- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

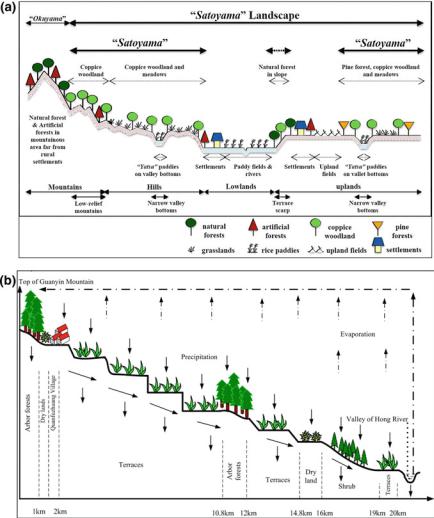

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

226 |

Y. Jiao et al. |

both the Hani terraces and the Satoyama are facing continuous pressures from social and economic development. Learning the efficient, adaptive management strategies from Satoyama can help Hani rice terraces meet the challenges.

14.1Introduction

Agricultural lands comprise about 40% of global terrestrial area (FAO 2009). Although its primary services are the provision of food, fiber, and fuel, agriculture— as an ecosystem directly managed by human beings—plays a unique role in both supplying and relying on ecosystem services (Swinton et al. 2007; MA 2005; Zhang et al. 2007). The links within the agricultural landscape, namely the landscape pattern and process, impact the ecosystem services provided to society (Matson et al. 1997). Thus, it is essential to assess agriculture’s ecosystem services from a landscape perspective (Tscharntke et al. 2005).

Rice is the most important irrigated crop in the world (FAO 2009). Due to the long history of rice cultivation in Asia, there are various kinds of traditional rice paddy landscapes that provide multiple ecosystem services to local people. Taking as study objects two traditional rice paddy/terrace landscapes in eastern Asia, the Satoyama in Japan and the Hani terrace landscape in southwest China, this article summarizes and analyzes the two areas’ characteristics and ecosystem services. The study’s aims are: (1) to compare the landscapes’ pattern and ecosystem services,

(2) to analyze the target and nontarget ecosystem services within and outside the landscapes, (3) to discuss the landscapes’ current status and the challenges they are facing, and (4) to find lessons learned from Satoyama that may benefit the sustainability of the Hani rice terraces.

14.2Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

The traditional Satoyama landscape is a mosaic of secondary forests (also called Satoyama forests), wet rice paddies, cultivated fields, grasslands, streams, ponds, and irrigation ditches surrounding a Japanese farming village—the entire landscape necessary to supplying the needs of a community (Fukamachi et al. 2001; Kobori and Primac 2003; Takeuchi et al. 2003). Because the Satoyama landscape is the traditional rural/agriculture landscape of Japan, its features exist on a national scale (Table 14.1), and the two most famous Satoyama landscapes are the rice paddies located in Noto Peninsula and Sado Island (Fig. 14.1).

The Hani terrace landscapes are composed of forests, ponds, villages, rice terraces inundated all year, and dry fields. They are located in the Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture, in the southeast part of Yunnan Province, southwestern

14 Comparative Studies on Pattern and Ecosystem Services … |

227 |

||

Table 14.1 Components and features of the Satoyama and the Hani terrace landscape |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Indicator |

Satoyama landscape |

Hani terrace landscape |

|

Location |

23°–45°N, 125°–142°E |

22.5°–23.5°N, 100°–103°E |

|

Spatial scale |

National/Japan |

County/Yuanyang, Lvchun, Jinping, |

|

|

|

Honghe |

|

Area (ha) |

6,000,000–9,000,000a |

1,112,300 |

|

Terrain |

From low-relief mountains to |

From high-relief mountain peak to |

|

|

hills, lowlands, and valley |

deep carved river valley, distributed |

|

|

bottoms |

across the whole mountainsides |

|

Climate |

Temperate monsoon |

Subtropical monsoon and vertical |

|

|

|

climate |

|

Total annual |

1000–2000 |

700–2400 |

|

precipitation |

|

|

|

(mm) |

|

|

|

Average |

10 |

17 |

|

temperature (° |

|

|

|

C) |

|

|

|

Elevation range |

175–195 |

105–2940 |

|

(m-a.s.l.) |

|

|

|

History |

Yayoi era (300 B.C.*A.D. 300) |

Tang dynasty (A.D. 618*903) |

|

Landscape |

Satoyama woodlands, other crop |

Natural and secondary forests, |

|

composition |

fields, grasslands, wet rice |

year-round inundated rice terraces, |

|

|

paddies, villages, streams, |

dry fields, grasslands, villages, |

|

|

reservoirs, artificial ponds, |

streams, numerous artificial small |

|

|

irrigation ditches |

terraced ponds, and irrigation ditches |

|

Area proportion |

Forests: paddies: other crop |

Forests: terraces: dry lands: other |

|

of landscape |

fields = 1:1:1 at village scaleb |

land uses = 3:1:2:1 at county scale |

|

composition |

|

(Yuanyang) |

|

Current status |

Abandoned and underused since |

Mostly are kept in original status |

|

|

1960s |

|

|

aCited from Takeuchi et al. (2003, p. 46) |

|

|

|

bCited from Washitani (2001) |

|

|

|

China (Fig. 14.1). People of various races, with the Hani people being the main ethnic group, have maintained this spectacular agricultural landscape for over 1300 years (Table 14.1). Compared to the Satoyama landscape, the Hani terrace landscapes are concentrated in this specific bio-cultural region. They are a unique traditional agricultural land use system in the high-relief mountainous region with a subtropical monsoon climate.

Both the Satoyama and Hani landscapes are traditional subsistence farming systems, which provide a bundle of ecosystem services (Takeuchi 2010; Jiao et al. 2012), including provisioning services (species used as food sources, timber, medicines, and other useful products); regulating services (flood control, climate stabilization); supporting services (soil formation, water purification); and cultural services (aesthetic or recreational assets, such as ecotourism attractions, providing tangible and intangible benefits) (Kremen and Ostfeld 2005). In addition,

228 |

Y. Jiao et al. |

Fig. 14.1 Location of the Satoyama in Japan and the Hani terrace landscape in SW China

both landscapes are facing serious challenges on local and global scales, although these challenges differ in natural and social respects. For example, owing to economic globalization and the aging of local farmers, the Satoyama landscape was underused or abandoned, which caused a decrease in bio-cultural diversity. On the contrary, the Hani terrace landscape is under high pressure to develop economically because of the poverty of local farmers and underdeveloped socioeconomic conditions. In this circumstance, it may be argued that the Hani terrace landscape is in the early overuse stage that the Satoyama landscape faced before the 1960s.

14.3Spatial Pattern and Ecological Process

in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

Landscape pattern—the spatial arrangement of ecosystems—can influence the horizontal and vertical flows of materials, such as water, sediments, or nutrients (Peterjohn and Correll 1984), and other important ecological processes, such as net primary production (Turner 1989). Therefore, landscape pattern can affect the spatial distribution and delivery of ecosystem services. The center of the Satoyama landscape is the settlement surrounded by small, gently sloping rice paddies, and large areas of secondary forests (Fig. 14.2a). All the ecosystems or elements in the

14 Comparative Studies on Pattern and Ecosystem Services … |

229 |

Fig. 14.2 Spatial structure from high mountains to river valley with strongly connected elements in a the Satoyama landscape (after Yamamoto 2001, from Takeuchi et al. 2003) and b the Hani terrace landscape

Satoyama landscape were once strongly connected to each other through the agricultural land use system (Takeuchi et al. 2003), mainly via organic fertilizers, such as manure, fodder, ash, and forest litter.

The Hani terrace landscape stretches across the whole mountain slope, with the natural forests on the mountaintops as one major landscape element (Fig. 14.2b). The forest-village-terraces structure along the Hani landscape’s slope forms an efficient resource circulation system. The water from the forests runs through an