- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

17 The Multidimensional Benefits of Terraced Landscape … |

279 |

17.2Evaluation Tools

17.2.1Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

The abandonment of cultural agrarian landscapes generates negative impacts (costs) on multiple dimensions: sociocultural, environmental and economic, undermining their Complex Social Value. Table 17.1 shows these impacts as they have been reported in the literature, which can be applied to terraced landscapes.

These multidimensional costs are avoided if we recover the circular model. They can become the benefits of reusing terraced landscapes, contributing to create new markets and jobs with high social and environmental impacts.

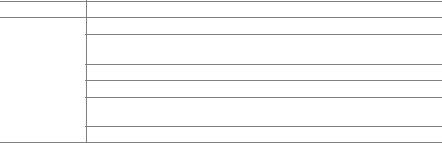

Table 17.1 Multidimensional impacts (costs) of land abandonment in terraced landscapes

|

Negative impacts (costs) of land abandonment |

Sociocultural |

Loss of cultural landscape (decrease in well-being) |

|

Loss of cultural identity and cultural diversity |

|

Loss of traditional knowledge |

|

Increased poverty and marginality of rural areas (loss of jobs in agriculture |

|

and agri-food sector) |

|

Ageing of rural/mountain population |

|

Increased social vulnerability of local populations |

|

In some extreme cases, loss of human lives due to landslide or flooding |

|

events |

|

Decrease of food sovereignty and food security in rural and related urban |

|

areas |

|

Negative impacts on human health/well-being due to loss of complex |

|

environmental factors and to loss of landscape beauty |

|

Impoverishment of agrarian biodiversity and irreversible loss of |

|

autochthonous seeds/agrarian qualities |

Environmental |

Increase of environmental risk (landslide, flooding, fire) |

|

Increased soil erosion |

|

Decrease of organic soil fertility |

|

Reduction of fresh water in aquifers related to less retention through |

|

canalizations, storage systems and water retention from terraces |

|

Increased climate-changing gas emissions related to unsustainable farming |

|

Increased climate-changing gas emissions related to food importation |

|

Loss of biological diversity related to higher environmental fragmentation |

|

Loss of habitat for autochthonous species |

|

Higher vulnerability to invasive alien species |

|

Increased pollution, waste and energy demand in urban areas due to |

|

increased migration flows |

|

(continued) |

280 |

L. Fusco Girard et al. |

Table 17.1 (continued)

Negative impacts (costs) of land abandonment

Economic Loss of attractiveness for tourism and recreation (long term)

Higher costs of recovery of productive lands (also for future generations) in medium–long term

Costs of recovery from environmental extreme events (short–medium term)

Decreased profit from food production (short term)

Negative spillover effects of increased poverty on local economy (short– medium term)

Loss of agricultural revenues

Here, we will focus our attention in particular on evaluation approaches and tools that can specify these multidimensional costs. Then, we analyse some economic instruments that can be used to implement a circular regeneration model in terraced landscapes, based on successful models implemented in cultural agrarian landscapes.

17.2.2The Ecosystem Services Assessment

for Operationalizing the Social Complex Value

Methods and tools applied in ecological economics (Common and Stagl 2005; Costanza et al. 2014) can be employed to assess the societal cost of land abandonment and conversion (Gaitán-Cremaschi et al. 2017).

The ecosystem services’ theory has provided meaningful definitions of ecosystem (and landscape) functions and services, and evaluation tools for their assessment, which are employed to understand the complex systems of relationships between land uses and their biophysical structures, functions and processes, and how they can be related to changes in human welfare (de Groot et al. 2010; Haines-Young and Potschin 2010). The concept of ecosystem functions and services has been introduced by Costanza et al. (1997) and further explored by the ‘Millennium Ecosystem Assessment’ (MEA 2003; MA 2005). Ecosystem Services (ES) have been defined by MEA as “the benefits people obtain from ecosystems” (MEA 2003). They are generated by ecosystem functions, which are in turn underpinned by biophysical “supporting” structures and processes (de Groot et al. 2010). The benefits include material products of land such as food and freshwater, the regulation of natural hazards, maintenance of natural resources such as pure air and biodiversity, and cultural benefits linked to the meanings and values that people recognize to the ‘landscape’.

“The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity” initiative developed a global study on the economic value of ecosystem services (TEEB 2010), with a focused analysis on ecosystem services in agricultural systems (TEEB 2015).

17 The Multidimensional Benefits of Terraced Landscape … |

281 |

Classifications of ecosystem services include:

–Provisioning services defined as the material or energy outputs from ecosystems, which include food, water and other material resources;

–Regulation and maintenance services, which include the category of “supporting” or habitat services (such as habitats provided to species and the maintenance of genetic diversity), defined as the services that ecosystems provide by

acting as regulators e.g. regulating the quality of air and soil or by providing flood and disease control;

–Cultural services, which have a clear link with the landscape scale and human well-being (Chan et al. 2012; Milcu et al. 2013), defined as the immaterial benefits such as recreation and mental/physical health, well-being, aesthetic appreciation, spiritual experience and sense of place.

The link between ecosystem services, landscape and human well-being has been widely recognized in the scientific literature (Haines-Young and Potschin 2010; Iverson et al. 2014; Plieninger et al. 2014; Hicks et al. 2015). Many authors have stressed the need of integrate ES in landscape and territorial planning (de Groot et al. 2010; Hartel et al. 2014).

Key ecosystem services in terraced landscapes are identified in Table 17.2. The selection represents the ES that are more likely to be reduced as a consequence of land use change and land abandonment in terraced landscapes (Gravagnuolo 2014, 2015).

These ES can be evaluated in economic terms to assess the societal costs of their reduction or loss. The economic valuation of ES is necessary to support informed choices in the implementation of economic instruments, balancing conflicting interests between farmers and other providers of ES and the wide range of actual and potential beneficiaries.

Table 17.2 Key ecosystem multidimensional services in terraced landscapes

Categories (from MEA, |

Key ecosystem services in terraced landscapes |

TEEB) |

(adapted from Gravagnuolo 2014, 2015) |

Provisioning |

Food |

|

Freshwater |

Regulating and |

Moderation of extreme events (landslide, flooding, fire) |

maintenance |

Erosion prevention and maintenance of organic topsoil |

|

Maintenance of agro-biodiversity |

|

Local climate and air quality |

|

Control and mitigation of Invasive Alien Species |

|

Habitat for species |

Cultural |

Conservation of local knowledge, traditional farming and |

|

building techniques |

|

Cultural identity, spiritual experience and sense of place |

|

Tourism |

|

Recreation and mental and physical health |

|

Aesthetic appreciation |

282 |

L. Fusco Girard et al. |

17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

The economic valuation of ecosystem services has been experimented in many cultural agrarian landscapes (Nahuelhual et al. 2014; Gravagnuolo 2015; TEEB 2015); however, it “may not always be possible or meaningful, as they often render themselves better to qualification than to quantification, such as in the case of cultural services” (Gaitán-Cremaschi et al. 2017).

The theory of Total Economic Value defines the value of a cultural and/or ecological resource as the sum of its direct and indirect use values and its independent-of-use (non-use) values (Randall 1987). Economic valuation techniques differ for the estimation of the components of value (Defra 2007). Table 17.3 shows the main evaluation methods that can be applied for ES economic valuation.

The estimation of monetary value of cultural services should be carefully approached (Chan et al. 2012; Daniel et al. 2012; Winthrop 2014; Fish et al. 2016). If we adopt the notion of Complex Social Value of terraced landscapes, the Total Economic Value is enriched including qualitative and quantitative “measures” of value in multiple dimensions.

The notion of the Complex Social Value projects the traditional economic evaluations into a multidimensional space, where the consequences of economic choices are assessed in relation also to their environmental and sociocultural

Table 17.3 Components of Total Economic Value and evaluation methods in relation with ES categories (adapted from DEFRA 2007)

Category of |

Total Economic Value components |

|

|

|

ES |

Direct use value |

Indirect |

Option value |

Non-use values |

|

|

use value |

|

|

Provisioning |

Market-based |

– |

Stated preference |

– |

|

techniques |

|

methods (contingent |

|

|

|

|

valuation, choice |

|

|

|

|

modelling), benefit |

|

|

|

|

transfer |

|

Regulation |

– |

Avoided |

Stated preference |

Stated |

and |

|

cost |

methods (contingent |

preference |

maintenance |

|

method |

valuation, choice |

methods |

|

|

|

modelling), benefit |

(contingent |

|

|

|

transfer |

valuation, choice |

|

|

|

|

modelling) |

Cultural |

Incomes from tourism |

– |

Stated preference |

Stated |

|

and recreation activities, |

|

methods (contingent |

preference |

|

revealed preference |

|

valuation, choice |

methods |

|

methods (travel cost, |

|

modelling), benefit |

(contingent |

|

hedonic price) |

|

transfer |

valuation, choice |

|

|

|

|

modelling) |

17 The Multidimensional Benefits of Terraced Landscape … |

283 |

impacts. The economic value of ecosystem services in terraced landscapes represents thus an acceptable (under) estimation of their Complex Social Value for society, since it can include, even if partially, future generations. It should be integrated with non-economic indicators on well-being, health, etc. as far as possible.

The economic value of ES, and particularly cultural ES, should not be taken always as a “precise” estimate, but it can be used to discuss the applicability of economic instruments for land use management to preserve the multifunctionality of cultural agrarian landscapes, and to justify public interventions (e.g. incentives, grants).

17.2.4 Evaluation of Costs and Expected Flows of Benefits

The evaluation of costs and expected flows of benefits is a fundamental evaluation step to support informed policy choices and also private investments (FAO & Global Mechanism of the UNCCD 2015).

A careful stakeholder assessment must be performed, considering who pays for landscape recovery and maintenance (typically farmers) and who benefits—and how much—from the regeneration (e.g. tourism activities, tourists, service providers, residents, community at large). Ecosystem services should be assessed at their provision location, and in the territory in which beneficiaries are located.

Costs for terraced landscape regeneration can be classified into three main categories:

–Investment costs (recovery of abandoned land)

–Landscape maintenance costs (dry-stone wall maintenance, water channels and cisterns maintenance, other necessary periodic works)

–Operating costs (costs of conducting farms such as energy, materials, administrative services, etc.)

The traditional cost–benefit analysis (CBA) should be enriched with the ES assessment and stakeholder assessment (Hein et al. 2006; Darvill and Lindo 2016) in the perspective of a richer multidimensional Community Impact Evaluation (Lichfield 1996).

Terraced landscape regeneration represents a cost at the micro-level (farm business) and a benefit at the macro-level (societal benefits from ES). Possible economic instruments should be designed on careful evaluation of ES provision costs and benefits at the farm scale (business analysis) and at the territorial scale.

In the following section, we discuss the applicability of some economic instruments in terraced landscapes, with a view to successful cases of application in different cultural agrarian landscapes.