Olah G.A. - A Life of Magic Chemistry (2001)(en)

.pdf

40 A L I F E O F M A G I C C H E M I S T R Y

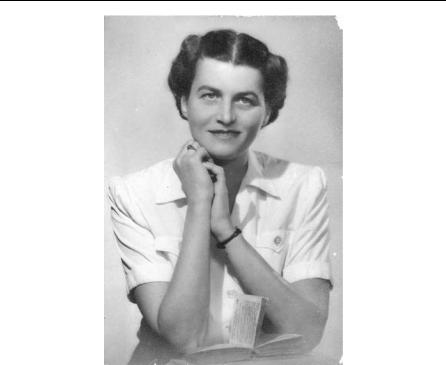

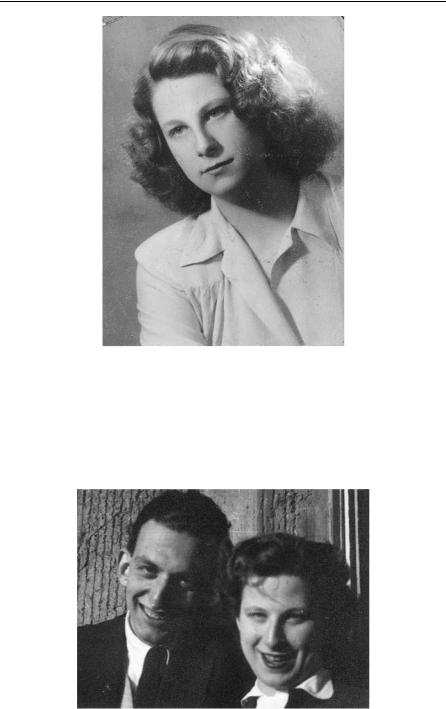

My mother around 1943

same time, it became a much more homogenous small country of some 10 million people. The capital city Budapest retained its million inhabitants, acting not unlike Vienna as an oversized head for a much smaller body. Budapest also maintained an unusual concentration of industry and centralized bureaucracy and remained the cultural and educational center of the country.

Budapest between the two World Wars was a vibrant, cultured city with excellent theaters, concert halls, opera house, and museums. The city consisted of ten districts. The working-class industrial outskirts of Pest had their row-houses, whereas the middle-class inner city had quite imposing apartment buildings. The upper classes and aristocracy lived in their villas in the hills of Buda.

Some of the social separation, however, was mitigated in the schools. There were remarkably good schools in Budapest, although as with much else it cannot be said that there was a uniformly high level of

G R O W I N G U P I N H U N G A R Y 41

education across the country. Much was written about the excellence of the gymnasia of Budapest (German-type composites of middle and high schools), particularly those that were frequented by some later successful scientists, artists, and musicians. For example, many Hungarianborn mathematicians, physicists, and engineers who later attained recognition (Neuman, Karman, Wigner, Szilard, Teller, among others) attended the same schools, where much emphasis was put on mathematics and physics. Winning the national competition in these topics for high school boys (the schools were still gender segregated and not much was ever said about the intellectual achievement of Hungarian girls, who clearly were at least as talented) was considered a predictor of outstanding future careers (Neuman, Teller).

I did not attend any of these schools, and there was, furthermore, no national competition in chemistry. After going to a public elementary school I attended the Gymnasium of the Piarist Fathers, a Roman Catholic religious teaching order, for eight years. Emphasis was on broad-based education, heavily emphasizing classics, history, languages, liberal arts, and even philosophy. The standards were generally high. Latin and German was compulsory for eight years and French (as a selective for Greek) for four years. During my high school years, at the recommendation of one of my teachers, I got my first teaching experience tutoring a middle school boy who had some difficulties with his grades. I enjoyed it and bought with my first earnings an Omega wristwatch, which I had for a quarter of century (I guess it was a good luck charm through some difficult times). I also took private lessons in French and English. In a small country such as Hungary, much emphasis was put on foreign languages. German was still very much a second language as a remnant of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, and I was fluent in it from early childhood.

We also received a solid education in mathematics, as well as some physics and chemistry. Although, among others, the physicist Lorand Eotvos and the chemist George Hevesy (Nobel Prize in 1943) attended the same Piarist school in earlier years, I learned about this only years later and cannot remember that anybody mentioned them as rolemodels during my school years. Classes were from 8 AM to 1 PM six days a week, with extensive homework for the rest of the day. I did

42 A L I F E O F M A G I C C H E M I S T R Y

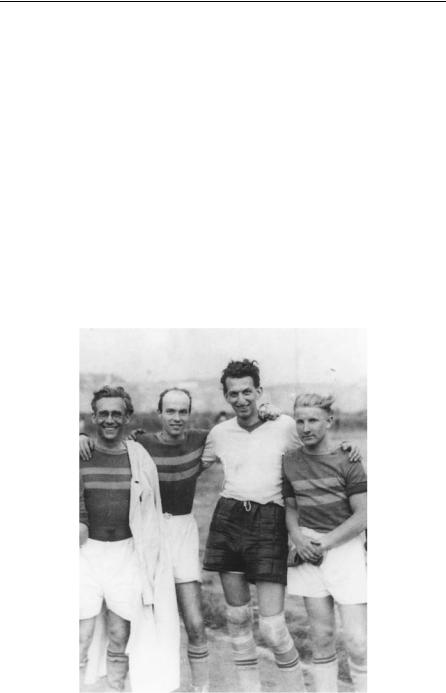

well throughout my school years in all subjects, except in physical education, where I remember I could never properly manage rope climbing and some exercises on gymnastic instruments. At the same time I was active and became reasonably good in different sports, including tennis, swimming, rowing, and soccer. In my time as a young faculty member at the Technical University I was the goalkeeper of the chemistry faculty team (a picture of which found its way onto the Swedish Academy Nobel poster published after my Prize).

My wife still teases me on occasion that I was always a stellar student (she uses the more contemporary expression ‘‘nerd’’) and school valedictorian. Studying, however, always came easy for me, and I enjoyed it. I was (and still am) an avid reader. In my formative school years I particularly enjoyed the classics, literature, and history, as well as, later on, philosophy. I believe obtaining a good general liberal

Goalie of the soccer team of the Chemistry faculty at the Technical University of

Budapest (1952)

G R O W I N G U P I N H U N G A R Y 43

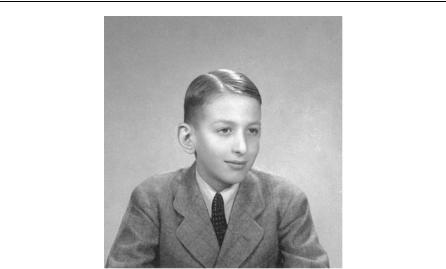

Not yet thinking about chemistry

education was a great advantage, because getting attached too early to a specific field or science frequently short-changes a balanced broad education. Although reading the classics in Latin at school age may not have been as fulfilling as it would have been at a more mature age, once I got interested in science I could hardly afford the time for such pleasurable diversions.

Besides the classics, Hungarian literature itself offered a wonderful treasure trove. It is regrettable that the works of many highly talented Hungarian poets and writers remained mostly inaccessible to the rest of the world because of the rather strange language in which they were written (Hungarian belongs to the so-called Finn-Ugoric family of languages, not related to any of the major languages). On the other hand, Western authors and poets were regularly translated into Hungarian, some of these translations being of extremely high quality. The Hungarian poet Janos Arany, for example, translated Shakespeare in a masterly way, although he taught himself English phonetically and could never speak it. I believe that many translations, such as ballads of Villon (one of my favorites), translated by the highly talented poet George Faludy, made them at least as enjoyable as the originals. Operas were sung only in Hungarian, which limited the chances for some tal-

44 A L I F E O F M A G I C C H E M I S T R Y

ented Hungarian singers to perform in the West (which has changed since).

Western movies were subtitled, but an active domestic movie industry also existed. An indication of the talented people in this industry is reflected in the subsequent role Hungarian e´migre´s played in the movie industries of the United States and England. These were not limited to movie producers and executives (Adolf Zukor, Paramount Pictures; William Fox, 20th Century Fox; Sir Alexander Korda). Who would guess, considering the thickly accented English most Hungarians used to speak, that Leslie Howard’s (Professor Higgins in Pygmalion) mother tongue was this rather obscure and difficult language? What a difference indeed from the charming accent of Zsa Zsa Gabor. On the wall of Zukor’s office there was an inscription: ‘‘It is not enough to be Hungarian, you must be talented, too.’’ Zukor was quoted to add in a low voice, ‘‘But it may help.’’

The standards of theatrical and musical life were also extremely high. Franz Liszt (a native Hungarian who achieved his fame as a virtuoso pianist and composer) established a Music Conservatory in Budapest around 1870, which turned out scores of highly talented graduates, including such composers as Kodaly and Bartok and conductors such as Doraty, Ormandy, Solti, and Szell.

Good teachers can have a great influence on their students. As I mentioned, besides the classics, humanities, history, and languages I also received a good education in mathematics and had some inspiring science teachers. I particularly remember my physics teacher, Jozsef

¨

Oveges, who I understand later introduced the first television science programs in Hungary, which made him well known and extremely popular. He was a very inspiring teacher who used simple but ingenious experiments to liven up his lectures. I must confess that I do not remember my chemistry teacher, who must have made less of an impression on me. When a friend received a chemistry set for Christmas one year, we started some experiments in the basement of his home. This was probably when I first experienced the excitement of some of the magic of chemistry. For example, we observed with fascination bubbles of carbon dioxide evolving when we dropped some sodium bicarbonate into vinegar or muriatic acid. Little did I expect to repeat

G R O W I N G U P I N H U N G A R Y 45

this experiment with superacidic ‘‘magic acid’’ years later, when, unexpectedly, no bubbles were formed (see Chapter 8). After going through some of the routine experiments described in the manual that came with the chemistry set, we boldly advanced to more interesting ‘‘individual’’ experiments. The result was an explosion followed by a minor fire and much smoke, which destroyed the chemistry set and ended the welcome for our experimentation. I cannot remember thinking much about chemistry thereafter, until I entered university.

The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 initially affected our lives little. Hungary stayed out of the war until Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, when it was pressured to join Germany, with disastrous consequences. In 1943, a whole Hungarian army corps was destroyed in Russia, and Hungary, not unlike Romania, subsequently tried to quit the war. In the spring of 1944, Hungary attempted the break with Germany but was unsuccessful, and the Gestapo with their Hungarian allies, the Arrow Crosses, took over and instituted a regime of terror. Much has been written about this horrible period, when hundreds of thousands perished, until World War II fi- nally ended. The human mind mercifully is selective, and eventually we tend to remember only the more pleasant memories. I do not want to relive here in any detail some of my very difficult, even horrifying, experiences of this period, hiding out the last months of the war in Budapest. Suffice it to say that my parents and I survived. My only brother Peter (three years my senior), however, perished at the end of World War II in a Russian prisoner of war camp, where he was taken together with tens of thousands of civilians only to satisfy claimed numbers of prisoners of war. My home town, beautiful but badly ravaged Budapest, also survived and started recovering. However, soon again difficult times followed when a brief period of emerging democracy ended with the Communist takeover.

I graduated high school (gymnasium) right at the end of the war in the spring of 1945. We needed to pass a very tough two-day examination (matriculation or baccalaureate). This included, for example, translation of selected literature passages—without the help of a dictionary—not only from foreign languages (including Latin) into Hungarian, but also vice versa, not a minor effort. Having passed this

46 A L I F E O F M A G I C C H E M I S T R Y

My brother Peter in 1943

barrier, it was time to think seriously about my future. It was clear that my interests in the humanities, particularly literature and history, did not offer much future in postwar Hungary. One inevitably was forced to think about more ‘‘practical’’ occupations. I had no interest in business, law, or medicine but was increasingly attracted to the sciences, which I always felt in a way to be closely related to the arts and humanities. My eventual choice of chemistry was thus not really out of character. I was attracted to chemistry probably more than anything else by its broad scope and the opportunities it seemed to offer. On one hand, chemistry is the key to understanding the fundamentals of biological processes and maybe life itself. It is also an important basis of the life and health sciences. On the other hand, chemists make compounds, including the man-made materials, pharmaceuticals, dyes, and fuels essential to everyday life. It also seemed to be a field in which, even in a poor, small country, one could find opportunities for the future.

My choice of chemistry as a career was from a practical point of view also not unusual. I read years later that Eugene Wigner, the

G R O W I N G U P I N H U N G A R Y 47

Hungarian-born physicist, when he was seventeen, was asked by his father (a businessman) what he wanted to do. The young Wigner replied that he had in mind to become a theoretical physicist. ‘‘And exactly how many jobs are there in Hungary for theoretical physicists?’’ his father inquired. ‘‘Perhaps three,’’ replied young Wigner. The discussion ended there and Wigner was persuaded to study chemical engineering. Similarly, the mathematician John von Neuman initially also studied chemistry, although they both soon changed to their field of real interest.

I entered the Technical University of Budapest immediately after the end of World War II. It had been established some 150 years earlier as the Budapest Institute of Technology. Because the Austro-Hungarian education system closely followed the German example, the Technical University of Budapest developed along the lines of German technical universities. Many noted scientists of Hungarian origin such as Michael Polanyi, Denis Gabor (Nobel Prize in Physics 1971), George Hevesy (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1943), Leo Szilard, Theodor von Karman, Eugene Wigner (Nobel Prize in Physics 1963), John von Neuman, Edward Teller, and others have studied there at one time or other, generally, however, only for short periods of time. Most completed their studies in Germany or Switzerland usually in physics or mathematics, and their career carried them subsequently to England or the United States. To my knowledge, I am the only one who got my entire university education at that institution and who subsequently was also on its faculty. I was proud to be recognized as such when my alma mater welcomed me back after many years in 1988 and gave me an honorary Doctor of Science degree.

Formally, chemistry was taught at the Technical University under the Faculty of Chemical Engineering, but it was really a solid chemical education (along the lines of related German technical universities), with a minimum of engineering courses, in sharp contrast to what American universities teach as chemical engineering. Classes were relatively small. We started with a class of about 80, but the number was rapidly pared down during the first year to half by rather demanding ‘‘do or die’’ examinations (including comprehensive oral examinations). Those who failed could not continue. This was a rather harsh

48 A L I F E O F M A G I C C H E M I S T R Y

process, but laboratory facilities were so limited that only a few could be accommodated. The laboratory training was thorough. For example, in the organic laboratory we did some 40 synthetic preparations (based on Gatterman’s book). It certainly gave a solid foundation.

In contrast to the excellent general education some of the gymnasia of Budapest provided their students, the chemical education at the Technical University in retrospect was very one-sided. The emphasis was on memorizing a large amount of data and not so much on fostering understanding and critical probing. Empirical chemistry, including such fields as gravimetric analysis, the recounting of endless compounds and their reactions, was emphasized, with little attention given to the newer trends of chemistry developing in the Western countries. However, I was well prepared for self-study and gained much through long hours in the library, which opened up many new vistas. There were also other very positive aspects of my university education. Many of our professors through their lectures were able to induce in us a real fascination and love for chemistry, which I consider the most important heritage of my university days.

After completing my studies and thesis, in June 1949 I was named to a faculty position as an assistant professor in Zemplen’s organic chemical institute. The following month I married my boyhood love.

I met Judy Lengyel, a shy girl not much interested in boys, in 1943 during a vacation at a summer resort not far from Budapest. I was 16, and she was 14. Little did I realize at the time that this would become the most significant and happiest event of my life. Although fairytale things are not supposed to happen in real life, we were married six years later and celebrated our golden wedding anniversary in 1999. If anybody was blessed with a happy marriage and life partnership, I am, there are no words that can express it adequately.

At the time of our marriage, Judy worked as a secretary at the Technical University. She subsequently studied chemistry and, after completing her studies, joined our research. To this day, however, I am not sure that she has completely forgiven me for what she probably rightly recollects was my enrolling her to study chemistry (taking advantage of my faculty position) without really getting her prior full approval. Even if I were guilty in this regard, my intentions were good. The life

G R O W I N G U P I N H U N G A R Y 49

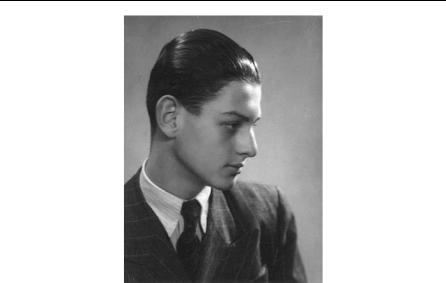

The shy girl Judy Lengyel

As newlyweds in 1950