- •Introduction

- •Who This Book Is For

- •What This Book Covers

- •How This Book Is Structured

- •What You Need to Use This Book

- •Conventions

- •Source Code

- •Errata

- •p2p.wrox.com

- •What Are Regular Expressions?

- •What Can Regular Expressions Be Used For?

- •Finding Doubled Words

- •Checking Input from Web Forms

- •Changing Date Formats

- •Finding Incorrect Case

- •Adding Links to URLs

- •Regular Expressions You Already Use

- •Search and Replace in Word Processors

- •Directory Listings

- •Online Searching

- •Why Regular Expressions Seem Intimidating

- •Compact, Cryptic Syntax

- •Whitespace Can Significantly Alter the Meaning

- •No Standards Body

- •Differences between Implementations

- •Characters Change Meaning in Different Contexts

- •Regular Expressions Can Be Case Sensitive

- •Case-Sensitive and Case-Insensitive Matching

- •Case and Metacharacters

- •Continual Evolution in Techniques Supported

- •Multiple Solutions for a Single Problem

- •What You Want to Do with a Regular Expression

- •Replacing Text in Quantity

- •Regular Expression Tools

- •findstr

- •Microsoft Word

- •StarOffice Writer/OpenOffice.org Writer

- •Komodo Rx Package

- •PowerGrep

- •Microsoft Excel

- •JavaScript and JScript

- •VBScript

- •Visual Basic.NET

- •Java

- •Perl

- •MySQL

- •SQL Server 2000

- •W3C XML Schema

- •An Analytical Approach to Using Regular Expressions

- •Express and Document What You Want to Do in English

- •Consider the Regular Expression Options Available

- •Consider Sensitivity and Specificity

- •Create Appropriate Regular Expressions

- •Document All but Simple Regular Expressions

- •Document What You Expect the Regular Expression to Do

- •Document What You Want to Match

- •Test the Results of a Regular Expression

- •Matching Single Characters

- •Matching Sequences of Characters That Each Occur Once

- •Introducing Metacharacters

- •Matching Sequences of Different Characters

- •Matching Optional Characters

- •Matching Multiple Optional Characters

- •Other Cardinality Operators

- •The * Quantifier

- •The + Quantifier

- •The Curly-Brace Syntax

- •The {n} Syntax

- •The {n,m} Syntax

- •Exercises

- •Regular Expression Metacharacters

- •Thinking about Characters and Positions

- •The Period (.) Metacharacter

- •Matching Variably Structured Part Numbers

- •Matching a Literal Period

- •The \w Metacharacter

- •The \W Metacharacter

- •Digits and Nondigits

- •The \d Metacharacter

- •Canadian Postal Code Example

- •The \D Metacharacter

- •Alternatives to \d and \D

- •The \s Metacharacter

- •Handling Optional Whitespace

- •The \S Metacharacter

- •The \t Metacharacter

- •The \n Metacharacter

- •Escaped Characters

- •Finding the Backslash

- •Modifiers

- •Global Search

- •Case-Insensitive Search

- •Exercises

- •Introduction to Character Classes

- •Choice between Two Characters

- •Using Quantifiers with Character Classes

- •Using the \b Metacharacter in Character Classes

- •Selecting Literal Square Brackets

- •Using Ranges in Character Classes

- •Alphabetic Ranges

- •Use [A-z] With Care

- •Digit Ranges in Character Classes

- •Hexadecimal Numbers

- •IP Addresses

- •Reverse Ranges in Character Classes

- •A Potential Range Trap

- •Finding HTML Heading Elements

- •Metacharacter Meaning within Character Classes

- •The ^ metacharacter

- •How to Use the - Metacharacter

- •Negated Character Classes

- •Combining Positive and Negative Character Classes

- •POSIX Character Classes

- •The [:alnum:] Character Class

- •Exercises

- •String, Line, and Word Boundaries

- •The ^ Metacharacter

- •The ^ Metacharacter and Multiline Mode

- •The $ Metacharacter

- •The $ Metacharacter in Multiline Mode

- •Using the ^ and $ Metacharacters Together

- •Matching Blank Lines

- •Working with Dollar Amounts

- •Revisiting the IP Address Example

- •What Is a Word?

- •Identifying Word Boundaries

- •The \< Syntax

- •The \>Syntax

- •The \b Syntax

- •The \B Metacharacter

- •Less-Common Word-Boundary Metacharacters

- •Exercises

- •Grouping Using Parentheses

- •Parentheses and Quantifiers

- •Matching Literal Parentheses

- •U.S. Telephone Number Example

- •Alternation

- •Choosing among Multiple Options

- •Unexpected Alternation Behavior

- •Capturing Parentheses

- •Numbering of Captured Groups

- •Numbering When Using Nested Parentheses

- •Named Groups

- •Non-Capturing Parentheses

- •Back References

- •Exercises

- •Why You Need Lookahead and Lookbehind

- •The (? metacharacters

- •Lookahead

- •Positive Lookahead

- •Negative Lookahead

- •Positive Lookahead Examples

- •Positive Lookahead in the Same Document

- •Inserting an Apostrophe

- •Lookbehind

- •Positive Lookbehind

- •Negative Lookbehind

- •How to Match Positions

- •Adding Commas to Large Numbers

- •Exercises

- •What Are Sensitivity and Specificity?

- •Extreme Sensitivity, Awful Specificity

- •Email Addresses Example

- •Replacing Hyphens Example

- •The Sensitivity/Specificity Trade-Off

- •Sensitivity, Specificity, and Positional Characters

- •Sensitivity, Specificity, and Modes

- •Sensitivity, Specificity, and Lookahead and Lookbehind

- •How Much Should the Regular Expressions Do?

- •Abbreviations

- •Characters from Other Languages

- •Names

- •Sensitivity and How to Achieve It

- •Specificity and How to Maximize It

- •Exercises

- •Documenting Regular Expressions

- •Document the Problem Definition

- •Add Comments to Your Code

- •Making Use of Extended Mode

- •Know Your Data

- •Abbreviations

- •Proper Names

- •Incorrect Spelling

- •Creating Test Cases

- •Debugging Regular Expressions

- •Treacherous Whitespace

- •Backslashes Causing Problems

- •Considering Other Causes

- •The User Interface

- •Metacharacters Available

- •Quantifiers

- •The @ Quantifier

- •The {n,m} Syntax

- •Modes

- •Character Classes

- •Back References

- •Lookahead and Lookbehind

- •Lazy Matching versus Greedy Matching

- •Examples

- •Character Class Examples, Including Ranges

- •Whole Word Searches

- •Search-and-Replace Examples

- •Changing Name Structure Using Back References

- •Manipulating Dates

- •The Star Training Company Example

- •Regular Expressions in Visual Basic for Applications

- •Exercises

- •The User Interface

- •Metacharacters Available

- •Quantifiers

- •Modes

- •Character Classes

- •Alternation

- •Back References

- •Lookahead and Lookbehind

- •Search Example

- •Search-and-Replace Example

- •Online Chats

- •POSIX Character Classes

- •Matching Numeric Digits

- •Exercises

- •Introducing findstr

- •Finding Literal Text

- •Quantifiers

- •Character Classes

- •Command-Line Switch Examples

- •The /v Switch

- •The /a Switch

- •Single File Examples

- •Simple Character Class Example

- •Find Protocols Example

- •Multiple File Example

- •A Filelist Example

- •Exercises

- •The PowerGREP Interface

- •A Simple Find Example

- •The Replace Tab

- •The File Finder Tab

- •Syntax Coloring

- •Other Tabs

- •Numeric Digits and Alphabetic Characters

- •Quantifiers

- •Back References

- •Alternation

- •Line Position Metacharacters

- •Word-Boundary Metacharacters

- •Lookahead and Lookbehind

- •Longer Examples

- •Finding HTML Horizontal Rule Elements

- •Matching Time Example

- •Exercises

- •The Excel Find Interface

- •Escaping Wildcard Characters

- •Using Wildcards in Data Forms

- •Using Wildcards in Filters

- •Exercises

- •Using LIKE with Regular Expressions

- •The % Metacharacter

- •The _ Metacharacter

- •Character Classes

- •Negated Character Classes

- •Using Full-Text Search

- •Using The CONTAINS Predicate

- •Document Filters on Image Columns

- •Exercises

- •Using the _ and % Metacharacters

- •Testing Matching of Literals: _ and % Metacharacters

- •Using Positional Metacharacters

- •Using Character Classes

- •Quantifiers

- •Social Security Number Example

- •Exercises

- •The Interface to Metacharacters in Microsoft Access

- •Creating a Hard-Wired Query

- •Creating a Parameter Query

- •Using the ? Metacharacter

- •Using the * Metacharacter

- •Using the # Metacharacter

- •Using the # Character with Date/Time Data

- •Using Character Classes in Access

- •Exercises

- •The RegExp Object

- •Attributes of the RegExp Object

- •The Other Properties of the RegExp Object

- •The test() Method of the RegExp Object

- •The exec() Method of the RegExp Object

- •The String Object

- •Metacharacters in JavaScript and JScript

- •SSN Validation Example

- •Exercises

- •The RegExp Object and How to Use It

- •Quantifiers

- •Positional Metacharacters

- •Character Classes

- •Word Boundaries

- •Lookahead

- •Grouping and Nongrouping Parentheses

- •Exercises

- •The System.Text.RegularExpressions namespace

- •A Simple Visual Basic .NET Example

- •The Classes of System.Text.RegularExpressions

- •The Regex Object

- •Using the Match Object and Matches Collection

- •Using the Match.Success Property and Match.NextMatch Method

- •The GroupCollection and Group Classes

- •The CaptureCollection and Capture Class

- •The RegexOptions Enumeration

- •Case-Insensitive Matching: The IgnoreCase Option

- •Multiline Matching: The Effect on the ^ and $ Metacharacters

- •Right to Left Matching: The RightToLeft Option

- •Lookahead and Lookbehind

- •Exercises

- •An Introductory Example

- •The Classes of System.Text.RegularExpressions

- •The Regex Class

- •The Options Property of the Regex Class

- •Regex Class Methods

- •The CompileToAssembly() Method

- •The GetGroupNames() Method

- •The GetGroupNumbers() Method

- •GroupNumberFromName() and GroupNameFromNumber() Methods

- •The IsMatch() Method

- •The Match() Method

- •The Matches() Method

- •The Replace() Method

- •The Split() Method

- •Using the Static Methods of the Regex Class

- •The IsMatch() Method as a Static

- •The Match() Method as a Static

- •The Matches() Method as a Static

- •The Replace() Method as a Static

- •The Split() Method as a Static

- •The Match and Matches Classes

- •The Match Class

- •The GroupCollection and Group Classes

- •The RegexOptions Class

- •The IgnorePatternWhitespace Option

- •Metacharacters Supported in Visual C# .NET

- •Using Named Groups

- •Using Back References

- •Exercise

- •The ereg() Set of Functions

- •The ereg() Function

- •The ereg() Function with Three Arguments

- •The eregi() Function

- •The ereg_replace() Function

- •The eregi_replace() Function

- •The split() Function

- •The spliti() Function

- •The sql_regcase() Function

- •Perl Compatible Regular Expressions

- •Pattern Delimiters in PCRE

- •Escaping Pattern Delimiters

- •Matching Modifiers in PCRE

- •Using the preg_match() Function

- •Using the preg_match_all() Function

- •Using the preg_grep() Function

- •Using the preg_quote() Function

- •Using the preg_replace() Function

- •Using the preg_replace_callback() Function

- •Using the preg_split() Function

- •Supported Metacharacters with ereg()

- •Using POSIX Character Classes with PHP

- •Supported Metacharacters with PCRE

- •Positional Metacharacters

- •Character Classes in PHP

- •Documenting PHP Regular Expressions

- •Exercises

- •W3C XML Schema Basics

- •Tools for Using W3C XML Schema

- •Comparing XML Schema and DTDs

- •How Constraints Are Expressed in W3C XML Schema

- •W3C XML Schema Datatypes

- •Derivation by Restriction

- •Unicode and W3C XML Schema

- •Unicode Overview

- •Using Unicode Character Classes

- •Matching Decimal Numbers

- •Mixing Unicode Character Classes with Other Metacharacters

- •Unicode Character Blocks

- •Using Unicode Character Blocks

- •Metacharacters Supported in W3C XML Schema

- •Positional Metacharacters

- •Matching Numeric Digits

- •Alternation

- •Using the \w and \s Metacharacters

- •Escaping Metacharacters

- •Exercises

- •Introduction to the java.util.regex Package

- •Obtaining and Installing Java

- •The Pattern Class

- •Using the matches() Method Statically

- •Two Simple Java Examples

- •The Properties (Fields) of the Pattern Class

- •The CASE_INSENSITIVE Flag

- •Using the COMMENTS Flag

- •The DOTALL Flag

- •The MULTILINE Flag

- •The UNICODE_CASE Flag

- •The UNIX_LINES Flag

- •The Methods of the Pattern Class

- •The compile() Method

- •The flags() Method

- •The matcher() Method

- •The matches() Method

- •The pattern() Method

- •The split() Method

- •The Matcher Class

- •The appendReplacement() Method

- •The appendTail() Method

- •The end() Method

- •The find() Method

- •The group() Method

- •The groupCount() Method

- •The lookingAt() Method

- •The matches() Method

- •The pattern() Method

- •The replaceAll() Method

- •The replaceFirst() Method

- •The reset() Method

- •The start() Method

- •The PatternSyntaxException Class

- •Using the \d Metacharacter

- •Character Classes

- •The POSIX Character Classes in the java.util.regex Package

- •Unicode Character Classes and Character Blocks

- •Using Escaped Characters

- •Using Methods of the String Class

- •Using the matches() Method

- •Using the replaceFirst() Method

- •Using the replaceAll() Method

- •Using the split() Method

- •Exercises

- •Obtaining and Installing Perl

- •Creating a Simple Perl Program

- •Basics of Perl Regular Expression Usage

- •Using the m// Operator

- •Using Other Regular Expression Delimiters

- •Matching Using Variable Substitution

- •Using the s/// Operator

- •Using s/// with the Global Modifier

- •Using s/// with the Default Variable

- •Using the split Operator

- •Using Quantifiers in Perl

- •Using Positional Metacharacters

- •Captured Groups in Perl

- •Using Back References in Perl

- •Using Alternation

- •Using Character Classes in Perl

- •Using Lookahead

- •Using Lookbehind

- •Escaping Metacharacters

- •A Simple Perl Regex Tester

- •Exercises

- •Index

Regular Expressions in Perl

Basics of Perl Regular Expression Usage

This section illustrates straightforward uses of regular expressions in Perl, for those readers who are not fluent in Perl. This chapter does not provide a full tutorial on how to use Perl. If you have little or no knowledge of Perl, I suggest that if you want to use regular expressions in real Perl applications, you take time to study a book such as Perl For Dummies, by Paul Hoffman (Wiley 2003).

To use regular expressions in Perl, you must use one or more of the regular expression operators.

Using the Perl Regular Expression

Operators

The Perl regular expression operators interact intimately with regular expression patterns. The following table lists and briefly describes the regular expression operators.

Operator |

Description |

|

|

m// |

Used when matching a string against a regular expression |

s/// |

Used when matching and then substituting a pattern |

q// etc |

Generalized quotes |

split// |

Splits a string into a list of strings |

The simplest operator is the m// operator, which is used to test if there is a match between a string and a regular expression. As you will see later, the m of the m// operator isn’t essential in Perl code. However, I suggest that you use it routinely, because it makes clearer what is happening in the matching process.

Using the m// Operator

The m// operator is used together with the =~ operator to test whether a string contains a match for a specified regular expression.

Try It Out |

Using the m// Operator |

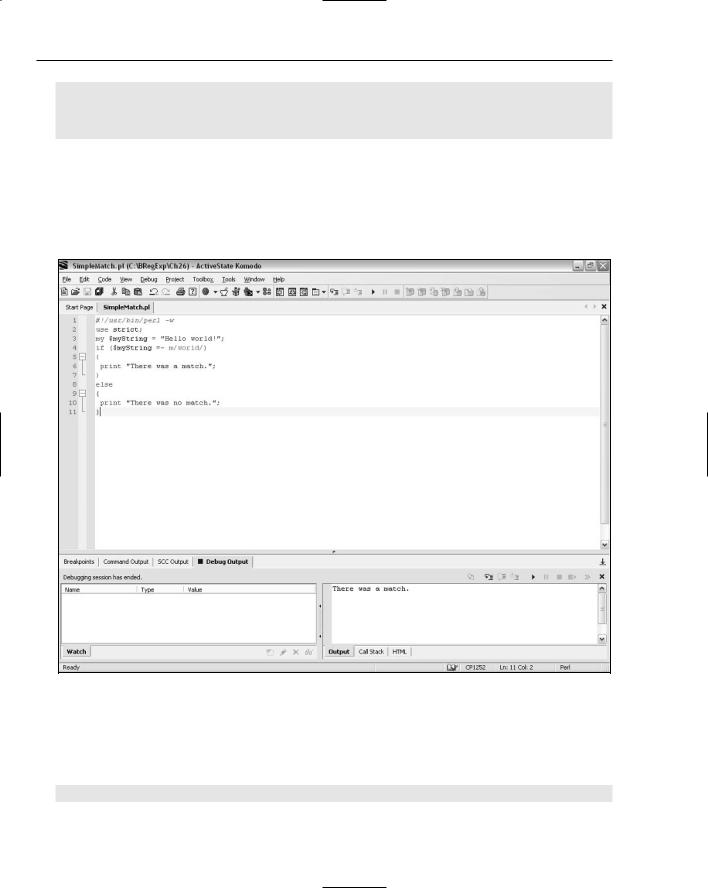

1.Create a new Perl file in Komodo 3.0 or in your chosen text editor, and edit the code to read as follows:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict;

my $myString = “Hello world!”; if ($myString =~ m/world/)

{

print “There was a match.”;

}

667

Chapter 26

else

{

print “There was no match.”;

}

2.Save the code as SimpleMatch.pl.

3.Press F5, use the Browse button to select SimpleMatch.pl, and press Return to run the code in debug mode.

4.Inspect the results displayed in the Output pane (in the lower-right corner of the Komodo window), as shown in Figure 26-9. The displayed message simply states that a match was found.

Figure 26-9

How It Works

First, the string value Hello world! was assigned to the $myString variable, as before. Because the strict pragma is in force, you add a my before the variable name:

my $myString = “Hello world!”;

668

Regular Expressions in Perl

Then an if statement is used to determine whether a message indicating successful matching or failed matching is to be displayed. The test of the if statement is whether or not the $myString variable contains a match for the literal regular expression pattern world. The combination of the =~ operator and the m// operator can be read as matches.

Perl doesn’t have a Boolean datatype, but it behaves as though it does:

if ($myString =~ m/world/)

By default, matching in Perl is case sensitive.

If a match is found (there is a match, given the code in this example file), a message is displayed indicating that matching was successful. In Perl, the paired curly braces are required to enclose the statement block that is executed when the test returns the equivalent of true, even if only a single statement is to be executed:

{

print “There was a match.”;

}

If no match is found, a message to that effect is displayed. Again, the paired curly braces of the else clause are required, even though there is only a single statement in the else statement block:

else

{

print “There was no match.”;

}

The m// operator can be used with any of the regular expression matching modes that Perl supports. The following example shows how matching can be carried out case insensitively. The case-insensitive matching mode is indicated by a lowercase i following the second forward slash of the paired forward slashes that delimit the regular expression pattern:

$myTestString =~ m/world/i;

The example also introduces a very useful function, chomp, which you will use often in code that accepts input from the user.

Try It Out |

Matching Case Insensitively |

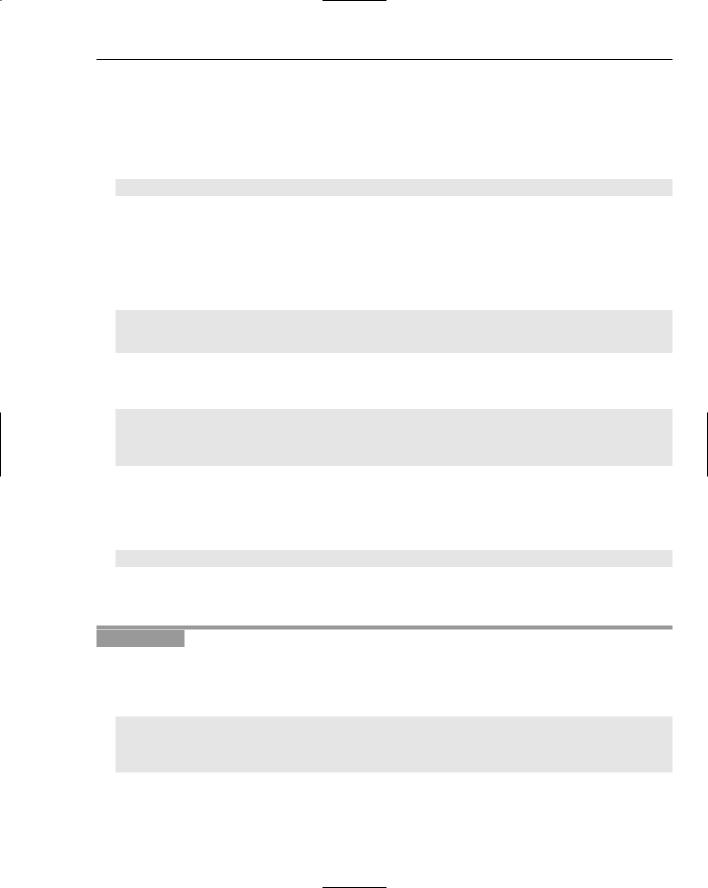

1.Type the following code in Komodo or your chosen text editor, and save the code as

MatchInsensitive.pl:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict;

print “Enter a string. It will be matched against the pattern ‘/Star/i’.\n\n”; my $myTestString = <STDIN>;

chomp($myTestString);

if ($myTestString =~ m/Star/i)

{

669

Chapter 26

print “There is a match for ‘$myTestString’.”;

}

else

{

print “No match was found in ‘$myTestString’.”;

}

2.Either run the code inside Komodo 3.0 (by pressing F5, selecting MatchInsensitive.pl using the Browse button, and then pressing the Return key) or type perl MatchInsensitive.pl at the command line.

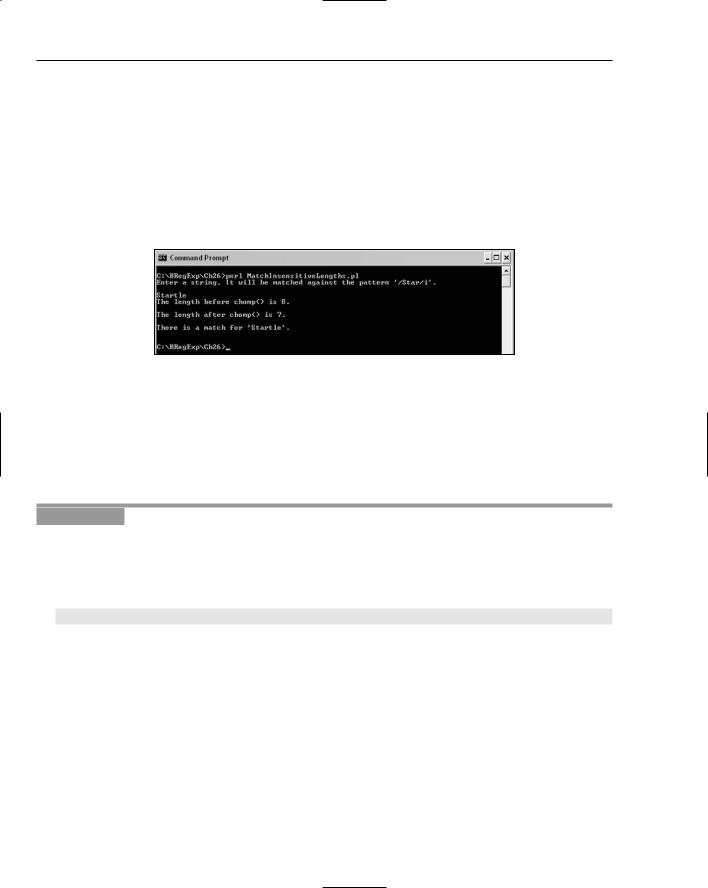

3.The first time that the code is run, enter the test string Startle, and press the Return key. Inspect the displayed message, as shown in Figure 26-10.

When entering text in the Komodo 3.0 Output pane, be sure that the focus has gone to the desired line. It is easy to type characters unintentionally into the Code pane, rather than the Output pane, with a resulting avalanche of syntax errors the next time you attempt to run the code.

Figure 26-10

670

Regular Expressions in Perl

4.Run the code again, enter the test string startle, and press the Return key. Inspect the displayed message. Again, a match is found, because the pattern Star, when matched case insensitively, matches the initial star of startle.

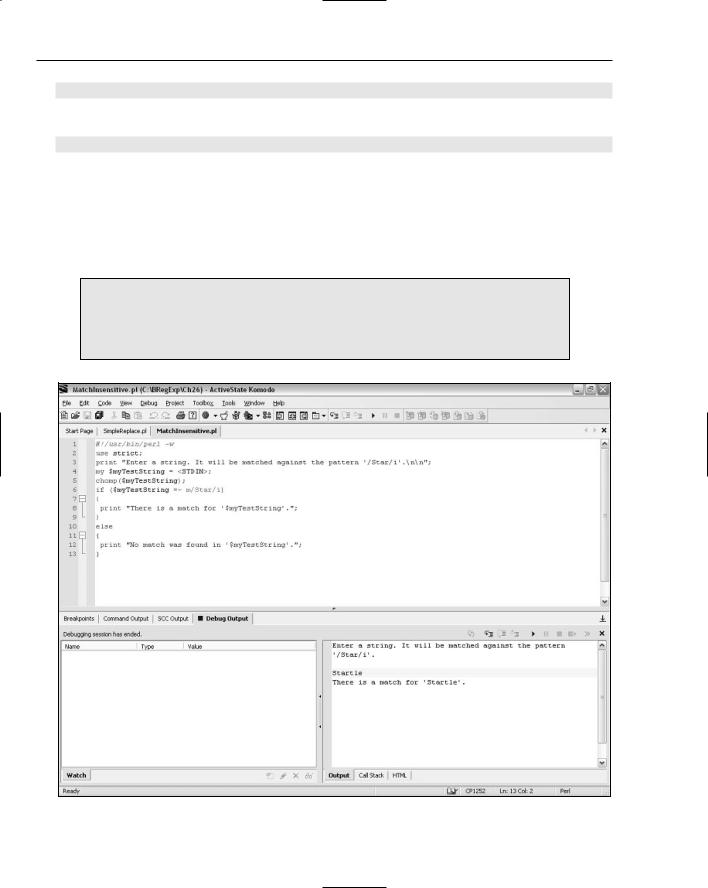

5.Run the code again, enter the test string Hello, and press the Return key. Inspect the displayed message, as shown in Figure 26-11.

Figure 26-11

How It Works

First, the print operator is used to display a message inviting the user to enter a test string:

print “Enter a string. It will be matched against the pattern ‘/Star/i’.\n\n”;

The variable $myTestString is assigned the sequence of characters that the user enters at the command line. The <STDIN> operator reads in a line of characters from the standard input. Typically, the standard input device is the keyboard. So <STDIN> reads a line of characters from the keyboard, ending when you press the Return key. One of the minor inconveniences about the line of characters provided by the standard input is that it includes the newline character. Perl treats a newline character as part of the character sequence to be matched. So the newline needs to be removed to achieve the matching behavior that you would likely expect:

my $myTestString = <STDIN>;

Perl provides the chomp operator to remove the newline character from the end of the sequence of characters that have been read in from the standard input:

chomp($myTestString);

The code file MatchInsensitiveLengths.pl, shown here and also included in the code download, displays the length of $myTestString before and after the chomp() function is used. Notice that when the test string is Startle, the length of the string is 8, one more than the number of visible characters. The newline character is the eighth character:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict;

print “Enter a string. It will be matched against the pattern ‘/Star/i’.\n\n”; my $myTestString = <STDIN>;

my $myLength = length($myTestString);

print “The length before chomp() is $myLength.\n\n”; chomp($myTestString);

$myLength = length($myTestString);

print “The length after chomp() is $myLength.\n\n”;

671

Chapter 26

if ($myTestString =~ m/Star/i)

{

print “There is a match for ‘$myTestString’.\n\n”;

}

else

{

print “No match was found in ‘$myTestString’.”;

}

Figure 26-12 shows the screen’s appearance when you run MatchInsensitiveLengths.pl from the command line. Notice the length of the $myTestString before and after chomp() is used.

Figure 26-12

One of the difficulties for beginners when using Perl is that many constructs can be written in more than one way. The next couple of examples illustrate some of these variations, which you may meet when you have to handle code created by other developers.

The character m in the m// operator is, in fact, optional. I suggest, for the sake of clarity (the m hints at the idea of matching), that you use m// rather than just //, as in the following example.

Try It Out |

Optional “m” |

1.Type the following code in Komodo 3.0 or an alternative text editor, and save the code as

SimpleMatchNoM.pl:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict;

my $myString = “Hello world!”; if ($myString =~ /world/)

{

print “There was a match.”;

}

else

{

print “There was no match.”;

}

2.Press F5 and then press the Return key to run the code.

3.Inspect the result. Because the behavior of matching with // instead of m// is no different, the screen’s appearance is the same as was shown in Figure 26-9.

672

Regular Expressions in Perl

The chomp() function is something you are likely to use frequently, because it is useful to remove the newline character that ends a line of user input. The following example shows an alternative syntax for chomp() which, while less obvious to occasional Perl programmers, is more succinct.

Try It Out |

An Alternative chomp() Syntax |

1.Type the following code in Komodo 3.0 or an alternative text editor, and save the code as

MatchAlternativeChomp.pl:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict;

print “Enter a string. It will be matched against the pattern ‘/Star/i’.\n\n”; chomp (my $myTestString = <STDIN>);

if ($myTestString =~ m/Star/i)

{

print “There is a match for ‘$myTestString’.”;

}

else

{

print “No match was found in ‘$myTestString’.”;

}

2.Run the code inside Komodo or, at the command line, type perl MatchAlternativeChomp.pl.

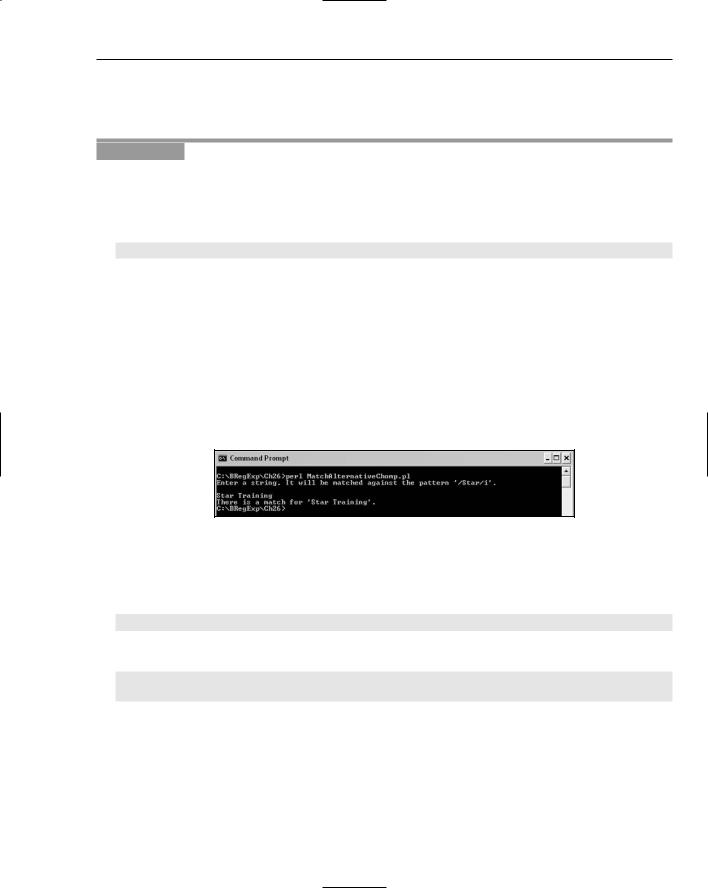

3.Enter the test string Star Training, and press the Return key. Inspect the displayed results, as shown in Figure 26-13.

Figure 26-13

How It Works

The line of code:

chomp (my $myTestString = <STDIN>);

is functionally equivalent to:

my $myTestString = <STDIN>;

chomp ($myTestString);

The precedence of the assignment operator, =, means that the assignment happens first; then, when that assignment has taken place, the chomp() function is applied.

673

Chapter 26

There are also variants in how the print function can be used. It is possible to use the print operator conditionally in the following way. The following code is included in the file MatchAlternativeChomp2.pl in the code download:

print “Enter a string. It will be matched against the pattern ‘/Star/i’.\n\n”;

chomp (my $myTestString = <STDIN>);

The if statement is included in the same line as the print operator after the string to be printed:

print “There is a match for ‘$myTestString’.” if ($myTestString =~ m/Star/i);

The !~ operator in the test for the if statement means “There is not a match”:

print “There is no match for ‘$myTestString’.” if ($myTestString !~ m/Star/i);

It isn’t necessary to express the pattern to match against as a string. You have the option to match against a variable. Matching against a variable is useful when you want to match against the same pattern more than once in your code.

Try It Out |

Matching Against a Variable |

1.Type the following code in your chosen editor, and save the code as MatchUsingVariable.pl:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict;

my $myPattern = “^\\d{5}(-\\d{4})?\$”; print “Enter a US Zip Code: “;

my $myTestString = <STDIN>; chomp ($myTestString);

print “You entered a Zip code.\n\n” if ($myTestString =~ m/$myPattern/);

print “The value you entered wasn’t recognized as a US Zip code.” if ($myTestString !~ m/$myPattern/);

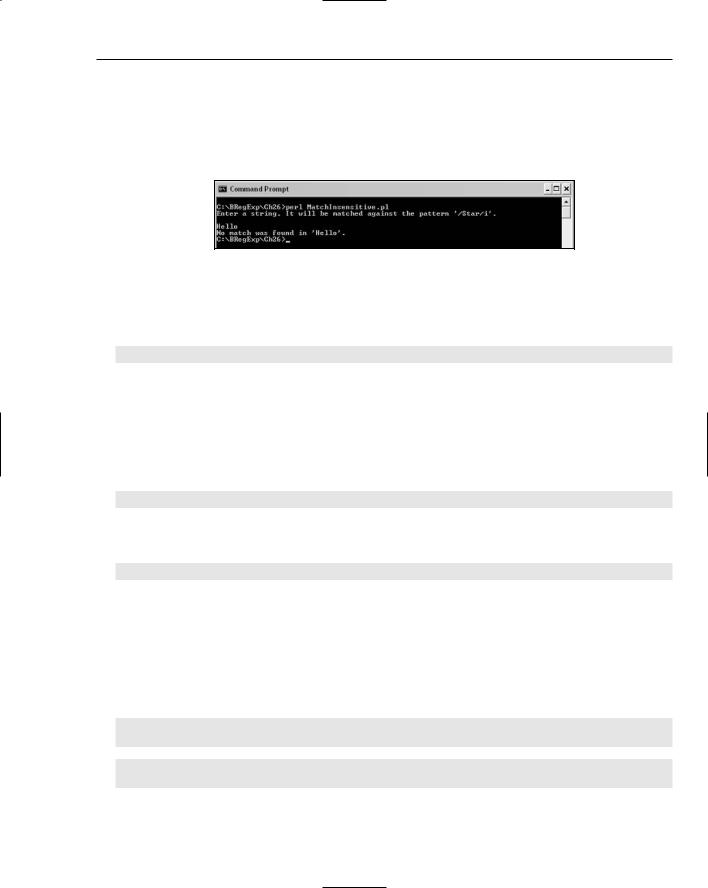

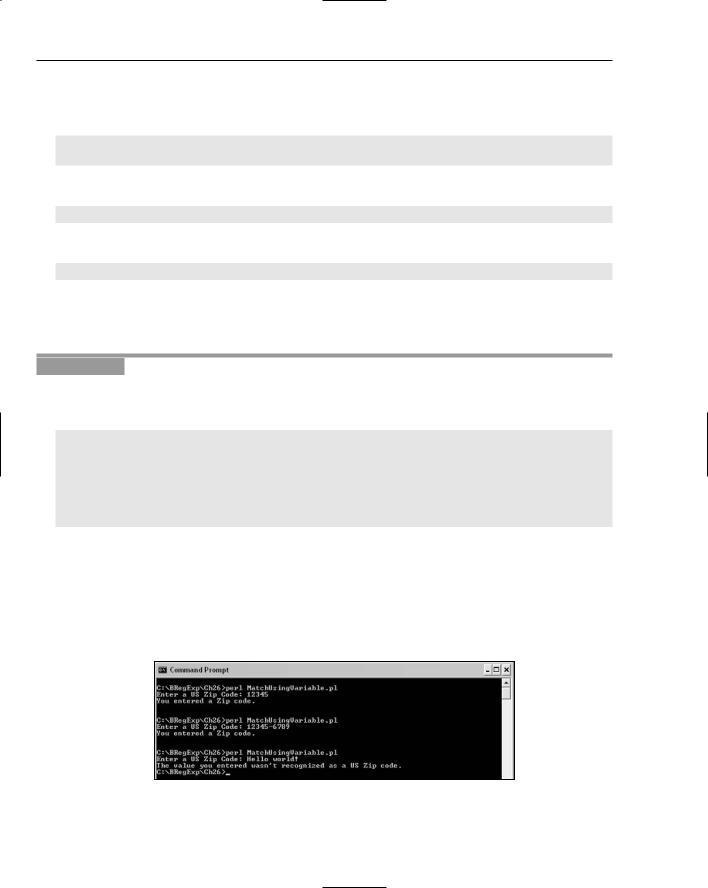

2.Run the code in Komodo or at the command line. When prompted, enter the test string 12345, and inspect the displayed result.

3.Run the code again (F3 if you are using the Windows command line). When prompted, enter the test string 12345-6789, and inspect the displayed result.

4.Run the code again. When prompted, enter the test string Hello world! and inspect the result, as shown in Figure 26-14.

Figure 26-14

674