Pro ASP.NET 2.0 In CSharp 2005 (2005) [eng]

.pdf

988 C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T

The basic technique for a script injection attack is for the client to submit content with embedded scripting tags. These scripting tags can include <script>, <object>, <applet>, and <embed>. Although the application can specifically check for these tags and use HTML encoding to replace the tags with harmless HTML entities, that basic validation often isn’t performed.

Request Validation

Script injection attacks are a concern of all web developers, whether they are using ASP.NET, ASP, or other web development technologies. ASP.NET includes a feature designed to automatically combat script injection attacks, called request validation. Request validation checks the posted form input and raises an error if any potentially malicious tags (such as <script>) are found. In fact, request validation disallows any nonnumeric tags, including HTML tags (such as <b> and <img>), and tags that don’t correspond to anything (such as <abcd>).

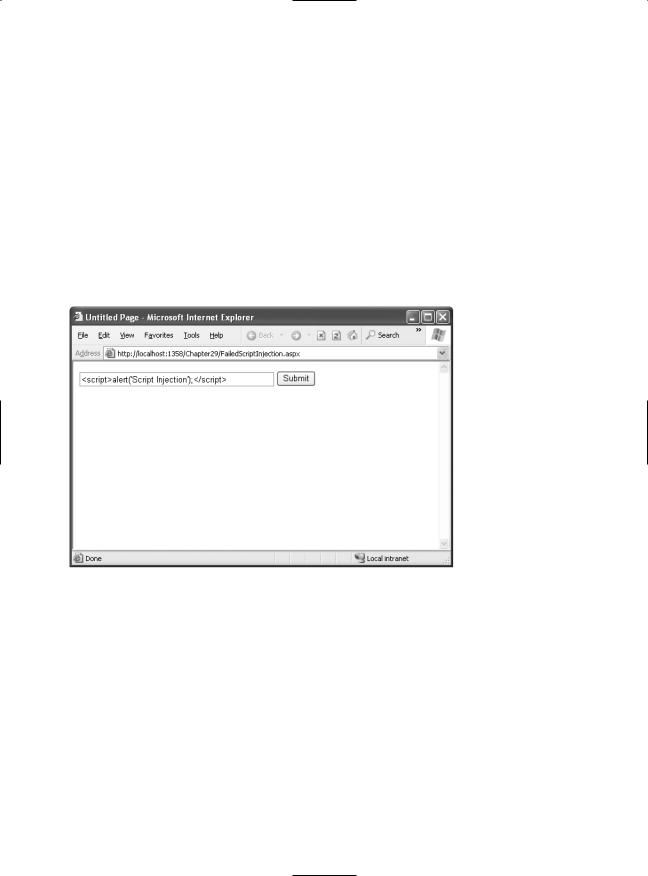

To test the script validation features, you can create a simple web page like the one shown in Figure 29-6. This simple example contains a text box and a button.

Figure 29-6. Testing a script injection attack

Now, try to enter a block of content with a script tag and then click the button. ASP.NET will detect the potentially dangerous value and generate an error. If you’re running the code locally, you’ll see the rich error page with detailed information, as shown in Figure 29-7. (If you’re requesting the page remotely, you’ll see only a generic error page.)

Disabling Request Validation

Of course, in some situations, the request validation rules are just too restrictive. For example, you might have an application where users have a genuine need to specify HTML tags (for example, when they enter an auction listing or a for-sale advertisement) or a block of XML data. In these situations, you need to specifically disable script validation using the ValidateRequest Page directive, as shown here:

<%@ Page ValidateRequest="false" ... %>

C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T |

989 |

Figure 29-7. A failed script injection attack

You can also disable request validation for an entire web application by modifying the web.config file. Add or set the validateRequest attribute of the <pages> element, as shown here:

<configuration>

<system.web>

<!-- Other settings omitted. -->

<pages validateRequest="false" />

</system.web>

</configuration>

Now, consider what happens if you attempt to display the user-supplied value in a label with this code:

protected void cmdSubmit_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

lblInfo.Text = "You entered: " + txtInput.Text;

}

If a malicious user enters the text <script>alert('Script Injection');</script>, the returned web page will execute the script, as shown in Figure 29-8.

Keep in mind that the script in a script injection attack is always executed on the client end. However, this doesn’t mean it’s limited to a single user. In many situations, user-supplied data is stored in a location such as a database and can be viewed by other users. For example, if a user supplies a script block for a business name when adding a business to a registry, another user who requests a full list of all businesses in the registry will be affected.

To prevent a script injection attack from happening when request validation is turned off, you need to explicitly encode the content before you display it using the Server object, as described earlier in this chapter.

C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T |

991 |

Client Callbacks

One of the main reasons that developers use JavaScript code is to avoid a postback. For example, consider the TreeView control, which lets users expand and collapse nodes at will. When you expand a node, the TreeView uses JavaScript to fetch the child node information from the server, and then it quietly inserts the new nodes. Without JavaScript, the page would need to be posted back so the TreeView could be rebuilt. The user would notice a sluggish delay, and the page would flicker and possibly scroll back to the beginning. On the server side, a considerable amount of effort would be wasted serializing and deserializing the view state information in each pass.

You’ve already seen how you can avoid this overhead and create smoother, more streamlined pages with a little JavaScript. However, most of the JavaScript examples you’ve seen so far have been self-contained—in other words, they’ve implemented a distinct task that doesn’t require interaction with the rest of the page model. This approach is great when it suits your need. For example, if all you need to do is show a pop-up message or a scrolling status display, you don’t need to interact with the server-side code. However, what happens if you want to make a truly dynamic page like in the TreeView example, one that can call a server-side method, wait for a response, and insert the new information dynamically, without triggering a postback? To design this solution, you need to think of a way for your client-side script to communicate with your server-side code. Although several options are available (such as web service calls), they are difficult to implement, require browser-specific or platform-specific functionality, and impose impractical limitations. ASP.NET 2.0 includes client callbacks, which are a built-in ASP.NET solution for this problem.

A client callback is a way for your client-side script to call a server-side method asynchronously to fetch some new information. Conceptually, it’s similar to the asynchronous image downloading example in the previous section. However, the image grid worked because images are really separate resources, not part of the page. You can’t use the same technique to insert dynamic text or arbitrary HTML. That’s where client callbacks come into the picture.

Creating a Client Callback

To create a client callback in ASP.NET, you first need to plan how the communication will work. Here’s the basic model:

1.At some point, a JavaScript event will fire, triggering the callback.

2.At this point, a single method on the server will execute. This method must have a fixed signature—it accepts a single string argument and returns a single string argument.

3.Once the page receives the response from the server-side method, it can use JavaScript code to modify the user interface accordingly.

The tricky part is the communication (which you’ll examine more closely in the next section). However, the ASP.NET architecture is designed to abstract away the communication process, so you can build a page that uses callbacks without worrying about this lower level, in much the same way you can take advantage of view state and the page life cycle.

In the next example, you’ll see a page with two drop-down lists boxes. The first list is populated with a list of regions from the Northwind database. This happens when the page first loads. The second list is left empty until the user makes a selection from the first list. At this point, the content for the second list is retrieved by a callback and inserted into the list (see Figure 29-10).

992 C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T

Figure 29-10. Filling in a list with a callback

Figure 29-11 diagrams how this process unfolds.

Figure 29-11. The stages of a callback

Building the Basic Page

The first step is to create the basic page, with two lists. It’s easy enough to fill the first list—you can tackle this task by binding the list declaratively to a data source control. In this example, the following SqlDataSource is used:

<asp:SqlDataSource ID="sourceRegions" runat="server" ProviderName="System.Data.SqlClient" ConnectionString="<%$ ConnectionStrings:Northwind %>" SelectCommand="SELECT * FROM Region" />

And here’s the list that binds to the data source:

<asp:DropDownList ID="lstRegions" Runat="server" DataSourceID="sourceRegions" DataTextField="RegionDescription" DataValueField="RegionID"/>

C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T |

993 |

Implementing the Callback

To receive a callback, your page must implement the ICallbackEventHandler interface, as shown here:

public partial class ClientCallback : ICallbackEventHandler { ... }

TThe ICallbackEventHandler interface defines two methods. RaiseCallbackEvent() receives event data from the browser as a string string parameter. It's triggered first. GetCallbackResult() is triggered next, and it returns the result back to the page.

■Note The key limitation of ASP.NET client callbacks is that they force you to transmit data as single strings.

If you need to pass more complex information (such as the result set with territory information, as in this example), you need to design a way to serialize your information into a string and deserialize it on the other side.

In this example, the string argument passed to RaiseCallbackEvent() contains the RegionID for the selected region. Using this information, theGetCallbackResult() method connects to the database and retrieves a list of all the territory records in that region. These results are joined into a single long string separated by the | character.

Here’s the complete code:

private string eventArgument;

public void RaiseCallbackEvent(string eventArgument)

{

this.eventArgument = eventArgument;

}

public string GetCallbackResult()

{

//Create the ADO.NET objects. SqlConnection con = new SqlConnection(

WebConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings["Northwind"].ConnectionString); SqlCommand cmd = new SqlCommand(

"SELECT * FROM Territories WHERE RegionID=@RegionID", con); cmd.Parameters.Add(new SqlParameter("@RegionID", SqlDbType.Int, 4)); cmd.Parameters["@RegionID"].Value = Int32.Parse(eventArgument);

//Create a StringBuilder that contains the response string.

StringBuilder results = new StringBuilder(); try

{

con.Open();

SqlDataReader reader = cmd.ExecuteReader(); // Build the response string.

while (reader.Read())

{

results.Append(reader["TerritoryDescription"]);

results.Append("|");

results.Append(reader["TerritoryID"]);

results.Append("||");

}

reader.Close();

994 C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T

}

finally

{

con.Close();

}

return results.ToString();

}

You can’t use declarative data binding in this example, because the callback method can’t directly access the controls on the page. Unlike in a postback scenario, when RaiseCallbackEvent() is called, the page isn’t in the process of being rebuilt. Instead, the RaiseCallbackEvent() method is called out-of-band to request some additional information. It’s up to your callback method to perform all the heavy lifting on its own.

Because the results need to be returned as a single string (and seeing as this string has to be reverse-engineered in JavaScript code), the code is a little awkward. A single pipe (|) separates the TerritoryDescription field from the TerritoryID field. Two pipes in a row (||) denote the start of a new row. For example, if you request RegionID 1, you might get a response like this:

Westboro|01581||Bedford|01730||Georgetow|01833|| ...

Clearly, this approach is somewhat fragile—if any of the territory records contain the pipe character, this will cause significant problems.

Writing the Client-Side Script

Client-side scripts involve an exchange between the server and the client. Just as the server needs a method to prepare the results, the client needs a method to process them. The method that handles the server response can take any name, but it need to accept two parameters, as shown here:

function ClientCallback(result, context) { ... }

The result parameter has the serialized string. In this example, it’s up to the client-side script to parse this string and fill the appropriate list box.

Here’s the complete client script code that you need for this task:

<script language="javascript">

function ClientCallback(result, context)

{

// Find the list box control.

var lstTerritories = document.forms[0].elements['lstTerritories'];

//Clear out any content in the list. lstTerritories.innerHTML= "";

//Get an array with a list of territory records. var rows = result.split('||');

for (var i = 0; i < rows.length - 1; ++i)

{

//Split each record into two fields. var fields = rows[i].split('|');

var territoryDesc = fields[0]; var territoryID = fields[1];

//Create the list item.

var option = document.createElement("option");

C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T |

995 |

//Store the ID in the value attribute. option.value = territoryID;

//Show the description in the text of the list item. option.innerHTML = territoryDesc; lstTerritories.appendChild(option);

}

}

</script>

One detail is missing. Although you’ve defined both sides of the message exchange, you haven’t actually hooked it up yet. What you need is a client-side trigger that calls the callback. In this case, you want to react to the onChange event of the region list:

lstRegions.Attributes["onClick"] = callbackRef;

The callbackRef is the JavaScript code that calls the callback. But how exactly do you need to write this line of code? Fortunately, ASP.NET gives you a handy GetCallbackEventReference() method that can construct the callback reference you need. Here’s how you use it in this example:

string callbackRef = Page.ClientScript.GetCallbackEventReference( this, "document.all['lstRegions'].value", "ClientCallback", "null");

The first argument is a reference to the ICallbackEventHandler object that will handle the call- back—in this case, the containing page. The second parameter is the information that the client will pass to the server (namely, the selected item in the lstRegions list box). The third parameter is the name of the client-side JavaScript function that will receive the results from the server callback. Finally, the last parameter is the context information that you want to pass to the client callback.

In this example, no extra information is needed.

Here’s the complete code for registering the callback when the page loads:

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

string callbackRef = Page.ClientScript.GetCallbackEventReference( this, "document.all['lstRegions'].value", "ClientCallback", "null");

lstRegions.Attributes["onClick"] = callbackRef;

}

This completes the solution.

Client Callbacks “Under the Hood”

Clearly, client callbacks represent a powerful feature that lets you build more seamless, dynamic pages. But client callbacks rely on some specific functionality that limits them to modern browsers. Many browsers may support JavaScript but not client callbacks. To properly assess whether you can use callbacks, you need to know a little bit more about how they work.

Client callbacks are based on the web-page DOM, which includes an XmlHttpRequest object. Although the DOM model and the XmlHttpRequest object are part of a cross-platform standard, they aren’t supported in all browser versions.

Internet browsers known to work with this feature include Internet Explorer 5, Netscape 6, Safari 1.2, and FireFox. You can check if a browser appears to support callbacks by interrogating the Request.Browser.SupportsCallback property.

Internet Explorer implements the XmlHttpRequest functionality using the ActiveX control Microsoft.XmlHttp. The only drawback is that this control won’t work if users have enabled tight security settings that prevent ActiveX controls from running. Other browsers don’t necessarily

C H A P T E R 2 9 ■ J AVA S C R I P T |

997 |

object-oriented controls, which render the JavaScript they need to optimize their appearance and their performance. This gives you the best of both worlds—object-oriented programming on the server and the client-side capabilities of JavaScript.

You can create any number of controls with JavaScript and the HTML document model. Common examples include rich menus, trees, and lists, many of which are available (some for free) at Microsoft’s http://www.asp.net community site. In the following sections, you’ll consider two custom controls that use JavaScript—a pop-up window generator and a rollover button.

Pop-Up Windows

For most people, pop-up windows are one of the Web’s most annoying characteristics. Usually, they deliver advertisements, but sometimes they serve the more valid purpose of providing helpful information or inviting the user to participate in a survey or promotional offer. A related variant is the pop-under window, which displays the new window underneath the current window. This way, the advertisement doesn’t distract the user until the original browser window is closed.

It’s fairly easy to show a pop-up window by using the window.open() function in a JavaScript block. Here’s an example:

<script language="javascript">

window.open('http://www.apress.com', 'myWindow', 'toolbar=0, height=500, width=800, resizable=1, scrollbars=1')

window.focus();

</script>

The window.open() function accepts several parameters. They include the link for the new page and the frame name of the window (which is important if you want to load a new document into that frame later, through another link). The third parameter is a comma-separated string of attributes that configure the style and size of the pop-up window. These attributes can include any of the following:

•height and width, which are set to pixel values

•toolbar, menuBar, and scrollbars, which can be set to 1 or 0 (or yes or no) depending on whether you want to display these elements

•resizable, which can be set to 1 or 0 depending on whether you want a fixed or resizable window border

•scrollbars, which can be set to 1 or 0 depending on whether you want to show scrollbars in the pop-up window

You can add a <script> block to your code to use the window.open() function, or you can use the window.open() function directly with a JavaScript event attribute. However, you may want to use the same functionality for several pages and possibly tailor the pop-up URL based on userspecific information. For example, you might want to check whether the user has already seen this advertisement, or you might want to pass the user name in the query string to the new window so that it can be incorporated in a message. In these scenarios, you need some level of programmatic control, and it makes sense to create a component that wraps these details. The next example develops a PopUp control to fill this role.

By deriving this component from Control, you gain the ability to add it to the Toolbox and drop it on a web form at design time. Here’s the definition for the PopUp control:

public class PopUp : Control { ... }