Professional Visual Studio 2005 (2006) [eng]

.pdf

Chapter 43

Selecting the DeviceApplication1 node brings up additional information about the project in the properties grid. This includes the version of the .NET Framework and platform for which this project is being written.

Design Skin

One of the significant improvements in Visual Studio 2005 is the inclusion of design skins for device applications. In the past, developers building forms for devices used the standard form designer to lay out controls, which approximated what the form would look like when it was run on the device. In most cases this layout had to be tweaked, and in some cases redesigned, to fit the target device. Figure 43-3 shows two forms: Form1 with the design skin turned on, and Form2 with the design skin turned off.

Figure 43-3

The design skin can be toggled on and off using the right-click context menu off the form design surface. You might be wondering why you would want to turn off the design skin. Other than giving you a better illustration of what the form is going to look like, the design skin does not add very much functionality. It also adds overhead every time the form is rendered in the designer. As such, Visual Studio 2005 is more responsive with the design skin disabled. Although the examples in this chapter show the design skin, there is no reason why you can’t work with the design skin disabled.

Orientation

Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition added the capability to change the orientation on a Pocket PC from portrait to landscape. Support has been added to Visual Studio 2005 to switch the orientation of the

596

Building Device Applications

design surface. This automatically resizes the form to the appropriate dimensions, enabling you to validate that all of your controls are correctly positioned for both orientations.

To alter the orientation of the design surface you can select Rotate Left or Rotate Right from the rightclick context menu off the design surface. If you have the design skin enabled, it will be rotated in the direction specified, while the form you are working on will remain upright. Without the design skin, the form will be resized as if the skin were present so you can still see the effect on your visual layout.

Buttons

The one bit of functionality that the design skin does add is the capability to automatically generate a code stub for handling hardware button events. As you move your mouse over the hardware buttons on the design skin, a tooltip appears, letting you know which button it is (such as Soft Key 1). Clicking on a button takes you to an event handler for the KeyDown event of the Form shown in the following code snippet:

Public Class Form1

Private Sub Form1_KeyDown(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As KeyEventArgs)_ Handles MyBase.KeyDown

If (e.KeyCode = System.Windows.Forms.Keys.Up) Then ‘Rocker Up

‘Up End If

If (e.KeyCode = System.Windows.Forms.Keys.Down) Then ‘Rocker Down

‘Down End If

If (e.KeyCode = System.Windows.Forms.Keys.Left) Then

‘Left

End If

If (e.KeyCode = System.Windows.Forms.Keys.Right) Then

‘Right

End If

If (e.KeyCode = System.Windows.Forms.Keys.Enter) Then

‘Enter

End If

End Sub

End Class

Note a few important points in this code snippet. First, the event handler actually handles the KeyDown event of the form. Because the keys may have different functionality depending on which form of your application is open, it makes sense for them to map to the form. Second, note that this event handler only handles the directional keys, the rocker, and the Enter key.

Most devices have a number of additional hardware buttons, referred to as application keys. These keys do not have a set function and can appear anywhere (if at all) on the device. Unfortunately, there is no automatic mapping to the form events for any of the application keys, although use of the Hardware Button control (which provides this functionality) is covered later in this chapter.

The last point to take away from this snippet is that it is generated code, and you should probably replace the entire contents of the event handler with your own code that uses a more efficient syntax, such as a SELECT statement.

597

Chapter 43

Toolbox

Device applications have their own set of tabs within the Toolbox window. These are essentially the same as the tabs shown for building normal applications except that they are prefixed with the word “Device.” Any developer who has worked with controls for a Windows application will feel at home using the device controls. Some controls are specific to device applications and enable you to take advantage of some of the device-specific functionality.

Common Controls

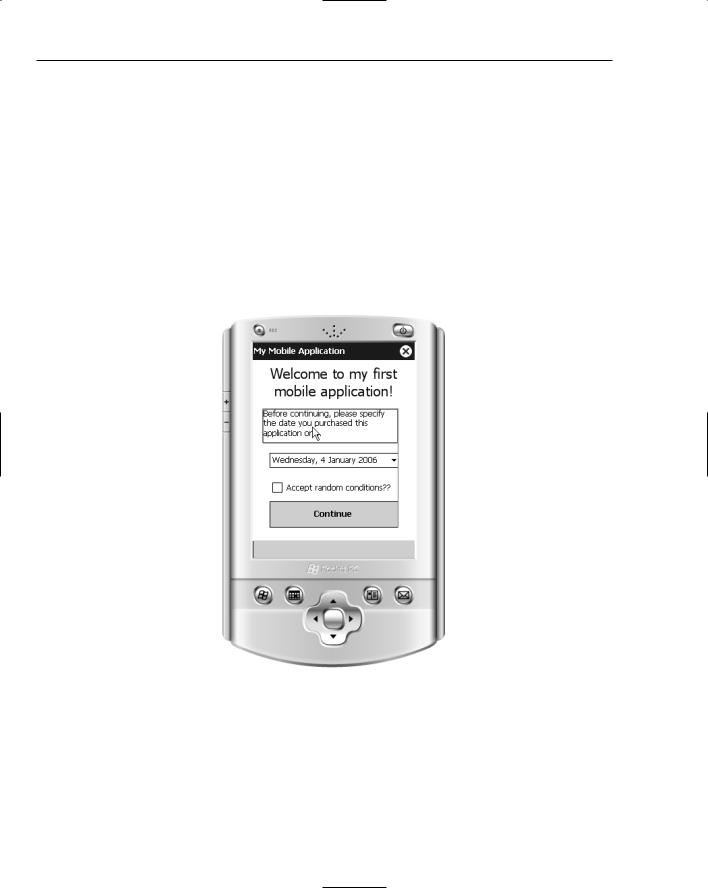

The standard controls such as textboxes, checkboxes, labels, and buttons are all available from the Common Device Controls tab. Figure 43-4 illustrates a simple form with a number of controls visible. Note that device developers benefit from the same set of designer features as Windows developers. These include the alignment guides, as shown in Figure 43-4.

Figure 43-4

The first version of the .NET Compact Framework was missing not only several of the standard controls, such as a DateTimePicker, but also basic layout functionality such as anchoring and docking. Version 2.0 of the .NET Compact Framework supports a wide range of controls, including splitters and status bars, as well as anchoring, docking, and auto-scrolling for panels and forms.

598

Building Device Applications

Mobile Controls

When building device applications, it is important to design them with the user interface in mind. Simply taking an existing Windows application and rebuilding it for the device is unlikely to work. The best device applications not only have intuitive form designs, they also make use of the available devicespecific functionality, including the hardware buttons, the input panel, and the notification bubble.

Hardware Button

The discussion of the design skin noted that although the form KeyDown event handler could be used to trap some of the hardware buttons, it doesn’t trap application key events. To handle one or more application keys, you need to add a HardwareButton control to the form. This control does not have a visual component, so it appears in the nonvisual area of the designer.

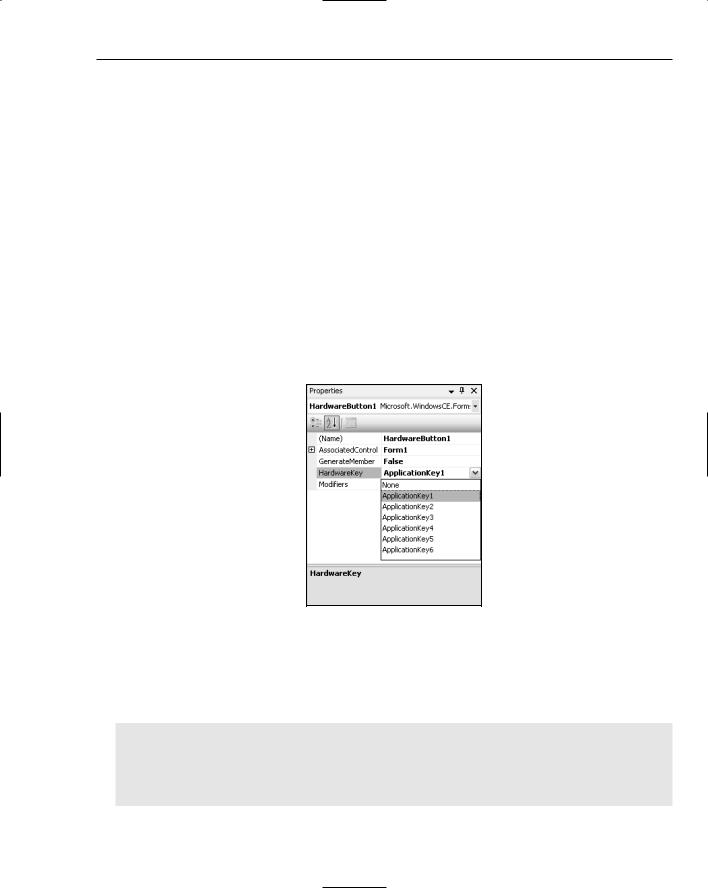

Figure 43-5 shows the associated properties for a HardwareButton control that has been added to Form1. The HardwareButton redirects the hardware button events to an AssociatedControl. The

AssociatedControl must be a Form, Panel, or CustomControl; otherwise, a NotSupportedException will be raised when the application is run. Any of the six application keys can be selected as the Hardware Key. Unfortunately, these are not flags, so they cannot be concatenated to allow a single HardwareButton to wire up all of the application keys.

Figure 43-5

Once the HardwareButton control has been added to the form and the appropriate properties set, you still need to handle the click events. This can be done using an event handler for either the KeyPress or KeyUp event for the AssociatedControl. For example, if you were to use Form1 as the Associated Control, the event handler might look like the following:

Private Sub Form1_KeyUp(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As KeyEventArgs) _ Handles MyBase.KeyUp

If e.KeyCode = Microsoft.WindowsCE.Forms.HardwareKeys.ApplicationKey1 Then

MsgBox(“Hardware Key event”)

End If

End Sub

599

Chapter 43

Input Panel

Most device applications require some form of text input, and this is usually done through the Soft Input Panel, or SIP, as it is more commonly known. The SIP is a visual keyboard that can be used to tap out words. Alternative input methods such as the Letter Recognizer use the same input panel for text entry. Figure 43-6 shows an emulator for a Pocket PC 2003 Second Edition device with the SIP showing. In this case, the SIP is displaying the keyboard.

Figure 43-6

The SIP takes up valuable screen real estate when it is both open (as in Figure 43-6) and closed (only the bottom bar is visible). As such, it should only be added to a form when required. However, the default behavior when a menu is added to the form is for the SIP to become visible, allowing it to be opened and closed at will. Hence, it is important to be able to control what happens when the SIP changes status.

The first step in working with the SIP is to add an InputPanel control to the form. Again, this control appears in the nonvisual area of the form designer and has a single property, Enabled, which determines whether the SIP is open or closed. This control also exposes an EnabledChanged event, which is raised when the status of the SIP changes.

Double-clicking on the newly created InputPanel generates an event handler for the EnabledChanged event. This handler needs to reposition the controls to optimize the layout for the reduced real estate.

600

Building Device Applications

Because the InputPanel appears as if it were a control that sits on top of the form, when it changes state it does not resize the form. This means that there is no resize event on the form, so any repositioning of controls needs to be done via the EnabledChanged event handler.

At this stage, it is worth noting that the standard controls all support anchoring and docking. On applications designed for a desktop computer, these layout options make sense. However, on a mobile device, where screen real estate is already limited, allowing the controls to automatically resize often results in a clunky and difficult to use interface. For example, take a simple screen layout that contains a client list and two buttons. If the device is in portrait mode the list should be positioned above the two buttons so the maximum number of items can be displayed. However, in landscape mode, instead of repositioning the controls so the list takes the full width of the device, the list should be repositioned alongside the two buttons.

This could be achieved by defining multiple screen layouts based on the size and orientation of the screen. The following code snippet shows how a number of screen layouts can be toggled between depending on the screen orientation:

Public Class Form1

<Flags()> _

Private Enum FormLayout SIP_Open SIP_Closed Portrait

Landscape End Enum

Private Sub Form1_Resize(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As System.EventArgs) Handles MyBase.Resize

Layout() End Sub

Private Sub InputPanel1_EnabledChanged(ByVal sender As System.Object, ByVal e As System.EventArgs) Handles InputPanel1.EnabledChanged

Layout()

End Sub

Private Function DetermineCurrentLayout() As FormLayout

Dim currentLayout As FormLayout

‘Determine whether it is landscape or portrait

If Me.Width > Me.Height Then

currentLayout = FormLayout.Landscape

Else

currentLayout = FormLayout.Portrait

End If

‘Determine whether the SIP is Open or Closed If Me.InputPanel1.Enabled Then

currentLayout = currentLayout Or FormLayout.SIP_Open

Else

currentLayout = currentLayout Or FormLayout.SIP_Closed End If

Return currentLayout

601

Chapter 43

End Function

Private Sub Layout()

Dim newLayout As FormLayout = DetermineCurrentLayout()

Select Case newLayout

Case FormLayout.Portrait Or FormLayout.SIP_Open

Layout_PortraitWithInput()

Case FormLayout.Portrait Or FormLayout.SIP_Closed

Layout_PortraitWithOutInput()

Case FormLayout.Landscape Or FormLayout.SIP_Open

Layout_LandscapeWithInput()

Case FormLayout.Landscape Or FormLayout.SIP_Closed

Layout_LandscapeWithOutInput()

End Select

End Sub

Private Sub Layout_PortraitWithOutInput()

‘Position list control above the two buttons

End Sub

Private Sub Layout_PortraitWithInput() ‘Position list control above the two buttons

‘Reduce the height of the list and move the buttons up ‘ so that they are both visible above the SIP

End Sub

Private Sub Layout_LandscapeWithOutInput()

‘Position list control along side the two buttons

End Sub

Private Sub Layout_LandscapeWithInput()

‘Position list control along side the two buttons ‘Reduce the height of the list control so that all ‘ items are visible above the SIP

End Sub

End Class

This code snippet defines an enumeration that can be used to specify the current screen orientation. Two factors warrant consideration: the orientation of the screen and whether the SIP is visible. It may be that other form factors, such as a square screen, could be added to this list.

When an event is triggered that alters the orientation of the screen (such as the form resize event) or the status of the SIP (such as the InputPanel EnabledChanged event), the new screen configuration is detected using the DetermineCurrentLayout method, and the contents of the form are rearranged.

Notification

There are times when a background application might want to notify a user about a particular event, or get user feedback without bringing the application to the foreground. This can be done with a Notification bubble. The contents of the bubble are essentially an HTML document that can use form input controls such as textboxes and buttons to retrieve user input.

602

Building Device Applications

Similar to both the HardwareButton and the InputPanel, when a Notification control is added to the form it appears in the nonvisual section of the designer. A number of properties can be set on a Notification control that determine the caption, icon, and text of the notification. There is also a Critical property, which can be set to heighten the importance of the notification, and an Initial Duration property, which controls how long the notification is shown. The Text property is where the HTML content is added to the notification bubble. While it is possible to use the property grid to enter this property, you will likely need to dynamically build the HTML content based on the status of your application. The following code snippet creates and displays the notification bubble illustrated in Figure 43-7:

Private Sub NotifyUser()

‘Build the HTML content for the Notification Bubble Dim htmlContent As System.Text.StringBuilder

htmlContent = New System.Text.StringBuilder(“<html><body>”) htmlContent.Append(“<a href=””Reference.htm””>Test Link</a>”) htmlContent.Append(“<p><form method=””GET”” action=mybubble>”) htmlContent.Append(“<p>This is an <font color=””#0000FF””><b>HTML</b></font>”) htmlContent.Append(“notification stored in a <font color=””#FF0000””>”) htmlContent.Append(“<i>string</i></font> table!</p>”) htmlContent.Append(“<p><input type=text name=textinput “) htmlContent.Append(“value=””Input Sample””><input type=’submit’></p>”) htmlContent.Append(“<p align=right><input type=button name=OK value=’Ok’>”)

htmlContent.Append(“<input type=button name=’cmd:2’ value=’Cancel’></p>”) htmlContent.Append(“</body></html>”)

‘Set the Notification content Notification1.Text = htmlContent.ToString

‘Set the title and make this a critical bubble (red border) Notification1.Caption = “Title”

Notification1.Critical = True

‘Display the Notification bubble Notification1.Visible = True

End Sub

In addition to building the HTML content for the notification bubble, this code also sets the Caption, or title, for the bubble, makes it Critical, which will make the border appear red, and finally displays the bubble. Instead of the more common Show method that is used for forms, to display the notification bubble, set the Visible property to True. In Figure 43-7 you can see that the notification bubble is made up of three distinct parts. The icon is placed in the main menu bar at the top of the screen, and this icon remains visible until the user dismisses the bubble. Below the icon, the bubble expands to include a title bar and the main notification window, where the HTML controls are displayed.

Double-clicking the Notification control attaches an event handler to the ResponseSubmitted event. This is one of two key events raised by the Notification control, and is raised whenever a user dismisses the notification bubble. To dismiss a notification bubble, there must be at least one control, such as a hyperlink or a button, that can submit information. Failing to include one of these controls results in users being unable to get rid of the notification bubble.

603

Chapter 43

Figure 43-7

The event handler for the ResponseSubmitted event has a ResponseSubmittedEventArgs type as a parameter. This class has a single String property, which is the Response. The contents of this string will vary depending on the type of response given. In this example, three types of responses might be received from the user:

Clicking Test Link would have set the response string equal to the URL specified for the link. In this case, the URL was Reference.htm. It is up to the application how this is processed, as it does not automatically navigate to this URL.

The Submit button is actually a form Input control of type Submit, and as such submits the data collected by the form. In this case, you have a text box, so the response would appear as follows:

mybubble?textinput=Input+Sample

Notice that the name of the form being submitted is at the beginning of the string, and then all input controls are appended after the question mark in a name=value pattern. This pattern is useful when parsing the response string for form data.

The last form of response is the value of any form button. In this case, clicking OK would generate a response equal to the value property of the button, which would be Ok.

604

Building Device Applications

One other action can be performed on the form, which is to click the Cancel button. Clicking this button does not raise the ResponseSubmitted event, but instead minimizes the notification bubble so only the icon appears in the menu bar. What makes this button special is the use of cmd:2 as the name of the button. This is actually a non-documented feature, but you can use cmd:0–4 as identifiers for buttons for which you want to simply close the bubble and not send a response.

The other event is the BubbleChanged event, which is triggered when the visibility of the notification bubble changes. In most cases the application will have displayed the bubble and will receive notification when the bubble is dismissed, via the ResponseSubmitted event. On some occasions, however, a user is not quick enough to interact with the notification, or perhaps chooses to ignore it. Once the InitialDuration has expired, the notification bubble automatically hides itself. In this case, it is important for the application to be notified when the visibility of the bubble changes, because a timer may need to be started to re-prompt the user.

Debugging

In the past, writing applications for mobile devices was a time-consuming process. The release of the Compact Framework brought with it a new wave of interactive debugger support for building device applications. Now developers wanting to build mobile applications have the same support for debugging applications as they do for desktop or web applications. Subsequent chapters in this book cover the new debugging features within Visual Studio 2005. Most of these apply equally to debugging device applications. This section examines how you can use either an emulator or a real device to debug your application.

Emulator

Although mobile devices have decreased in price considerably over the last year or so, they are still an expensive investment for a developer to make. This is especially true given the speed at which devices change and become obsolete. As such, it became evident that if there were to be more mobile developers, they would need to be able to build and test their applications without having to purchase real devices. Device emulators are important because they provide a low-cost alternative for developers.

While emulators are a good alternative, they are not a complete substitute for the real thing. It is always preferable to know and have access to the device that will be used to run the application. However, this is not always an option, and definitely not a requirement for building mobile applications.

Visual Studio 2005 ships with a number of emulators, varying in size and resolution, for the Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition (Pocket PC and Smartphone) and Windows CE 5.0. This enables developers to test their application on a variety of different form factor devices. The emulators also come with builtin virtual radio antennas so that phone and SMS activity can be simulated.

The first time you run your mobile application, Visual Studio 2005 prompts you to specify a device to deploy to. This list will display both physical devices and emulators that are compatible with your current project type. Figure 43-8 illustrates this dialog for a Pocket PC application. You can use the checkbox to suppress this dialog to improve the rate at which you can build and test your application. The dialog can be re-enabled via the Device Tools node on the Options window, accessible from the Tools menu.

605