Professional VSTO 2005 - Visual Studio 2005 Tools For Office (2006) [eng]

.pdf

Chapter 4

using System.Windows.Forms;

using Microsoft.VisualStudio.Tools.Applications.Runtime; using Word = Microsoft.Office.Interop.Word;

using Office = Microsoft.Office.Core; namespace WordEvnts

{

public partial class ThisDocument

{

private void ThisDocument_Startup(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

}

private void ThisDocument_Shutdown(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

}

#region VSTO Designer generated code

///<summary>

///Required method for Designer support - do not modify

///</summary>

private void InternalStartup()

{

this.Startup += new System.EventHandler(ThisDocument_Startup); this.Shutdown += new System.EventHandler(ThisDocument_Shutdown); this.BeforeClose += new System.ComponentModel.CancelEventHandler(ThisDocument_BeforeClose);

}

void ThisDocument_BeforeClose(object sender, System.ComponentModel.CancelEventArgs e)

{

throw new Exception(“The method or operation is not implemented.”);

}

#endregion

}

}

Listing 4-24: Event hookup code

It’s fascinating to see how simple code can have unexpected results. Inside the InternalStartup() method, you can see the Startup and Shutdown events are wired to their respective handlers. Following this pattern, we add our own event BeforeClose. Visual Studio .NET IDE magic automatically creates the handler for us and even implements a bare-bones handler complete with a single line of code that throws an exception when the document begins its closing process. However, if you accept the defaults, run the application and close the document, the application will not behave as expected.

If you expected the application to stop because an exception was thrown, you would be pleasantly surprised. The exception has already occurred but the application simply did not stop. Instead, the document closes and the exception is simply ignored. This behavior is by design. When exceptions occur, the exceptions do not interfere with the document functionality. One of the application requirements for VSTO is that the document must continue to function even in the presence of a misbehaving .NET assembly.

148

Word Automation

Printing Documents from Word

Like Microsoft Excel, print functionality is simple. Consider code that prints the current document in a Word application, shown in Listing 4-25.

Visual Basic

private sub PrintDocument() Me.PrintOut()

End Sub

C#

private void PrintDocument()

{

this.PrintOut(

ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing, ref missing);

}

Listing 4-25

From Listing 4-25, printing functionality can’t possibly get any easier than this. If you choose to call the method as presented in Listing 4-25, the application prints out the active document without any modifications, using the default settings.

The PrintOut method can print all or part of the document to include embedded shapes. The printing can occur asynchronously or the print can be customized to print completely before executing the subsequent lines of code. The Print routine can also impose page numbers on the printed document and instruct the printer to collate the document accordingly. For more fine-grained control, simply set the appropriate options of the PrintOut method.

Considerations for Word Development

The common denominator of all Microsoft Office applications is the Office COM server being targeted by the executing code. Visual Basic for Applications, unmanaged COM, and VSTO are simply different approaches to targeting the underlying server. When calls are funneled through to the Office COM server, a few things must occur before the request can be processed successfully. These initialization steps differ, depending on the programming approach used.

PIAs and RCWs for Office Word

For unmanaged COM and VBA, there is relatively little overhead. The requests are simply channeled to the COM server for processing and the results are returned. However, for the .NET approach, the CLR requires an adapter to intercept the managed call and translate it into a request that unmanaged code can understand.

The CLR uses a specially generated Runtime Callable Wrapper (RCW). This wrapper is an Interop Assembly and is used automatically for you if you have downloaded and installed the Primary Interop

149

Chapter 4

Assemblies. If you choose not to download and install the Primary Interop Assemblies, one will be created for you automatically. Once the translation occurs, the call can be funneled on to the unmanaged COM server for processing.

It is evident that this overhead causes a performance hit each time a request is made from a managed application. This overhead cannot be avoided. Once the interoperation is complete or the application has terminated, the managed resources are cleaned up automatically by the CLR. However, the CLR does not have knowledge about the unmanaged resources created to facilitate communication between the managed and unmanaged word. These resources must be cleaned up, but the CLR is unable to do so. For that reason, the .NET code must explicitly make a call to release the unmanaged resources.

Assemblies and Deployment

Another area that requires some attention is the customization assembly that runs behind the document. One common question developers have centers around associating the .NET assemblies with the Word documents. Typically, every Word document targets its own assembly. However, the .NET assembly running behind a document is not set in stone. It is both easy and relatively painless to associate a document with a different assembly or to multiple assemblies. Listing 4-26 shows some code that associates a server document with a different .NET assembly.

Visual Basic

DimservDoc as ServerDocument = new ServerDocument(“file path”) servDoc.AppManifest.Dependency.AssemblyPath = “file path”

servDoc.Save()

servDoc.Close()

C#

ServerDocument servDoc = new ServerDocument(“file path>”); servDoc.AppManifest.Dependency.AssemblyPath = “ file path “;

servDoc.Save();

servDoc.Close();

Listing 4-26: Assembly and document association

The code is fairly straightforward. First, an object of type ServerDocument is created. Next, the dependent assembly is changed to point to a new assembly given by the file path. The ServerDocument is then saved and closed. From this point onward, the ServerDocument fires the code in the new assembly. That sort of approach comes in handy in some deployment scenarios where different documents must be based on the same assembly.

Custom Actions Panes

There are several controls that aren’t covered in this book. Most of these controls are intuitive to use and require little more than a passing knowledge of their existence. However, some controls such as the task pane control require a little more thought. Microsoft Office 2003 first introduced the smart document feature. This feature allows developers to create custom document task panes that are associated with Office applications. This smart document feature has been refined to provide the customized task pane in the most recent version of VSTO.

150

Word Automation

Most developers and users are familiar with task panes, so we spare the details for another section. However, the internal plumbing deserves more attention. The task pane is a generic Windows forms control container that is able to host other controls. You may add controls to the task pane directly through code. However, the task pane is only visible in a running application if it contains controls. These controls also are not printed with the document when a print operation is requested. This makes it an excellent strategy for documents that must be generated in a print friendly manner.

The actions pane is another generic control container that sits inside the task pane control. The actions pane can be used to host other containers and controls. These controls may be wired to events as well. There are some disadvantages of actions panes that must be noted. Actions panes cannot be hidden through code and cannot be repositioned either. The reason for this is that the actions pane is embedded in the task pane. One workaround is to simply reposition the task pane.

Summar y

The VSTO Word API is surprisingly powerful yet simple to use. The available functionality spans the entire range of functionality available with Microsoft Office today. Some of the functionality is exposed through a few key objects such as the ThisApplication object. Objects such as these provide global hooks where calling code can conveniently access internal objects, data, and the document functionality of the Microsoft Office application.

The Range object is the key to most of that functionality. The Range object wraps formatting and addressing functionality behind a simple interface. In addition to the in-memory object, the Range object also presents itself as a bona fide user interface control that is fully accessible from the OfficeCodeBehind.

Another potent control makes an appearance in VSTO. The backgroundWorker control is designed to be used with Windows forms and User interface–related code. The control brings the power of threading to the design surface in a way that has never been done before. The control is not without issues.

Unfortunately, the control cannot be used in applications such as windows services. Also, there are certain restrictions on controls that are accessed from the backgroundWorker control.

.NET and VSTO have certainly made an effort to bring threading to the masses through the backgroundWorker control and the associated threading classes. It is still not a move that promotes a warm and fuzzy feeling to seasoned developers, since these implementations trivialize the complexity of these approaches. Threading issues are extremely difficult to discover and often do not surface until it is too late. Still, if you care to learn the ropes first and have the stomach for the steep learning curve, such an approach can realize a significant performance boost to your applications. However, you must proceed with every bit of caution and afford the technique the due diligence it so rightly deserves.

This chapter also covered tables in some detail. Tables are made up of rows and columns as well as functionality and formatting. Formatting can be applied through table styles. When adding styles programmatically, the table style overwrites any custom styles that are already present. If you need to maintain custom styles, add the supported style to the table object first, and then add your custom style.

Another interesting control worth noting is the actions pane. Controls embedded in the ActionsPane control do not print by default. Normally, a print operation prints the document and the embedded controls they may contain. The only way to prevent these embedded objects from printing is to set their visible property to false. The ActionsPane control neatly sidesteps this issue.

151

Outlook Automation

Four hundred million people use Microsoft Office today. It is fair to assume that most of these users do some sort of email task at some point during the day, because Microsoft Outlook is the most popular product of the Microsoft Office suite. Since Microsoft Outlook is the dominant email application for corporations, Microsoft is fairly keen on maintaining that large customer base. One key way to attract and keep customers is to improve the quality and availability of applications built on Microsoft Office technology.

VSTO brings this technology home by providing Outlook add-ins that allows applications to hook into the Microsoft Office Outlook platform. Using add-ins, it is possible to customize or improve the appearance and functionality of the standard toolbar in an Outlook application.

This chapter will focus on programming tasks associated with Microsoft Outlook. The approach is somewhat different because Outlook automation is achieved through the use of add-ins. The code that you write to implement programming requirements is compiled into a .NET managed assembly. This assembly is loaded as a managed add-in into Microsoft Outlook when the Outlook application first initializes. From this point, your code is executed in response to Outlook events.

Add-ins created this way are global in nature and are used continually unless unloaded by the user or through an unhandled exception.

Notice that this is different from an Excel spreadsheet application. Excel applications are based on a set of templates that provide functionality to the Excel object, and the templates are not global in scope. In any case, the material here will focus on developing add-ins. In addition, the code will show you how to target the event model of Outlook because add-ins typically respond to events raised by the Outlook Object Model (OOM). For instance, your code may take some action based on new email notifications.

A large majority of the chapter is dedicated to manipulating emails messages, updating address books, managing contacts, scheduling meetings, and implementing calendar functionality. These approaches are all presented from a data-driven perspective. For instance, a new email in the Inbox triggers a new email event notification. The event fires code in your custom add-in that examines the data present in the email. Based on the contents of that data, some action is performed.

Chapter 5

We will also examine the key objects responsible for driving the user interface functionality. It’s important to understand the relationships among these intrinsic objects if you intend to customize the user interface. One key object in the Outlook namespace is the MAPI object. We reserve a more detailed examination of Messaging Application Programming Interface (MAPI) for later but for now, you should note that MAPI is the glue that holds the Outlook application together.

Finally, we spend some time examining the updated security model. The improvement to the security model helps mitigate the risk of malware that may be spread through Outlook emails. Email integration and connectivity has also been enhanced. Code can now take advantage of new email objects and events that improve the programming experience for Outlook developers.

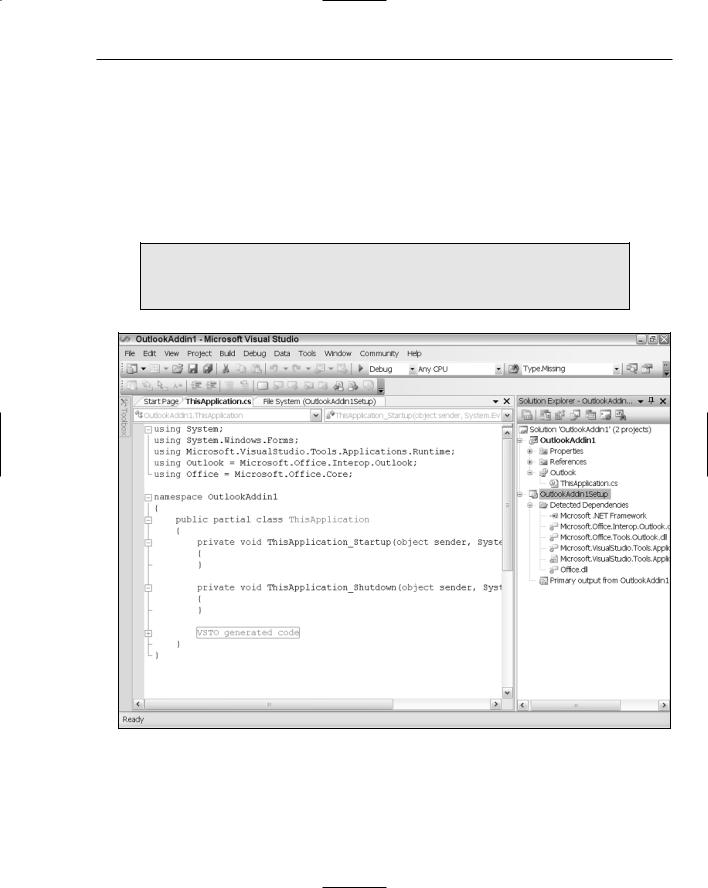

Configuring VSTO Outlook

VSTO ships with a Microsoft Outlook add-in loader component that allows managed code to use managed as well as unmanaged add-ins. To begin writing code that targets Microsoft Outlook, you will first need to configure Visual Studio. The installation instructions are provided in Chapter 1. From this point, the Microsoft Outlook add-in should appear in the Visual Studio IDE task pane, as shown in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1

You should notice that there are no template options for Microsoft Outlook. The reason for this absence is that Microsoft Outlook is an email application. On the other hand, template-based projects such as Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Word are applications that are centered on document creation and manipulation. Templates are provided in these environments to ease the document creation process.

154

Outlook Automation

If you select the Outlook add-in option and create a new project, the Visual Studio IDE opens up to the OfficeCodeBehind file, as shown in Figure 5-2.

Notice also that Visual Studio has added a setup project in the property pages. This project contains all the dependent assemblies that your application will require to function correctly. Also, a new primary output subfolder is available, with a few configurable properties. These properties allow the developer to customize the installer package to ease the burden of installation and deployment. For instance,

the new option allows you to detect new installation versions automatically through the detectnew installation property. To see the list of available configuration properties, right-click the Outlook setup node in the property pages hierarchy tree and choose Properties.

During application development, it is often necessary to purge the Outlook add-ins that are loaded because these add-ins can significantly slow down the Outlook initialization process.

Figure 5-2

155

Chapter 5

Press F5 to run the application without making any changes to OfficeCodeBehind. If you haven’t configured Microsoft Outlook, the configuration appears. You may use it to configure or add the address to the Microsoft Exchange server. If you do not know the address of the Microsoft Exchange server, ask your network administrator. If Microsoft Exchange server is already configured, simply accept the defaults and proceed.

After configuration is complete, Microsoft Outlook 2003 will be launched, as shown in Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3

Microsoft Outlook defines certain internal objects that represent user interfaces in Outlook that you need to be familiar with in order to build robust, perfomant add-ins. For instance, the toolbar collection displays the standard toolbar buttons that are part of every component in the Microsoft Office VSTO suite. You can use the code you saw in Chapter 2 and Chapter 4 to customize the toolbar for Microsoft Outlook. Although Outlook differs from Excel and Word applications, the approach to programming the toolbars and the menus in VSTO remains consistent across each component.

Another example of an important object is the Advanced Find dialog that is used for searching. The dialog is generated from an Outlook Inspector object. Most toolbar functionality events will launch the Inspector object that, in turn, generates an Inspector dialog. A more detailed discussion of Inspector objects follow in the next section.

When Microsoft Outlook first launches as in Figure 5-4, an Explorer object creates the initial Outlook view. The view may be divided into one or more panes, depending on the end-user configuration. Explorer objects are also generated when the user selects File New from the Outlook menu bar.

156

Outlook Automation

Key Outlook Objects

The Outlook API is spread wide. However, most of the functionality is contained within a few central objects. Once you are familiar with these objects, it’s easy to customize Outlook. Before we dive into the objects, it is helpful to gain some perspective on the underlying protocol that Microsoft Outlook uses for email communication. An appreciation of the technology can go a long way when new features, such as extended email management or custom user forms, need to be implemented on top of the Microsoft Outlook platform. Custom user forms are presented later in the chapter.

What Is MAPI?

Messaging Application Programming Interface (MAPI) is not an object. Rather, it is a protocol that allows different Windows-based applications to interact with email applications. MAPI is platform neutral and can facilitate data exchange across multiple systems. MAPI was originally designed and built by Microsoft and has gone through several revisions. There are other protocols for messaging that are equally popular, such as Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) and Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP). However, these protocols are not covered in this book.

MAPI brings certain advantages to the table. For instance, MAPI allows you to manipulate views. MAPI allows you to add custom features to the options menu in Outlook. MAPI also provides performance improvements as compared to implementations that run without MAPI. This is certainly not an exhaustive list, but it is sufficient to provide you with a general idea of MAPI’s effectiveness as a protocol.

The data contained in Outlook is organized into Outlook folders. MAPI provides access to the data stored in these folder structures through the Application object. The actual data for Microsoft Outlook is stored in files with a .pst extension for accounts configured without Microsoft Exchange. Accounts configured with Microsoft Exchange store files with an .ost extension. MAPI simply provides a way to access this data through a valid session. Listing 5-1 provides an example.

Visual Basic

If Me.Session.Folders.Count > 0 Then

Dim folder As Outlook.MAPIFolder = Me.Session.Folders(1) If Not folder Is Nothing Then

MessageBox.Show(“The “ & folder.Name & “ folder contains “ & folder.Items.Count & “ items.”)

End If End If

C#

if (this.Session.Folders.Count > 0)

{

Outlook.MAPIFolder folder = this.Session.Folders[1];

{

MessageBox.Show(“The “ + folder.Name + “ folder contains “ + folder.Items.Count + “ items.”);

}

}

Listing 5-1: MAPI folder manipulation

157