Text III. Baroque buildings: architecture in motion

Symmetrical, clearly articulated buildings with harmoniously proportioned interiors and facades were the declared goal of the architects of the Renaissance. The architects of the Baroque, by contrast, no longer believed in the equal status of individual elements, but emphasized the effect of the whole. Art in the period between 1580 and 1770 was summed up in the word Baroque. At this time the Catholic Church was the most important patron, and as a result it was church building which advanced the Baroque style to the greatest extent. In the wake of the Reformation, which Martin Luther's Theses had initiated in 1517, the Catholic Church was called into question. Now the Church wanted to strengthen its role in society once again, in addition representing itself through architecture. As a result churches and monasteries arose in the Catholic countries of Europe whose aim was to convince the faithful of the importance of the Church.

The Baroque style began in Rome. It was there, towards the end of the sixteenth century, that modernizing urban planning reached its peak: whole streets were laid out and the Vatican was incorporated architecturally into the city. The newly built St. Peter's Basilica, the most important church in Christendom, inaugurated a major project in Rome at the beginning of the century.

Over the long period of its construction this project went through many changes of plan and architect, finally becoming one of the most striking examples of Baroque architecture.

When the new building started under Pope Julius II in 1506, a building on a central plan was mapped out which architects carried out over the following decades. Forty years later, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) surmounted the church with a massive dome. Two elements determine its external impact: the repeating motif of paired columns and, set back from them, the straight-headed, pedimented windows. These forms alternate below the monumental dome, which seems to be put in motion through this variation. On the dome, too, Michelangelo created optical depth and relief: across its shell, ribs radiate forth like light rays from the dome's lantern. Between them are set more windows, which pursue the pediment motif of the drum. By repeating individual elements, but varying them, Michelangelo played with the effect of nearness and distance, here too creating the impression of movement in spite of the heaviness of the dome.

By 1590 the centrally planned building was finally finished according to plan, but the project of St. Peter's was nonetheless a long way from completion. Baroque architect Carlo Maderno* was given the task of continuing the work. At the beginning of the seventeenth century he was required to add a nave to the central ground-plan. In the Baroque period the directional nave structure was once again acquiring more supporters: not only did it offer more space, but with its basic form of a cross it also came closer to the architectural task of a Christian church. When St. Peter's nave was finished in 1626, however, the building was no longer convincing in its effect: the dome had lost its monumentality, and by contrast the facade looked too wide for its height. In order to return once again to the originally planned effect, it was decided to redesign the entire square in front of the church. Gian Lorenzo Bernini* created an oval square that demonstrates the whole sense of movement of the Italian Baroque. Wide colonnades embrace the square like two arms and emphasize the momentum of the site created by open and closed forms. In addition Bernini lent the architecture an upward movement optically by increasing the height of the colonnades around the square as they approach the church. Dynamism, momentum, animation: these central characteristics of Baroque architecture are not only employed in the project of St. Peter's Basilica. The dynamic formal language typical of the Baroque can also be seen in many other of the numerous new churches and church rebuildings of the period. One of them is the church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale in Rome, also designed by Bernini.

|

|

|

The form of its ground-plan is new and would be used again and again during the Baroque period. The church is based on a transverse oval and this form recurs many times in the body of the building.

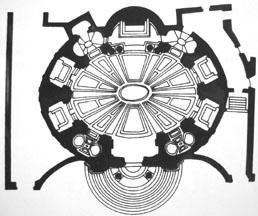

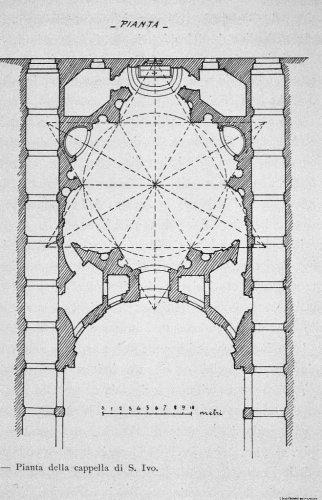

Thus the dome too has a basic oval form and as a result the drum leading to it is also oval in shape. The curved forms continue on the outside of the building: curved steps lead up to the entrance, which is enclosed by a round roof. Even the walls adjoining the portal take part in the movement, as they are curved and jut out some distance. And it was not only the facades of Baroque buildings that seemed to move and pulsate in concave and convex curves. The ground-plans too occasionally contribute to the dynamic effect: the footprint of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, the church of the University of Rome, is a six-pointed star whose differently shaped points create an optical interplay.

Francesco Borromini* began work on the new building in 1642 and the project was to continue for over 20 years. The resulting interior is a space which seems to curve forwards and back. This impression is created in Sant'Ivo by the ends of the star-shaped ground-plan: they are extended alternately either into niches which are rounded on the outside or into enclosures which curve inwards on the inside.

Decoration, in the interior as well as on the facade, was thus an important component of Baroque architecture. On the facades of Baroque buildings, architectural ornamentation provided effects of light and shadow and thus contributed to the impression of movement. In the interiors too in churches as in secular buildings decoration knew no limits. Ceilings and walls disappeared behind stucco ornament and painting, and magnificent marble fittings, columns with richly ornamented capitals, or lavishly designed floors completed the splendid overall effect. Even the fittings of Baroque churches were designed for effect: the interior with its marble, gold, and rich figurative decoration became more and more complex, as illusionistic wall and ceiling paintings contributed further to lending the spaces volume and depth. Frequently this was more appearance than reality: marble was frequently used merely as a veneer and columns were in reality made of brick; mirrors gave a false sense of size which a small room could certainly not compete with; or domes which looked magnificent on the outside were constructed with a simple wooden framework on the inside. Sometimes the perspectivally correct painted architecture looked like a continuation of what had actually been built. This is shown in the ceiling fresco of the church of Sant'Ignazio in Rome, which was painted in the 1690s.

The painter Andrea Pozzo* fused architecture and painting together on the ceiling of the church. His columns and arches painted in the vault of the ceiling look real at first sight and form a continuation of the actual architecture one story higher. The illusionistic architecture fulfills its purpose and provides the illusion of a wide space filled with movement. Painting and architecture come together to trick the viewer's perception through stylized illusionism. This trend was not limited to sacred architecture any more than the wealth of forms or opulence: secular buildings from the Baroque period, such as palaces or city residences, were no less magnificent in their appearance.

Notes:

Carlo Maderno- Карло Мадерна (1556-1629 года) Итальянский архитектор, работал в Риме, считается основателем стиля раннего барокко в архитектуре.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini - Джан Лоренцо Бернини (1598—1680) — великий итальянский архитекторискульптор, крупнейший представитель римского и всего итальянскогобарокко.

Francesco Borromini - Франческо Борромини (1599—1667) — великийитальянскийархитектор, работавший вРиме. Наиболее радикальный представитель раннегобарокко.

Andrea Pozzo - Андреа дель Поццо (1642—1709) — итальянскийживописециархитектор. Представительбарокко. Виртуозный мастериллюзионистическойросписи (фрески в церквиСант-ИньяциовРиме, 1685-99 гг.). Автор трактата по теорииперспективы.