- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

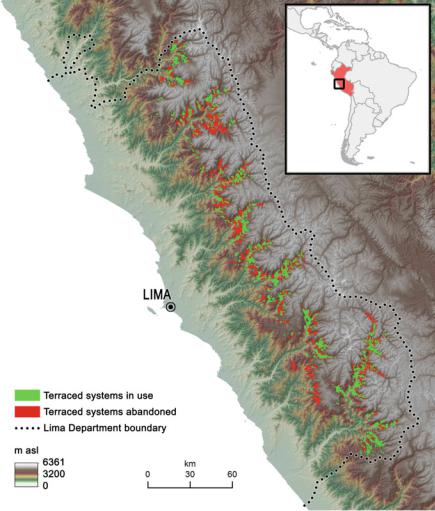

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

120 |

L. Camara and M. B. de Mesquita |

8.1Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

Peru has vast terraced areas, and, since the 1980s, an attempt has been made to identify and develop an inventory of the terraced system. In 1982, Masson (1994) estimated one million hectares of terraces. That figure is based on the natural resource inventories and evaluations developed by ONERN (Oficina Nacional de Evaluación de Recursos Naturales; National Office for the Evaluation of Natural Resources) between 1968 and 1982 on the western side of the Andes. ONERN’s goal was knowledge of the conservation status of terraced surfaces, but it should be emphasized that ONERN published neither the survey nor an official cartography of functional and abandoned terraces.

In 1996, INRENA (Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales; National Institute of Natural Resources) determined the existence of 256,945 ha of pre-Hispanic terraces in eight Peruvian regions. Until recently, no other national inventory had been conducted.

However, in 2010, AgroRural led the initiative. AgroRural (the Rural Agricultural Productive Development Program) is part of the Ministry of Agriculture, and it initiated a major project to inventory and characterize the agricultural terraces of 95 municipalities in 11 Peruvian regions. The municipalities were selected via several indicators: the presence of at least 50–200 terraced hectares, which justifies structural intervention for water access; the importance of the municipality itself and the role it plays within the province; the farmers’ willingness to work on terraces; communication mechanisms between the municipality and markets; and the presence of municipal, rather than private, land. This latter indicator was considered because community work is more beneficial to the population than individual labor, which requires a larger workforce.

Operating along the Andes Mountains, the AgroRural project aims to gather a base of territorial knowledge, develop innovative technologies, and implement recovery interventions—promoting a large-scale territorial transformation. Fundamentally, the objective is coordinating social and institutional strategies to develop a recovery program for specific areas (micro-basins). These micro-basins can be the subjects of a basic pilot program—studying them, developing investment programs and public policies to recover abandoned terraces, and harnessing the terraces’ potential to counteract the effects climate change has on agricultural production.

The AgroRural inventory has attempted to document areas with the highest concentration of terraces regionally. The program’s objective is not to detect and describe all terraced areas, but, rather, to document maximum production capacity and the possibility of socio-economic investment returns.

As shown in Table 8.1, AgroRural’s systematization and inventory of agricultural terraces has cataloged 340,719.11 terraced hectares, of which 259,319.04 are in use and 81,400.06 abandoned. AgroRural also estimates another 150,000 ha of

8 Terraced Landscapes in Perù: Terraces and Social Water Management |

121 |

||||

Table 8.1 Inventory of |

|

|

|

|

|

Region |

State of terraces |

Total (ha) |

|||

terraced areas in Peru |

|||||

|

In use (ha) |

Abandoned (ha) |

|

||

|

|

|

|||

|

Cusco |

43,273.09 |

16,029.81 |

59,302.90 |

|

|

Lima |

35,066.91 |

20,927.97 |

55,994.89 |

|

|

Ayacucho |

36,655.33 |

9723.89 |

46,379.22 |

|

|

Apurimac |

30,652.48 |

13,475.02 |

44,127.50 |

|

|

Arequipa |

35,276.36 |

7680.05 |

42,956.41 |

|

|

Puno |

20,705.62 |

2828.65 |

23,534.27 |

|

|

Huancavelica |

17,634.44 |

4244.55 |

21,878.99 |

|

|

Tacna |

11,174.67 |

2709.33 |

13,884.00 |

|

|

Moquegua |

11,247.23 |

1739.77 |

12,987.01 |

|

|

Amazonas |

11,121.77 |

539.68 |

11,661.44 |

|

|

Junin |

6511.13 |

1501.34 |

8012.48 |

|

|

Total |

259,319.04 |

81,400.06 |

340,719.11 |

|

|

Source Eguren and Marapi (2014) |

|

|||

terraces that were not included in the program. This report concludes that the regions with the most terraced hectares are Cusco, Lima, and Ayacucho.

Considering the municipalities involved in the program and fieldwork in different communities of four regions, the altimetry of densely terraced areas can be identified.1 Most of the inter-Andean valleys are between 2500 and 4000 m above sea level. The terraced areas corresponding to the lowest altitudes (2300–3500 m) are the best preserved and used for agricultural production, as can be seen in Fig. 8.1. The terraces of Andamarca in the Ayacucho region are located at an altitude ranging from 3100 to 3400 m. Terraces higher than 3500 m are usually abandoned and, in a few cases, are covered by weeds and small shrubs.

The terraces at 2500–3500 m have a temperate climate, support a wide variety of crops, and have a vegetative cover of greater intensity than the higher terraces. In addition, irrigation facilities (canals, springs, lagoons, wetlands, etc.) are wellconserved, and rainfall is more regular, ranging from 500 to 1000 mm per year.2 The clivometric profile has very accentuated values, ranging between 15 and 75%. Among the terraces with slopes up to 50%, cultivable surfaces can have an area of up to 30 m, and wall heights vary from 1 to 4 m. Slopes above 70% show a decrease in the average surface of the embankments up to a maximum of 2.0 m, and

wall heights vary from 2.5 to 10 m.

Terrace crops are characterized by a high degree of biological diversity and vary according to the altitude. Many species and varieties are cultivated: grains and

1Because AgroRural has not published its full study, the data analyzed here are the result of the author’s field experience reconnaissance.

2SENAMHI (2009)

122 |

L. Camara and M. B. de Mesquita |

Fig. 8.1 Well-preserved terracing in Andamarca. Photo L. Camara

cereals, legumes, tubers, vegetables and spices, fruits, fruit trees, native trees, etc. (Tovar 1995; Tapia and Fries 2007). An important aspect of agronomic knowledge is crop management—optimizing sowing and harvesting, developing specific methods of conservation and soil fertilization, choosing cultivable varieties, and understanding the available technologies.

The mechanisms regulating soil fertility in the Andes are modulated by many variables—climatic, altimetric, pedological, topographic, crop intensity, etc. Farmers in the area practice crop rotation and cultivate different types of plants in the same terrace to encourage a symbiotic relationship between the crops—feeding, not just the harvest, but also the land. Such mechanisms imitate nature by diversifying plant species. In most agricultural systems, both practices combine to ensure biodiversity.

Most farmers grow 12–15 plots regularly and others on rotation. Crop distribution is extremely heterogenous. Some fields have only one crop, others more, sometimes in alternating rows, often cultivated in small plots of 20–25 m2 with 30– 40 different cultivars. Some may even have 100 different cultivars, thanks to a socially regulated exchange. This heterogeneity involves continuous experimentation, not only to avoid risks, but, above all, to create new varieties; this favors hybridization and crossbreeding between different crops. The local varieties, in fact, are most suited for the climate and the soil, and they express their best potential in the territory where they have acclimated over the centuries. For this reason, they are

8 Terraced Landscapes in Perù: Terraces and Social Water Management |

123 |

more resistant and require less external interventions. They are, therefore, more sustainable, both from an environmental and an economic point of view. In this sense, biodiversity is confirmed a unique and precious heritage: genetic but also cultural, social, and economic.

The following map (Fig. 8.2), elaborated with AgroRural’s data, shows the regional distribution of terracing in the Lima region. Mostly, Lima has a high percentage of abandoned areas respect to inventory, most of them are also uncultivated lands or difficult to define. One of the causes is the emigration trends. For example, in 23 of 33 municipalities in the province of Yauyos the population does

Fig. 8.2 Terraced areas in Lima region (elaborated by Francesco Ferrarese and Lianet Camara on data provided by AgroRural)