Pro CSharp And The .NET 2.0 Platform (2005) [eng]

.pdf

914 CHAPTER 24 ■ ASP.NET 2.0 WEB APPLICATIONS

<trace

enabled="true"

requestLimit="10"

pageOutput="false"

traceMode="SortByTime"

localOnly="true"

/>

Customizing Error Output via <customErrors>

The <customErrors> element can be used to automatically redirect all errors to a custom set of *.htm files. This can be helpful if you wish to build a more user-friendly error page than the default supplied by the CLR. In its skeletal form, the <customErrors> element looks like the following:

<customErrors defaultRedirect="url" mode="On|Off|RemoteOnly"> <error statusCode="statuscode" redirect="url"/>

</customErrors>

To illustrate the usefulness of the <customErrors> element, assume your ASP.NET web application has two *.htm files. The first file (genericError.htm) functions as a catchall error page. Perhaps this page contains an image of your company logo, a link to e-mail the system administrator, and some sort of apologetic verbiage. The second file (Error404.htm) is a custom error page that should only occur when the runtime detects error number 404 (the dreaded “resource not found” error). Now, if you want to ensure that all errors are handled by these custom pages, you can update your Web.config file as follows:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<configuration xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/.NetConfiguration/v2.0"> <appSettings/>

<connectionStrings/>

<system.web>

<compilation debug="false"/> <authentication mode="Windows"/>

<customErrors defaultRedirect = "genericError.htm" mode="On"> <error statusCode="404" redirect="Error404.htm"/>

</customErrors>

</system.web>

</configuration>

Note how the root <customErrors> element is used to specify the name of the generic page for all unhandled errors. One attribute that may appear in the opening tag is mode. The default setting is RemoteOnly, which instructs the runtime not to display custom error pages if the HTTP request came from the same machine as the web server (this is quite helpful for developers, who would like to see the details). When you set the mode attribute to “on,” this will cause custom errors to be seen from all machines (including your development box). Also note that the <customErrors> element may support any number of nested <error> elements to specify which page will be used to handle specific error codes.

To test these custom error redirects, build an *.aspx page that defines two Button widgets, and handle their Click events as follows:

private void btnGeneralError_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

// This will trigger a general error. throw new Exception("General error...");

}

private void btn404Error_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

CHAPTER 24 ■ ASP.NET 2.0 WEB APPLICATIONS |

915 |

// This will trigger 404 (assuming there is no file named MyPage.aspx!)

Response.Redirect("MyPage.aspx");

}

Options for Storing State via <sessionState>

Far and away the most powerful aspect of a Web.config file is the <sessionState> element. By default, ASP.NET will store session state using an in-process *.dll hosted by the ASP.NET worker process (aspnet_wp.exe). Like any *.dll, the plus side is that access to the information is as fast as possible. However, the downside is that if this AppDomain crashes (for whatever reason), all of the user’s state data is destroyed. Furthermore, when you store state data as an in-process *.dll, you cannot interact with a networked web farm. By default, the <sessionState> element of your Web.config file looks like this:

<sessionState

mode="InProc"

stateConnectionString="tcpip=127.0.0.1:42424" sqlConnectionString="data source=127.0.0.1;Trusted_Connection=yes" cookieless="false"

timeout="20"

/>

This default mode of storage works just fine if your web application is hosted by a single web server. However, under ASP.NET, you can instruct the runtime to host the session state *.dll in

a surrogate process named the ASP.NET session state server (aspnet_state.exe). When you do so, you are able to offload the *.dll from aspnet_wp.exe into a unique *.exe. The first step in doing so is to start the aspnet_state.exe Windows service. To do so at the command line, simply type

net start aspnet_state

Alternatively, you can start aspnet_state.exe using the Services applet accessed from the Administrative Tools folder of the Control Panel (see Figure 24-10).

Figure 24-10. The Services applet

The key benefit of this approach is that you can configure aspnet_state.exe to start automatically when the machine boots up using the Properties window. In any case, once the session state server is running, alter the <sessionState> element of your Web.config file as follows:

916 CHAPTER 24 ■ ASP.NET 2.0 WEB APPLICATIONS

<sessionState

mode="StateServer"

stateConnectionString="tcpip=127.0.0.1:42424" sqlConnectionString="data source=127.0.0.1;Trusted_Connection=yes" cookieless="false"

timeout="20"

/>

Here, the mode attribute has been set to StateServer. That’s it! At this point, the CLR will host session-centric data within aspnet_state.exe. In this way, if the AppDomain hosting the web application crashes, the session data is preserved. Also notice that the <sessionState> element can also support a stateConnectionString attribute. The default TCP/IP address value (127.0.0.1) points to the local machine. If you would rather have the .NET runtime use the aspnet_state.exe service located on another networked machine (again, think web farms), you are free to update this value.

Finally, if you require the highest degree of isolation and durability for your web application, you may choose to have the runtime store all your session state data within Microsoft SQL Server. The appropriate update to the Web.config file is simple:

<sessionState

mode="SQLServer"

stateConnectionString="tcpip=127.0.0.1:42424" sqlConnectionString="data source=127.0.0.1;Trusted_Connection=yes" cookieless="false"

timeout="20"

/>

However, before you attempt to run the associated web application, you need to ensure that the target machine (specified by the sqlConnectionString attribute) has been properly configured. When you install the .NET Framework 2.0 SDK (or Visual Studio 2005), you will be provided with two files named InstallSqlState.sql and UninstallSqlState.sql, located by default under <%windir%>\Microsoft.NET\Framework\<version>. On the target machine, you must run the InstallSqlState.sql file using a tool such as the SQL Server Query Analyzer (which ships with Microsoft SQL Server).

Once this SQL script has executed, you will find a new SQL Server database has been created (ASPState) and that contains a number of stored procedures called by the ASP.NET runtime and

a set of tables used to store the session data itself (also, the tempdb database has been updated with a set of tables for swapping purposes). As you would guess, configuring your web application to store session data within SQL Server is the slowest of all possible options. The benefit is that user data is as durable as possible (even if the web server is rebooted).

■Note If you make use of the ASP.NET session state server or SQL Server to store your session data, you must make sure that any custom types placed in the HttpSessionState object have been marked with the

[Serializable] attribute.

The ASP.NET 2.0 Site Administration Utility

To finish up this section of the chapter, I’d like to mention the fact that ASP.NET 2.0 now provides a web-based configuration utility that will manage many settings within your site’s Web.config file. To activate this utility (see Figure 24-11), select the WebSite ASP.NET Configuration menu option of Visual Studio 2005.

CHAPTER 24 ■ ASP.NET 2.0 WEB APPLICATIONS |

917 |

Figure 24-11. The ASP.NET 2.0 site administration utility

Most of this tool’s functionality is used to establish security-centric details of your site (authentication mode, user roles, security providers, etc.). In addition, however, this tool allows you to establish application settings, debugging details, and error pages.

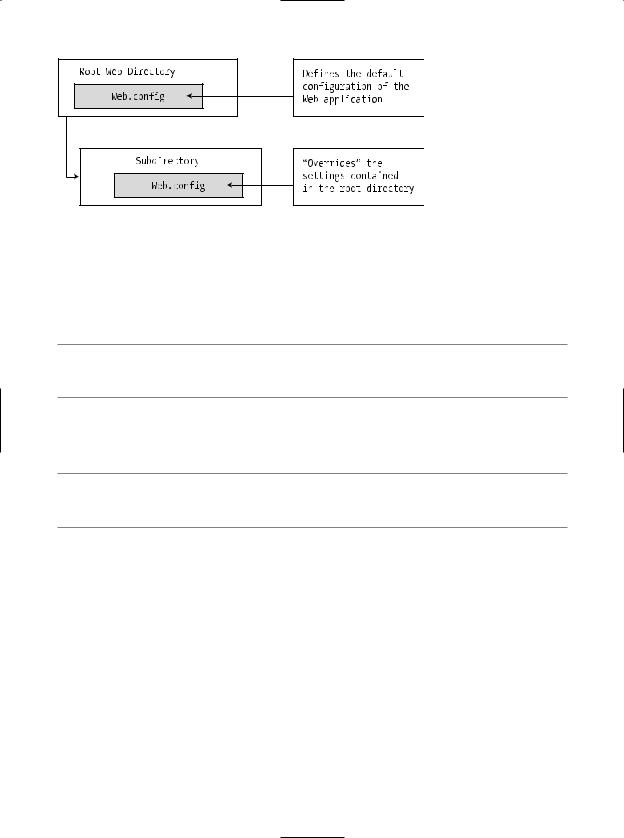

Configuration Inheritance

Last but not least is configuration inheritance. As you learned in the previous chapter, a web application can be defined as the set of all files contained within a root directory and any optional subdirectories. All the example applications in this and the previous chapter have existed on a single root directory managed by IIS (with the optional Bin folder). However, large-scale web applications tend to define numerous subdirectories off the root, each of which contains some set of related files. Like a traditional desktop application, this is typically done for the benefit of us mere humans, as a hierarchal structure can make a massive set of files more understandable.

When you have an ASP.NET web application that consists of optional subdirectories off the root, you may be surprised to discover that each subdirectory may have its own Web.config file! By doing so, you allow each subdirectory to override the settings of a parent directory. If the subdirectory in question does not supply a custom Web.config file, it will inherit the settings of the next available Web.config file up the directory structure. Thus, as bizarre as it sounds, it is possible to inject an OO look and feel to a raw directory structure. Figure 24-12 illustrates the concept.

918 CHAPTER 24 ■ ASP.NET 2.0 WEB APPLICATIONS

Figure 24-12. Configuration inheritance

Of course, although ASP.NET does allow you to define numerous Web.config files for a single web application, you are not required to do so. In a great many cases, your web applications function just fine using nothing else than the Web.config file located in the root directory of the IIS virtual directory.

■Note Recall from Chapter 11 that the machine.config file defines numerous machine-wide settings, many of which are ASP.NET-centric. This file is the ultimate parent in the configuration inheritance hierarchy.

That wraps up our examination of ASP.NET. As mentioned in Chapter 23, complete and total coverage of ASP.NET 2.0 would require an entire book on its own. In any case, I do hope you feel comfortable with the basics of the programming model.

■Note If you require an advanced treatment of ASP.NET 2.0, check out Expert ASP.NET 2.0 Advanced Application Development by Dominic Selly et al. (Apress, 2005).

To wrap up our voyage, the final chapter examines the topic of building XML web services under .NET 2.0.

Summary

In this chapter, you rounded out your knowledge of ASP.NET by examining how to leverage the HttpApplication type. As you have seen, this type provides a number of default event handlers that allow you to intercept various applicationand session-level events.

The bulk of this chapter was spent examining a number of state management techniques. Recall that view state is used to automatically repopulate the values of HTML widgets between postbacks to a specific page. Next, you checked out the distinction of applicationand session-level data, cookie management, and the ASP.NET application cache. Finally, you examined a number of elements that may be contained in the Web.config file.

CHAPTER 25 ■ UNDERSTANDING XML WEB SERVICES |

921 |

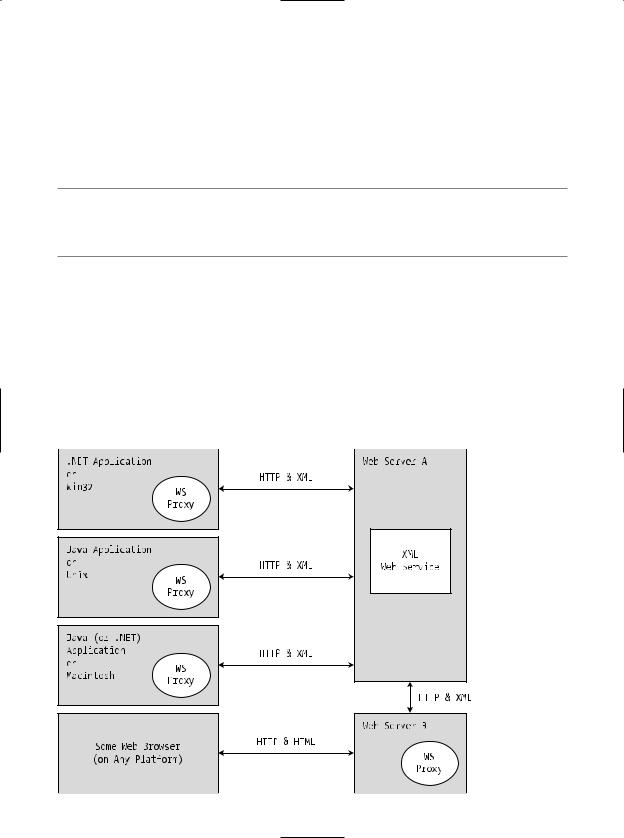

The Building Blocks of an XML Web Service

In addition to the managed code library that constitutes the exposed functionality, an XML web service requires some supporting infrastructure. Specifically, an XML web service involves the following core technologies:

•A discovery service (so clients can resolve the location of the XML web service)

•A description service (so clients know what the XML web service can do)

•A transport protocol (to pass the information between the client and the XML web service)

We’ll examine details behind each piece of infrastructure throughout this chapter. However, to get into the proper frame of mind, here is a brief overview of each supporting technology.

Previewing XML Web Service Discovery

Before a client can invoke the functionality of a web service, it must first know of its existence and location. Now, if you are the individual (or company) who is building the client and XML web service, the discovery phase is quite simple given that you already know the location of the web service in question. However, what if you wish to share the functionality of your web service with the world at large?

To do this, you have the option of registering your XML web service with a Universal Description, Discovery, and Integration (UDDI) server. Clients may submit request to a UDDI catalog to find a list of all web services that match some search criteria (e.g., “Find me all web services having to do real time weather updates”). Once you have identified a specific web server from the list returned via the UDDI query, you are then able to investigate its overall functionality. If you like, consider UDDI to be the white pages for XML web services.

In addition to UDDI discovery, an XML web service built using .NET can be located using DISCO, which is a somewhat forced acronym standing for Discovery of Web Services. Using static discovery (via a *.disco file) or dynamic discovery (via a *.vsdisco file), you are able to advertise the set of XML web services that are located at a specific URL. Potential web service clients can navigate to a web server’s *.disco file to see links to all the published XML web services.

Understand, however, that dynamic discovery is disabled by default, given the potential security risk of allowing IIS to expose the set of all XML web services to any interested individual. Given this, I will not comment on DISCO services for the remainder of this text.

■Note If you wish to activate dynamic discovery support for a given web server, look up the Microsoft Knowledge Base article Q307303 on http://support.microsoft.com.

Previewing XML Web Service Description

Once a client knows the location of a given XML web service, the client in question must fully understand the exposed functionality. For example, the client must know that there is a method named GetWeatherReport() that takes some set of parameters and sends back a given return value before the client can invoke the method. As you may be thinking, this is a job for a platform-, language-, and operating system–neutral metalanguage. Specifically speaking, the XML-based metadata used to describe a XML web service is termed the Web Service Description Language (WSDL).

In a good number of cases, the WSDL description of an XML web service will be automatically generated by Microsoft IIS when the incoming request has a ?wsdl suffix. As you will see, the primary consumers of WSDL contracts are proxy generation tools. For example, the wsdl.exe command-line utility (explained in detail later in this chapter) will generate a client-side C# proxy class from a WSDL document.

CHAPTER 25 ■ UNDERSTANDING XML WEB SERVICES |

923 |

Table 25-2. Members of the System.Web.Services Namespace

Type |

Meaning in Life |

WebMethodAttribute |

Adding the [WebMethod] attribute to a method or property in |

|

a web service class type marks the member as invokable via |

|

HTTP and serializable as XML. |

WebService |

This is an optional base class for XML web services built using |

|

.NET. If you choose to derive from this base type, your XML web |

|

service will have the ability to retain stateful information (e.g., |

|

session and application variables). |

WebServiceAttribute |

The [WebService] attribute may be used to add information to |

|

a web service, such as a string describing its functionality and |

|

underlying XML namespace. |

WebServiceBindingAttribute |

This attribute (new .NET 2.0) declares the binding protocol |

|

a given web service method is implementing (HTTP GET, HTTP |

|

POST, or SOAP) and advertises the level of web services |

|

interoperability (WSI) conformity. |

WsiProfiles |

This enumeration (new to .NET 2.0) is used to describe the web |

|

services interoperability (WSI) specification to which a web |

|

service claims to conform. |

|

|

The remaining namespaces shown in Table 25-1 are typically only of direct interest to you if you are interested in manually interacting with a WSDL document, discovery services, or the underlying wire protocols. Consult the .NET Framework 2.0 SDK documentation for further details.

Building an XML Web Service by Hand

Like any .NET application, XML web services can be developed manually, without the use of an IDE such as Visual Studio 2005. In an effort to demystify XML web services, let’s build

a simple XML web service by hand. Using your text editor of choice, create a new file named HelloWorldWebService.asmx (by convention, *.asmx is the extension used to mark .NET web service files). Save it to a convenient location on your hard drive (e.g., C:\HelloWebService) and enter the following type definition:

<%@ WebService Language="C#" Class="HelloWebService.HelloService" %> using System;

using System.Web.Services;

namespace HelloWebService

{

public class HelloService

{

[WebMethod]

public string HelloWorld()

{

return "Hello!";

}

}

}

For the most part, this *.asmx file looks like any other C# namespace definition. The first noticeable difference is the use of the <%@WebService%> directive, which at minimum must specify the name of the managed language used to build the contained class definition and the fully qualified