- •About the Author

- •Dedication

- •Author’s Acknowledgments

- •Contents at a Glance

- •Table of Contents

- •Introduction

- •Who Should Buy This Book

- •How This Book Is Organized

- •Part I: Programming a Computer

- •Part II: Learning Programming with Liberty BASIC

- •Part III: Advanced Programming with Liberty BASIC

- •Part VI: Internet Programming

- •Part VII: The Part of Tens

- •How to Use This Book

- •Foolish assumptions

- •Icons used in this book

- •Why Learn Computer Programming?

- •How Does a Computer Program Work?

- •What Do I Need to Know to Program a Computer?

- •The joy of assembly language

- •C: The portable assembler

- •High-level programming languages

- •Database programming languages

- •Scripting programming languages

- •The program’s users

- •The target computer

- •Prototyping

- •Choosing a programming language

- •Defining how the program should work

- •The Life Cycle of a Typical Program

- •The development cycle

- •The maintenance cycle

- •The upgrade cycle

- •Writing Programs in an Editor

- •Using a Compiler or an Interpreter

- •Compilers

- •Interpreters

- •P-code: A combination compiler and interpreter

- •So what do I use?

- •Squashing Bugs with a Debugger

- •Writing a Help File

- •Creating an Installation Program

- •Why Learn Liberty BASIC?

- •Liberty BASIC is easy

- •Liberty BASIC runs on Windows

- •You can start using Liberty BASIC today

- •Installing Liberty BASIC

- •Loading Liberty BASIC

- •Your First Liberty BASIC Program

- •Running a Liberty BASIC program

- •Saving a Liberty BASIC program

- •Getting Help Using Liberty BASIC

- •Exiting Liberty BASIC

- •Getting input

- •Displaying output

- •Sending Data to the Printer

- •Storing Data in Variables

- •Creating a variable

- •Assigning a value to a variable

- •Declaring your variables

- •Using Constants

- •Commenting Your Code

- •Using variables

- •Working with precedence

- •Using parentheses

- •Manipulating Strings

- •Declaring variables as strings

- •Smashing strings together

- •Counting the length of a string

- •Playing with UPPERCASE and lowercase

- •Trimming the front and back of a string

- •Inserting spaces

- •Yanking characters out of a string

- •Looking for a string inside another string

- •Using Boolean Expressions

- •Using variables in Boolean expressions

- •Using Boolean operators

- •Exploring IF THEN Statements

- •IF THEN ELSE statements

- •Working with SELECT CASE Statements

- •Checking a range of values

- •Checking a relational operator

- •Boolean expression inside the loop

- •Looping a Fixed Number of Times

- •Counting with different numbers

- •Counting in increments

- •Anatomy of a Computer Bug

- •Syntax Errors

- •Fun with Logic Errors

- •Stepping line by line

- •Tracing through your program

- •Designing a Window

- •Creating a new window

- •Defining the size and location of a window

- •Adding color to a window

- •Putting Controls in a Window

- •Creating a command button

- •Displaying text

- •Creating a check box

- •Creating a radio button

- •Creating text boxes

- •Creating list boxes

- •Creating combo boxes

- •Creating group boxes

- •Storing Stuff in Text Files

- •Creating a new text file

- •Putting stuff in a text file

- •Adding new stuff to an existing text file

- •Retrieving data from a text file

- •Creating a new binary file

- •Saving stuff in a binary file

- •Changing stuff in a binary file

- •Retrieving stuff from a binary file

- •Creating a Graphics Control

- •Using Turtle Graphics

- •Defining line thickness

- •Defining line colors

- •Drawing Circles

- •Drawing Boxes

- •Displaying Text

- •Making Sounds

- •Making a beeping noise

- •Playing WAV files

- •Passing Data by Value or by Reference

- •Using Functions

- •Defining a function

- •Passing data to a function

- •Calling a function

- •Exiting prematurely from a function

- •Using Subroutines

- •Defining a subroutine

- •Passing data to a subroutine

- •Calling a subroutine

- •Exiting prematurely from a subroutine

- •Writing Modular Programs

- •Introducing Structured Programming

- •Sequential instructions

- •Branching instructions

- •Looping instructions

- •Putting structured programming into practice

- •The Problem with Software

- •Ways to Make Programming Easier

- •Breaking Programs into Objects

- •How to use objects

- •How to create an object

- •Creating an object

- •Starting with a Pointer

- •Defining the parts of a linked list

- •Creating a linked list

- •Managing a linked list

- •Making Data Structures with Linked Lists

- •Stacks

- •Queues

- •Trees

- •Graphs

- •Creating a Record

- •Manipulating Data in Records

- •Storing data in a record

- •Retrieving data from a record

- •Using Records with Arrays

- •Making an Array

- •Making a Multidimensional Array

- •Creating Dynamic Arrays

- •Insertion Sort

- •Bubble Sort

- •Shell Sort

- •Quicksort

- •Sorting Algorithms

- •Searching Sequentially

- •Performing a Binary Search

- •Hashing

- •Searching by using a hash function

- •Dealing with collisions

- •Picking a Searching Algorithm

- •Choosing the Right Data Structure

- •Choosing the Right Algorithm

- •Put the condition most likely to be false first

- •Put the condition most likely to be true first

- •Clean out your loops

- •Use the correct data types

- •Using a Faster Language

- •Optimizing Your Compiler

- •Programming Computer Games

- •Creating Computer Animation

- •Making (And Breaking) Encryption

- •Internet Programming

- •Fighting Computer Viruses and Worms

- •Hacking for Hire

- •Participating in an Open-Source Project

- •Niche-Market Programming

- •Teaching Others about Computers

- •Selling Your Own Software

- •Trying Commercial Compilers

- •Windows programming

- •Macintosh and Palm OS programming

- •Linux programming

- •Testing the Shareware and

- •BASIC compilers

- •C/C++ and Java compilers

- •Pascal compilers

- •Using a Proprietary Language

- •HyperCard

- •Revolution

- •PowerBuilder

- •Shopping by Mail Order

- •Getting Your Hands on Source Code

- •Joining a Local User Group

- •Frequenting Usenet Newsgroups

- •Playing Core War

- •Programming a Battling Robot

- •Toying with Lego Mindstorms

- •Index

- •End-User License Agreement

200 Part III: Advanced Programming with Liberty BASIC

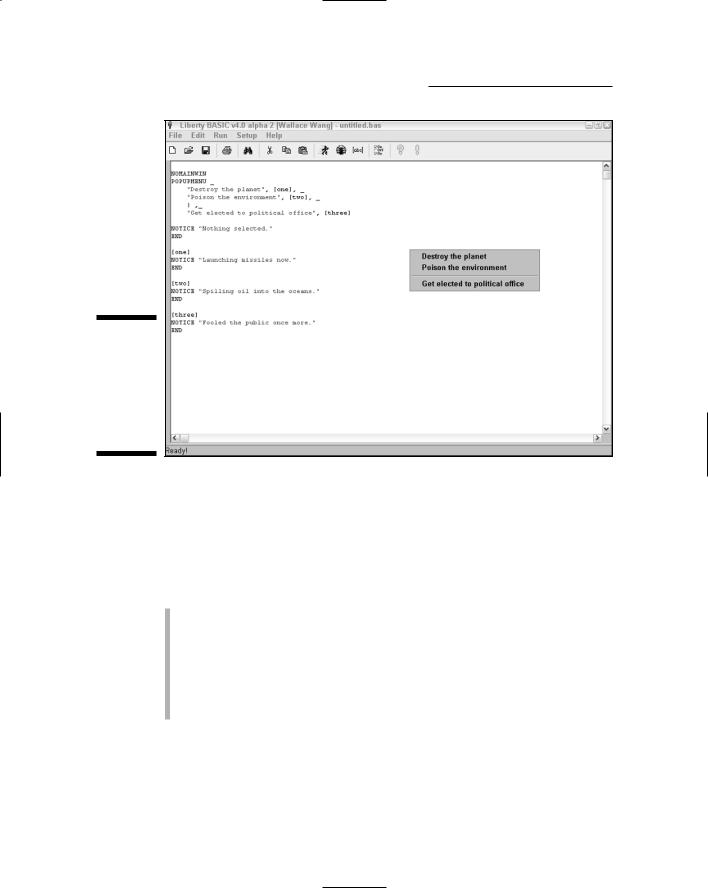

Figure 14-3:

Pop-up menus can provide additional options for users to choose.

Putting Controls in a Window

Although you commonly use pull-down menus to get commands from the user, you may also want to add command buttons, check boxes, radio buttons, and text boxes to a window. In placing such controls as command buttons on a window, you need to define the following:

A name to identify the control

Text to appear on the control

A label to identify instructions for the computer to follow after the user chooses that particular control

The width and height of the control

The position of the control

Creating a command button

A command button usually appears on-screen as a gray rectangle containing a label such as OK or Cancel. To create a command button, you need to use the BUTTON command, as follows:

Chapter 14: Creating a User Interface 201

BUTTON #Windowhandle.buttonname, “Button text”,

[branchLabel], UL, xpos, ypos, width, height

If you omit the width and height, the button automatically adjusts to the size of the text that you want to appear on the button.

Here’s how the following command works:

1.The BUTTON command tells the computer, “Create a command button inside the window that the nickname #Windowhandle identifies.”

2.The buttonname portion tells the computer, “Identify this button by this unique name.”

3.The Button text portion is the text that actually appears on the button.

4.The [branchLabel] portion identifies a label to which the computer jumps to find instructions to follow after the user clicks the button.

5.The UL portion tells the computer, “Position the command button by using the upper-left corner of the window.” Instead of using UL, you can also use UR (upper-right), LL (lower-left), or LR (lower-right).

6.The xpos and ypos portions represent the X and Y position of the button’s location, which you measure in pixels from the upper-left (UL), upper-right (UR), lower-left (LL), or lower-right (LR) edge of the window.

7.The width and height portions define the width and height of the button.

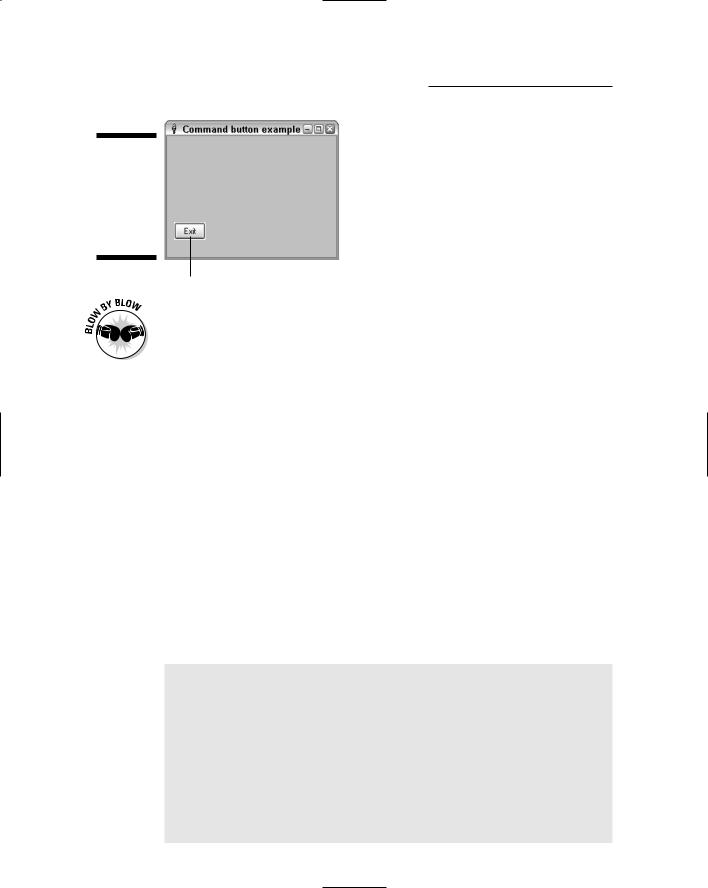

To see how this button works in a real-life example, run the following program, the results of which are shown in Figure 14-4:

NOMAINWIN WindowHeight = 200 WindowWidth = 250

BUTTON #main.mybutton, “E&xit”, [quit], LL, 10, 10, 45, 25 OPEN “Command button example” FOR WINDOW AS #main

PRINT #main, “trapclose [quit]” WAIT

[quit]

CONFIRM “Are you sure you want to quit?”; quit$ IF quit$ = “no” THEN WAIT

CLOSE #main END

As an alternative to creating a command button, Liberty BASIC also enables you to use a bitmap image as a button. To turn a bitmap image into a button, you need to use the BMPBUTTON command, as follows:

BMPBUTTON #Windowhandle.buttonname, “bitmap filename”,

[branchLabel], UL, xpos, ypos

202 Part III: Advanced Programming with Liberty BASIC

Figure 14-4:

If you create a command button, define its size and position.

Command button

Here’s what the preceding command does:

1.The BMPBUTTON command tells the computer, “Create a button out of a bitmap image and display this image inside the window that the nickname

#Windowhandle identifies.”

2.The buttonname portion tells the computer, “Identify this bitmap button by this unique name.”

3.The “bitmap filename” portion defines the directory and filename of the bitmap image that you want to use, such as C:\Liberty\face.bmp.

4.The [branchLabel] portion identifies a label to which the computer jumps to find instructions to follow after the user clicks the bitmap button.

5.The UL portion tells the computer, “Position the bitmap button by using the upper-left corner of the window.” Instead of using UL, you can also use UR (upper-right), LL (lower-left), or LR (lower-right).

6.The xpos and ypos portions represent the X and Y position of the bitmap button’s location, which you measure in pixels from the upper-left (UL), upper-right (UR), lower-left (LL), or lower-right (LR) edge of the window.

To see how this button works in a real-life example, try running the following program:

NOMAINWIN WindowWidth = 400

BMPBUTTON #main.picturebtn, “vwsignon.bmp”, [Exit], UL, 10, 40

OPEN “Bitmap Button Example” FOR WINDOW AS #main PRINT #main, “trapclose [quit]”

WAIT

[quit]

CONFIRM “Are you sure you want to quit?”; quit$ IF quit$ = “no” THEN WAIT

CLOSE #main END

Chapter 14: Creating a User Interface 203

Displaying text

Sometimes you may want to display text inside a window to display a message or give instructions to the user. In Liberty BASIC, text that the user can’t change is known as static text, which you can create by using the STATICTEXT command, as follows:

STATICTEXT #Windowhandle.staticname, “Static text”, xpos,

ypos, width, height

Here’s what the preceding command does:

1.The STATICTEXT command tells the computer, “Display text inside a window that the nickname #Windowhandle identifies. Identify the static text by the name staticname.”

2.The “Static text” portion tells the computer, “Display inside the window whatever text appears inside double quotes.”

3.The xpos and ypos portions represent the X and Y position of the static text’s location, which you measure in pixels from the upper-left edge of the window.

4.The width and height portions represent the width and height of the static text, which you also measure in pixels.

You can change text inside static text by using the PRINT command, as follows:

PRINT #Windowhandle.staticname, “New text”

To try out a real program, try the following example:

NOMAINWIN

STATICTEXT #main.static, “Old text”, 10, 10, 75, 25

BUTTON #main.mybutton, “Change”, [change], LL, 10, 10, 45, 25 OPEN “Real-life example” FOR Window AS #main

PRINT #main, “trapclose [quit]” WAIT

[change]

PRINT #main.static, “New text”

WAIT

[quit]

CONFIRM “Are you sure you want to quit?”; quit$ IF quit$ = “no” THEN WAIT

CLOSE #main END

This program displays static text in a window that reads Old text. After you click the Change command button, the static text changes and displays

New text.