- •Microsoft C# Programming for the Absolute Beginner

- •Table of Contents

- •Microsoft C# Programming for the Absolute Beginner

- •Introduction

- •Overview

- •Chapter 1: Basic Input and Output: A Mini Adventure

- •Project: The Mini Adventure

- •Reviewing Basic C# Concepts

- •Namespaces

- •Classes

- •Methods

- •Statements

- •The Console Object

- •.NET Documentation

- •Getting into the Visual Studio .Net Environment

- •Examining the Default Code

- •Creating a Custom Namespace

- •Adding Summary Comments

- •Creating the Class

- •Moving from Code to a Program

- •Compiling Your Program

- •Looking for Bugs

- •Getting Input from the User

- •Creating a String Variable

- •Getting a Value with the Console.ReadLine() Method

- •Incorporating a Variable in Output

- •Combining String Values

- •Combining Strings with Concatenation

- •Adding a Tab Character

- •Using the Newline Sequence

- •Displaying a Backslash

- •Displaying Quotation Marks

- •Launching the Mini Adventure

- •Planning the Story

- •Creating the Variables

- •Getting Values from the User

- •Writing the Output

- •Finishing the Program

- •Summary

- •Chapter 2: Branching and Operators: The Math Game

- •The Math Game

- •Using Numeric Variables

- •The Simple Math Game

- •Numeric Variable Types

- •Integer Variables

- •Long Integers

- •Data Type Problems

- •Math Operators

- •Converting Variables

- •Explicit Casting

- •The Convert Object

- •Creating a Branch in Program Logic

- •The Hi Bill Game

- •Condition Testing

- •The If Statement

- •The Else Clause

- •Multiple Conditions

- •Working with The Switch Statement

- •The Switch Demo Program

- •Examining How Switch Statements Work

- •Creating a Random Number

- •Introducing the Die Roller

- •Exploring the Random Object

- •Creating a Random Double with the .NextDouble() Method

- •Getting the Values of Dice

- •Creating the Math Game

- •Designing the Game

- •Creating the Variables

- •Managing Addition

- •Managing Subtraction

- •Managing Multiplication and Division

- •Checking the Answers

- •Waiting for the Carriage Return

- •Summary

- •Chapter 3: Loops and Strings: The Pig Latin Program

- •Project: The Pig Latin Program

- •Investigating The String Object

- •The String Mangler Program

- •A Closer Look at Strings

- •Using the Object Browser

- •Experimenting with String Methods

- •Performing Common String Manipulations

- •Using a For Loop

- •Examining The Bean Counter Program

- •Creating a Sentry Variable

- •Checking for an Upper Limit

- •Incrementing the Variable

- •Examining the Behavior of the For Loop

- •The Fancy Beans Program

- •Skipping Numbers

- •Counting Backwards

- •Using a Foreach Loop to Break Up a Sentence

- •Using a While Loop

- •The Magic Word Program

- •Writing an Effective While Loop

- •Planning Your Program with the STAIR Process

- •S: State the Problem

- •T: Tool Identification

- •A: Algorithm

- •I: Implementation

- •R: Refinement

- •Applying STAIR to the Pig Latin Program

- •Stating the Problem

- •Identifying the Tools

- •Creating the Algorithm

- •Implementing and Refining

- •Writing the Pig Latin Program

- •Setting Up the Variables

- •Creating the Outside Loop

- •Dividing the Phrase into Words

- •Extracting the First Character

- •Checking for a Vowel

- •Adding Debugging Code

- •Closing Up the code

- •Summary

- •Introducing the Critter Program

- •Creating Methods to Reuse Code

- •The Song Program

- •Building the Main() Method

- •Creating a Simple Method

- •Adding a Parameter

- •Returning a Value

- •Creating a Menu

- •Creating a Main Loop

- •Creating the Sentry Variable

- •Calling a Method

- •Working with the Results

- •Writing the showMenu() Method

- •Getting Input from the User

- •Handling Exceptions

- •Returning a Value

- •Creating a New Object with the CritterName Program

- •Creating the Basic Critter

- •Using Scope Modifiers

- •Using a Public Instance Variable

- •Creating an Instance of the Critter

- •Adding a Method

- •Creating the talk() Method for the CritterTalk Program

- •Changing the Menu to Use the talk() Method

- •Creating a Property in the CritterProp Program

- •Examining the Critter Prop Program

- •Creating the Critter with a Name Property

- •Using Properties as Filters

- •Making the Critter More Lifelike

- •Adding More Private Variables

- •Adding the Age() Method

- •Adding the Eat() Method

- •Adding the Play() Method

- •Modifying the Talk() Method

- •Making Changes in the Main Class

- •Summary

- •Introducing the Snowball Fight

- •Inheritance and Encapsulation

- •Creating a Constructor

- •Adding a Constructor to the Critter Class

- •Creating the CritViewer Class

- •Reviewing the Static Keyword

- •Calling a Constructor from the Main() Method

- •Working with Multiple Files

- •Overloading Constructors

- •Viewing the Improved Critter Class

- •Adding Polymorphism to Your Objects

- •Modifying the Critter Viewer in CritOver to Demonstrate Overloaded Constructors

- •Using Inheritance to Make New Classes

- •Creating a Class to View the Clone

- •Creating the Critter Class

- •Improving an Existing Class

- •Introducing the Glitter Critter

- •Adding Methods to a New Class

- •Changing the Critter Viewer Again

- •Creating the Snowball Fight

- •Building the Fighter

- •Building the Robot Fighter

- •Creating the Main Menu Class

- •Summary

- •Overview

- •Introducing the Visual Critter

- •Thinking Like a GUI Programmer

- •Creating a Graphical User Interface (GUI)

- •Examining the Code of a Windows Program

- •Adding New Namespaces

- •Creating the Form Object

- •Creating a Destructor

- •Creating the Components

- •Setting Component Properties

- •Setting Up the Form

- •Writing the Main() Method

- •Creating an Interactive Program

- •Responding to a Simple Event

- •Creating and Adding the Components

- •Adding an Event to the Program

- •Creating an Event Handler

- •Allowing for Multiple Selections

- •Choosing a Font with Selection Controls

- •Creating the User Interface

- •Examining Selection Tools

- •Creating Instance Variables in the Font Chooser

- •Writing the AssignFont() Method

- •Writing the Event Handlers

- •Working with Images and Scroll Bars

- •Setting Up the Picture Box

- •Adding a Scroll Bar

- •Revisiting the Visual Critter

- •Designing the Program

- •Determining the Necessary Tools

- •Designing the Form

- •Writing the Code

- •Summary

- •Chapter 7: Timers and Animation: The Lunar Lander

- •Introducing the Lunar Lander

- •Reading Values from the Keyboard

- •Introducing the Key Reader Program

- •Setting Up the Key Reader Program

- •Coding the KeyPress Event

- •Coding the KeyDown Event

- •Determining Which Key Was Pressed

- •Animating Images

- •Introducing the ImageList Control

- •Setting Up an Image List

- •Looking at the Image Collection

- •Displaying an Image from the Image List

- •Using a Timer to Automate Animation

- •Introducing the Timer Control

- •Configuring the Timer

- •Adding Motion

- •Checking for Keyboard Input

- •Working with the Location Property

- •Detecting Collisions between Objects

- •Coding the Crasher Program

- •Getting Values for newX and newY

- •Bouncing the Ball off the Sides

- •Checking for Collisions

- •Extracting a Rectangle from a Component

- •Getting More from the MessageBox Object

- •Introducing the MsgDemo Program

- •Retrieving Values from the MessageBox

- •Coding the Lunar Lander

- •The Visual Design

- •The Constructor

- •The timer1_Tick() Method

- •The moveShip() Method

- •The checkLanding() Method

- •The theForm_KeyDown() Method

- •The showStats() Method

- •The killShip() Method

- •The initGame() Method

- •Summary

- •Chapter 8: Arrays: The Soccer Game

- •The Soccer Game

- •Introducing Arrays

- •Exploring the Counter Program

- •Creating an Array of Strings

- •Referring to Elements in an Array

- •Working with Arrays

- •Using the Array Demo Program to Explore Arrays

- •Building the Languages Array

- •Sorting the Array

- •Designing the Soccer Game

- •Solving a Subset of the Problem

- •Adding Percentages for the Other Players

- •Setting Up the Shot Demo Program

- •Setting Up the List Boxes

- •Using a Custom Event Handler

- •Writing the changeStatus() Method

- •Kicking the Ball

- •Designing Programs by Hand

- •Examining the Form by Hand Program

- •Adding Components in the Constructor

- •Responding to the Button Event

- •Building the Soccer Program

- •Setting Up the Variables

- •Examining the Constructor

- •Setting Up the Players

- •Setting Up the Opponents

- •Setting Up the Goalies

- •Responding to Player Clicks

- •Handling Good Shots

- •Handling Bad Shots

- •Setting a New Current Player

- •Handling the Passage of Time

- •Updating the Score

- •Summary

- •Chapter 9: File Handling: The Adventure Kit

- •Introducing the Adventure Kit

- •Viewing the Main Screen

- •Loading an Adventure

- •Playing an Adventure

- •Creating an Adventure

- •Reading and Writing Text Files

- •Exploring the File IO Program

- •Importing the IO Namespace

- •Writing to a Stream

- •Reading from a Stream

- •Creating Menus

- •Exploring the Menu Demo Program

- •Adding a MainMenu Object

- •Adding a Submenu

- •Setting Up the Properties of Menu Items

- •Writing Event Code for Menus

- •Using Dialog Boxes to Enhance Your Programs

- •Exploring the Dialog Demo Program

- •Adding Standard Dialogs to Your Form

- •Using the File Dialog Controls

- •Responding to File Dialog Events

- •Using the Font Dialog Control

- •Using the Color Dialog Control

- •Storing Entire Objects with Serialization

- •Exploring the Serialization Demo Program

- •Creating the Contact Class

- •Referencing the Serializable Namespace

- •Storing a Class

- •Retrieving a Class

- •Returning to the Adventure Kit Program

- •Examining the Room Class

- •Creating the Dungeon Class

- •Writing the Game Class

- •Writing the Editor Class

- •Writing the MainForm Class

- •Summary

- •Chapter 10: Chapter Basic XML: The Quiz Maker

- •Introducing the Quiz Maker Game

- •Taking a Quiz

- •Creating and Editing Quizzes

- •Investigating XML

- •Defining XML

- •Creating an XML Document in .NET

- •Creating an XML Schema for Your Language

- •Investigating the .NET View of XML

- •Exploring the XmlNode Class

- •Exploring the XmlDocument Class

- •Reading an Existing XML Document

- •Creating the XML Viewer Program

- •Writing New Values to an XML Document

- •Building the Document Structure

- •Adding an Element to the Document

- •Displaying the XML Code

- •Examining the Quizzer Program

- •Building the Main Form

- •Writing the Quiz Form

- •Writing the Editor Form

- •Summary

- •Overview

- •Introducing the SpyMaster Program

- •Creating a Simple Database

- •Accessing the Data Server

- •Accessing the Data in a Program

- •Using Queries to Modify Data Results

- •Limiting Data with the SELECT Statement

- •Using an Existing Database

- •Adding the Capability to Display Queries

- •Creating a Visual Query Builder

- •Working with Relational Databases

- •Improving Your Data with Normalization

- •Using a Join to Connect Two Tables

- •Creating a View

- •Referring to a View in a Program

- •Incorporating the Agent Specialty Attribute

- •Working with Other Databases

- •Creating a New Connection

- •Converting a Data Set to XML

- •Reading from XML to a Data Source

- •Creating the SpyMaster Database

- •Building the Main Form

- •Editing the Assignments

- •Editing the Specialties

- •Viewing the Agents

- •Editing the Agent Data

- •Summary

- •List of Figures

- •List of Tables

- •List of Sidebars

private void mnuFr1_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e) { lblNumber.Text = "un";

}

private void mnuFr2_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e) { lblNumber.Text = "deux";

}

private void mnuFr3_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e) { lblNumber.Text = "trois";

}

private void mnuExit_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e) { Application.Exit();

} // end setupMenu

Using Dialog Boxes to Enhance Your Programs

As programmers started developing GUI software, it quickly became apparent that certain kinds of complex tasks are needed again and again. For example, allowing the user to choose a file is a potentially risky operation because the programmer doesn’t know anything about the user’s file structure (how many drives are on the computer, what the drive names are, and so on). Also, allowing the user to type in a file name is simple to program but leads to many errors. Soon standards began to appear. If you think about most programs you use, a standard form appears when you start to save or load a program. This form takes control of the program until the user makes a choice. Forms like this are called dialog boxes because they facilitate a dialog with the user. As a user, the dialog box that appears when you save or load files seems to be much the same no matter what program you are using. This leads to shorter learning time (because the dialog box is already familiar to you) and fewer mistakes (because you already know how to get around in the dialog box). In the early days of GUI programming, developers had to be able to build file dialog boxes by hand. The same thing was true of color−choosing dialogs, print dialogs, and font selection dialogs. These dialog boxes were tedious to create by hand, and ensuring that they work exactly as users expect was challenging.

Fortunately, the .NET framework offers prebuilt, standard dialog boxes to help you include the more common dialogs used by programmers. Each of these dialogs is a class with properties, methods, and events. You can use the dialogs to greatly simplify your interactions with the user.

Exploring the Dialog Demo Program

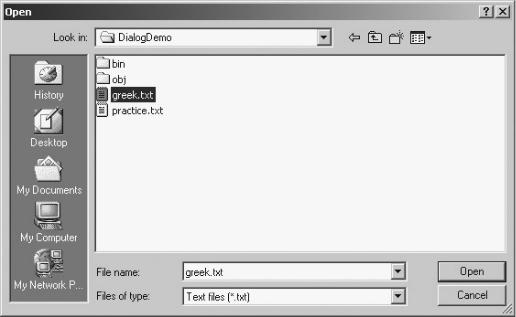

The Dialog Demo program extends the text editor built in the File IO program. It replaces the command buttons with menus and adds access to several standard dialog boxes to change the program's appearance and behavior. Figure 9.14 shows the Dialog Demo.

250

Figure 9.14: When the user chooses Open from the File menu, a familiar−looking dialog appears. The file dialog makes your job as a programmer much easier because you don’t have to worry much about how it works (isn’t encapsulation grand?). All you have to do is drop it on the form, set a few properties, and respond to its events.

Notice that the dialog box is preset to display only text files (the file names end with .txt). You can set up a filter to display any kind of file you want. You can also determine a default directory, a default file name, and other interesting characteristics.

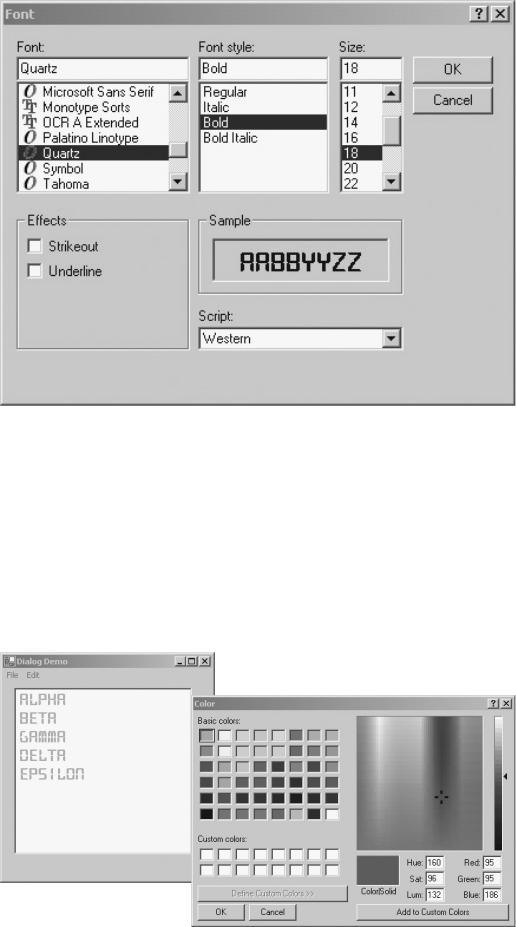

You can also change the font visible in the text editor with another custom editor. Figure 9.15 shows the font dialog.

251

Figure 9.15: The font dialog allows the user to set the font, including typeface, size, and style.

The font dialog is an especially welcome tool because fonts have a long history of causing trouble for programmers. Each user can install whatever fonts he or she wants on his own computer. However, the programmer has no way of knowing directly which fonts are on the client machines because each user’s machine has a different set of fonts installed. The font dialog sidesteps this problem by letting the user choose directly from the fonts installed on the user’s computer.

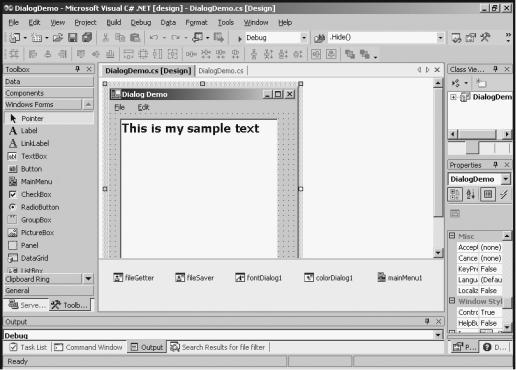

The Dialog Demo program also allows the user to change the foreground and background colors of the text editor. Figure 9.16 shows this process. Like files and fonts, color can be a challenging attribute for the programmer to control. The color dialog gives a simple mechanism for allowing the user to choose a color. The color dialog is more sophisticated than it seems at first glance. The Custom Colors option allows the user to generate a color using RGB and HSL (hue, saturation, luminance) models.

252

Figure 9.16: The user can independently set the foreground and background colors of the text editor.

Adding Standard Dialogs to Your Form

Although the standard dialogs seem to be a very diverse group of objects, they all work the same way from the programmer’s point of view. Each dialog is a control you can drop on the form. All are available in the Toolbox to the left of the IDE window. As you drop the dialogs on your form, you see them added in the off−screen space at the bottom of the form, where timers and image lists go. Like these other controls, the dialog boxes don’t have a physical presence on the screen; they appear at opportune moments under program control. Figure 9.17 shows the text editor with the dialog boxes added.

Figure 9.17: The dialogs are added to the bottom of the form. Notice the menu structure as well. Trick The dialog controls usually appear towards the bottom of the Toolbox list, so they aren’t immediately apparent in the IDE. You have to scroll down the Toolbox to see the dialog

controls.

Like any other control, a dialog has properties that affect its appearance and behavior. Also, each dialog has at least one event it can trigger. The properties and events are associated with specific types of dialogs, so they are described separately in the sections that follow.

Using the File Dialog Controls

The OpenFileDialog and SaveFileDialog controls are almost identical. It’s important to understand that the dialogs don’t actually save and load files! As a user, you expect these dialogs to save and load files, but that isn’t the case from the programmer’s point of view. The real purpose of the file dialogs is to let the user choose a file name. It’s up to the programmer to save or load the file. Although this might seem like a burden, it isn’t, because the hardest part of saving and loading files is usually getting the file name from the user. Many other tools (such as the StreamReader and StreamWriter classes you learned about earlier in this chapter) help with the actual file manipulation. Dialogs are all about communication with the user. The file dialog controls have properties that simplify and direct this communication.

253