Lesson topic №26. Фибрилляция предсердий (Atrial Fibrillation)

.pdfFor certain patients with recurrent paroxysmal atrial fibrillation who also can identify its onset by symptoms, some clinicians provide a single oral loading dose of flecainide (300 mg for patients ≥ 70 kg, otherwise 200 mg) or propafenone (600 mg for patients ≥ 70 kg, otherwise 450 mg) that patients carry and self-administer when palpitations develop (“pill-in-the-pocket” approach).

This approach must be limited to patients who have no sinoatrial or AV node dysfunction, bundle branch block, QT prolongation, Brugada syndrome, or structural heart disease. Its hazard (estimated at 1%) is the possibility of converting atrial fibrillation to a slowish atrial flutter that conducts 1:1 in the 200 to 240 beat/minute range.

This potential complication can be reduced in frequency by coadministration of an AV nodal suppressing drug (eg, a betablocker or a nondihydropyridine calcium antagonist).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and aldosterone blockers may attenuate the myocardial fibrosis that provides a substrate for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure, but the role of these drugs in routine atrial fibrillation treatment has yet to be defined.

Ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation

For patients who do not respond to or cannot take rate-controlling medications, ablation of the AV node may be done to cause complete heart block;

insertion of a permanent pacemaker is then necessary.

Ablation of only one AV nodal pathway (AV node modification) reduces the number of atrial impulses reaching the ventricles and eliminates the need for a pacemaker, but this approach is considered less effective than complete ablation and is rarely used.

Ablation procedures that accomplish electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins from the left atrium can prevent atrial fibrillation without causing AV block.

In comparison to other ablation procedures, pulmonary vein isolation has a lower success rate (60 to 80%) and a higher complication rate (1 to 5%).

Accordingly, this procedure is often reserved for the best candidates (eg, younger patients who have no significant structural heart disease, patients without other options such as those with medication-resistant AF, or patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure.

Randomized clinical trials addressing the need for continued long-term oral anticoagulation after an apparently successful ablation procedure are underway.

Prevention of thromboembolism

Prevention of thromboembolism is an important goal in the treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation.

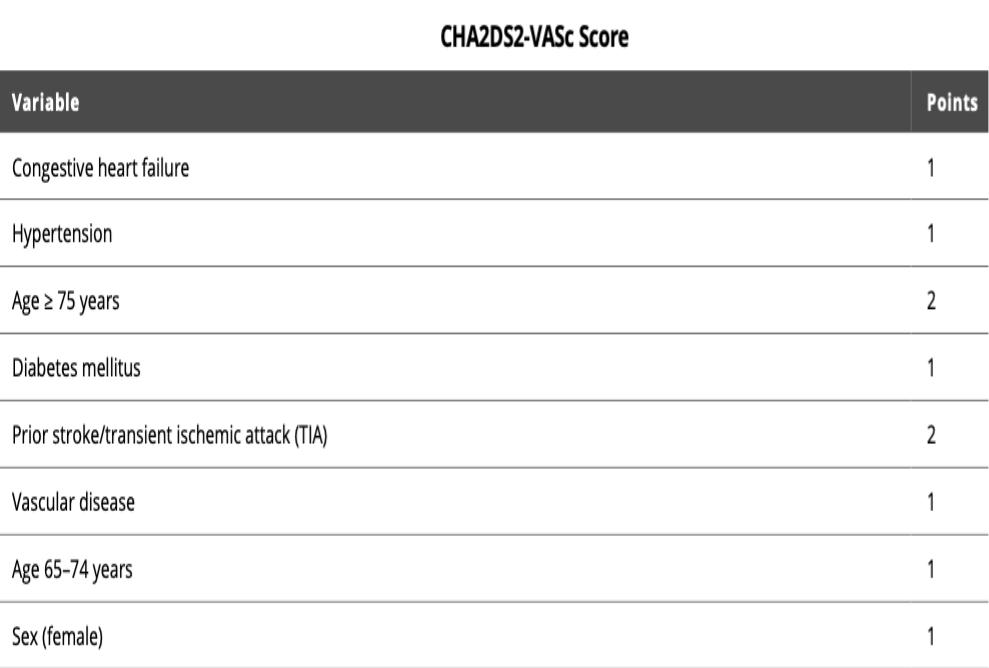

Current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommend use of the CHA2DS2VASc score and specific cardiac factors to guide thromboembolic therapy.

Long-term measures to prevent thromboembolism are taken for certain patients with atrial fibrillation depending on their estimated risk of stroke versus risk of bleeding (eg, as per the CHA2DS2-VASc score and the HAS-BLED tool).

Conversion of atrial fibrillation with either an antiarrhythmic drug or with DC cardioversion conveys a higher risk for thromboembolic events.

When a patient with atrial fibrillation who is not anticoagulated is to undergo cardioversion additional considerations are required.

If urgent cardioversion is required because of hemodynamic compromise, cardioversion is done and anticoagulation is started as soon as is practical and continued for at least 4 weeks.

If the onset of the current episode of atrial fibrillation is clearly within 48 hours, cardioversion may proceed without prior or subsequent anticoagulation in men with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 and in women with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 (class IIb recommendation).

If the onset of the current episode of atrial fibrillation is not clearly within 48 hours, the patient should be anticoagulated for 3 weeks before and at least 4 weeks after cardioversion regardless of the patient's predicted risk of a thromboembolic event (class I recommendation).

Alternatively, therapeutic anticoagulation is started, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is done, and, if no left atrial or left atrial appendage clot is seen, cardioversion may be done, followed by at least 4 weeks of anticoagulation therapy (class IIa recommendation).

Current guidelines

The guidelines for antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation differ in different regions. The current guidelines in the United States are as follows:

•Long-term oral anticoagulant therapy is recommended for patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical artificial heart valve, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with CHA2DS2-VASc scores of ≥ 2 in men and ≥ 3 in women (class of recommendation I) and may be considered for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and CHA2DS2-VASc scores of ≥ 1 in men and ≥ 2 in women (class of recommendation IIb).

•No antithrombotic therapy is recommended for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 0 in men and 1 in women (class of recommendation IIa).

•Patients with atrial fibrillation and a mechanical heart valve(s) are treated with warfarin.

•Patients with atrial fibrillation and significant mitral stenosis are treated with warfarin.

For patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who are to be treated with an oral anticoagulant, a class I recommendation is given for warfarin with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0 to

3.0, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

For patients eligible for anticoagulant therapy with either a vitamin K antagonist anticoagulant, such as warfarin, or a non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulant such as apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban, the non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants are preferred (class I recommendation).

These general guidelines are altered in patients with more than moderate renal impairment.

The left atrial appendage may be surgically ligated or closed with a transcatheter device when appropriate antithrombotic therapy is absolutely contraindicated.

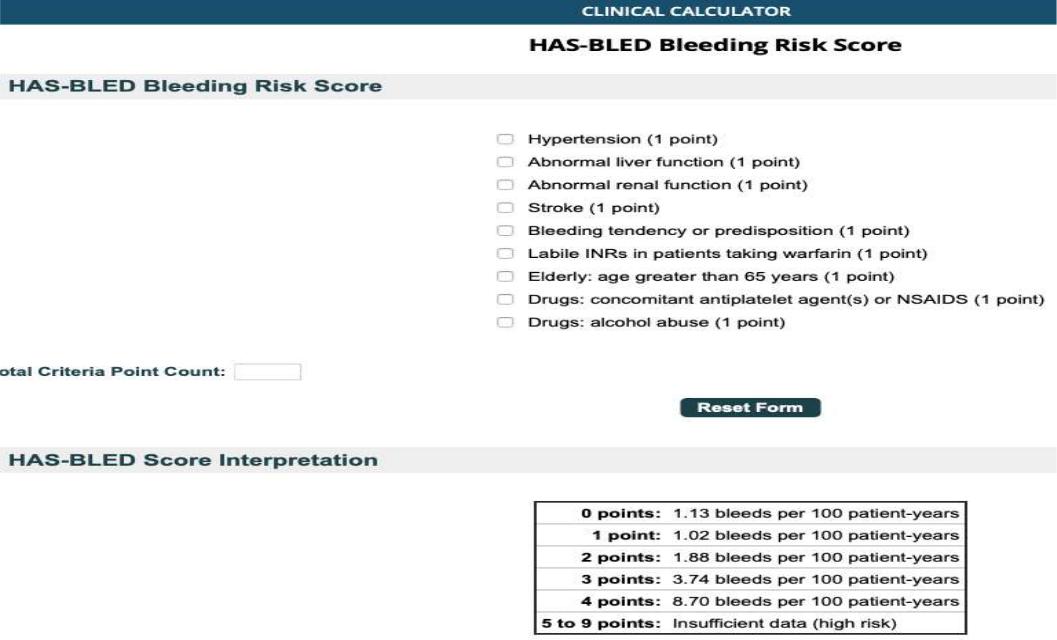

An individual patient's risk of bleeding may be estimated with any of a number of prognostic tools, of which the most commonly used is HAS-BLED

(see table HAS-BLED Tool for Predicting Risk of Bleeding in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation).

The HAS-BLED score serves best in identifying conditions that, if modified, reduce bleeding risk rather than in identifying patients with a higher risk of bleeding who should not receive anticoagulation.