- •Contents

- •Contents at a Glance

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface

- •Is This Book for You?

- •How This Book Is Organized

- •How to Use This Book

- •Doing the Exercises

- •Conventions Used in This Book

- •What the Icons Mean

- •About the CD-ROM

- •Other Information

- •Contacting the Author

- •Foreword

- •Credits

- •About the Author

- •Summary

- •AutoCAD’s Advantages

- •Comparing AutoCAD and AutoCAD LT

- •Starting AutoCAD and AutoCAD LT

- •Creating a New Drawing

- •Using the AutoCAD and AutoCAD LT Interface

- •Creating a New Folder

- •Using the Interface

- •Saving a Drawing

- •Closing a Drawing and Exiting from AutoCAD and AutoCAD LT

- •Summary

- •Creating a New Drawing from a Template

- •Working with Templates

- •Opening a Drawing with Default Settings

- •Opening an Existing Drawing

- •Using an Existing Drawing as a Prototype

- •Saving a Drawing Under a New Name

- •Summary

- •The Command Line and Dynamic Input

- •Command Techniques

- •Of Mice and Pucks

- •Getting Help

- •Summary

- •Typing Coordinates

- •Displaying Coordinates

- •Picking Coordinates on the Screen

- •Overriding Coordinate Settings

- •Locating Points

- •Summary

- •Choosing Unit Types

- •Drawing Limits

- •Understanding Scales

- •Creating a Title Block

- •Specifying Common Setup Options

- •Customizing with the MVSETUP Command

- •Using the Setup Wizards

- •Summary

- •Using the LINE Command

- •Drawing Rectangles

- •Drawing Polygons

- •Creating Construction Lines

- •Creating Rays

- •Summary

- •Drawing Circles

- •Drawing Arcs

- •Creating Ellipses and Elliptical Arcs

- •Making Donuts

- •Placing Points

- •Summary

- •Panning

- •Using the ZOOM Command

- •Using Aerial View

- •Saving Named Views

- •Working with Tiled Viewports

- •Using Snap Rotation

- •Understanding User Coordinate Systems

- •Creating Isometric Drawings

- •Summary

- •Editing a Drawing

- •Selecting Objects

- •Summary

- •Copying and Moving Objects

- •Resizing Commands

- •Using Construction Commands

- •Creating a Revision Cloud

- •Hiding Objects with a Wipeout

- •Double-Clicking to Edit Objects

- •Grips

- •Editing with the Properties Palette

- •Selection Filters

- •Groups

- •Summary

- •Working with Layers

- •Changing Object Color, Linetype, and Lineweight

- •Working with Linetype Scales

- •Importing Layers and Linetypes from Other Drawings

- •Matching Properties

- •Summary

- •Drawing-Level Information

- •Object-Level Information

- •Measurement Commands

- •AutoCAD’s Calculator

- •Summary

- •Creating Single-Line Text

- •Understanding Text Styles

- •Creating Multiline Text

- •Creating Tables

- •Inserting Fields

- •Managing Text

- •Finding Text in Your Drawing

- •Checking Your Spelling

- •Customizing the spelling dictionary

- •Summary

- •Working with Dimensions

- •Drawing Linear Dimensions

- •Drawing Aligned Dimensions

- •Creating Baseline and Continued Dimensions

- •Dimensioning Arcs and Circles

- •Dimensioning Angles

- •Creating Ordinate Dimensions

- •Drawing Leaders

- •Using Quick Dimension

- •Editing Dimensions

- •Summary

- •Understanding Dimension Styles

- •Defining a New Dimension Style

- •Changing Dimension Styles

- •Creating Geometric Tolerances

- •Summary

- •Creating and Editing Polylines

- •Drawing and Editing Splines

- •Creating Regions

- •Creating Boundaries

- •Creating Hatches

- •Creating and Editing Multilines

- •Creating Dlines

- •Using the SKETCH Command

- •Digitizing Drawings with the TABLET Command

- •Summary

- •Preparing a Drawing for Plotting or Printing

- •Creating a Layout in Paper Space

- •Working with Plot Styles

- •Plotting a Drawing

- •Summary

- •Combining Objects into Blocks

- •Inserting Blocks and Files into Drawings

- •Managing Blocks

- •Creating and Using Dynamic Blocks

- •Using Windows Features

- •Working with Attributes

- •Summary

- •Understanding External References

- •Editing an Xref within Your Drawing

- •Controlling Xref Display

- •Managing Xrefs

- •Summary

- •Preparing for Database Connectivity

- •Connecting to Your Database

- •Linking Data to Drawing Objects

- •Creating Labels

- •Querying with the Query Editor

- •Working with Query Files

- •Summary

- •Working with 3D Coordinates

- •Using Elevation and Thickness

- •Working with the User Coordinate System

- •Summary

- •Working with the Standard Viewpoints

- •Using DDVPOINT

- •Working with the Tripod and Compass

- •Displaying a Quick Plan View

- •Shading Your Drawing

- •Using 3D Orbit

- •Using Tiled Viewports

- •Defining a Perspective View

- •Laying Out 3D Drawings

- •Summary

- •Drawing Surfaces with 3DFACE

- •Drawing Surfaces with PFACE

- •Creating Polygon Meshes with 3DMESH

- •Drawing Standard 3D Shapes

- •Drawing a Revolved Surface

- •Drawing an Extruded Surface

- •Drawing Ruled Surfaces

- •Drawing Edge Surfaces

- •Summary

- •Drawing Standard Shapes

- •Creating Extruded Solids

- •Drawing Revolved Solids

- •Creating Complex Solids

- •Sectioning and Slicing Solids

- •Using Editing Commands in 3D

- •Editing Solids

- •Listing Solid Properties

- •Summary

- •Understanding Rendering

- •Creating Lights

- •Creating Scenes

- •Working with Materials

- •Using Backgrounds

- •Doing the Final Render

- •Summary

- •Accessing Drawing Components with the DesignCenter

- •Accessing Drawing Content with Tool Palettes

- •Setting Standards for Drawings

- •Organizing Your Drawings

- •Working with Sheet Sets

- •Maintaining Security

- •Keeping Track of Referenced Files

- •Handling Errors and Crashes

- •Managing Drawings from Prior Releases

- •Summary

- •Importing and Exporting Other File Formats

- •Working with Raster Images

- •Pasting, Linking, and Embedding Objects

- •Summary

- •Sending Drawings

- •Opening Drawings from the Web

- •Creating Object Hyperlinks

- •Publishing Drawings

- •Summary

- •Working with Customizable Files

- •Creating Keyboard Shortcuts for Commands

- •Customizing Toolbars

- •Customizing Tool Palettes

- •Summary

- •Creating Macros with Script Files

- •Creating Slide Shows

- •Creating Slide Libraries

- •Summary

- •Creating Linetypes

- •Creating Hatch Patterns

- •Summary

- •Creating Shapes

- •Creating Fonts

- •Summary

- •Working with the Customization File

- •Customizing a Menu

- •Summary

- •Introducing Visual LISP

- •Getting Help in Visual LISP

- •Working with AutoLISP Expressions

- •Using AutoLISP on the Command Line

- •Creating AutoLISP Files

- •Summary

- •Creating Variables

- •Working with AutoCAD Commands

- •Working with Lists

- •Setting Conditions

- •Managing Drawing Objects

- •Getting Input from the User

- •Putting on the Finishing Touches

- •Summary

- •Understanding Local and Global Variables

- •Working with Visual LISP ActiveX Functions

- •Debugging Code

- •Summary

- •Starting to Work with VBA

- •Writing VBA Code

- •Getting User Input

- •Creating Dialog Boxes

- •Modifying Objects

- •Debugging and Trapping Errors

- •Moving to Advanced Programming

- •Summary

- •A Final Word

- •Installing AutoCAD and AutoCAD LT

- •Configuring and Using Workspaces

- •Configuring AutoCAD

- •Starting AutoCAD Your Way

- •Configuring a Plotter

- •Discovering AutoCAD and AutoCAD LT

- •Accessing Technical Support

- •Autodesk User Groups

- •Internet Resources

- •System Requirements

- •Using the CD-ROM with Microsoft Windows

- •What’s on the CD-ROM

- •Troubleshooting

- •Index

Chapter 37 Programming with Visual Basic for Applications 1101

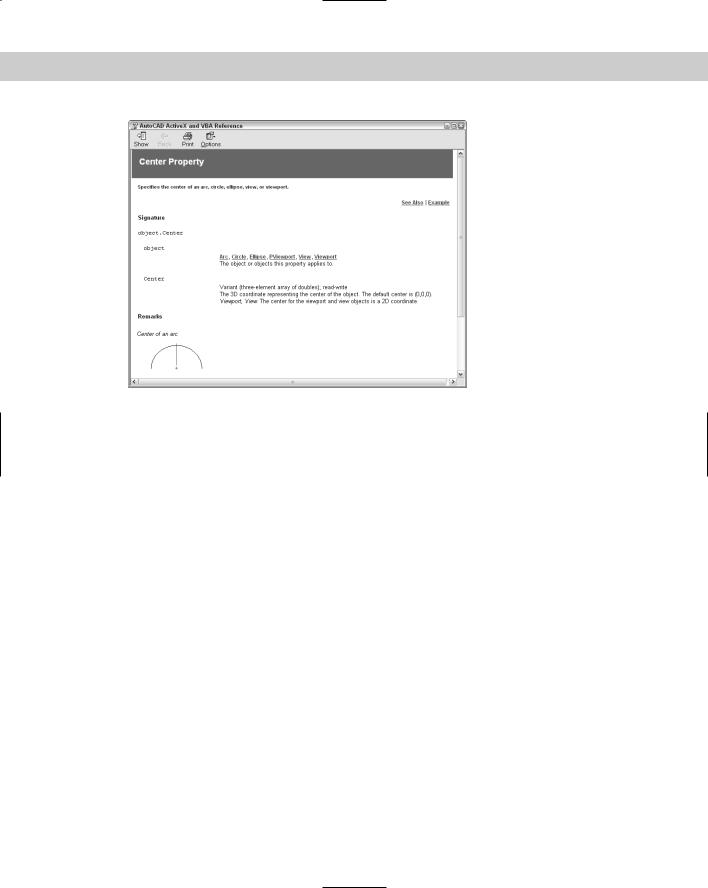

Figure 37-4: The help page for the Center Property.

After you open a help page, click Example to see an example. These examples are a great way to learn VBA. You can copy a snippet of VBA code and paste it into your own routine, and then edit it as you want.

For more general help, AutoCAD offers two systems:

The ActiveX and VBA Reference is an alphabetical listing of objects, methods, properties, and events.

The ActiveX and VBA Developer’s Guide explains ActiveX automation concepts and techniques.

To access these reference guides, switch to AutoCAD and choose Help Developer Help.

The Microsoft Visual Basic for Applications Help provides information on the general VBA environment. Click Help on the VBA IDE Menu Bar toolbar, or choose Help Microsoft Visual Basic Help. Here you see help for other VBA-enabled applications that you may have. You can use this when you’re ready to write VBA code that integrates more than one application.

After you start programming, you can get help on any expression by placing the cursor over it and pressing F1. For example, you can type AddLine and press F1 to access help on how to create a line.

Writing VBA Code

Now that you’re familiar with the structure of VBA objects, methods, and properties, you’re ready to start writing some code. As with any programming language, you need to learn syntax and understand variables and when to use them. Luckily, AutoCAD’s VBA Help includes many examples to guide you along the way. After you write some code, you can use it in AutoCAD.

Table 37-1 lists the various components of VBA code. This table defines various terms that you can often use when working with VBA.

1102 Part VII Programming AutoCAD

|

Table 37-1: Components of VBA Code |

|

|

Term |

Definition |

|

|

Procedure |

Code that does something and has a name. A procedure can be a subroutine, a function, |

|

or a property. |

Project |

A set of forms and modules. |

Module |

A set of subroutines, functions, and declarations that are usually related and comprise a |

|

distinct component in a project. A module can contain zero (0) or more procedures |

|

(subroutines and functions). |

Form |

A container for the visual components, such as buttons and text boxes, of a dialog box |

|

that you create for your VBA project. |

Subroutine |

A procedure, written in VBA code, that does not return a value. |

Function |

A procedure, written in VBA code, that returns a value. |

Property |

A procedure, written in VBA code, that specifies a value (the property of an object). |

Declaration |

One or more nonexecutable statements that name constants or variables and define |

|

their attributes (such as data type). |

Macro |

A public subroutine that a user can directly execute. |

|

|

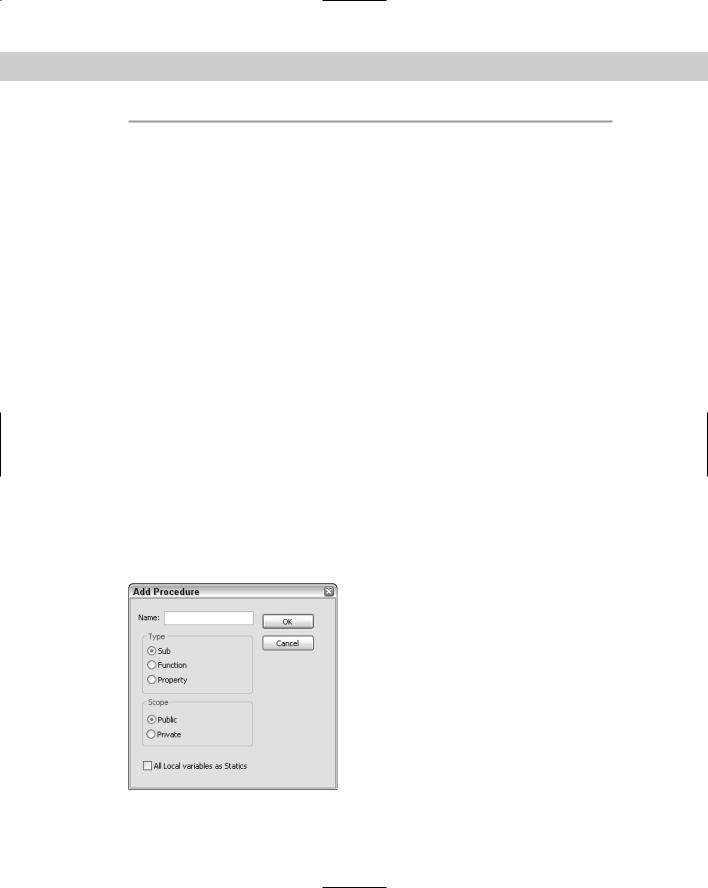

When you start to create code, VBA can create the basic structure for each procedure for you. Choose Insert Procedure (the Object Browser must be closed) to open the Add Procedure dialog box shown in Figure 37-5.

In the Name text box, type in a name for the new procedure, and then choose the type of procedure that you want to create. Choose whether you want the scope to be Public or Private and then click OK. If a subroutine (called sub for short) is declared Public, it is visible (can be called) from other modules or from the AutoCAD Macros dialog box. A sub that is declared Private is visible only within that module.

Figure 37-5: The Add Procedure dialog box.

Chapter 37 Programming with Visual Basic for Applications 1103

Note |

If you check the All Local Variables as Statics check box in the Add Procedure dialog box, your |

|

variables retain their values between the times that they’re used. |

Looking at VBA syntax

To start programming, you need an idea of how a VBA routine is put together. Here is a complete VBA routine that draws a 3D box.

‘Insert a 3D Solid Box Sub Box()

‘declare input variables to AddBox()

Dim dOrigin(0 To 2) As Double |

‘origin is array of doubles ‘(x,y,z) |

Dim dLength As Double |

‘length |

Dim dWidth As Double |

‘width |

Dim dHeight As Double |

‘height |

Dim myBox As Acad3DSolid |

‘holds return from AddBox() |

dOrigin(0) = 0# |

‘set origin to (0,0,0) |

dOrigin(1) = 0# |

|

dOrigin(2) = 0# |

|

dLength = 5# |

‘make a cube 5 by 5 by 5 |

dWidth = 5# |

|

dHeight = 5# |

|

‘create the box in modelspace of the current drawing

Set myBox = ThisDrawing.ModelSpace.AddBox(dOrigin, dLength, dWidth, dHeight)

‘change the viewpoint to better see the box ThisDrawing.SendCommand (“VPOINT 1,1,1 “)

End Sub

Here’s what the code means:

Line 1: Any text starting with an apostrophe (‘) is a comment. Placing comments in your routines helps you and others to understand what you’re doing.

Line 2: Sub indicates the start of a procedure, which is a named, unified piece of code. You can have several subroutines in a VBA project. A project is the file that you save, and it has a DVB file name extension. Each project contains the components of your subroutines, dialog boxes, and so on. The next word is the name of the subroutine. Within the parentheses, you can add arguments, if any. Use an empty set of parentheses if there are no arguments. Declaring variables is discussed later in this chapter.

Line 3: Another comment describing the next few lines of code. It’s always a good idea to comment your code, indicate what is happening, and even write notes to yourself to remind you of your intent.

Line 4: You can also declare variables using the Dim statement. Here dOrigin is used as the variable for the center of the box. (0 To 2) means that the origin will have three parts to it, for the X, Y, and Z coordinates. Double is a type of variable that is suitable for most coordinates. More about variable types later.

1104 Part VII Programming AutoCAD

Lines 5–7: Here you declare the dLength, dWidth, and dHeight variables, which will be used as the length, width, and height of the box. These are declared as type Double, which is also indicated by the d prefix on the variable names. This isn’t required, but it’s a good idea to use a naming scheme for variables to help remind you of their type, especially as you get deeper into programming or have to come back to some code after not seeing it for a while.

Line 8: Here you declare a variable called myBox as an Acad3DSolid to refer to the new box that will be created. Acad3DSolid is a data type that is specific to AutoCAD, and suitable for (you guessed it) referencing a 3D solid in your drawing. You can find other AutoCAD data types by looking in the Object Browser, or by looking at the Object Model as I explained earlier in this chapter.

Lines 9–11: Here you specify the X, Y, and Z coordinates of the origin of the box. The values are assigned to the dOrigin variable. The pound sign (#) is used to indicate a double-precision floating-point value. Use of the # sign is not required here but is more accurate and more clearly indicates your intentions. In some situations, rounding errors can occur when assigning numbers of one type to variables of another type, such as when you assign integers to doubles and doubles to integers.

Lines 12–14: Set the length, width, and height of the box to 5.

Line 15: Another comment.

Line 16: Finally, you’re ready to actually do something. The Set statement is used to set a variable to an object. Here you set the variable myBox to an Acad3DSolid defined by AddBox(dOrigin, dLength, dWidth, dHeight). The AddBox method creates a new 3D box. You need to define its origin, length, width, and height by using the variables that you’ve previously defined. The AddBox method is a member of ModelSpace, which is a member of ThisDrawing. You use ThisDrawing in VBA to access the current drawing. Because VBA within AutoCAD is automatically connected to AutoCAD, you don’t need to specify the application (that is, AutoCAD).

Line 17: Not another comment! Ask yourself these questions: If I looked at this code without the comments, would I have a harder time understanding it? What if there is a bug and I ask another programmer to find it? What if I am that programmer?

Line 18: Here we send the VPOINT command to change the viewpoint. Otherwise, the box that we just created will simply look like a square viewed from the top. The space after the numbers 1,1,1 and before the quotation mark is important; it signifies the end of the command. It’s like pressing the Enter key for this command.

Line 19: End Sub ends the subroutine.

To find the syntax for a statement that you want to use, look in VBA Help, as explained in the “Accessing help” section earlier in this chapter. In the preceding VBA routine, you might want to click AddBox and press F1 to find the syntax and elements that are required for creating a box. Then click Example to see an actual example of code for that statement.

Saving a VBA routine

As I mention earlier, the AutoCAD version of VBA saves VBA projects as separate files with a DVB file name extension. However, when you run a routine, AutoCAD lists it in the format ModuleName:Procedure Name. If your project has only one module, you can give the module and the procedure the same name. However, most VBA routines have more than one module, with one module controlling the rest. By running the controlling module, you run the whole project.

Chapter 37 Programming with Visual Basic for Applications 1105

To name a module, look in the Properties window. After you’ve created a module, the VBA IDE lists its name property as Module1 by default. Double-click Module1 and type a new name. Notice that the module name in the Project window also changes accordingly.

Note |

A module name (as well as the names of other forms and controls) must start with a letter, and |

|

can be up to 31 characters. Only letters, numbers, and the underscore character are allowed. |

To save a project as a separate file, which includes all of the modules, click Save on the VBA IDE Standard toolbar. VBA returns you to AutoCAD and opens the Save As dialog

box. Type a name for your project, choose a location, and click Save.

You can save your project in the Sample\VBA subfolder in the AutoCAD 2006 folder, or use another folder that is in AutoCAD’s support file search path.

Loading a VBA routine

Before you run a VBA routine, it must be loaded. If you’re working on the routine and want to run it to check how it works — which you’ll do often — you don’t need to load the routine. However, if you want to run a routine that hasn’t been opened, you need to use the VBALOAD command. When you choose Tools Macro Load Project (or type vbaload ), AutoCAD opens the Open VBA Project dialog box. Navigate to your project, choose it, and click Open. (AutoCAD asks you to confirm that you want to enable macros.) The project is now loaded.

Running a VBA routine

After you complete a subroutine, you can run it in AutoCAD. After all, that’s the reason for writing VBA code in the first place. To run a VBA routine, choose Tools Macro Macros (or type vbarun ). In the Macros dialog box, choose the module that you want to run and click Run.

AutoCAD runs the module, including other modules that may be controlled by the module that you run.

Using the Visual Basic Editor

When you type code from scratch in the Visual Basic Editor, you immediately notice that Visual Basic color-codes your text as you go. The most common colors are:

Normal text |

Black |

Syntax-error text |

Red |

Comments |

Green |

Keyword text |

Blue |

Keywords include variable types and other words that Visual Basic recognizes, such as Dim and Sub.

Tip |

You can customize these colors by choosing Tools Options from the Visual Basic menu and |

|

then choosing the Editor Format tab. Choose a type of text and then choose the desired color. |

|

Click OK. |

1106 Part VII Programming AutoCAD

When you start to type a keyword that Visual Basic recognizes, you’ll often see a box pop up that enables you to choose from a list, or that helps you to complete the word. The editor also adds or removes spaces, and capitalizes certain words for you to improve your syntax. If you make a syntax mistake, a small error message often appears as you work. In these ways, the Visual Basic Editor helps you to type accurate code.

STEPS: Creating, Saving, and Running a VBA Program

1.Open a new drawing using the acad.dwt template. Choose Tools Macro Visual Basic Editor.

2.Choose Insert Module. VBA opens the module text editor. (If you’ve previously opened a module, Visual Basic may launch with a blank module already open. In that case, skip this step.)

3.Choose Insert Procedure. In the Name text box, type DrawTorus. The type should be Sub and the scope should be Public. Click OK.

4.Type the following code. (Note that the second and last lines are already there for you.)

‘insert a Torus

Public Sub DrawTorus() ‘declare variables

Dim dCenter(0 To 2) As Double Dim dRadius1 As Double

Dim dRadius2 As Double

Dim myTorus As Acad3DSolid

‘set center of torus to 0,0,0 dCenter(0) = 0#

dCenter(1) = 0# dCenter(2) = 0#

dRadius1 |

= |

10# |

‘torus radius |

dRadius2 |

= |

2# |

‘tube radius |

‘insert the torus

Set myTorus = ThisDrawing.ModelSpace.AddTorus(dCenter, dRadius1, dRadius2)

‘set the viewpoint and shade it

ThisDrawing.SendCommand (“VPOINT 1,1,1 SHADEMODE GOURAUD “) End Sub

5.In the Properties window, change the name of the module to DrawTorus.

6.Because this routine is active, you don’t need to load it. Choose Save on the VBA IDE Standard toolbar. Save the project as ab37-01.dvb in your AutoCAD Bible folder.

7.Use the Windows task bar to return to your drawing. Choose Tools Macro Macros. In the Macro dialog box, choose DrawTorus and click Run. VBA draws and shades the torus.

Don’t save your drawing.

Chapter 37 Programming with Visual Basic for Applications 1107

Here’s an explanation of the routine that you just wrote and used. Note that blank lines are ignored.

Line 1: Comment describing routine.

Line 2: This is a public subroutine named DrawTorus with no parameters.

Line 3: Comment indicating which variable declarations are next.

Line 4: Declare the array to hold the X, Y, and Z coordinates for the center of the torus.

Line 5: Declare the variable to hold the radius of the torus.

Line 6: Declare the variable to hold the radius of the tube.

Line 7: Declare the variable to hold the created 3D object.

Line 8: Comment.

Lines 9–11: Set the center to 0,0,0.

Line 12: Set the torus radius to 10.0.

Line 13: Set the tube radius to 2.0.

Line 14: Comment.

Line 15: Create the torus.

Line 16: Comment.

Line 17: Send commands to AutoCAD to set the viewpoint and shade the torus for better viewing.

Line 18: End of subroutine.

Understanding variables

A variable holds a value for later use in your program. In VBA, you don’t need to explicitly declare your variables in advance (as long as you don’t include Option Explicit, which I explain later). You can use the Set statement to set a variable to an object, as in the example here. This statement creates a variable, cir, and sets its value equal to the circle that the AddCircle method creates.

Set cir = ThisDrawing.ModelSpace.AddCircle(cen, radius)

When you create a variable in this way, VBA assigns the default variant type to it. The variant type of variable can contain numbers, dates, or strings (of text).

However, declaring variables explicitly in advance has two advantages:

You can specify the type of variable, which usually uses less memory than the default variant type.

As you continue to enter code, VBA checks the variable’s spelling for you, thus reducing the chance for errors.

You declare variables using the Dim statement. Here’s an example:

Dim radius As Double

1108 Part VII Programming AutoCAD

You can create three different levels of variables:

A Public variable is available to all procedures in the project. It is shown as follows:

Public dRadius As Double

A module-level variable is available to all of the procedures in the module. You create a module-level variable by placing the declaration (with the Dim statement) at the top of a module, in a Declarations section. Another way to create a module-level variable is to use the Private statement. Examples are shown here:

Dim dNum3 as Double Private dNum2 as Double

A procedure-level variable is used only within a procedure. You can place the variable anywhere within the procedure, as long as you declare the variable before you use it.

Placing the statement Option Explicit in a Declarations section requires all variables to be declared. Using Option Explicit is a way to force yourself to write your code more carefully. Declared variables are easier to debug because they’re easier to find.

Table 37-2 describes the kinds of variables that you can declare.

|

Table 37-2: VBA Variable Types |

|

|

Variable |

Description |

|

|

Boolean |

For variables that can have only two values — True or False. |

Byte |

Positive integers from 0 to 255. |

Integer |

Integers from –32,768 to +32,767. |

Long |

Integers from –2,147,483,648 to +2,147,483,647. |

Currency |

Values from –922,337,203,685,477.5808 to +922,337,203,685,477.5807. Use this variable |

|

for currency or for other values that need accuracy to several decimals. |

Single |

Single-precision floating-point values. Single variables use less memory than double |

|

variables, but their values are limited. |

Double |

Double-precision floating-point values. Double variables offer much greater precision |

|

than single variables. Most coordinates use this variable type. Three double variables |

|

create the X, Y, and Z values. |

Date |

Holds dates and times that are stored as real numbers. The number to the left of the |

|

decimal is the date, and the number to the right of the decimal is the time. |

String |

Fixedor variable-length text strings, including letters, numbers, spaces, and punctuation |

|

characters. |

Object |

Objects such as an application, a drawing, or a drawing object. |

Variant |

Contains numbers, dates, or strings. When you don’t declare a type for a variable, VBA |

|

uses this type by default. |

|

|

Chapter 37 Programming with Visual Basic for Applications 1109

Here’s an example that uses the Date variable type and displays it in a message box:

Sub DateDemo() |

|

|

|

Dim dt |

As Date |

|

|

Dim dbl |

As Double |

|

|

dt |

= Now |

‘set the dt to the current |

date and time |

dbl |

= dt |

‘assign this date value to |

a double |

MsgBox “Normal date version: “ & dt & “ Double version: “ & dbl End Sub

Running DateDemo (by pressing F5) would show something similar to:

Normal date version: 5/10/2005 8:03:13 PM

Double version: 38482.8355671296

Creating VBA statements

Although a complete discussion of how to write VBA code is beyond the scope of this book, some general principles will be helpful.

A statement in VBA is the most basic unit of code. It contains a complete instruction. There are three kinds of statements:

A declaration names a variable, constant, or procedure, as in this example:

Dim dOrigin as Double

An assignment assigns a value to a variable or constant. For example: dOrigin = 0#

An executable creates an action. For example, it can execute a method or function, or create a loop or branch that acts on a block of code, as shown here:

Set myBox = ThisDrawing.ModelSpace.AddBox(dOrigin, dLength, dWidth, dHeight)

VBA has many keywords, functions, and other components that you can use to create code. To find the basic components of the VBA language, choose Help Microsoft Visual Basic Help. From the Contents tab, double-click Visual Basic Language Reference, which lists terms that are part and parcel of VBA. Here are some examples:

Constants: Constants can be used anywhere in your code to provide a named value. For example, VBA offers color and date constants that you can use to specify colors and dates.

Functions: VBA includes many functions that you’ll find familiar if you’ve used AutoLISP. For example, the ABS function returns the absolute value (without a plus or minus sign) of any number. The DATE function returns the current system date.

Keywords: Keywords are words that have a special meaning in VBA. They are often used as parts of VBA statements. For example, Else is a keyword that is used in the If...Then...Else statement. You’re already familiar with the Set keyword, which is used in the Set statement.