The Economic History of Byzantium From

.pdf

9. Chronological distribution of amphora finds in the Italian excavations at Carthage

(L. Anselmino, C. Panella, R. S. Valenzani, S. Tortorella, “Cartagine,” in A. Giardina, ed.,

Società romana e impero tardoantico, vol. 3, Le merci, gli insediamenti, [Rome, 1986], 178, fig. 11)

210 MORRISSON AND SODINI

prefect of Illyricum vainly sought help from the island at the beginning of the seventh century.233

Oil and wine came for the most part from Syria or Palestine, a fact evidenced by the pottery of Sarac¸hane, where LRA (Late Roman Amphora) 1 amphoras produced on the Cilician coast, probably in northern Syria, and also in Cyprus, constitute threequarters of the amphora fragments. Grain, oil, and wine—the only products mentioned in the decree of Abydos, together with dried legumes and salt pork234—consti- tuted a large portion of the south-to-north exchanges of the eastern Mediterranean and represented the backbone of the Byzantine empire’s domestic commerce during the sixth century. The role of the annona and the public distributions remains difficult to state precisely; it was determinative according to some (Jean Durliat), less so according to others (V. Sirks and J.-M. Carrie´), a position that appears more plausible, all the more since the essential foodstuffs were supplemented by textiles, perfumes, unguents, papyrus, and metal, or wood—raw material for the artisanal industry of the capital.235

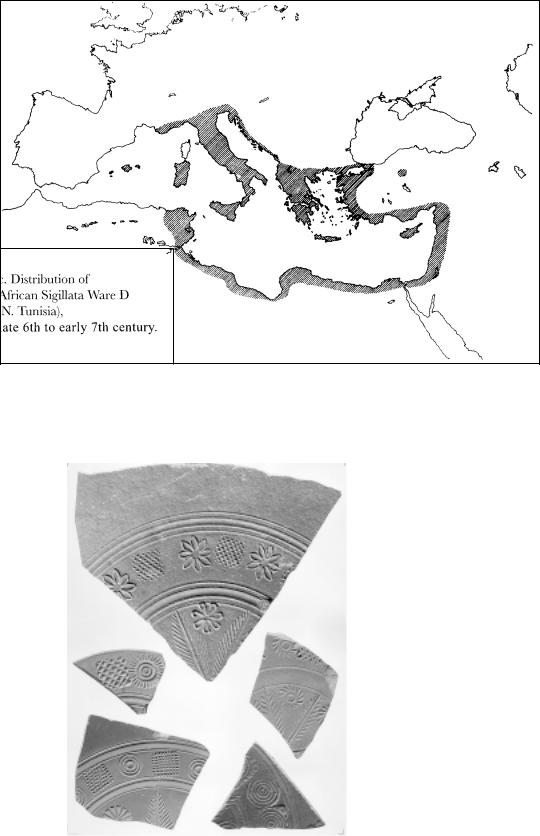

The second commercial route was not entirely secondary: it united Constantinople with “Libya and Italy”—the places of origin of the ships mentioned by Prokopios in connection with the customs stations erected on the Straits (Anecdota 25.7–10). The eastern amphoras discovered in excavations at Carthage (Fig. 9) confirm the persistence of these ties. The African route is marked out by finds of high-quality tableware (African Red Slip) made in Africa Proconsularis and lamps from Byzacena. This cargo was shipped together with heavy products and was distributed throughout the East, not only in Constantinople, but also in Asia Minor, in southern Greece, and, possibly to a lesser degree, in the Black Sea region (Fig. 10). While it competed against Phokaian Sigillata ware, which clearly dominated the market in the northern Aegean (80% at Demetrias), in Constantinople, and in Asia Minor, African Red Slip ware assumed an increased importance over the years 500–550 in Argos (in which it constituted 40% of high-quality ware), as well as in Athens, Kenchreai, and Sparta. The distribution of African Red Slip ware also emphasizes the existence of lively east-west relations that, by way of Crete, directly united Africa with the urban centers of Syria-Palestine, Antioch and Caesarea. Phokaian Sigillata ware, by contrast, had a “capillary” distribution, reaching interior territories in Asia Minor, Greece, and the East, a fact that suggests “a small trade in peddling.”236

Archaeological and numismatic material also maps out the western routes of trade beyond the empire’s limits.237 The Mediterranean was, despite the occasional raids by

233Theophanes, Chronographia, ed. C. de Boor, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1883–85; repr. Hildesheim, 1963), 1:296; Lemerle, Miracles de Saint De´me´trius, 1: miracle 9, §§ 74–78, pp. 106–7.

234Text, translation, and commentary by G. Dagron, in G. Dagron and D. Feissel, “Inscriptions ine´dites du Muse´e d’Antioche,” TM 9 (1985): 421–61 (app. at 451–55). Analyses of the contents of the amphoras reveal a similar diversity: cereals, wine, oil, honey, dates, and pulses (Hayes, Sarac¸hane, 434).

235See the survey of the question and Carrie´’s own position in J.-M. Carrie´ and A. Roussel, L’empire romain en mutation des Se´ve`res `a Constantin, 192–337 (Paris, 1999), 687–91.

236C. Abadie-Reynal, “Ce´ramique et commerce dans le bassin ´ege´en du IVe au VIIe sie`cle,” in Hommes et Richesses (as above, note 15), 1:143–62.

237J.-P. Callu, “I commerci oltre i confini dell’impero,” in Schiavone, Storia di Roma (as above, note 68), 487–524.

The Sixth-Century Economy |

211 |

Vandal pirates, Byzantium’s inner sea, and Byzantine trade extended to the west as far as England, and, to the east, reached India by way of the Red Sea, and Central Asia (albeit with greater difficulty) by land. The French shipwrecks at La Palud (Port-Cros) and Saint-Gervais (Fos),238 like the pottery finds at Marseilles, testify to relations between Gaul and the Byzantine East and Africa. In the excavations at Marseilles, the abundant presence of eastern amphoras declines to 25% at the end of the sixth century and disappears altogether at the end of the seventh, whereas African amphoras, abundant in the fourth century, in the minority in the fifth (20–30%), predominate again (46%) at the end of the sixth century.239 The distribution of LRA 1 and LRA 4, used in particular for the transport of wine from Laodicaea and Gaza, often mentioned by Gregory of Tours, reaches as far as the southwest coast of England and indirectly confirms the famous anecdote of the boat from Alexandria reaching Britain in the Life of St. John the Almsgiver.240

To the east, the Sasanians dominated the gulf 241 and thus a portion of trade in the Indian Ocean, as well as the principal land itineraries of the Silk Route. We know that exchanges were prohibited outside the customs posts of Nisibis, Callinicum, and Artaxata; this affected trade in silk and other luxury products, such as pearls brought by the son of a wealthy Persian merchant from Rev Ardashir to Nisibis, where he converted and became a monk.242 The maritime route was not entirely controlled, however, and Byzantine, Axumite, or Himyarite merchants reached as far as Taprobane (Ceylon), as Cosmas Indicopleustes recalls in an often cited text, or southern India as attested by the finds of solidi spanning the reigns of Theodosios II to Herakleios. Together with the shipping lanes of the Red Sea, caravan routes uniting southern Arabia with Syria flourished in the sixth century; this trade contributed to the prosperity of all the way stations of the Mediterranean, but in particular Clysma “ubi etiam et de India naves veniunt,”243 and Adulis, a fact that explains in part at least the conflicts and battles for influence that unfolded during this period between the Axumites, who were supported by Byzantium, and the pro-Sasanian Himyarites.244 The evidence of

238See F. van Doorninck, Jr., “Byzantine Shipwrecks,” EHB; L. Long and G. Volpe, “Le chargement de l’e´pave 1 de la Palud (VIe s.) `a Port-Cros (Var): Note Pre´liminaire”, in Fouilles `a Marseille, Les mobiliers (Ier–VIIe sie`cles ap. J.-C.) (Aix-en Provence, 1998), 317–342; M.-P. Je´ze´gou, “Le mobilier de l’e´spave Saint-Gervais 2 (VIIIe s.) `a Fos-sur-Mer (B.-du Rh.), ibid., 343–51.

239Loseby, “Marseille,” recalculating the data published by M. Bonifay, “Observations sur les amphores tardives de Marseille d’apre`s les fouilles de la Bourse, 1980–1984,” Revue arche´ologique de Narbonnaise 19 (1986): 269–305.

240C. Thomas, “Tintagel Castle,” Antiquity 62 (1988): 421–34; S. Lebecq, “Gre´goire de Tours et la vie d’e´changes dans la Gaule du VI sie`cle” in Gre´goire de Tours et l’espace gaulois, ed. N. Gauthier and H. Galinie´ (Tours, 1997), 169–76.

241The warehouse of Kane (Bir Ali) on the Strait of Hormuz shipped continuous series of pottery

´

dating from the 1st century C.E. to the 7th century: P. Ballet, “L’Egypte et le commerce de longue distance: Les donne´es ce´ramiques,” Topoi 6 (1996): 826–28. Amphoras of type LRA 1 and 4 have been identified, as well as cylindrical African amphoras associated with LRA Sigillata. Amphoras from Ayla (present-day Aqaba) support the argument that it was active as a port until the mid-7th century.

242J.-B. Chabot, “Le Livre de la chastete´ compose´ par Je´susdenah ´eveˆque,” Me´lRome 16 (1896): 27, 248.

243Antoninus Piacentinus (ca. 570), Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 175, A 41, 6, 151.

244For the details, see Callu, “I commerci,” 511–520.

10a

10b

10c

10a–c. Distribution of African Sigillata ware (after S. Tortorella, “La ceramica fine da mense africana dal IV al VII secolo da Cristo,” in Società romana e impero tardoantico, vol. 3, Le merci, gli insediamenti, ed. A. Giardina [Rome, 1986], 217–19)

Sigillata D from the site of El-Mahrine (after M. Mackensen, Die spätantiken Sigillataund Lampentopfereien von el Mahrine (Nordtunesien): Studien zur nordafrikanischen Feinkeramik des 4. bis 7 Jahrhunderts [Munich, 1993], 210, fig. 56)

212 MORRISSON AND SODINI

known texts (Prokopios, Cosmas) is confirmed by archaeological and numismatic data: the presence of amphoras from Aqaba throughout the Red Sea region and at Axum, and finds of Axumite coins in Jerusalem, testify to relations that were not exclusively religious.245

The picture of commerce as a whole that we have briefly sketched was transformed in the second half of the sixth century. Trading volume dropped; the trade routes themselves are more difficult to unravel, a reflection, perhaps, of political upheavals. The Byzantine empire now maintained scarcely any contacts with western Europe beyond southern Italy (Otranto), Sicily, Ravenna, Venice, and certain points along the Adriatic, as well as Naples, Rome, and the ports of the Ligurian coast.246 Globular amphoras closely related to the Carthaginian LRA 2 amphoras, possibly produced simultaneously in both East and West, were distributed throughout the Mediterranean basin and the Black Sea,247 but they represented little more than the persistence of a commerce that at the start of the sixth century had been substantial and differentiated.

Money, the Instrument of Exchange

Byzantine money provided a flexible and hierarchical instrument for the empire’s substantial level of exchange.248 We concentrate here on its specifics with regard to the sixth century. Three major events marked the monetary history of this period: Anastasios’ reform of the bronze coinage; the adoption, following the Justinianic reconquest, of the Vandal and Ostrogoth monetary systems in Africa and Italy; and, finally, the inflation of small-denomination coinage during the second half of the century. The reform undertaken by Anastasios in 498 was sufficiently noticed by intellectuals to find mention in a good number of texts, which are usually chary of such data. The reform put an end to a long period of inflation in smaller denominations, whose value relative to the solidus dropped from 1⁄5,400 in 396249 to 1⁄7,200 in 445 or, in 498, to 1⁄16,800, at which point it no longer exceeded 0.6–0.5 g, or even 0.2 g (Table 1).250 The decline in the gold value of bronze money became particularly noticeable in the reign of Zeno by virtue of

245S. C. Munro-Hay, “The Foreign Trade of Adulis,” AntJ 69 (1989): 43–52.

246P. Arthur, “Anfore dall’alto Adriatico e il problema del Samos Cistern Type,” Aquileia Nostra 61 (1990): 282–95.

247Hayes, Sarac¸hane, 61–79 (types 9, 10, 28, 29, 30, corresponding to several productions from the 6th to the early 8th century; G. Murialdo, “Anfore tardoantiche nel Finale (VI–VII secolo),” Rivista di studi liguri 59/60 (1993–94): 213–46; L. Sagui, M. Ricci, D. Romei, “Nuovi dati ceramologici per la storia economica di Roma tra VII e VIII secolo,” in La ce´ramique me´die´vale en Me´diterrane´e (Aix-en- Provence, 1997), 35–48.

248Regarding the general characteristics, which remained prevalent at the beginning of the 7th century, see C. Morrisson, “Byzantine Money: Its Production and Circulation,” EHB.

249CTh 9.21.8, in which one solidus is equivalent to 25 pounds of bronze, while the nummus (AE4) weighs 1⁄216 pound, or approximately 1.5 g.

250See, among others, the studies published in L’inflazione nel IV secolo dopo C., Atti dell’incontro di studio, Roma 1988 (Rome, 1993), including J.-M. Carrie´, “Observations sur la fiscalite´ du IVe sie`cle pour servir `a l’histoire mone´taire,” 113–54, and Carrie´’s synthesis, “Les ´echanges commerciaux et l’e´tat antique tardif,” in Economie antique: Les ´echanges dans l’Antiquite´. Le roˆle de l’e´tat (Saint-Bertrand- de-Comminges, 1994), 174–211.

Solidus

Follis

Dekanoummion

Gold solidus of Anastasios, DOC 1:3i.1

Gold semissis of Justinian I, DOC 1:17.1

Gold tremissis of Justinian I, DOC 1:19.10

Silver siliqua of Justin II, DOC 1:18.3

Copper follis of Anastasios, DOC 1:23a.2

Semissis |

Tremissis |

Siliqua

Half follis

Nummus

Pentanoummion

Copper half follis of Anastasios, DOC 1:24c

Copper dekanoummion of Justinian I, DOC :34.5

Copper pentanoummion of Anastasios, DOC 1:49b

Copper nummus of Justinian I, DOC 1:308

214 MORRISSON AND SODINI

the financial troubles that followed the defeat of the expedition of 468 against the Vandals, which swallowed up, to no avail, sums corresponding to a year’s worth of public revenues.251

The sources indicate the characteristics of the reform and its consequences. The replacement of units of currency by the follis252 and its fractional denominations is described by Malalas: “[John the Paphlagonian] transformed all the small change that was in circulation (to` procwro`n ke´rma to` lepto`n) into follera, which he made current [legal tender] throughout the empire as of this date”;253 and by an anonymous Syriac chronicle, which specifies that “the emperor issued a coinage of 40, 20, 10, and 5 nummi.”254 Marcellinus Comes (ca. 498) offers the following commentary on the measure: “Nummis quos Romani terunciani [terentianos] vocant, Graeci follares, Anastasius princeps suo nomine figuratis placibilem plebi commutationem distraxit” (“in minting pieces marked with their value that the Romans called teronces and the Greeks follares, Emperor Anastasios implemented an exchange that was pleasing to the people”).255 The term “exchange” (commutatio) highlights the importance of the relations between the two components of the monetary system: gold and bronze.256 If the exchange was “pleasing to the people,” it was on the one hand because imprinting the value on the coins—a novelty that until this point had been used solely by the Vandals or the Ostrogoths—seemed a guarantee against arbitrary revaluations, and, on the other, because the relation to the solidus that was thus instituted undoubtedly favored the lower classes, whose cash property and earnings were most often limited to bronze coinage.

Calculating the equivalence of the follis and the solidus raises a number of technical problems too complex to treat here. The reconstruction that Morrisson has proposed demonstrates an evolution that was in fact favorable to holders of bronze currency under Justinian as of the 530s and especially in the 540s, following the plague. In the first instance, the reconquest of Africa, to some degree, undoubtedly brought new resources of precious metal to the treasury and thereby facilitated the lowering of the price of gold expressed in bronze; in the second, the increase in the cost of services, which was linked to the scarcity of manpower, explains the attempt to satisfy labor interests by lowering the price of the solidus, thus offsetting the prohibition on pay raises that had been decreed in 544 in Justinian’s Novel 122.257

It is likely, however, that this situation did not endure beyond the reign of Justinian. Certainly the weight of the follis remained stable at 18 g from 512 to 538 and from 542

251M. Hendy, Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy c. 300–1450 (Cambridge, 1985), 221.

252For details on the weight and gold value of the 6th-century Constantinopolitan follis, see C. Morrisson, “Monnaie et prix `a Byzance du Ve au VIIe sie`cle,” in eadem, Monnaie et finances `a Byzance: Analyses, techniques (Aldershot, 1994), art. 3, p. 248 ( Hommes et Richesses [as above, note 15], vol. 1).

253Ioannis Malalas, Chronographia, ed. L. Dindorf (Bonn, 1831), 400.

254Chronica minora, ed. E. W. Brooks, trans. J.-B. Chabot (Paris, 1924), 4:115.

255MGH AA 11.2 (ad annum 498). Commentary and references in Morrisson, “Monnaie et prix,” 243–44.

256See Morrisson, “Money,” 900–901 and passim. Silver coinage was practically never struck in 6th-century Constantinople except for ceremonial purposes.

257Commentary and references in Morrisson, “Monnaie et prix,” 246–48.

The Sixth-Century Economy |

215 |

to 565, following the episode of the large folles dated by regnal years XII–XV, whose face value was near their nominal value; it declined progressively until it reached 11–12 g under Maurice and the first years of Herakleios’ reign. The data provided in the papyri regarding the value of the follis in keratia, however, refine this view by showing a decline to 1⁄20 keratia under Phokas and to 1⁄36 under Herakleios.258

It is more than likely that this decline in the gold value of bronze money was the result of the striking of an increasing number of these coins by a government that lacked bullion and was forced as a consequence to reduce the weight of coins. This inflation entailed a rise in prices as expressed in small denominations, but we cannot track this as precisely as Roger Bagnall has done for the fourth century, in the course of which “prices rise almost immediately after each debasement such that the value of gold . . . in copper currency units is in line with the relationship between the face value of the coin and its metal content.”259 We may conclude that the minimum daily living allowance of the poor, of prisoners, and of ascetics—approximately 3 nummi at the start of the fifth century—had risen to 10 nummi during the sixth, and to 1 follis around 570, which was also its level at the beginning of the seventh century. The decline in the weight and purchasing power of the follis is equally illustrated by the progressive disappearance of smaller denominations in excavation finds: the pentanoummion, like the dekanoummion, becomes increasingly rare as of the 580s.

This picture applies equally to the situation in the capital and in the eastern provinces of the empire. In the West, by contrast, in the territories that were reconquered from the Vandal and Ostrogoth kingdoms, the Byzantine monetary system adapted itself to succeed the existing “barbarian” systems.

The role of silver in the Vandal and Ostrogoth monetary systems was not, as we can see, called into question after the reconquest, and the mints of Carthage and Italy (at Rome and Ravenna) continued to strike silver in various denominations. At Carthage, these denominations compensated in part for the absence of fractional denominations of the solidus; despite their high face value (a half siliqua of 50 denarii was worth approximately 6 folles), they must have played an important role in day-to-day exchange, since they have been found in considerable number in site excavations.260 Another distinctive quality of Byzantine currency in Africa and in Italy relative to eastern issues is the greater importance under Justinian of small copper coins and particularly of nummi of less than one gram. This weighting can be measured at the sites by calculating the average value of bronze finds in nummi. Under Justin II, it was on the order of 10 nummi at Carthage, as opposed to 21 nummi at Athens. With the inflation of the

258 |

J.-M. Carrie,´ |

“Monnaie d’or et monnaie de bronze dans l’Egypte protobyzantine,” in Devaluations´ |

|

´ |

(as above, note 129), 2:253–70. These data may be supplemented and confirmed in part by those contained in the same documents concerning the number of talents to the solidus, as well as those studied by A. Papaconstantinou, “Conversions mone´taires byzantines: P. Vindob. G. 1265,” Tyche 9 (1994): 95–96 (for example 23,400 ca. 538, 48,000 in 569, 51,200 in 618, when the follis was only worth 1⁄36 of a keration and weighed half of what it weighed in 512–538).

259 R. Bagnall, Currency and Inflation in Fourth-Century Egypt (Chico, Calif., 1985), 53.

260 C. Morrisson, “Le roˆle du monnayage d’argent dans la circulation africaine `a l’e´poque vandale et byzantine,” Bulletin de la Socie´te´ franc¸aise de Numismatique 44 (1989): 518–22.