The Economic History of Byzantium From

.pdf660 BORTOLI AND KAZANSKI

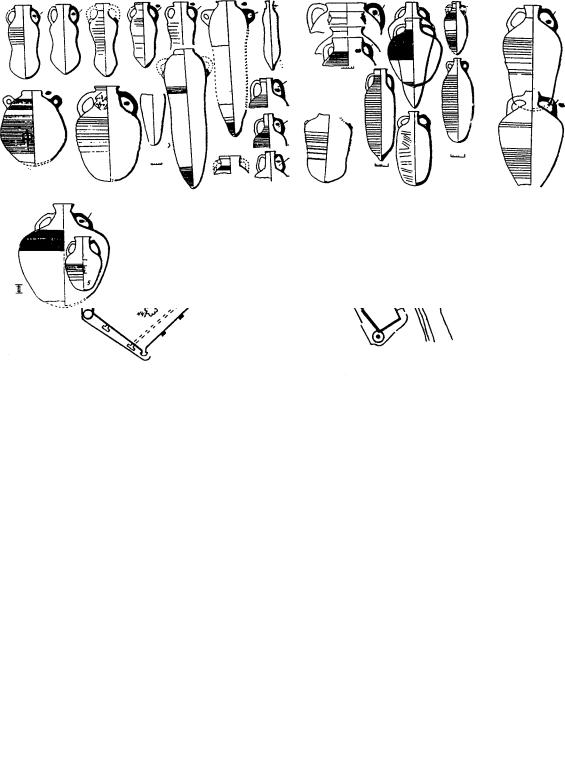

At the end of the sixth and the beginning of the seventh centuries,2 Kherson experienced a period of growth evident in a variety of ways, especially in the new buildings (notably the great quatrefoil church near the town’s west gate) and in the abundant evidence pointing to extensive foreign trade (amphoras, terra sigillata, and glass from the Mediterranean). For instance, the closed contexts from the end of the sixth and the first quarter of the seventh centuries (Cistern 92, the well in the first town quarter, or the house with the pithoi) have produced amphoras and terra sigillata vessels from the Mediterranean basin (including LRA [Late Roman Amphora]-1, LRA-2, LRA-3, LRA-5, Keay LXII, “Carrot” amphoras, Egyptian spateia amphoras, terra sigillata LRC, and African amphoras.3 These finds serve to confirm Kherson’s importance as a port (Fig. 2). During this period, Kherson also possessed a mint, and the local population was very productively engaged in, for instance, fishing and manufacturing work. That the catch was large is indicated by the considerable number of cisterns for salting fish (Fig. 3).4 Furthermore, archaeological finds have revealed the manufacture of metal artifacts, especially jewelry and accessories for clothes (belt buckles with decorative plaques, both the gadrooned and the cruciform types).5 These objects are distributed throughout the Crimea and were copied by the peninsula’s craftsmen.6 Although Kherson’s agricultural surroundings have not been sufficiently studied, the archaeological evidence from parcels of farmland around the town shows that a few agricultural units continued to be worked from the Roman period to the sixth and seventh centuries.7 Rural habitation sites, dated by Mediterranean amphoras to the sixth to seventh centuries, have been spotted close to the town, notably in Kilen-Balka, Zagaitanskaia Skala, and on the peninsula of Herakleia. These unfortified sites were agricultural, formed from units of farmland linked by roads. The dwellings were surrounded by buildings of an economic nature: grain silos, mills, and winepresses have been exca-

2 See the bibliography for Kherson and the Crimea during the earlier period in A. Bortoli-Kazanski and M. Kazanski, “Les sites arche´ologiques date´s du IVe au VIIe sie`cle au nord et au nord-est de la

´

mer Noire: Etat des recherches,” TM 10 (1987): 437–89; M. Kazanski and V. Soupault, “Les sites arche´ologiques de l’e´poque romaine tardive et du haut Moyen-Age en Crime´e (IIIe–VIIe s.): Etat des recherches (1990–1995),” in Les sites arche´ologiques en Crime´e et au Caucase durant l’Antiquite´ tardive et le haut Moyen Age (Leiden, 2000), 253–93.

3A. I. Romanchuk and A. V. Sazanov, Srednevekovyi Kherson: Istoriia, stratigrafiia, nakhodki, vol. 1, Krasnolakovaia keramika rannevizantiiskogo Khersona (Sverdlovsk, 1991); A. I. Romanchuk, A. V. Sazanov, and L. V. Sedikova, Amfory iz kompleksov vizantiiskogo Khersona (Ekaterinburg, 1995); A. Sazanov, “Les ensembles clos de Kherson de la fin du VIe s. au troisie`me quart du VIIe s.: Les proble`mes de la chronologie de la ce´ramique,” in Les sites arche´ologiques (as above, note 2), 123–49.

4Romanchuk, Khersones, VI–IX, 14; eadem, “Plan rybozasolochnykh cistern Khersonesa,” ADSV 14 (1977): 18–27.

5A. Ajbabin, “La fabrication des garnitures de ceintures et des fibules `a Kherson, au Bosphore Cimme´rien et dans la Gothie de Crime´e aux VIe–VIIIe sie`cles,” in Outils et ateliers d’orfevres des temps anciens (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 1993), 167; M. Kazanski, “Les plaques-boucles mediterrane´ennes du Ve–VIe sie`cles,” Arche´ologie me´die´vale 24 (1994): 162, 163.

6Ajbabin, “La fabrication.”

7For rural habitats in the Crimea, see, in the first instance, A. L. Jakobson, Rannesrednevekovye sel’skie poseleniia Iugo-Zapadnoi Tavriki, Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR 168, (Leningrad, 1970).

1. Map of medieval Kherson, 11th–14th centuries: A: the fortress; B: the port (after A. I. Romanchuk, Khersones, XII–XIV vv. [Krasnoiarsk, 1986], 11, fig. 1)

2. Amphoras discovered in the port quarter, Kherson, 7th century (after A. I. Romanchuk and O. R. Belova, Antichnaia drevnost’ i srednie veka 24 [1987]: 61, figs. 2, 3)

3. Topography of the medieval cisterns for salting fish, Kherson (after A. I. Romanchuk, in Antichnaia drevnost’ i srednie veka 14 [1977]: 24)

4. Molds for casting objects in bronze, 9th–10th centuries, Kherson (after A. L. Iakobson, Rannesrednevekovyi Khersones [Moscow–Leningrad, 1959], 327, fig. 179)

5. Kherson, a quarter in the northern part of the town, excavated in 1940 (after A. L. Iakobson, Srednevekovyi Khersones, XII–XIV vv. [Moscow– Leningrad, 1950], 154, fig. 89)

6. Agricultural implements, Kherson, 12th–14th centuries (after Iakobson,

Srednevekovyi Khersones, 95, fig. 44)

Kherson and Its Region |

661 |

vated.8 The presence of Mediterranean amphoras reveals that this rural environment was in contact with towns, primarily Kherson. On the other hand, finds made in sixthand seventh-century necropoleis in the countryside around Kherson (Chernaia Rechka, Inkerman, Sakharnaia Golovka) indicate the presence of a Hellenized barbarian population (mainly Alans and Goths).9

For the period from the mid-seventh to the eighth centuries, known as the Dark Ages, we possess an account by Pope Martin I. He was exiled to Kherson in 655, where he wrote an account of the high cost of living and food shortages that illustrates the very difficult economic situation prevailing there.10 This picture is slightly modified by the rare archaeological evidence. Imported Mediterranean amphoras and terra sigillata (LRA-1, LRA-2, LRA-4, LRA-5/6, and some African terra sigillata Hayes 95, 105, LRC 3F and G, etc.) have been found in Kherson dating from the second half of the seventh century (notably in the burned level near section XVIII, dated to 650–670 by coin finds of 641–668).11 Traces of bronze workshops have also been found, together with molds for the manufacture of ornaments for belt straps typical of the seventh century, molds for casting square buckles, dated to the second half of the seventh and eighth centuries, and rigid buckles with plaques, rejected as imperfect, dating from the second half of the seventh century.12 As in the preceding period, products from these workshops were widely distributed throughout the Crimea. It was precisely during the second half of the seventh and eighth centuries that the civilization of the southwestern Crimea shows the influence of Byzantium, in both the population’s clothing and its funerary practices.13 The town of Kherson also retained its Byzantine character and could not be described as barbarian or as barbarized. So the causes of the crisis recorded by Pope Martin I must be sought among the political events that were then rocking the empire and, most particularly, the Crimea: the Turco-Khazar conquests, which destroyed the town’s traditional links with the rest of the peninsula.

The Crimea experienced new growth between the eighth and tenth centuries, reflecting the improved political situation: the alliance with the Khazar kingdom and the settlement of a new sedentary Turco-Bulgarian population on the peninsula.14 Some historians also stress the role of Greek immigration from Byzantium.15 While this immigration has not yet been proven, the Byzantinization of the Crimea’s material culture is still obvious in this period. It was manifest in the population’s clothing, pottery, and

8 I. A. Baranov, “Pamiatniki rannesrednevekovogo Kryma,” in Arkheologiia Ukrainskoi SSR 3 (1986): 237.

9Ajbabin, “La fabrication.”

10O. R. Borodin, “Rimskii papa Martin I i ego pis’ma iz Kryma,” in Prichernomor’e v srednie veka (Moscow, 1991), 173–90.

11Sazanov, “Les ensembles clos”; A. I. Romanchuk and O. R. Belova, “K probleme gorodskoi kul’tury rannesrednevekovogo Khersonesa,” ADSV 54 (1987): 52–68.

12Ajbabin, “La fabrication,” 167.

13Baranov, “Pamiatniki,” 240, 241; I. A. Baranov, Tavrika v epokhu rannego srednevekov’ia (Kiev, 1990), 106–9, 129–39.

14For the Khazar presence and the Turco-Bulgarian population in the Crimea, see Baranov, Tavrika.

15Baranov, “Pamiatniki,” 241.

662 BORTOLI AND KAZANSKI

glass.16 In the same way, the dominance of typically Byzantine funerary rites may be observed (inhumation in tombs built of stone slabs), as well as the construction of new basilicas in rural sites (for instance, in Partenit and Tepsen).17 Although there is some argument18 about the state of Kherson’s economy, it did retain its political and military role. As indicated above, the governor of Kherson’s climata (the area under Byzantine rule in the southwestern Crimea) had his seat in the town. With regard to the townsfolk’s employment, the discovery of cisterns for salting fish19 and depots of pithoi shows how important the fishing industry was. Traces of several workshops have been found, notably bronze workshops (Fig. 4)20 manufacturing buckles with plaques for Corinthtype belts (8th–9th centuries),21 and pottery workshops producing amphoras, tiles, and pitchers.22

During the second half of the ninth century, Kherson’s mint struck an increased quantity of coins, which suggests that trade was flourishing. We know that Kherson retained close economic relations with the rest of the Crimea because the town’s manufacturing products are found elsewhere in the peninsula. Many amphoras from the eighth to tenth centuries have been discovered north of the Black Sea and they too probably came from Kherson, where, as we know, amphoras were manufactured at that time. Among the finds from Kherson dated to the ninth and tenth centuries, the non-Byzan- tine pottery requires a mention: Turco-Bulgarian or Alan pottery from the Khazar kingdom and pottery from Trans-Caucasus.23 Indeed, there is plenty of evidence for commercial relations with the Khazar kingdom.24 As for economic contacts with Byzantium, these can be substantiated by the discovery of amphoras from Constantinople and of glazed wares. The similarity between the pottery (notably amphoras), metal goods, and glass from Kherson and those of the Mediterranean world presupposes very close economic relations. As yet, little is known about the town’s agricultural surroundings. Evidence for continuity during the eighth to tenth centuries is known only in the case of Zagaitanskaia Skala, Kamyshovaia Bukhta, and Khomutova Balka. Zagaitanskaia Skala retained the same character as in the preceding period. At

16See, notably, A. I. Aibabin “Mogil’niki VIII–nachala X vv. v Krymu,” Materialy po arkheologii, istorii

ietnografii Tavrii 3 (1993): 121–32.

17Baranov, “Pamiatniki,” 243.

18A. L. Jakobson thinks that the town underwent a profound decline during the Dark Ages, from which it emerged only at the end of the 9th century and, especially, during the 10th century. Jakobson, Rannesrednevekovyi Khersones, 35, 36; idem, Srednevekovyi Krym (Leningrad, 1964), 27; idem, Krym

vsrednie veka (Moscow, 1973), 30, 31. A. I. Romanchuk stresses that economic activity persisted at Kherson during the 7th to 8th centuries. Romanchuk, Khersones; A. I. Romanchuk and L. V. Sedikova, “‘Temnye veka’ i Kherson: Problema representativnosti istochnikov,” in Vizantiiskaia Tavrika (Kiev, 1991): 30–46.

19Romanchuk, Khersones, VI–IX, 16.

20Ibid., 31; Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 129; for the molds and crucibles found at Kherson, see Jakobson, Rannesrednevekovyi Khersones, 322–30.

21Ajbabin, “La fabrication,” 168.

22Jakobson, Rannesrednevekovyi Khersones, 306, 307; Jakobson, Keramika, 31, 33, 39, 51–53, 71, 93.

23Jakobson, Keramika, 80–82.

24Bogdanova, “Herson,” 62–65.

Kherson and Its Region |

663 |

Kamyshovaia Bukhta, we know of several buildings arranged as a unit around a large courtyard. At Khomutova Balka, traces of a circular building, probably a tower, have been uncovered. This period came to an end in the tenth century, when Kherson was largely destroyed and burned, traces of this have been found in various town quarters. Some historians have attributed this disaster to the Russian prince Vladimir’s expedition against Kherson in 988.25

During the eleventh to fourteenth centuries, Kherson was the last Byzantine possession north of the Black Sea from which the empire was still able to control the southwestern Crimea. While the town retained its importance in the eleventh to twelfth centuries, the situation altered during the thirteenth century.26 The installation of Tatars during the first half of the thirteenth century and the Golden Horde’s acquisition of the peninsula directed the Crimea’s economic links eastward. Furthermore, military action by the Tatars, notably the destruction of the town at the end of the thirteenth century by Khan Nogai, caused Kherson’s economic situation to deteriorate further. In the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, Kherson was exposed to keen competition from the Italian traders of Kaffa. All of this contributed to the town’s political and economic decline, leading to its demise at the very end of the fourteenth century, when the Tatars destroyed the town. Archaeologists have nonetheless found evidence, even in this final period, of a well-developed local manufacturing industry. Several pottery workshops have been discovered, including a thirteenth-century one that produced tiles (Fig. 5), a bone workshop and a forge dating from the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, two metal workshops, one dating from the ninth to eleventh centuries and the other from the end of the twelfth and the thirteenth centuries, and many traces of glass manufacture.27 The craftsmen worked partly to order and partly for the market, using mainly local raw materials. The workshops were mostly small and set in the inhabited quarters alongside the craftsmen’s houses (Fig. 5).28

By this period, it is noticeable that the town had to some extent become more agricultural, as manifested by a more intensive use of agricultural land in the suburbs. The houses have been found to contain grains of wheat, oats, and millet as well as the bones of bovidae and cervidae, horses, pigs, and fowl. Agricultural implements are also well represented among the archaeological finds in Kherson’s stratigraphical layers dating to that period (Fig. 6).29 Fishing also retained its importance as a secondary form of employment: we know of two cisterns for salting fish that date from the ninth to twelfth centuries. Written sources provide evidence of salt-panning by the inhabitants during this period. Kherson was still a maritime port in spite of competition from the port of Balaklava, which belonged alternately to the prince of Theodoro (modern

25Jakobson, Rannesrednevekovyi Khersones, 65; idem, Srednevekovyi Khersones, 14; for a critique of this point of view, see A. I. Romanchuk, “Sloi razrusheniia X v. v Khersonese,” VizVrem 50 (1989): 182–88.

26Regarding recent discoveries from this period in Kherson, see Romanchuk, Khersones, XII–XIV vv.

27Jakobson, Keramika, 155–57; Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 24, 30, 34.

28Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 43–46.

29Jakobson, Srednevekovyi Khersones, 95, 96; Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 46–50.

664 BORTOLI AND KAZANSKI

Mangoup) and to Italians. The town’s outside contacts were directed mainly toward Asia Minor, and these economic links serve in part to explain its political orientation toward the empire of Trebizond. On the other hand, archaeologists have uncovered evidence for a substantial Russian trading presence in the town.30 Amphoras from Asia Minor, glazed Byzantine wares, glass, ivories, and decorated enamel artifacts from Constantinople point to the persistence of foreign trade, notably with the Mediterranean.31 Some copper and lead ingots originated in Asia Minor.32 The town’s economic contacts with the rest of the Crimea remained important, since part of its manufacturing produce was distributed among the villages and small towns of the southwestern Crimea (Mangoup, Eski-Kerman). Unfortunately, Kherson’s agricultural surroundings in the eleventh to fourteenth centuries have not been sufficiently studied for their features to be properly known.

The town’s social and economic topography in this period can be observed fairly easily. Whole workshops have been excavated in the north and northwest parts near the coast.33 Analysis of the houses in the northern sector has shown that the population included merchants, carpenters, masons, bronzeworkers, fisherfolk, priests, bakers, and innkeepers.34 We know that this sector also contained foreign merchants because several houses have been identified by archaeologists as belonging to a Russian community.35 In the part by the port, the archaeological evidence points to the presence of Italian, Russian, Armenian, Arab, Tatar, and Alan nationals who were certainly involved in trade. Craftsmen and merchants also lived in the northeastern quarters, where the large public buildings were still sited during this period. There is evidence showing that the inhabitants of this sector (especially in sections III, VI, and VII) were prosperous.

30Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 77–81.

31Jakobson, Keramika, 111; Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 55–59, 71–77.

32Bogdanova, “Kherson,” 24.

33Jakobson, Srednevekovyi Khersones, 94–100; Romanchuk, Khersones, XII–XIV vv., 77–92.

34Romanchuk, Khersones, XII–XIV vv., 81–92, pl. 1.

35Ibid., 44.

Kherson and Its Region |

665 |

Bibliography

Bogdanova, N. M. “Kherson v X–XV vv.: Problemy istorii vizantiiskogo goroda.” In

Prichernomor’e v srednie veka. Moscow, 1991.

Bortoli-Kazanski, A., and M. Kazanski. “Les sites arche´ologiques date´s du IVe au VIIe sie`cle au nord et au nord-est de la mer Noire: Etat des recherches.” TM 10 (1987): 437–89.

Jakobson, A. L. Srednevekovyi Khersones, XII–XIV vv. Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR 17. Moscow–Leningrad, 1950.

———.Rannesrednevekovyi Khersones. Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR 63. Moscow–Leningrad, 1959.

———.Keramika i keramicheskoe proizvodstvo srednevekovoi Tavriki. Leningrad, 1979.

M. Kazanski, and V. Soupault, “Les sites arche´ologiques de l’e´poque romaine tardive et du haut Moyen-Age en Crime´e (IIIe–VIIe s.): Etat des recherches (1990–1995).” In Les sites arche´ologiques en Crime´e et au Caucase durant l’Antiquite´ tardive et le haut Moyen Age (Leiden, 2000).

Romanchuk, A. I. Khersones VI–pervoi poloviny IX v. Sverdlovsk, 1976.

———. Khersones, XII–XIV vv.: Istoricheskaia topografiia. Krasnoiarsk, 1986. Romanchuk, A. I., and A. V. Sazanov. Srednevekovyi Kherson: Istoriia, stratigrafiia, na-

khodki. Vol. 1, Krasnolakovaia keramika rannevizantiiskogo Khersona. Sverdlovsk, 1991. Romanchuk, A. I., A. V. Sazanov, and L. V. Sedikova. Amfory iz kompleksov vizantiiskogo

Khersona. Ekaterinburg, 1995.

Preslav

Ivan Jordanov

In the year 6477 (969), Svjatoslav is reported as saying, “I . . . should prefer to live in Pereiaslavets on the Danube, since that is the center of my realm, where all riches are concentrated: gold, silks, wine, and various fruits from Greece, silver and horses from Hungary and Bohemia, and from Rus’ furs, wax, honey, and slaves.” (Russian Primary Chronicle, XI C. “Povest’ vremennykh let”). Medieval Preslav was situated south of the modern town of the same name. The name Preslav is mentioned in the written sources—inscriptions, seals, and Byzantine and Bulgarian chronicles—in various forms:

, Presqla´ ba, Iwannouj´poli", Presqlabi´tza, Mega´ lh Presqla´ ba,

, Presqla´ ba, Iwannouj´poli", Presqlabi´tza, Mega´ lh Presqla´ ba,

, Eski Stamboul.

, Eski Stamboul.

Judgments about the place and role of Preslav in medieval Bulgaria, Byzantium, and the world of the time can be reached on the basis of the information provided by contemporaneous sources and of the data from archaeological excavations. Regular archaeological excavations have been conducted in Preslav for nearly a hundred years, and the picture of life in the city they suggest is summarized here.

The medieval settlement of Preslav was founded during the eighth to ninth century. Before being proclaimed the capital of Bulgaria, it had been a strategic fortress. It was the residence of one of the chief assistants of the ruler, the Icergu¨ Boila (hjtzi´rgwn bwu¨le)—a military commander and diplomat—and it had a strong garrison and stores for heavy armaments (chain-mail and helmets) to equip a large part of the Bulgarian army.1 Preslav was proclaimed the capital of Bulgaria in 893. It was captured in 969 by Sviatoslav of Kiev and in 971 by John I Tzimiskes. The Bulgarians reoccupied it in ca. 986, and the Byzantines about the year 1000. Thus it was under Byzantine rule from 971 to 986 and from 1000 to 1185. Under the second Bulgarian empire (1185– 1393), Preslav remained an important city until its capture by the Ottoman Turks in 1388. This discussion of the economy of Preslav covers both the period when Preslav was a capital city and the period of Byzantine rule. The chronology of the archaeological finds is not always easy to establish.

1 I. Venedikov, Voennoto i administravnoto ustroistvo v Srednovekovna Bu˘lgaria prez IX i X vek (Sofia, 1979), 23–24, 39–40.