertise. Given the complex organizational dynamics of corporate citizenship, it is easy to overlook that consulting initiatives require at least a modest level of technical and content-specific knowledge. Corporate citizenship engages the business in an array of policy issues and concerns that it has probably previously ignored. Clients will look to consultants to provide guidance and knowledge in these areas. The challenge for consultants is to help the business understand how it can engage in social issues effectively, while preserving its core business mission and functions.

Level 3 – Assessment, improvement and learning systems

At this level, consultants will work with both senior executives and line managers, and provide the company and its stakeholders with feedback about performance, direction for improvement, and the information needed to revise and improve the corporate citizenship strategy.

Measurement systems. These include systems that measure the impact of the strategy for the business and its stakeholders, as well as systems to determine whether the operations are managed effectively and efficiently. Measurement of corporate citizenship is at an early stage of evolution. At this level, consultants will need to bring expertise, knowledge and creativity to the process of creating measurement systems.

Reporting, monitoring and verification systems. Related to measurement, these systems function as the principal vehicle for increasing corporate transparency and accountability to stakeholders. These systems are also at an early stage of development. Consultants will need expertise in designing effective reporting, monitoring and verification systems.

Improvement and innovation. By tracking and measuring impacts and performance, consultants can work with clients to learn from measurement and reporting systems, and help define plans to improve performance, drive innovative practices, and enhance the existing strategy.

543