ГОС_1 / Теор. фонетика

.pdfIn addition to the cases listed above, we can recall old information by using words,

which in a different context, would present new information. Such lexical items are deaccented, and the de-accenting tells us that the lexical items are being used anaphorically [Kreidler 1997: 170]. There are several kinds of lexical anaphora:

1.Repetition, e.g. I've got a job, / but I don't like the job.

2.How many times ? Three times.

3.Synonyms, e.g. Maybe this man can give us directions. I'll ask the fellow. (the fellow = the man)

4.Superordinate terms, e.g. Didyou enjoy Blue Highways ? I haven't read the book

(Blue Highways = the book).

This wrench is no good. I need a bigger tool, (wrench = tool)

The purpose of de-accenting in this case is to relate the more general term - the book and tool, in these examples, to the more specific term of the preceding sentence. But the de-accented word or term does not necessarily refer directly to a previous term, e.g.

That's a nice looking cake. Have a piece.

But it must be de-accented.

De-accenting also occurs when a word is repeated, even though it has a different referent the second time, e.g.

a room with a view and without a view, deeds and misdeeds, written and unwritten.

De-accenting can be used for a very subtle form of communication – to embed an additional meaning,

e.g. What did you say to Roger? I didn't speak to the idiot.

The last sentence actually conveys two meanings, one embedded in the other: I didn't speak to Roger', and I call Roger an idiot'. De-accenting the idiot is equivalent to say- ing: the referent for this phrase is the same as the last noun that fits.

In sum, sentence stress/utterance-level stress helps the speaker emphasize the most significant information in his or her message.

3. Rhythm

We cannot fully describe English intonation without reference to speech rhythm. Prosodic components (pitch, loudness, tempo) and speech rhythm work, interdependently. Rhythm seems to be a kind of framework of speech organization. Linguists sometimes consider rhythm as one of the components of intonation. D.Crystal, for instance, views rhythmicality as one of the constituents of prosodic systems [Crystal 1969].

Rhythm as a linguistic notion is realized in lexical, syntactical and prosodic means and mostly in their combinations. For instance, such figures of speech as sound or word repetition, syntactical parallelism, intensification and others are perceived as rhythmical on the lexical, syntactical and prosodic levels.

In speech, the type of rhythm depends on the language. Linguists divide languages into two groups: syllable-timed like French, Spanish and other Romance languages and stress-timed languages, such as Germanic languages English and German, as well as Ukrainian. In a syllable-timed language the speaker gives an approximately equal amount of time to each syllable, whether the syllable is stressed or unstressed and this produces the effect of even rather staccato rhythm.

In a stress-timed language, of which English is a good example, the rhythm is based on a larger unit than syllable. Though the amount of time given on each syllable varies considerably, the total time of uttering each rhythmic unit is practically un changed. The stressed syllables of a rhythmic unit form peaks of prominence. They tend

101

to be pronounced at regular intervals no matter how many unstressed syllables are located between every two stressed ones. Thus the distribution of time within the rhythmic unit is unequal. The regularity is provided by the strong "beats".

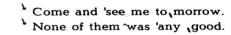

Speech rhythm has the immediate influence on vowel reduction and elision. Form words such as prepositions, conjunctions as well as auxiliary and modal verbs, personal and possessive pronouns are usually unstressed and pronounced in their weak forms with reduced or even elided vowels to secure equal intervals between the stressed syllables, e.g..

The markedly regular stress-timed pulses of speech seem to create the strict, abrupt and spiky effect of English rhythm. The English language is an analytical one. This factor explains the presence of a considerable number of monosyllabic form words which are normally unstressed in a stretch of English speech. To bring the meaning of the utterance to the listener the stressed syllables of the notional words are given more prominence by the speaker and the unstressed monosyllabic form words are left very weak. It is often reflected in the spelling norm in the conversational style, e.g.

I'm sure you mustn't refuse him.

Speech rhythm is traditionally defined as recurrence of stressed syllables at more or less equal intervals of time in a speech continuum. We also find a more detailed defi- nition of speech rhythm as the regular alternation of acceleration and slowing down, of relaxation and intensification, of length and brevity, of similar and dissimilar elements within a speech event. In the present-day linguistics rhythm is analysed as a system of similar adequate elements. A.M. Antipova [1984] defines rhythm as a complex language

system which is formed by the interrelation of lexical, syntactic and prosodic means.

It has long been believed that the basic rhythmic unit is a rhythmic group, a speech segment which contains a stressed syllable with preceding or/and following unstressed syllables attached to it. Another point of view is that a rhythmic group is one or more words closely connected by sense and grammar, but containing only strongly stressed syllable and being pronounced in one breath, e.g. Thank you→ The stressed syllable is

the prosodic nucleus of the rhythmic group. The initial unstressed syllables preceding the nucleus are called proclitics, those following the nucleus are called enclitics, e.g.:

The 'doctor 'says it’s not quite serious = 1 intonation group [4 rhythmic groups]

Table 21

ðə 'dɔktə |

'sez its |

'nɔt kwait |

siə.ri. əs |

1st rhythmic |

2nd rhythmic |

3rd rhythmic |

4th rhythmic |

group |

group |

group |

group |

proclitics |

enclitics |

enclitics |

enclitics |

In qualifying the unstressed syllables located between the stressed ones there are two main alternative views among the phoneticians. According to the so-called semantic viewpoint the unstressed syllables tend to be drawn towards the stressed syllable of the same word or to the lexical unit according to their semantic connection, concord with other words, e.g.

Negro Harlem | became | the largest | colony | of coloured people.

According to the other viewpoint the unstressed syllables in between the stressed ones tend to join the preceding stressed syllable. It is the so-called enclitic tendency. Then the above-mentioned phrase will be divided into rhythmical groups as follows, e.g.

Negro Harlem | became the | largest | colony of | coloured people.

102

To acquire a good English speech rhythm the learner should: 1) arrange sentences into intonation groups and 2) then into rhythmic groups 3) link every word beginning with a vowel to the preceding word 4) weaken unstressed words and syllables and reduce vowels in them 5) make the stressed syllables occur regularly at equal periods of time.

Maintaining a regular beat from stressed syllable to stressed syllable and reducing intervening unstressed syllables can be very difficult for Ukrainian and Russian learners English. Their typical mistake is not giving sufficient stress to the content words and not sufficiently reducing unstressed syllables. Giving all syllables equal stress and the lack of selective stress on key/content words actually hinders native speakers' comprehension.

The rhythm-unit break is often indeterminate. It may well be said that the speech tempo and style often regulate the division into rhythmic groups. The enclitic tendency is more typical for informal speech whereas the semantic tendency prevails in accurate, more explicit speech.

The more organized the speech is the more rhythmical it appears, poetry being the most extreme example of this. Prose read aloud or delivered in the form of a lecture is more rhythmic than colloquial speech. On the other hand rhythm is also individual – a fluent speaker may sound more rhythmical than a person searching for the right word and refining the structure of his phrase while actually pronouncing it.

However, it is fair to mention here that absolutely regular speech produces the effect of monotony.

The most frequent type of a rhythmic group includes 2-4 syllables, one of them stressed, others unstressed. In phonetic literature we find a great variety of terms defining the basic rhythmic unit, such as an accentual group or a stress group which is a speech segment including a stressed syllable with or without unstressed syllables attached to it; a pause group – a group of words between two pauses, or breath group – which can be uttered within a single breath. As you have probably noticed, the criteria for the defini- tion of these units are limited by physiological factors. The term "rhythmic group" used by most of the linguists [see Lehiste 1973; Gimson 1981; Антипова 1984] implies more than a stressed group or breath group. I.V. Zlatoustova [1979] terms it "rhythmic structure". Most rhythmic groups are simultaneously sense units. A rhythmic group may comprise a whole phrase, like "I can't do it" or just one word: "Unfortunately..." or even a one-syllable word: Well...; Now.... So a syllable is sometimes taken for a minimal rhythmic unit when it comes into play.

We undoubtedly observe the most striking rhythmicality in poetry. In verse the similarity of rhythmical units is certainly strengthened by the metre, which is some strict number and sequence of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line. Strict alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables in metric versification allows us to regard a syllable as the minimal rhythmic unit in metric verse. Then again comes a rhythmic group, an intonation group, a line, a stanza. They all form the hierarchy of rhythmic units in poetry. English verse is marked by a descending bow-shaped melody contour, decentralized stress organization. The strict recurrence of such intonation patterns secures a stable periodicity in verse rhythm. The basic rhythm unit in verse, however, is a line. On the prosodic level the rhythm in a line is secured by the similar number of syllables, their temporal similarity, descending melody contour, tone and intensity maximum at the be- ginning, tone and intensity minimum at the end and the final pause. These parameters

make the line a stable rhythmic unit.

Phonetic devices add considerably to the musical quality a poem has when it is read aloud.

1.First and foremost among the sound devices is the rhyme at line endings. Most skilful rhyming is sometimes presented by internal rhyme with two rhyming words within a single line.

2.Assonance occurs when a poet introduces imperfect rhymes often employed deliberately to avoid the jingling sound of a too insistent rhyme pattern, e.g. "stone" is made to rhyme with "one"; "youth" is rhymed with "roof". In this way the rhymes do not fall into a sing-song pattern and the lines flow easily.

103

3.Alliteration is the repetition of the same sound at frequent intervals.

4.Sound symbolism (imitation of the sounds of animals) makes the description very

vivid.

Structural or syntactical stylistic devices indicate the way the whole poem has

been built, thus helping the rhythm to fulfil its constitutive function.

1.Repetition. Poets often repeat single lines or words at intervals to emphasize a particular idea. Repetition is to be found -in poetry which is aiming at special musical effects or when a poet wants us to pay very close attention to something.

2.Syntactical parallelism helps to increase rhythmicality.

3.Inversion, the unusual word order specially chosen to emphasize the logical centre of the phrase.

4.Polysyndeton is a syntactical stylistic device which actually stimulates rhythmicality of a poem by the repetition of phrases or intonation groups beginning with the same conjunctions "and" or "or".

Semantic stylistic devices impart high artistic and aesthetic value to any work of art including poetry.

1.Simile is a direct comparison which can be recognized by the use of the words, "like" and "as".

2.Metaphor is a stylistic figure of speech which is rather like simile, except that the comparison is not direct but implied and that makes the effect more striking.

3.Intensification is a special choice of words to show the increase of feelings, emotions or actions.

4.Personification occurs when inanimate objects are given a human form or human feelings or actions.

Our further point should concern prose. We would like to start with a fairy-tale which is nearest to poetry and could be considered an intermediate stage between poetry and prose as it is famous for its obvious rhythmicality and poetic beauty.

A fairy-tale has a specific manner of oral presentation, different from any other sort of text. The reading of a fairy-tale produces a very strong impression on the listener. The prosodic organization of a fairy-tale creates the effect of euphony which implies sound harmony, melodiousness, measured steps of epic character of phonation. The most functional features of euphony are rhythmicality and the melody component of intonation.

The rhythm of a fairy-tale is created by the alternations of commensurate tone, loudness and tempo characteristics of intonation [O’Connor 1977]. Intonation groups are marked by similarity of tone contour and tempo in the head and the nuclear tone. Rhythmicality is often traced in alternations of greater and smaller syllable durations.

The fairy-tale narration is marked by the descending or level tone contour in the head of intonation groups and specific compound nuclear tones: level-falling, level-rising, falling-level, rising-level. The level segment of nuclear tones adds to the effect of slowing down the fairy-tale narration and its melodiousness.

The reading or reciting of a fairy-tale is not utterly monotonous. Alongside with the even measured flow of fairy-tale narration we find contrastive data in prosodic pa- rameters which help to create vivid images of fairy-tale characters and their actions. For example, with respect to medium parameters high/low pitch level is predominant in describing the size of a fairy-tale character (huge bear – little bear); fast/slow tempo strengthens the effect of fast or slow movements and other actions. Splashes of tone on such words of intensification as: all, so, such, just, very make for attracting the listener's attention. Deliberately strict rhythm serves as a means of creating the image of action dynamism so typical of fairy-tales.

Now we shall turn to the oral text units which form the hierarchy of rhythm structure in prose. Rhythmic groups blend together into intonation groups which correspond to the smallest semantic text unit — syntagm. The intonation group reveals the similarity of the following features: the tone maximum of the beginning of the intonation group, loudness maximum, the lengthening of the first rhythmic group in comparison with the following one, the descending character of the melody, often a bow-shaped melody con-

104

tour. An intonation group includes from 1 to 4 stressed syllables. Most of intonation groups last 1-2 seconds. The end of the intonation group is characterized by the tone and loudness minimum, the lengthening of the last rhythmic group in it, by the falling terminal tone and a short pause.

The similarity of the prosodic organization of the intonation group allows us to count it as a rhythmic unit. The next text unit is undoubtedly the phrase. A phrase often coincides either with an intonation group or even with the phonopassage. In both those cases a phrase is perceived as a rhythmic unit having all the parameters of either an intonation group, or a phonopassage.

In prose an intonation group, a phrase and a phonopassage seem to have similar prosodic organization:

1.the beginning of a rhythmic unit is characterized by the tone and intensity maximum, the slowing of the tempo;

2.the end of a rhythmic unit is marked by a pause of different length, the tone and intensity minimum, slowing of the tempo, generally sloping descending terminal tones;

3.the most common prenuclear pattern of a rhythmic unit is usually the High

(Medium) Level Head.

The prosodic markers of rhythmic units differ in number. The intonation group has the maximum of the prosodic features constituting its rhythm. The phonopassage and the rhythmic group are characterized by the minimum of prosodic features, being mostly marked by the temporal similarity.

It should be also noted that there are many factors which can disrupt the potential rhythm of a phrase. The speaker may pause at some points in the utterance, he may be interrupted, he may make false starts, repeat a word, correct himself and allow other hesitation phenomena.

Spontaneous dialogic informal discourse reveals a rich variety of rhythm organization and the change of rhythmic patterns within a single stretch of speech. The most stable regularity is observed on the level of rhythmic and intonation groups. They often coincide and tend to be short. The brevity of remarks in spontaneous speech explains the most common use of level heads of all ranges, abrupt terminal tones of both directions. The falling terminal tone seems to be the main factor of rhythmicality in spontaneous speech. Longer intonation groups display a great variety of intonation patterns including all kinds of heads and terminal tones. The choice of the intonation pattern by the participants of the conversation depends on their relationship to each other, the subject matter they are discussing, the emotional state of the participants and other situational factors. As a result informal spontaneous conversation sounds very lively and lacks monotony.

The experimental investigations carried out in recent researches give ground to postulate the differences in the prosodic organization of prosaic and poetic rhythm:

1.In verse there are simple contours often with the stepping head, the falling nuclear tone is more often gently sloping; there is a stable tendency towards a monotone.

2.In verse the stressed syllables are stronger marked out by their intensity and duration than in prose.

3.In verse the tempo is comparatively slower than in prose.

4.In verse the rhythmic units except the rhythmic group tend to be more isochronous than in prose. The rhythmic group presents an exception in this tendency of verse.

The ability to process, segment, and decode speech depends not only on the listener's knowledge of lexicon and grammar but also on being able to exploit knowledge of the phonetic means. It has been proved that the incoming stream of speech is not decoded on the word level alone. Having analyzed a corpus of 'mishearings' committed by native English speakers in everyday conversation, scholars have discovered the following four strategies (holding the stream of speech in short-term memory) which the speakers employ to process incoming speech [see: Celce-Murcia et al 1996: 222]:

1.Listeners attend to stress and intonation and construct a metrical template

– a distinctive pattern of strongly and weakly stressed syllables - to fit the

105

utterance.

2.They attend to stressed vowels. (It should be noted, however, that errors involving the perception of the stressed vowels are rare among native speakers).

3.They segment the incoming stream of speech and find words that correspond to the stressed vowels and their adjacent consonants.

4.They seek a phrase – with grammar and meaning - compatible with the metrical template identified in the first strategy and the words identified in the third strategy.

All four strategies are carried out simultaneously. In addition to carrying out these

strategies, listeners are also calling up their prior knowledge, or schemata (higher-order mental frameworks that organize and store knowledge), to help them make sense of the bits and pieces of information they perceive and identify using these strategies [Gilbert 1983; Celce-Murcia et al 1996: 223]

These exemplified strategies suggest that in decoding speech listeners perform the following processes related to pronunciation:

1.discerning intonation units;

2.recognizing stressed elements;

3.interpreting unstressed elements;

4.determining the full forms underlying reduced speech.

One of the most important realizations that contributes to successful speech processing is that spoken English is divided into chunks of talk = intonation units (also referred to as thought groups or prosodic phrases). In spoken English there are five signals that can mark the end of one intonation unit and the beginning of another [Celce-Murcia et al 1996: 226]:

1.A unified pitch contour.

2.A lengthening of the unit-final stressed syllable.

3.A pause.

4.A reset of pitch.

5.An acceleration in producing the unit-initial syllable(s).

Successful identification of the metrical template is based on the identification of the prominent elements in a thought group.

In their overview of phonology and discourse, Celce-Murcia and Olshtain [2000:3045] emphasize the following important functions of prosody in oral discourse:

1.the information management function;

2.the interactional management function, and

3.the social functions of intonation.

Now we will discuss these functions in brief and outline their importance for inter-

cultural verbal interactions.

It is generally claimed that phonology performs two related intonation management actions in English and in other languages:

1.it allows the speaker to segment intonation into meaningful word-groups;

2.it helps the speaker signal new or important information versus old and less

important information [Celce-Murcia, Olshtain 2000: 36].

In English the speakers usually resort to the following prosodic clues to segment their speech into meaningful word groups:

1. They make a pause at the end of a meaningful word group, 2) deploy a change in speech and 3) lengthen the last stressed syllable [Gilbert 1983]. These clues enable them to organize information into chunks. Consider the following examples to illustrate this function prosody, in which the same words with different prosody express very different meanings Celce-Murcia, Olshtain 2000: 37]:

Have you met my brother Fred? Have you met my brother, Fred?

'Father, " said Mother, "is late" Father said, "Mother is late ".

At the discourse level the speaker should aim at appropriate prosodic segmentation and avoid misinterpretation or confusion on the part of the listener.

106

The other important information management function of prosody is marking new versus old information. It should be noted that new information typically occurs at the end the utterance. In these examples [taken from: Celce-Murcia and Olshtain 2000:38], whatever information is new tends to receive special prosodic attention: the word is stressed d the pitch changes (such syllables are printed in capital letters):

A. SI Can I HELP you? |

B. SI I've lost an umBRELla. |

|

|

S2 YES, please. I'm looking for a |

S2 A Lady's umbrella. |

|

|

BLAzer. |

SI YES. One with STARS on it. |

|

|

SI Something CAsual? |

GREEN stars. |

|

|

S2 Yes, something casual in WOOL. |

|

|

|

Interaction management function of prosody includes moves involving contrast, correction / repair, and contradiction [ibid.47]. The speakers signal contrast using prosodic cues (strong stress, high pitch) when they want to shift the focus of attention or create a contrast where there was none before [ibid: 38] as in the example that follows:

S1 I'd like APples, please.

S2 Would you like the YELlow ones or the RED ones?

When contradictions or disagreements arise in oral discourse, the speakers apply prosodic clues to shift the focus from one constituent to another, e.g.:

S1 It's HOT.

S2 It's NOT hot

S1 It IS hot.

S2 Come on, it's not THAT hot.

The speakers actively use prosodic means while self-correcting or correcting their interlocutors in the process of conversation during the so-called repair. This example of

interactional management function is very similar to disagreement from a prosodic point of view, e.g.:

S1 You speak GERman, DON'tyou?

S2 Not GERman, FRENCH.

The examples given above illustrate how English speakers use prosody for informational management and interactional management.

Phonetic and phonological problems of discourse still require a point-by-point and systemic study.

References

1.Антипова А.М. Ритмическая система английской речи. – М., 1984.

2.Златоустова Л.В. О ритмических структурах в поэтических и прозаических текстах // Звуковой строй языка. – М., 1979.

3.Николаева Т.М. Фразовая интонация славянских языков. – М., 1977.

4.ПаращукВ.Ю.Теоретичнафонетикаанглійськоїмови:Навчальнийпосібник для студентів факультетів іноземних мов. – В.Ю. Паращук Тема “Ukrainian Accent of English” написана В.Ю. Кочубей. – Вінниця, НОВА КНИГА, 2005.

– 240с.

5.Теоретическая фонетика английского языка: Учебник для студентов инсти- тутов и факультетов иностранных языков/ М.А. Соколова, К.П. Гинтовт,

107

И.С. Тихонова, Р.М. Тихонова. – М.: Гуманитарный издательский центр ВЛАДОС, 1996. – 266с.

6.Цеплитис Л.К. Анализ речевой интонации. – Рига, 1974.

7.Черемисина Н.В. К проблеме взаимосвязи гармонии и интонации в русской художественной речи // Синтаксис и интонация. – Уфа, 1973.

8.Bolinger D. Intonation. – London, 1972.

9.Celce-Murcia M., Brinton D., Goodwin J. Teaching Pronunciation: A Reference for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. – 428p.

10.Celce-Murcia M., Olshtain E. Discourse and Context in Language Teaching: a Guide for Language Teachers. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

– 279p.

11.Crystal D. Prosodic Systems and Intonation in English. – Cambridge, 1969.

12.Fries Ch. Linguistics and Reading. – New York, 1965.

13.Gilbert J.B. Pronunciation and Listening Comprehension // Cross Currents. – No. 10 (1). – 1983. – P. 53-61.

14.Gimson A.C. An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English. – London, 1981.

15.Halliday M. Course of Spoken English Intonation. – London, 1970.

16.Kingdon R. The Groundwork of English Intonation. – London, 1958.

17.Kreidler W. Describing Spoken English: An Introduction. – London and New York: Routledge, 1997. – P. 144-154.

18.Lehiste I. Rhythmic Units and Syntactic Units in Production and Perception. – Oxford, 1973.

19.O’Connor J.D. Phonetics. – Penguin, 1977.

20.Peddington M. Phonology in English Language Teaching: An International Approach. – London and New York: Longman, 1996.

21.Pike K. The Intonation of American English. – New York, 1958.

22.Roach P. English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. – P. 133-178.

Questions

1.Define prosody.

2.Define intonation pattern.

3.What is nucleus? What other synonymic terms do you know?

4.What tones are called kinetic or moving? How do they differ from static tones?

5.Characterize each of the nuclear tones in English. What are their meanings? What do they express?

6.Characterize the level nuclear tone.

7.What are the components of the intonation pattern in English?

8.What are the types of pre-nucleus?

9.What pitch ranges are distinguished?

10.What pitch levels are there in English?

11.Define the tempo of speech.

12.What kind of pauses are there in English?

13.What methods for recording intonation patterns in writing do you know? Characterize each of them.

14.What functions of intonation are distinguished by D. Crystal, P. Roach?

15.How is the communicative function of intonation realized?

16.Define logical sentence stress.

17.What are the terms for the given and the new information?

18.How can you prove that intonation transmits feelings and / or emotions?

19.What is the grammatical function of intonation?

20.Define intonology.

21.How is the distinctive function of intonation realized?

22.What are allotones and what are their types?

108

23.What does the number of terminal tones indicate?

24.What is the semantic centre of an utterance?

25.What content/notional words and function/structure/form words?

26.What are words highlighted in an utterance with?

27.Define sentence stress/utterance-level stress?

28.What is its main function ? What does deictic mean?

29.What are means of this accentuation ?

30.Discuss cases when function words are used in their strong and weak forms.

31.What do function words exhibit in their weak forms?

32.What is the sentence focus and where is it located in unmarked utterances?

33.How can a speaker place special emphasis on a particular element in an utterance?

34.What are anaphoric words? What is their function? Give examples.

35.What is de-accenting? What are its means and function?

36.How would you define the role of sentence stress/utterance-level stress?

37.Define rhythm.

38.Define rhythmic group.

39.What are proclitics and enclitics?

40.What is necessary for a learner to acquire a good English speech rhythm?

41.How is the incoming stream of speech decoded?

42.What is schemata?

43.What do listeners perform while decoding speech?

44.What is one of the most important units that contributes to successful speech processing in oral discourse?

45.What signals do listeners attend to trying to identify the end of one intonation unit and the beginning of another?

46.What are important functions of prosody in oral discourse? Explain each of the function and give examples.

Practical task

1.Make a glossary of the main notions and give their definitions.

2.Explain the following functions of intonation as singled out: a) by David

Crystal.

|

Function |

Explanation |

1. |

Emotional |

|

2. |

Grammatical |

|

3. Information structure |

|

|

4. |

Textual |

|

5. |

Psychological |

|

6. |

Indexical |

|

b) Peter Roach.

Function |

Explanation |

|

1. Attitudinal |

|

|

2. |

Accentual |

|

3. |

Grammatical function |

|

4. Discourse function |

|

|

109

3. Match the given utterances with the adequate nuclear tone and attitude.

a. FALL |

b. RISE |

c. FALL-RISE |

d. RISE-FALL |

|

finality, |

|

general questions, |

uncertainty, doubt |

surprise, being |

definiteness |

listing, "more to |

requesting |

impressed |

|

|

|

follow", encouraging |

|

|

____1. It's possible. |

|

|

||

____2. It won't hurt. |

|

|

||

____3. I phoned them right away (and they agreed to come). |

|

|||

____4. Red, brown, yellow or.... |

|

|

||

____5. She was first! |

|

|

||

____6. |

I'm absolutely certain. |

|

|

|

____7. This is the end of the news. |

|

|

||

___8. |

You must write it again (and this time get it right). |

|

||

___9. |

Will you lend it to me? |

|

|

|

___10. It's disgusting!

4. Mark the nuclear tone you think is appropriate in the following responses.

Verbal context |

Response-utterance |

Nuclear tone |

It looks nice for a swim. |

It's rather cold (doubtful) |

|

I've lost my ticket. |

You're silly then ( stating the obvious) |

|

You can't have an ice-cream. |

Oh, please (pleading) |

|

What times are the buses? |

Seven o'clock, seven thirty, ...(listing) |

|

She won the competition. |

She did ! (impressed) |

|

How much work have you got |

I've got to do the shopping (and more |

|

to do? |

things after that) |

|

Will you go? |

I might. ( uncertain) |

|

5. Define the sentence focus in every case.

Mary told John all the secrets. (Not just a few secrets)

Mary told John all the secrets. (She didn't tell Richard, or Harold or...) Mary told John all the secrets.(She didn't hint, imply them...)

Mary told John all the secrets. (It wasn't Angela, or Beatrice or...)

Mary told John all the secrets. (She told him not the news, or the story...).

6. Read the following dialogue and mark the accents.

A Have you taken your family to the zoo, yet, John? B No, but my kids have been asking me to.

I've heard this city has a pretty big one.

A Yes, it doesn't have a lot of animals, but it has quite a variety of animals. I think your kids would enjoy seeing the pandas.

B I'm sure they would. I'd like to see them, too.

A Also, the tigers are worth looking at. B Is it okay to feed them?

A No, they're not used to being fed.

B What bus do you take to get there?

A Number 28. But don't you have a car?

B We used to have one, but we had to sell it.

110