Color Atlas of Neurology (Thieme 2004)

.pdf

Central Nervous System

252

CNS Infections

Transmissible Spongiform

Encephalopathies

The transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) are characterized by spongiform histological changes in the brain (vacuoles in neurons and neuropil), transmissibility to humans by way of infected tissue or contaminated surgical instruments, and, in some cases, a genetic determination. TSEs are transmitted by nucleic acidfree proteinaceous particles called prions and are associated with mutations in prion protein (PrP); they are therefore referred to as prion diseases.

Normal cellular prion protein (PrPc) is synthesized intracellularly, transported to the cell membrane, and returned to the cell interior by endocytosis. Part of the PrPc is then broken down by proteases, and another fraction is transported back to the cell surface. The physiological function of PrPc is still unknown. It is found in all mammalian species and is especially abundant in neurons. PRNP, the gene responsible for the expression of PrPc in man, is found on the short arm of chromosome 20. PRNP mutations yield the mutated form of PrP ( PrP) that causes the genetic spongiform encephalopathies. Another mutated form of PrP (PrPsc) causes the infectious spongiform encephalopathies. PrPsc induces the conversion of PrPc to PrPsc in the following manner: PrPsc enters the cell and binds with PrPc to yield a heterodimer. The resulting conformational change in the PrPc molecule (α-helical structure) and its interaction with a still unidentified cellular protein (protein X) transform it into PrPsc (#-sheet structure). Protein X is thought to supply the energy needed for protein folding, or at least to lower the activation energy for it. PrPsc cannot be formed in cells lacking PrPc. Mutated PrPsc presumably reaches the CNS by axonal transport or in lymphatic cells; these forms of transport have been demonstrated in forms of spongiform encephalopathies that affect domestic animals, e. g., scrapie (in sheep) and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). PrP and PrPsc cannot be broken down intracellularly and therefore accumulate within the cells. Partial proteolysis of these proteins yields a protease-resistant molecule (PrP 27–30) that polymerizes to form amyloid, which, in turn, induces further neu-

ropathological changes. PrP and amyloid have been found in certain myopathies (such as inclusion body myositis, p. 344); others involve an accumulation of PrP (PrP overexpression myopathy).

! Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD)

CJD is a very rare disease, arising in ca. 1 person per 106 per year. It usually affects older adults (peak incidence around age 60). 85–90% of cases are sporadic (due to a spontaneous gene mutation or conformational change of PrPc to PrPsc); 5–15% are familial (usually autosomal dominant); and very rare cases are iatrogenic (transmitted by contaminated neurosurgical instruments or implants, growth hormone, and dural and corneal grafts). It usually progresses rapidly to death within 4–12 months of onset, though the survival time in individual cases varies from a few weeks to several years. Early manifestations are not typically seen, but may include fatigability, vertigo, cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia, hallucinations, increasing apathy, and depression. The principal finding is a rapidly progressive dementia associated with myoclonus, increased startle response, motor disturbances (rigidity, muscle atrophy, fasciculations, cerebellar ataxia), and visual disturbances. Late manifestations include akinetic mutism, severe myoclonus, epileptic seizures, and autonomic dysfunction. A new variant of CJD has recently arisen in the United Kingdom; unlike the typical form, it tends to affect younger patients, produces mainly behavioral changes in its early stages, and is associated with longer survival (though it, too, is fatal). It is thought to be caused by the consumption of beef from cattle infected with BSE. Diagnosis: EEG (1 Hz periodic biphasic or triphasic sharp-wave complexes), CT (cortical atrophy), T2/proton-weighted MRI (bilateral hyperintensity in basal ganglia in ca. 80%), CSF examination (elevation of neuron-specific enolase, S100# or tau protein concentration; presence of protein 14–3-3).

!Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker Disease (GSS) and Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI)

See pp. 114 and 280.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Accumulation of PrP amyloid in neuron

Normal PrP conformation |

|

|

Spongiform dystrophy of gray |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

matter |

|

PRNP |

|

|

|

|

PrPc synthesis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

(nucleus) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PRNP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PrPc trans- |

|

|

mutation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ported to |

|

Infectious |

Mutated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

cell surface |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

prion |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PrPsc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

protein |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reab- |

Heterodimer |

(6PrP) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

sorbed, |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

formation |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

trans- |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Conversion of |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

ported |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

back to cell |

PrPc to PrPsc |

|

|

|

surface

Breakdown by cellular |

Protease resistance |

||

proteases (lysosomes) |

of PrPsc |

|

accumulation of PrPsc, |

|

|||

|

storage |

of |

amyloid |

Normal PrPc synthesis

Infectious prion disease

Continuous sharp wave complexes (CJD)

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)

Spontaneous conversion of 6PrP zu PrPsc

Hereditary prion disease

Dementia,

ataxia,

myoclonus, visual disturbances, behavioral changes

Central Nervous System

253

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Brain Tumors

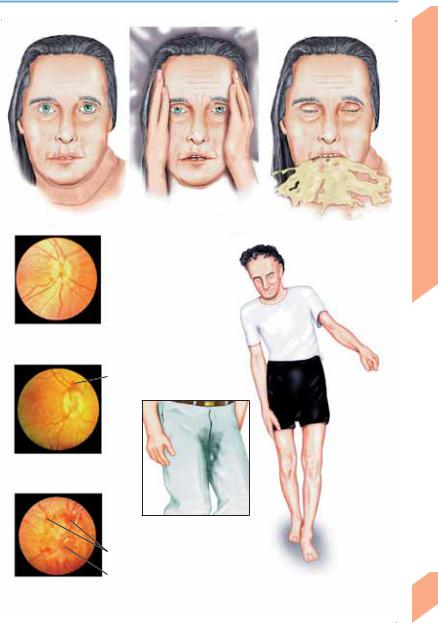

Symptoms and Signs

The clinical manifestations of a brain tumor may range from a virtually asymptomatic state to a constellation of symptoms and signs that is specific for a particular type and location of lesion. The only way to rule out a brain tumor for certain is by neuroimaging (CT or MRI).

! Nonspecific Manifestations

Tumors whose manifestations are mainly nonspecific include astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, cerebral metastasis, ependymoma, meningioma, neoplastic meningitis, and primary CNS lymphoma.

Behavioral changes. Patients may complain of easy fatigability or exhaustion, while their relatives or co-workers may notice lack of concentration, forgetfulness, loss of initiative, cognitive impairment, indifference, negligent task performance, indecisiveness, slovenliness, and general slowing of movement. Such manifestations are often mistaken for signs of depression or stress. Apathy, obtundation, and somnolence worsen as the disease progresses. There may also be increasing confusion, disorientation, and dementia.

Headache. More than half of patients with brain tumors suffer from headache, and many headache patients fear that they might have a brain tumor. If headache is the sole symptom, the neurological examination is normal, and the headache can be securely classified as belonging to one of the primary types (p. 182 ff), then a brain tumor is very unlikely. Neuroimaging is indicated in patients with longstanding headache who report a change in their symptoms. The clinical features of headache do not differentiate benign from malignant tumors.

Nausea, vertigo, and malaise are frequent, though often vague, complaints. The patient feels unsteady or simply “different.” Vomiting (sometimes on an empty stomach) is less common and not necessarily accompanied by nausea; there may be spontaneous, projectile vomiting.

may be present earlier in milder form. Hemiparesis, aphasia, apraxia, ataxia, cranial nerve palsies, or incontinence may occur depending on the type and location of the tumor.

Intracranial hypertension (elevated ICP) (p. 158) may arise without marked focal neurological dysfunction because of a medulloblastoma, ependymoma of the fourth ventricle, cerebellar hemangioblastoma, colloid cyst of the 3rd ventricle, craniopharyngioma, or glioblastoma (e. g. of the frontal lobe or corpus callosum). Cervical tumors very rarely cause intracranial hypertension. Papilledema, if present, is not necessarily due to a brain tumor, nor does its absence rule one out. Papilledema does not impair vision in its acute phase.

! Specific Manifestations

Some tumors produce symptoms and signs that are specific for their histological type, location, or both. These tumors include craniopharyngioma, olfactory groove meningioma, pituitary tumors, cerebellopontine angle tumors, pontine glioma, chondrosarcoma, chordoma, glomus tumors, skull base tumors, and tumors of the foramen magnum. In general, these specific manifestations are typically found when the tumor is relatively small and are gradually overshadowed by nonspecific manifestations (described above) as it grows.

Epileptic seizures. Focal or generalized seizures arising in adulthood should prompt evaluation

254for a possible brain tumor.

Focal neurological signs usually become prominent only in advanced stages of the disease but

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

Behavioral changes |

Headache |

Early papilledema

(irregular margins, disk elevation, reduced venous pulsation)

Peripapillary hemorrhage

Advanced papilledema

Incontinence, focal neurological signs

Hemorrhage

Blurring of disk

Fully developed margins papilledema

Nausea, vomiting

Vertigo, unsteady gait

Central Nervous System

255

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Brain Tumors

Benign Brain Tumors

! Astrocytoma (WHO grades I and II)

Astrocytomas arise from blastomatous astrocytes. They are classified as benign (WHO grade I) or semibenign (WHO grade II) according to their histological features (p. 377).

Pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade I) is a slowly growing tumor that mainly occurs in children and young adults and usually arises in the cerebellum, optic nerve, optic chiasm, hypothalamus, or pons. It is not uncommonly found in the setting of neurofibromatosis I. There may be a relatively long history of headache, abnormal gait, visual impairment, diabetes insipidus, precocious puberty, or cranial nerve palsies before the tumor is discovered.

Low-grade astrocytoma (WHO grade II). Fibrillary astrocytoma is more common than the gemistocytic and protoplasmic types. These tumors most commonly arise in the frontal and temporal lobes and often undergo malignant transformation to grades III and IV over the course of several years. They may be calcified. They may produce epileptic seizures and behavioral changes.

Oligodendroglioma (WHO grade II) usually appears in the 4th or 5th decade of life. It tends to arise at or near the cortical surface of the frontal and temporal lobes and may extend locally to involve the leptomeninges. Oligodendrogliomas are often partially calcified. Tumors of mixed histology (oligodendrocytoma plus astrocytoma) are called oligoastrocytomas.

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (WHO grade II) is a rare tumor that mainly arises in the temporal lobes of children and young adults and is associated with epileptic seizures in most cases. It can progress to a grade III tumor.

! Meningioma (WHO grade I)

CNS but are most often found in supratentorial (falx, parasagittal region, sphenoid wing, cerebral convexities), infratentorial (tentorium, cerebellopontine angle, craniocervical junction), and spinal locations. Multiple or intraventricular meningioma is less common. Extracranial meningiomas rarely arise in the orbit, skin, or nasal sinuses. Familial meningioma is seen in hereditary disorders such as type II neurofibromatosis.

! Choroid Plexus Papilloma (WHO grade I)

This rare tumor most commonly arises in the (left) lateral ventricle in children and in the 4th ventricle in adults. Signs of intracranial hypertension, due to obstruction of CSF flow, are the most common clinical presentation and may arise acutely.

! Hemangioblastoma (WHO grade I)

These solid or cystic tumors usually arise in the cerebellum (from the vermis more often than the hemispheres) and produce vertigo, headache, truncal ataxia, and gait ataxia. Obstructive hydrocephalus may occur as an early manifestation. 10% of cases are in patients with von Hip- pel–Lindau disease (p. 294).

! Ependymoma (WHO grades I–II)

Ependymomas most commonly arise in children, adolescents, and young adults. They may arise in the ventricular system (usually in the fourth ventricle) or outside it; they may be cystic or calcified. Subependymoma of the fourth ventricle (WHO grade I) may appear in middle age or later. Spinal ependymomas may arise in any portion of the spinal cord.

Meningiomas are slowly growing, usually benign, dural-based extraaxial tumors that are thought to arise from arachnoid cells. Twelve histological subtypes have been identified. Meningiomas tend to recur if they are not totally resected. They may involve not only the dura mater but also the adjacent bone (manifesting

256usually as hyperostosis, more rarely as thinning) and may infiltrate or occlude the cerebral venous sinuses. They can occur anywhere in the

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

|

Brain Tumors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Supratentorial |

Convexity meningioma causing |

|

sites |

bone destruction |

|

Supratentorial sites

Infratentorial site

Common sites of meningioma

Plexus papilloma (3rd ventricle)

Ependymoma (craniocervical junction, extraventricular site)

Cystic hemangioblastoma (cerebellum)

Hemangioblastoma

(von Hippel-Lindau

syndrome)

MRI (sagittal T1-weighted image)

Central Nervous System

257

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

Tumors in Specific Locations

|

! Supratentorial Region |

|

|

||

|

Colloid cyst of 3rd ventricle. These cysts filled |

||||

|

with gelatinous fluid are found in proximity to |

||||

|

the interventricular foramen (of Monro). Small |

||||

|

colloid cysts may remain asymptomatic, but |

||||

|

large ones cause acute or chronic obstructive hy- |

||||

|

drocephalus (p. 162). Sudden obstruction of the |

||||

|

foramen causes acute intracranial hypertension, |

||||

|

sometimes with loss of consciousness. Sympto- |

||||

System |

matic colloid cysts can be surgically removed |

||||

with stereotactic, neuroendoscopic, or open |

|||||

techniques. |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Craniopharyngioma (WHO grade I). Adamanti- |

||||

Nervous |

nomatous |

craniopharyngioma is suprasellar |

|||

visual field defects, hormonal deficits (growth |

|||||

|

tumor of children and adolescents that has both |

||||

|

cystic and calcified components. It produces |

||||

Central |

retardation, thyroid and adrenocortical insuffi- |

||||

ciency, diabetes insipidus), and hydrocephalus. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Large tumors can cause behavioral changes and |

||||

|

epileptic seizures. Papillary craniopharyngioma |

||||

|

is a tumor of adults that usually involves the 3rd |

||||

|

ventricle. |

|

|

|

|

|

Pituitary adenomas (WHO grade I). Adenomas |

||||

|

smaller than 10 mm, called microadenomas, are |

||||

|

usually hormone-secreting, while those larger |

||||

|

than 10 mm, called macroadenomas, are often |

||||

|

non–hormone-secreting. In addition to possible |

||||

|

hormone secretion, these tumors have intrasel- |

||||

|

lar (hypothyroidism, adrenocortical |

hormone |

|||

|

deficiency, |

amenorrhea reflecting |

anterior |

||

|

pituitary insufficiency, and, rarely, diabetes in- |

||||

|

sipidus), suprasellar (chiasmatic lesions, p. 82, |

||||

|

hypothalamic compression, |

hydrocephalus), |

|||

|

and parasellar manifestations (headache, defi- |

||||

|

cits of CN III–VI, encirclement of the ICA by |

||||

|

tumor, diabetes insipidus), which gradually pro- |

||||

|

gress as the tumor enlarges. Hemorrhage or in- |

||||

|

farction of a pituitary tumor can cause acute |

||||

|

pituitary failure (cf. Sheehan’s postpartum |

||||

|

necrosis of the pituitary gland). Prolactinomas |

||||

|

(prolactin-secreting tumors) elevate the serum |

||||

|

prolactin concentration above 200 µg/l, in dis- |

||||

|

tinction to the less pronounced secondary hy- |

||||

|

perprolactinemia (usually |

!200 µg/l) as- |

|||

sociated with as pregnancy, parasellar tumors,

258dopamine antagonists (neuroleptics, metoclopramide, reserpine), and epileptic seizures. Pro-

lactinomas can cause secondary amenorrhea,

galactorrhea, and hirsutism in women, and headache, impotence, and galactorrhea (rarely) in men. Growth hormone-secreting tumors cause gigantism in adolescents and acromegaly in adults. Headache, impotence, polyneuropathy, diabetes mellitus, organ changes (goiter), and hypertension are additional features. ACTHsecreting tumors cause Cushing disease.

Tumors of the pineal region. The most common tumor of the pineal region is germinoma (WHO grade III), followed by pineocytoma (WHO grade I) and pineoblastoma (WHO grade IV). The clinical manifestations include Parinaud syndrome (p. 358), hydrocephalus, and signs of metastatic dissemination in the subarachnoid space (p. 262).

! Infratentorial Region

Acoustic neuroma (WHO grade I) is commonly so called, though it is in fact a schwannoma of the vestibular portion of CN VIII. Early manifestations include hearing impairment (rarely sudden hearing loss), tinnitus, and vertigo. Larger tumors cause cranial nerve palsies (V, VII, IX, X), cerebellar ataxia, and sometimes hydrocephalus. Bilateral acoustic neuroma is seen in neurofibromatosis II.

Chordoma arises from the clivus and, as it grows, destroys the surrounding bone tissue and compresses the brain stem, causing cranial nerve palsies (III, V, VI, IX, X, XII), pituitary dysfunction, visual field defects, and headache.

Paragangliomas. This group of tumors includes pheochromocytoma (arising from the adrenal medulla), sympathetic paraganglioma (arising from neuroendocrine cells of the sympathetic system), and parasympathetic ganglioma or chemodetectoma (arising from parasympathetically innervated chemoreceptor cells). The lastnamed is a highly vascularized tumor that may grow invasively. It arises from the glomus body.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

Retrosellar

spread

|

|

|

|

|

III |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pons |

|

||

Colloid cyst |

|

|

|

Cystic |

|

|

Bone destruction |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

craniopharyngioma |

|

||

Optic chiasm |

|

Infundibulum |

|

||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Pituitary adenoma

Pineal tumor

Sphenoid sinus

Acoustic neuroma |

Dorsum sellae |

|

Clivus

Chordoma

Inferior petrosal sinus

MRI (axial T1-weighted image)

Central Nervous System

259

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

Malignant Tumors

! Anaplastic Astrocytoma (WHO grade III)

|

and Glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) |

|

|

These infiltrative, rapidly growing tumors usu- |

|

|

ally arise in adults between the ages of 40 and |

|

|

65. They usually involve the cerebral hemi- |

|

|

spheres, but are sometimes found in infraten- |

|

|

torial locations (brain stem, cerebellum, spinal |

|

|

cord). They are occasionally multicentric or dif- |

|

|

fuse (gliomatosis cerebri is extremely rare). Infil- |

|

System |

trative growth across the corpus callosum to the |

|

opposite side of the head is not uncommon |

||

(“butterfly glioma”). These tumors are often |

||

|

||

|

several centimeters in diameter by the time of |

|

Nervous |

diagnosis. Even relatively small tumors can pro- |

|

CT and MRI reveal ringlike or garlandlike con- |

||

|

duce considerable cerebral edema. Metastases |

|

|

outside the CNS (bone, lymph nodes) are rare. |

|

Central |

trast around a hypointense center. |

|

! Primary Cerebral Lymphoma |

||

|

||

|

(WHO grade IV) |

These tumors are usually non-Hodgkin lymphomas of the B-cell type and are only rarely of the T-cell type. They are commonly associated with congenital or acquired immune deficiency (Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome; immune suppression for organ transplantation, AIDS) and can arise in any part of the CNS (80% supratentorial, 20% infratentorial). Headache, cranial nerve palsies, polyradiculoneuropathy, meningismus, and ataxia suggest (primary) leptomeningeal involvement. Ocular manifestations: Infiltration of the uvea and vitreous body (visual disturbances; slit-lamp examination). Moreover, lymphomas may occur as solitary or multiple tumors or may spread diffusely through CNS tissue (periventricular zone, deep white matter). They produce local symptoms and also such general symptoms as psychosis, dementia, and anorexia. CT reveals them as hyperdense lesions surrounded by edema, usually with homogeneous contrast absorption and with little or no mass effect. MRI is more sensitive for lymphoma than CT; it reveals the extent of surrounding edema and is especially useful for the detection of spinal, leptomeningeal, and multilocular involve-

260ment. CSF examination reveals malignant cells in the early stages of the disease; the CSF protein

concentration is not necessarily elevated. Biop-

sies and/or CSF serology for diagnosis should be performed before treatment is initiated, because some of the drugs used, particularly corticosteroids, can make the disease more difficult to diagnose.

!Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma (WHO grade III)

This rare form of oligodendroglioma responds well to chemotherapy with procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine (PCV). As histological confirmation of cellular anaplasia (the defining criterion for grade III) can be difficult, the diagnosis must sometimes be based on the clinical and radiological findings. There may be leptomeningeal dissemination or meningeal gliomatosis.

! Anaplastic Ependymoma (WHO grade III)

These tumors may have subarachnoid and (rarely) extraneural metastases, e. g., to the liver, lungs and ovaries.

!Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET; WHO grade IV)

A PNET is a highly malignant embryonal tumor of the CNS that mainly arises in children. PNETs arising in the cerebellum, called medulloblastomas, are most commonly found in the vermis; they tend to metastasize to the leptomeninges and subarachnoid space (drop metastasis). The primary tumor and its metastases are best seen on MRI; they may appear in CT scans as areas of hyperdensity.

! Primary Cerebral Sarcoma (WHO grade IV)

The very rare tumors in this group, including meningeal sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma, all tend to recur locally and only rarely metastasize.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

10%

11%

7%

31% |

5% |

32%

Topographic distribution of anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma

|

|

|

Non-Hodgkin |

||

|

|

|

lymphoma (dorsal |

||

|

|

|

brain stem region) |

||

Multifocal primary |

|

|

MRI (contrast-enhanced, |

||

cerebral lymphoma |

|

sagittal T1-weighted image) |

|||

|

|

Focal calcification |

|||

|

|

|

Anaplastic |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

ependymoma |

||

|

|

|

4th ventricle |

||

|

|

|

|

|

3rd ventricle |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anaplastic oligodendroglioma

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (medulloblastoma)

Central Nervous System

261

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.