Словари и журналы / Психологические журналы / p1Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology

.pdf

1

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (2002), 75, 1–13

© 2002 The British Psychological Society

www.bps.org.uk

Designated redundant but escaping lay-off: A special group of lay-off survivors

Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen*

Management and Labour Studies, Faculty of Business Administration,

University of Windsor, Canada

A 3-year longitudinal panel study compared employees who had been declared redundant (N=49) in the initial downsizing stage, but who remained in the organization, and employees who had not been designated redundant (N=118). During the downsizing period, those who were declared redundant reported a signiŽ cant decline in organizational trust and commitment compared with those who were not designated redundant. However, in the post-downsizing period those who had been designated redundant reported a signiŽ cant increase in their job satisfaction, trust in the organization and organizational commitment, reporting higher levels on these factors than survivors who had not been designated redundant. There were no signiŽ cant differences between the two groups for self-reported job performance, perceived job security and perceived organizational morale but there were signiŽ - cant time effects. Perceived job security showed a dramatic increase at Time 3 following the involuntary departure phase of the downsizing and continued to increase signiŽcantly, so that perceived job security in the post-downsizing period

was signiŽ cantly higher than during any of the three |

downsizing phases. Survivors |

reported a signiŽ cant decline in job performance |

in the early phases of the |

downsizing and in the post-downsizing period 3 years later job performance remained slightly below the initial level. Although there was a signiŽcant increase in perceived organizational morale in the post-downsizing period, the level of perceived morale continued to be below the mid-point of the scale. The level of organizational trust showed a similar trend indicating that downsizing has a long-term negative effect on these two variables.

Acommon practice in organizations undergoing downsizing is to designate certain job positions as redundant. Frequently, it is left up to the individuals whose jobs have been declared redundant either to find another position within the organization within a specified time period or be laid off. The majority of these individuals do eventually end up as lay-off victims. There has been a great deal of research, beginning with the Depression up through the 1990s, on redundant employees who have lost their jobs (e.g. Cobb & Kasl, 1977; DeFrank & Ivancevich, 1986; Fryer & Payne, 1986; Hanisch, 1999; Hartley & Fryer, 1987; Leana & Feldman, 1994; Payne & Hartley, 1987; Swinburne, 1981). However, some employees who have been declared redundant end

*Requests for reprints should be addressed to Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen, Management and Labour Studies, Faculty of Business Administration, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, Ontario N9B 3P4, Canada (e-mail: mas@uwindsor.ca).

2 Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen

up remaining with the organization. It is these employees who are the focus of the present study.

The purpose of this study was to compare employees who had been declared redundant with those who had not over a 3-year period beginning with the initial phase of the downsizing, through the midand late-downsizing phase, to the postdownsizing period. Kozlowski, Chao, Smith, and Hedlund (1993) suggested that survivors’ reactions to organizational downsizing are probably influenced by the extent to which the downsizing directly affects them. These researchers speculated that those survivors who are personally affected by the downsizing will have stronger reactions than those survivors who are not directly involved. The major premise of the present study was that those employees who are declared at risk of losing their jobs are more directly affected by the downsizing than employees who have not been designated redundant. Therefore, the redundant group should respond more negatively to the downsizing even though they have managed to retain their jobs in the end. Only one study has empirically examined this issue and its findings provide some support for this premise. Armstrong-Stassen (1997) found that managers in a major United States telecommunications corporation who had been designated redundant during downsizing but who remained with the corporation reported more job-related tension and burnout, perceived less organizational support, and were less likely to engage in proactive types of coping than managers who had not been designated redundant.

The present study examined three job-related factors (job satisfaction, job performance, and perceived job security) and three organization-related factors (organizational morale, organizational trust, and organizational commitment) that have been identified in the survivor literature as particularly susceptible to be negatively affected by downsizing. Researchers have found organizational downsizing to be associated with a significant decline in job satisfaction (Armstrong-Stassen, Cameron, & Horsburgh, 1996; Luthans & Sommer, 1999), reduced job performance (Armstrong-Stassen, 1998; Jalajas & Bommer, 1996), increased job insecurity (Cameron, Freeman, & Mishra, 1993), a deterioration in organizational morale (Cameron et al., 1993; Jalajas & Bommer, 1996; Worrall, Cooper, & Campbell-Jamieson, 2000), decreased trust in the organization (Kets de Vries & Balazs, 1997), and reduced commitment to the organization (Kets de Vries & Balazs, 1997; Luthans & Sommer, 1999). It was therefore predicted that there would be a decline in these joband organization-related factors during the downsizing period and that this decline would be even greater for those employees who had been designated redundant. At the present time, empirical evidence of the long-term effects of organizational downsizing on survivors’ attitudes and behaviour is limited because most of the studies on survivors have been crosssectional, conducted shortly after the downsizing took place. Only a few longitudinal studies exist that have included the post-downsizing period. Therefore, one of the objectives of the present study was to determine whether or not the expected differences between those designated redundant and those not would continue to be present a year following the completion of the downsizing.

Method

Research site

The participating organization, a department of the Canadian federal government, began a mandated large-scale reduction (over 20%) of its workforce in 1996. The Time 1 (T1) data were collected in early 1996 following a programme review to identify those programmes that would

Designated redundant |

3 |

either be reduced or totally eliminated. Based upon the results of the programme review, some employees were designated redundant, i..e they were targeted for possible lay-off. The Time 2 (T2) data were collected 6 months later in the autumn of 1996 during which time employees who had been designated redundant were offered early departure and early retirement packages. The Time 3 (T3) data collection was conducted in the autumn of 1997. Between the T2 and T3 data collections, the department implemented involuntary departures, i.e. lay-offs. The Time 4 (T4) data were collected in early 1999 after completion of the downsizing.

Participants and procedures

Questionnaire survey packets were mailed to randomly selected employees. The 167 respondents who completed all four questionnaires included 68 men and 99 women. Their average age was 42 years (SD=6.55) and they had worked for the department an average of 16 years (SD=6.55). They were primarily officer analysts (41%), middle managers (21%) and supervisors (16%). Atotal of 49 (20%) had been declared redundant in 1996. The questionnaires were coded so each respondent’s questionnaires could be matched up across the data collection periods. The overall response rate at T1 was 53%. Fifty-three per cent of those who completed a questionnaire at T1 participated at T2, 66%of those who participated at T2 also completed a questionnaire at T3, and 63%of those who participated at T3 completed a questionnaire at T4.

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, all measures consisted of a 5-point Likert response format. The reliability coefficients for each of the measures are shown in Table 1.

Job-related factors

The 9-item measure of job facet satisfaction included 5 items from the Job Diagnostic Survey (Hackman & Oldham, 1974) and 4 items developed for this study. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of satisfaction with various aspects of their job including the amount of job security, challenge, and the resources and training available to help them do their job. The response categories ranged from Extremely Satisfied to Extremely Dissatisfied. The self-rated performance scale was developed for this study. Respondents were asked to rate their performance, compared to their average performance prior to the downsizing, on 11 different aspects including quality of work, productivity, assuming responsibility, and amount of effort expended on the job. The response categories were Well Above Average, Somewhat Above Average, About Average, Slightly Below Average, and Considerably Below Average. Perceived job security was assessed with 3 items adapted from Jick’s (1979) job security index. The items reflect how much confidence respondents have that their job will continue (ranging from 100%confidence to 0% confidence), their degree of worry about their job security (ranging from Not At All Worried to Extremely Worried), and their perceived likelihood of being laid off (ranging from Not At All Likely to Extremely Likely).

Organization-related factors

Perceived organizational morale was assessed with a 7-item semantic differential scale adapted from Scott (1967). Respondents were asked to describe how employees felt in general at the present time. Sample bipolar adjectives are enthusiastic/indifferent and encouraged/ discouraged. Perceived organizational trust was measured with 3 items including the 2-item trust scale developed by Ashford, Lee, and Bobko (1989) and 1 item from the trust scale of Cook and Wall (1980). A sample item is ‘I trust this organization to look out for my best interests.’ The response categories ranged from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. Organizational commitment was assessed with 3 items from the Affective Commitment Scale (Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993). A sample item is ‘[department] has a great deal of personal meaning for me’. Response categories ranged from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree.

Redundant status

Respondents were asked to indicate if they had personally been designated an ‘affected’ employee (this is the term the department used to reflect redundancy). The response categories were Yes or No.

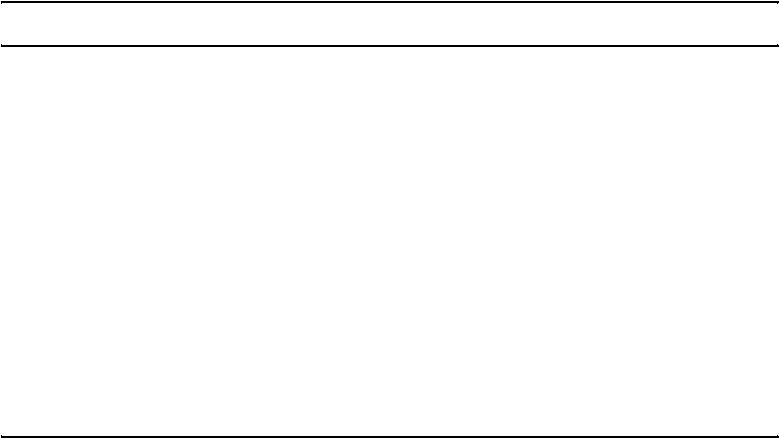

Table 1. Overall averaged item means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations

M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(SD) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

1. |

Redundant statusa |

— |

2.08 |

|

|

|

2. |

T1 |

Job satisfaction |

3.23 |

.79 |

|

|

|

|

|

(.66) |

2.13 |

|

|

3. |

T1 |

Job performance |

3.54 |

.27 |

.91 |

|

|

|

|

(.74) |

2.02 |

|

|

4. |

T1 |

Job security |

2.97 |

.59 |

.24 |

|

|

|

|

(.98) |

2.09 |

|

|

5. |

T1 |

Morale |

2.40 |

.56 |

.22 |

|

|

|

|

(.69) |

2.01 |

|

|

6. |

T1 |

Trust |

2.44 |

.62 |

.22 |

|

|

|

|

(.88) |

2.04 |

|

|

7. |

T1 |

Commitment |

2.97 |

.53 |

.22 |

|

|

|

|

(.92) |

2.11 |

|

|

8. |

T2 |

Job satisfaction |

3.16 |

.69 |

.23 |

|

|

|

|

(.66) |

2.09 |

|

|

9. |

T2 |

Job performance |

3.32 |

.18 |

.54 |

|

|

|

|

(.69) |

2.09 |

|

|

10. |

T2 |

Job security |

2.95 |

.39 |

.15 |

|

|

|

|

(1.01) |

2.01 |

|

|

11. |

T2 |

Morale |

2.30 |

.36 |

.06 |

|

|

|

|

(.71) |

2.02 |

|

|

12. |

T2 |

Trust |

2.45 |

.54 |

.17 |

|

|

|

|

(.89) |

2.12 |

|

|

13. |

T2 |

Commitment |

2.90 |

.42 |

.19 |

|

|

|

|

(.92) |

|

|

|

.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.53 |

.84 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.41 |

.53 |

.84 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.26 |

.40 |

.58 |

.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

.49 |

.46 |

.52 |

.37 |

.83 |

|

|

|

|

.18 |

.19 |

.15 |

.04 |

.27 |

.89 |

|

|

|

.75 |

.38 |

.35 |

.15 |

.53 |

.18 |

.81 |

|

|

.27 |

.54 |

.41 |

.17 |

.49 |

.13 |

.37 |

.90 |

|

.41 |

.56 |

.75 |

.48 |

.59 |

.17 |

.44 |

.50 |

.88 |

.19 |

.40 |

.45 |

.72 |

.46 |

.14 |

.17 |

.32 |

.59 .78 |

Stassen-Armstrong Marjorie 4

Table 1. Continued

M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(SD) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

14. |

T3 |

Job satisfaction |

3.26 |

2.12 |

.50 |

.18 |

.42 |

.35 |

.35 |

.25 |

.52 |

.27 |

.43 |

.30 |

.45 |

.33 |

.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.72) |

2.07 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15. |

T3 |

Job performance |

3.39 |

.18 |

.46 |

.13 |

.12 |

.17 |

.11 |

.20 |

.57 |

.13 |

.09 |

.20 |

.16 |

.36 |

.89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.67) |

2.11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16. |

T3 |

Job security |

3.41 |

.39 |

.20 |

.65 |

.34 |

.29 |

.21 |

.36 |

.10 |

.65 |

.13 |

.31 |

.16 |

.61 |

.18 |

.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.97) |

2.09 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17. |

T3 |

Morale |

2.42 |

.30 |

.03 |

.27 |

.48 |

.33 |

.21 |

.28 |

.15 |

.24 |

.43 |

.36 |

.25 |

.57 |

.17 |

.34 |

.91 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.76) |

2.15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18. |

T3 |

Trust |

2.42 |

.51 |

.17 |

.40 |

.48 |

.66 |

.40 |

.52 |

.16 |

.40 |

.41 |

.69 |

.45 |

.62 |

.24 |

.47 |

.52 |

.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.87) |

2.10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19. |

T3 |

Commitment |

2.89 |

.39 |

.18 |

.29 |

.36 |

.47 |

.61 |

.34 |

.09 |

.23 |

.21 |

.48 |

.60 |

.52 |

.30 |

.29 |

.35 |

.59 |

.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1.00) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20. |

T4 |

Job satisfaction |

3.41 |

.05 |

.57 |

.15 |

.39 |

.35 |

.46 |

.35 |

.52 |

.19 |

.33 |

.31 |

.53 |

.32 |

.63 |

.30 |

.41 |

.42 |

.49 |

.40 |

.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.67) |

2.08 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21. |

T4 |

Job performance |

3.50 |

.30 |

.50 |

.26 |

.09 |

.16 |

.24 |

.25 |

.49 |

.20 |

.01 |

.17 |

.26 |

.28 |

.65 |

.21 |

.08 |

.19 |

.21 |

.32 |

.90 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.69) |

2.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22. |

T4 |

Job security |

3.77 |

.31 |

.21 |

.58 |

.25 |

.23 |

.18 |

.30 |

.12 |

.50 |

.08 |

.24 |

.08 |

.44 |

.15 |

.75 |

.25 |

.27 |

.18 |

.45 |

.27 |

.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.95) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23. |

T4 |

Morale |

2.59 |

.05 |

.34 |

.12 |

.29 |

.34 |

.29 |

.22 |

.31 |

.09 |

.20 |

.34 |

.40 |

.28 |

.42 |

.22 |

.27 |

.43 |

.40 |

.34 |

.62 |

.18 |

.34 |

.91 |

|

|

|

|

(.77) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24. |

T4 |

Trust |

2.61 |

.04 |

.43 |

.09 |

.31 |

.31 |

.55 |

.37 |

.41 |

.12 |

.33 |

.34 |

.58 |

.35 |

.49 |

.18 |

.36 |

.37 |

.63 |

.43 |

.64 |

.24 |

.34 |

.62 |

.88 |

|

|

|

(.88) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25. |

T4 |

Commitment |

2.96 |

.05 |

.30 |

.08 |

.15 |

.20 |

.35 |

.59 |

.23 |

.04 |

.11 |

.18 |

.37 |

.56 |

.37 |

.15 |

.18 |

.24 |

.39 |

.68 |

.47 |

.18 |

.19 |

.46 |

.59 .81 |

|

|

|

(.98) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aRedundant status was scored 1=Not designated redundant and 2=Designated redundant.

Note. SigniŽ cance levels are: r>15, p<.05; r>20, p<.01; r>26, p<.001. Reliability coefficients (Cronbach alpha coefficients) are shown in bold on the diagonal.

redundant Designated

5

6 Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen

Demographic variables

Respondents were asked to indicate how long they had worked for the department, their job classification, age, sex, marital status, and the highest level of education they had completed.

Data analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance, with redundant status as the between subjects factor and time as the within-subjects factor, along with paired t tests, were used to identify significant differences over time and between those respondents who had been designated redundant and those who had not.

Results

There were no significant differences for being designated redundant for sex (c2=.13, p=.72), job position (c2=.00, p=.97), tenure (t=.94, p=.24), and age (t=.26, p=.80). The zero-order correlations for the major variables for the four periods are given in Table 1. Of the 300 off-diagonal correlations, 27 represent test–retest correlations where a moderate to high correlation is likely. Of the remaining 263 correlations, only 25, or less than 10%, had correlation coefficients greater than .50. Half of these were accounted for by the relationship of job satisfaction with the other variables. Thus, there is only minimal overlapping variance among the variables. What is noteworthy in Table 1 is that the levels of perceived organizational morale and trust in the organization were below the mid-point of the scale for all four time periods.

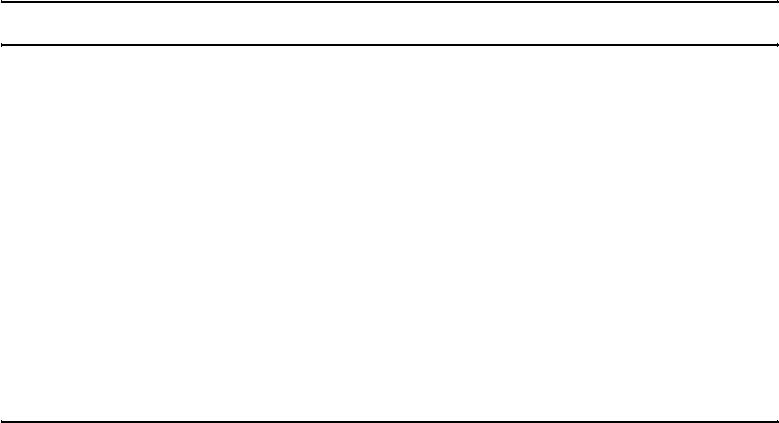

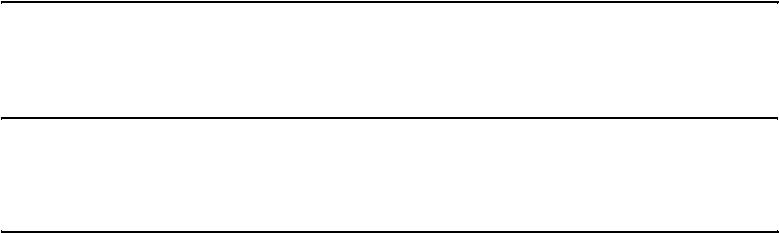

The averaged item means and standard deviations for the two redundant status groups (designated redundant or not) for the job-related factors across the four time periods are shown in Table 2 along with the repeated measures analysis of variance F values. The paired-samples t test results are presented in Table 3. There was a significant redundant status×time effect for job satisfaction. Those designated redundant reported significantly higher job satisfaction at T4 compared with the other three periods. Initially, they reported lower job satisfaction than those not designated redundant, but in the post-downsizing period those declared redundant reported higher job satisfaction than those who had not been designated redundant. There was a significant time effect for job performance and job security. Both groups reported a significant decline in job performance between T1 and T2 and then a significant increase at T4 compared with T2, although the T4 level of job performance for those not designated redundant remained below the T1 level. Both groups reported a significant increase in job security between T1/T2 and T3 and another significant increase between T3 and T4.

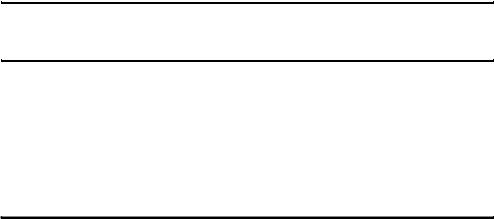

The averaged item means and standard deviations for the organization-related factors are presented in Table 4 along with the repeated measures analysis of variance F values. The paired-samples t test results are shown in Table 5. There was a significant redundant status×time effect for organizational trust and organizational commitment. Survivors who had been designated redundant reported a significant decrease in trust in the department at T3 compared with T2 and then a significant increase between T3 and T4. Survivors who had not been designated redundant reported a slight increase in trust in the department at T3 although this was not statistically significant. At T4, survivors who had been designated redundant reported greater trust in the department than those who had not been designated redundant. For organizational commitment, survivors who had been designated redundant reported a decrease in commitment to the department at T2 and T3 compared with T1 and then a significant increase

Table 2. Averaged item means, standard deviations, and repeated measures ANOVA F values for the job-related factors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Redundant |

|

Time 1 |

Time 2 |

Time 3 |

Time 4 |

|

|

|

|

status |

|

||||

Redundant |

Redundant |

Redundant |

Redundant |

Redundant |

|

|

3 |

|

|||||

status |

status |

status |

status |

status |

|

Time |

|

Time |

|

||||

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

F value |

d.f. |

F value |

d.f. |

F value |

d.f. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job satisfaction |

3.16 |

3.23 |

3.06 |

3.21 |

3.16 |

3.30 |

3.49 |

3.35 |

<1.00 |

1,145 |

9.29*** |

3,143 |

2.82* |

3,143 |

|

(.63) |

(.68) |

(.61) |

(.71) |

(.64) |

(.74) |

(.65) |

(.69) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job performance |

3.47 |

3.60 |

3.23 |

3.37 |

3.33 |

3.42 |

3.45 |

3.49 |

<1.00 |

1,140 |

6.16*** |

3,138 |

<1.00 |

3,138 |

|

(.76) |

(.68) |

(.59) |

(.70) |

(.60) |

(.69) |

(.71) |

(.67) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job security |

2.92 |

2.98 |

2.79 |

3.00 |

3.21 |

3.48 |

3.72 |

3.81 |

<1.00 |

1,163 |

41.59*** |

3,161 |

1.24 |

3,161 |

|

(1.05) |

(.96) |

(1.07) |

(.98) |

(1.09) |

(.92) |

(1.08) |

(.90) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

*p<.05; ***p<.001.

Note. Ns for those designated redundant ranged from 43 for job performance to 47 for job security. For those not designated redundant the Ns ranged from 99 for job performance to 118 for job security.

redundant Designated

7

8 |

Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3. Paired-samples t-test results for the job-related factors |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1 |

T1 |

T1 |

T2 |

T2 |

T3 |

|

|

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

|

|

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T3 |

T4 |

T4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Designated redundant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job satisfaction |

1.51 |

.25 |

23.47*** |

21.04 |

24.88*** |

24.72*** |

|

Job performance |

2.32* |

.55 |

.10 |

21.14 |

22.22* |

21.38 |

|

Job security |

1.31 |

22.11* |

25.56*** |

23.09** |

25.90*** |

24.58*** |

Not designated redundant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job satisfaction |

.94 |

2.92 |

21.91 |

21.31 |

22.80* |

21.03 |

|

Job performance |

3.93*** |

2.58* |

1.44 |

2.47 |

22.62** |

1.36 |

|

Job security |

2.30 |

27.04*** |

210.36*** |

26.54*** |

29.11*** |

25.32*** |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

between T2/T3 and T4. Survivors who had been designated redundant actually reported greater commitment to the department at T4 than those not designated redundant whose commitment remained relatively stable across all four time periods. There was a significant time effect for perceived organizational morale. Both groups reported a significant increase in perceived organizational morale at T4 although the level of perceived morale even at T4 was still well below the mid-point of the scale.

Because of the small number of participants in this study, additional power analyses were conducted. For the redundant status×time effects, the observed power for the three significant interactions was .84 for organizational commitment×time, .79 for organizational trust×time, and .67 for job satisfaction×time. These effect sizes would be within the acceptable limits (Murphy & Myors, 1998). However, the observed power indicators for the three non-significant interactions were less than .50, which is below the acceptable limit (.33 for perceived job security×time, .22 for perceived organizational morale×time, and .10 for job performance ×time). The observed power indicators for the main effects of time were above .90 for all variables except for organizational commitment, which was .64. The observed power for the main effect of redundant status was below the .50 level for all variables.

Discussion

This is one of a very few studies to examine job-and organization-related factors from the initial phases of organizational downsizing through the downsizing phases of voluntary departures and then involuntary departures to the post-downsizing period. Overall, the results indicate that within a year following organizational downsizing the negative effects that occurred during the downsizing began to dissipate. For perceived job security, the negative effect began to fade when employees found that they had survived a period of involuntary departures during the downsizing and, by the postdownsizing period, job security was significantly higher than during any period of the downsizing. The findings suggest that organizational downsizing does not have a long-term effect on survivors. However, this may be an erroneous conclusion especiallyin regard to perceived organizational morale and trust. The overall means for

Table 4. Averaged item means, standard deviations, and repeated ANOVA F values for the organization-related factors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Redundant |

|

Time 1 |

Time 2 |

Time 3 |

Time 4 |

|

|

|

|

status |

|

||||

Redundant |

Redundant |

Redundant |

Redundant |

Redundant |

|

|

3 |

|

|||||

status |

status |

status |

status |

status |

|

Time |

|

Time |

|

||||

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

F value |

d.f. |

F value |

d.f. |

F value |

d.f. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Organizational morale |

2.30 |

2.43 |

2.30 |

2.32 |

2.33 |

2.45 |

2.63 |

2.59 |

<1.00 |

1,155 |

5.48*** |

3,153 |

<1.00 |

3,153 |

|

(.69) |

(.69) |

(.67) |

(.74) |

(.72) |

(.77) |

(.82) |

(.77) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Organizational trust |

2.43 |

2.44 |

2.43 |

2.46 |

2.22 |

2.51 |

2.67 |

2.58 |

<1.00 |

1,164 |

5.77*** |

3,162 |

3.61* |

3,162 |

|

(.89) |

(.88) |

(.87) |

(.90) |

(.87) |

(.87) |

(.89) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Organizational commitment |

2.93 |

2.99 |

2.76 |

2.97 |

2.73 |

2.95 |

3.10 |

2.90 |

<1.00 |

1,160 |

2.65* |

3,158 |

4.11** |

3,158 |

|

(.97) |

(.90) |

(.86) |

(.94) |

(1.01) |

(.98) |

(.90) |

(.98) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Note. Ns for those designated redundant ranged from 46 for organizational morale to 49 for organizational trust. For those not designated redundant the Ns ranged from 111 for organizational morale to 117 for organizational trust.

redundant Designated

9

10 |

Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5. Paired-samples t-test results for the organization-related factors |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1 |

T1 |

T1 |

T2 |

T2 |

T3 |

|

|

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

vs. |

|

|

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T3 |

T4 |

T4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Designated redundant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived organizational morale |

2.04 |

2.12 |

22.71** |

2.25 |

22.66* |

23.18** |

|

Organizational trust |

.00 |

1.81 |

21.83 |

2.03* |

21.99 |

24.03*** |

|

Organizational commitment |

1.63 |

1.58 |

21.06 |

.23 |

22.68** |

23.26** |

Not designated redundant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived organizational morale |

1.86 |

2.43 |

21.80 |

22.05* |

23.33*** |

21.48 |

|

Organizational trust |

2.42 |

21.12 |

21.97 |

2.73 |

21.75 |

21.27 |

|

Organizational commitment |

.38 |

.58 |

1.06 |

.39 |

.85 |

.61 |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

perceived organizational morale and organizational trust were all below the mid-point of the scale across the four periods. Other researchers (Armstrong-Stassen, 1998; Worrall et al., 2000) have found similarly low levels of organizational morale and trust among managers in public sector organizations following organizational restructuring and downsizing. There is some evidence that morale and trust are immediately, and seriously, undermined by organizational downsizing (American Management Association, 1996). In the present study, the employees of this department had advance knowledge of the downsizing (this was announced by the government the previous year) and they also knew that their department was targeted for over a 20%reduction of its workforce. It is possible, and indeed highly likely, that organizational morale and trust began to deteriorate prior to the actual downsizing.

It was predicted that those employees who had been declared redundant would respond more negatively to the downsizing than those employees who were not designated redundant. There were significant differences over time for job satisfaction, organizational trust and organizational commitment. Those declared redundant showed greater change (decreases during the downsizing period and then increases in the post-downsizing period) than those survivors who were not designated redundant. The present study expanded upon the exploratory study reported by ArmstrongStassen (1997). That study was limited by the small sample size (20 managers who were designated redundant and 17 managers who were not) and the fact that the data were only collected 18 to 24 months after the last of a series of downsizings and not during the actual downsizings. Armstrong-Stassen (1997) found that managers who had been declared redundant were significantly less likely to engage in proactive types of coping, more likely to report strain and burnout, and less likely to perceive support from the organization. Except for the significant redundant status×time interactions for job satisfaction, organizational trust and organizational commitment, the present study found no significant differences across any of the four periods between those who had been declared redundant and those who had not. There are two possible explanations for the discrepancy in the findings of these two studies. First, the studies focused upon different variables. It is possible that greater differences will be found for variables associated with stress, coping and strain than for job-and organization-related