Сборник текстов по психологии для чтения на английском языке с упражнениями Г.В. Бочарова, М.Г. Степанова

.pdfT e x t 9

EXTREME STRESS

Sources of Extreme Stress

Extreme stress has a variety of sources, ranging from unemployment to wartime combat, from violent natural disaster to rape. Extreme stress marks a radical departure from everyday life, such that a person cannot carry on as before and, in some cases, never fully recovers. What are some major stressors? What effect do they have on people? How do people cope?

Unemployment and Underemployment

Joblessness is a major source of stress. When the jobless rate rises, so do first admissions to psychiatric hospitals, infant mortality, deaths from heart disease, alcohol related diseases, and suicide. “Things just fell apart,” one worker said after both he and his wife lost their jobs. People usually react to the stress of unemployment in several stages. First comes a period of relaxation and relief, in which they take a vacation of sorts, confident they will find another job. Stage 2, marked by continued optimism, is a time of concentrated job hunting. In Stage 3, a period of vacillation and doubt, jobless people become moody, their relationships with family and friends deteriorate, and they scarcely bother to look for work. By Stage 4, a period of malaise and cynicism, they have simply given up. Although these effects are not universal, they are quite common. Moreover, there are indications that joblessness may not so much create new psychological difficulties as bring preciously hidden ones to the surface. Two studies have shown that death rates go up and psychiatric symptoms worsen not just during periods of unemployment but also during short, rapid upturns in the economy. This finding lends support to the point we discussed earlier that change, whether good or bad, causes stress.

Even among people who are employed, status on the job — where they stand in their company’s occupational hierarchy — affects health.

141

Common sense holds that high powered tycoons are especially likely to die suddenly of a heart attack. In reality, the reverse is true: On average, high level executives live longer than messengers and mailroom clerks.

Divorce and Separation

As Coleman and colleagues (1987) observe, “the deterioration or ending of an intimate relationship is one of the more potent of stressors and one of the more frequent reasons why people seek psychotherapy.” After a breakup, both partners often feel they have failed at one of life’s most important endeavors. Strong emotional ties frequently continue to bind the pair. If only one spouse wants to end the marriage, the one initiating the divorce may feel sadness and guilt at hurting a once loved partner, and the rejected spouse may vacillate between anger, humiliation, and self recrimination over his or her role in the failure. Even if the decision to separate was mutual, ambivalent feelings of love and hate can make life upsetting and turbulent. Adults are not the only ones who are stressed by divorce, of course. A national survey of the impact of divorce on children found that a majority suffer intense emotional stress at the time of divorce; although most recover within a year or two (especially if the custodial parent establishes a stable home and their parents do not fight about child rearing), a minority experience long term problems.

Bereavement

For decades it was widely held that following the death of a loved one, people go through a necessary period of intense grief during which they work through their loss and, about a year later, pick up and go on with their lives. Psychologists and physicians as well as the public at large have endorsed this cultural wisdom. But Wortman and others have challenged this view on the basis of their own research and reviews of the literature on loss.

According to Wortman, the first myth about bereavement is that people should be intensely distressed when a loved one dies, which suggests that people who are not devastated are behaving abnormally, perhaps pathologically. Often, however, people have prepared for the

142

loss, said their goodbyes, and feel little remorse or regret; indeed, they may be relieved that their loved one is no longer suffering. The second myth — that people need to work through their grief — may lead family, friends, and even physicians to consciously or unconsciously encourage the bereaved to feel or act distraught. Moreover, physicians may deny those mourners who are deeply disturbed needed antianxiety or antidepressant medication “for their own good.” The third myth holds that people who find meaning in the death, who come to a spiritual or existential understanding of why it happened, cope better than those who do not. In reality, people who do not seek greater understanding are the best adjusted and least depressed. The fourth myth — that people should recover from a loss within a year or so — is perhaps the most damaging. Parents trying to cope with the death of an infant and adults whose spouse or child died suddenly in a vehicle accident continue to experience painful memories and wrestle with depression years after. But because they have not recovered “on schedule,” members of their social network may become unsympathetic. Hence, the people who need support most may hide their feelings because they do not want to make other people uncomfortable and fail to seek treatment because they, too, believe they should recover on their own.

Not all psychologists agree with this “new” view of bereavement. But most agree that research on loss must take into account individual (and group or cultural) differences, as well as variations in the circumstances surrounding a loss.

Catastrophes

Catastrophes include floods, earthquakes, violent storms, fires, and plane crashes. Psychological reactions to all these stressful events have much in common. At first, in the shock stage, “the victim is stunned, dazed, and apathetic,” and sometimes even “stuporous, disoriented, and amnesic for the traumatic event.” Then, in the suggestible stage, victims are passive and quite ready to do whatever rescuers tell them to do. In the third phase, the recovery stage, victims regain emotional balance, but anxiety often persists; and they may need to recount their experiences over and over again. Some investigators report that in later stages survivors may feel irrationally guilty because they lived while others died.

143

Combat and Other Threatening Personal Attacks

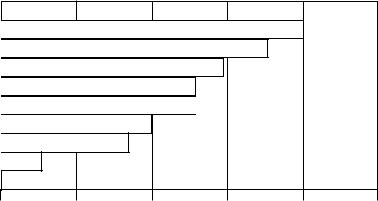

Wartime experiences often cause soldiers intense and disabling combat stress that persists long after they have left the battlefield. Similar reactions — including bursting into rage over harmless remarks, sleep disturbances, cringing at sudden loud noises, psychological confusion, uncontrollable crying, and silently staring into space for long periods — are also frequently seen in survivors of serious accidents, especially children, and of violent crimes such as rapes and muggings. Figure below shows the traumatic effects of war on the civilian population, based on composite statistics obtained after recent civil wars. Rates of clinical depression and post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are around 50 percent, whereas rates of even 10 percent would be consider ed high in a normal community.

Mental trauma in societies at war

In societies that have undergone the stress of war, nearly everyone suffers some psychological reaction, ranging from serious mental illness to feelings of demoralization. Rates of clinical depression are as high as 50 percent.

123456789012345678901234567890

12345678901234567890123456789 0

12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901

1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890 1

1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890 1

12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901

123456789012345678901 2

1234567890123456789012

23456789012345678901234567890121234567

12345678901234567890123456789012123456

12345678901234567890123456789012123456

12345678901234567890123456789012123456

234567890123456789012345678 9

234567890123456789012345678 9

2345678901234567890123456789

2345678901234567890123456789012123

234567890123456789012345678901212

234567890123456789012345678901212

234567890123456789012345678901212

12345678901232345678901234567 90123456789012123

123456789012 3

123456789

12345678

12345678

123456789

0 |

20 |

40 |

60 |

80 |

100 |

144

2Demoralization

234

2323 44 Physical and mental exhaustion

2Seeking justice/revenge

234

2323 44 Fear of goverement

12 Clinical depression/PTSD

12

234

234 Serious family conflict

234

2Psychiatric incapacitation

234

23 4 Serious mental illness

234

I. Choose the word from the box to match the definition on the left.

Combat |

Unemployment |

Catastrophe |

|

Separation |

Bereavement |

Underemployment |

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Deprivation, particularly the loss |

______________________ |

|

|

by death. |

|

|

2. |

Half time; the job which does not |

______________________ |

|

|

correspond to the worker’s |

|

|

|

qualification. |

|

|

3. |

The cessation of conjugal cohabi |

______________________ |

|

|

tation of husband and wife; |

|

|

|

the state of being disconnected. |

|

|

4.Lack of employment; joblessness. ______________________

5.Fighting between organized forces, ______________________

as the military or between indivi duals; a battle or skirmish in war; a struggle; a conflict.

6.A wide spread disastrous event; any ______________________

overwhelming misfortune or failure.

145

II. Answer the questions to the text.

1.What are the sources of extreme stress?

2.How do people react to the stress of unemployment?

3.Is divorce stressful only to the partners involved?

4.What are the four myths about bereavement according to Wortman?

5.What should be taken into account while researching the bereavement?

6.What are the stages of psychological reactions of people to the stressful events?

7.What reactions are frequently seen in survivors of serious accidents?

8.What are the traumatic effects of war on the civilian population?

9.What is the rate of post traumatic stress?

10.Is 10 percent rate of PTSD considered high or low in a normal community?

III.Choose the facts to prove that:

1.Joblessness is a major source of stress.

2.Separation is “one of the more potent of stressors and one of the more frequent reasons why people seek psychotherapy.”

3.People do not necessarily go through a period of intense grief after the death of a loved one for about a year.

4.Wartime experiences cause intense and disabling combat stress.

T e x t 10

EFFECTIVENESS OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

What type of therapy is most effective for depression?

The various therapies we have discussed so far all share one characteristic: All are psychotherapies — that is, they use psychological

146

methods to treat disorders. But is psychotherapy effective? Is it any better than no treatment at all? And if it is, how much better is it?

Does Psychotherapy Work?

One of the first investigators to raise questions about the effective ness of psychotherapy was the British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1952). After surveying 19 published reports covering more than 7,000 cases, Eysenck concluded that therapy significantly helped about two out of every three people. However, he also concluded that “Roughly two thirds of a group of neurotic patients will recover or improve to a marked extent within about two years of the onset of their illness whether they are treated by means of psychotherapy or not.” Eysenck’s conclusion that individual psychotherapy was no more effective in treating neurotic disorders than no therapy at all caused a storm of controversy in the psychological community and stimulated conside rable research.

Ironically, an important but often overlooked aspect of the subsequent debate has little to do with the effectiveness of therapy but rather with the effectiveness of no therapy. Many researchers then and today agree with Eysenck that therapy helps about two thirds of the people who undergo it. More controversial is the question of what happens to people with psychological problems who do not receive formal therapy — is it really true that two thirds will improve anyway? Bergin and Lambert (1978) questioned the “spontaneous recovery” rate of the control subjects in the studies Eysenck surveyed. They concluded that only about one out of every three people improves without treatment (not the two out of three cited by Eysenck). Since twice as many people improve with formal therapy, therapy is indeed more effective than no treatment at all. Furthermore, these researchers noted that many people who do not receive formal therapy get real therapeutic help from friends, clergy, physicians, and teachers; thus, it is possible that the recovery rate for people who receive no therapeutic help at all is even less than one third.

Other attempts to study the effectiveness of psychotherapy have averaged the results of a large number of individual studies. The general

147

consensus among these studies is also that psychotherapy is effective, although its value appears to be related to a number of other factors. For instance, psychotherapy works best for relatively mild compared to more severe disorders and seems to provide the greatest benefits to people who really want to change.

Finally, one very extensive study designed to evaluate the effective ness of psychotherapy was reported by Consumer Reports (1995). Largely under the direction of psychologist Martin E.P.Seligman, this inves tigation surveyed 180,000 Consumer Reports subscribers on everything from automobiles to mental health. Approximately 7,000 people from the total sample responded to the mental health section of the question naire that assessed satisfaction and improvement in people who had received psychotherapy.

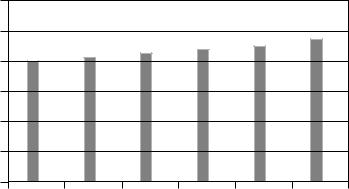

In reviewing the results of this study, Saligman (1995) summa rized a few of its most important findings. First, the vast majority of respondents reported significant overall improvement following therapy. Approximately 90 percent of the people who reported feeling very poor or fairly poor prior to therapy reported feeling very good, good, or so so following therapy. Second, there was no difference in the overall improvement score for people who had received therapy alone and those who had combined psychotherapy with medication. Third, no differences were found between the various forms of psychotherapy. Fourth, no differences in effecti veness were indicated between psychologists, psychiatrists, and so cial workers, although marriage counselors were seen as less effec tive. And fifth, people who had received long term therapy reported more improvement than those who had received short term therapy. This last result, one of the most striking findings of the study, is illustrated in the Figure below.

The Consumer Reports study lacked the scientific rigor of more traditional investigations designed to assess psychotherapeutic efficacy. For example, it did not use a control group to assess change in people who did not receive therapy. Nevertheless, it provides broad support for the idea that psychotherapy does work.

148

Duration of therapy and improvement

One of the most dramatic results of the Consumer Reports (1995) study on the effectiveness of psychotherapy was the strong relationship between reported improvement and the duration of therapy.

|

300 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

250 |

|

|

|

|

|

score |

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improvement |

150 |

|

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 months |

1—2 |

3—6 |

7—11 |

1—2 years |

>2 years |

|

|

months |

months |

months |

|

|

Duration of treatment

Which Type of Therapy Is Best for Which Disorder?

We have seen that researchers generally agree that psychotherapy is usually effective. This raises a second question: Is any particular form of psychotherapy more effective that the others? Is behavior therapy, for example, more effective than insight therapy? In general, the answer seems to be “not much.” Most of the benefit of treatment seems to come from being in some kind of therapy, regardless of the particular type.

The various forms of psychotherapy are based on different views of the causes of mental disorders, and at least on the surface, they approach the treatment of mental disorders very differently. So how can they all be equally effective? To answer this question, some psychologists have focused their attention on what the various forms of psychotherapy have in common, rather than emphasizing their differences.

149

First, all forms of psychotherapy provide people with an explanation for their problems.

Along with the explanation often comes a new perspective, providing the people with specific actions to help them cope more effectively. Second, most forms of psychotherapy offer hope. Because most people who seek therapy have low self esteem and feel demorali zed and depressed, hope and the expectation for improvement increases their feelings of self worth. And third, all major types of psychotherapy engage the client in a therapeutic alliance with the therapist. Despite differing therapeutic approaches, effective therapists are warm, empathetic, and caring people who understand the importance of establishing a strong emotional bond with their clients built on mutual respect and understanding. Together, these nonspecific factors, which are common to all forms of psychotherapy, appear at least in part to account for why most people who receive therapy show some benefits compared to those who receive no therapeutic help at all.

Still, some kinds of psychotherapy seem to be particularly appro priate for certain people and for certain types of problems. Insight the rapy, for example, seems to be best suited to people seeking profound self understanding, relief of inner conflict and anxiety, or better re lationships with others. Behavior therapy is apparently most appropriate for treating specific anxieties or other well defined behavioral problems such as sexual dysfunctions. Family therapy is generally more effective than individual counseling for the treatment of drug abuse. Cognitive therapies have been shown to be effective treatments for depression and seem to be a promising treatment for anxiety disorders as well.

To assist psychologists in selecting the most effective treatment methods, the Clinical Division of the American Psychological Asso ciation (1995) appointed the Task Force on Psychological Intervention Guidelines to review the scientific literature and develop a list of treat ments shown to be effective through controlled research. This list of empirically supported therapies, or ESTs, is designed to help therapists decide on the most appropriate therapy for a specific disorder. Since its publication, many psychologists have advanced the position that these therapies should be emphasized over those with less or no empirical support, particularly in training programs for clinical psychologists. The race, culture, ethnic background, and gender of both client and therapist can also influence which therapy is effective.

150