|

|

|

CHAPTER 30 |

Short-Term Financial Planning |

861 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

First |

Second |

Third |

Fourth |

|

||||||||

|

|

|

Quarter |

Quarter |

Quarter |

Quarter |

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources of cash: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Collections on accounts receivable |

85 |

|

80.3 |

|

108.5 |

128 |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Other |

|

0 |

|

|

0 |

|

|

12.5 |

0 |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total sources |

|

85 |

|

|

80.3 |

|

121 |

|

128 |

|

|

|

||

|

Uses of cash: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Payments on accounts payable |

65 |

|

60 |

|

55 |

|

50 |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Labor, administrative, and other expenses |

30 |

|

30 |

|

30 |

|

30 |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Capital expenditures |

32.5 |

1.3 |

|

5.5 |

8 |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Taxes, interest, and dividends |

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

4.5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

Total uses |

131.5 |

95.3 |

|

95 |

|

93 |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

Sources minus uses |

46.5 |

15.0 |

26 |

35 |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calculation of short-term financing requirement: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Cash at start of period |

5 |

|

41.5 |

56.5 |

30.5 |

|

|||||||||

2. |

Change in cash balance (sources less uses) |

46.5 |

15.0 |

26 |

35 |

|

||||||||||

3. |

Cash at end of period* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 2 3 |

41.5 |

56.5 |

30.5 |

|

4.5 |

|

||||||||

4. |

Minimum operating cash balance |

5 |

|

5 |

|

5 |

|

5 |

|

|

|

|||||

5. |

Cumulative short-term financing required† |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 4 3 |

46.5 |

61.5 |

|

35.5 |

.5 |

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

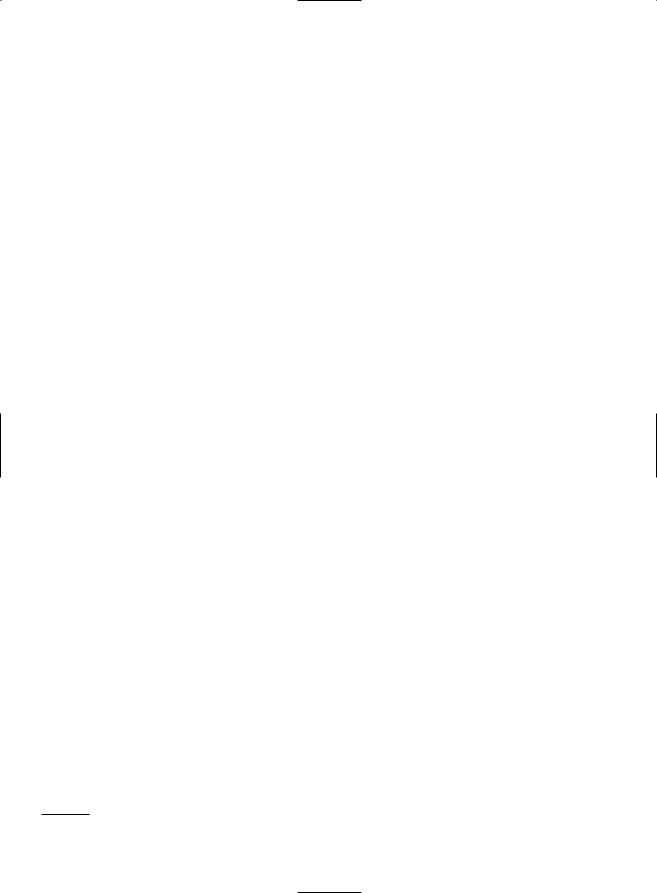

T A B L E 3 0 . 8

Dynamic Mattress’s cash budget for 2002 (figures in $ millions).

*Of course, firms cannot literally hold a negative amount of cash. This is the amount the firm will have to raise to pay its bills.

†A negative sign would indicate a cash surplus. But in this example the firm must raise cash for all quarters.

source, because by stretching they lose discounts given to firms that pay promptly. This is discussed in more detail in Section 32.1.

2.Labor, administrative, and other expenses. This category includes all other regular business expenses.

3.Capital expenditures. Note that Dynamic Mattress plans a major capital outlay in the first quarter.

4.Taxes, interest, and dividend payments. This includes interest on presently outstanding long-term debt but does not include interest on any additional borrowing to meet cash requirements in 2002. At this stage in the analysis, Dynamic does not know how much it will have to borrow, or whether it will have to borrow at all.

The forecasted net inflow of cash (sources minus uses) is shown in the box in Table 30.8. Note the large negative figure for the first quarter: a $46.5 million forecasted outflow. There is a smaller forecasted outflow in the second quarter, and then substantial cash inflows in the second half of the year.

The bottom part of Table 30.8 (below the box) calculates how much financing Dynamic will have to raise if its cash-flow forecasts are right. It starts the year with $5 million in cash. There is a $46.5 million cash outflow in the first quarter, and so Dynamic will have to obtain at least $46.5 5 $41.5 million of additional financing.

CHAPTER 30 Short-Term Financial Planning |

865 |

term financing may reflect a preference for ultimately financing the investment with retained earnings.

5.Perhaps the firm’s operating and investment plans can be adjusted to make the short-term financing problem easier. Is there any easy way of deferring the first quarter’s large cash outflow? For example, suppose that the large capital investment in the first quarter is for new mattress-stuffing machines to be delivered and installed in the first half of the year. The new machines are not scheduled to be ready for full-scale use until August. Perhaps the machine manufacturer could be persuaded to accept 60 percent of the purchase price on delivery and 40 percent when the machines are installed and operating satisfactorily.

6.Dynamic may also be able to release cash by reducing the level of other current assets. For example, it could reduce receivables by getting tough with customers who are late paying their bills. (The cost is that in the future these customers may take their business elsewhere.) Or it may be able to get by with lower inventories of mattresses. (The cost is that it may lose business if there is a rush of orders that it cannot supply.)

Short-term financing plans are developed by trial and error. You lay out one plan, think about it, and then try again with different assumptions on financing and investment alternatives. You continue until you can think of no further improvements.

Trial and error is important because it helps you understand the real nature of the problem the firm faces. Here we can draw a useful analogy between the process of planning and Chapter 10, “A Project Is Not a Black Box.” In Chapter 10 we described sensitivity analysis and other tools used by firms to find out what makes capital investment projects tick and what can go wrong with them. Dynamic’s financial manager faces the same kind of task: not just to choose a plan but to understand what can go wrong with it and what will be done if conditions change unexpectedly.12

A Note on Short-Term Financial Planning Models

Working out a consistent short-term plan requires burdensome calculations.13 Fortunately much of the arithmetic can be delegated to a computer. Many large firms have built short-term financial planning models to do this. Smaller companies like Dynamic Mattress do not face so much detail and complexity and find it easier to work with a spreadsheet program on a personal computer. In either case the financial manager specifies forecasted cash requirements or surpluses, interest rates, credit limits, etc., and the model grinds out a plan like the one shown in Table 30.9. The computer also produces balance sheets, income statements, and whatever special reports the financial manager may require.

Smaller firms that do not want custom-built models can rent general-purpose models offered by banks, accounting firms, management consultants, or specialized computer software firms.

12This point is even more important in long-term financial planning. See Chapter 29.

13If you doubt that, look again at Table 30.9. Notice that the cash requirements in each quarter depend on borrowing in the previous quarter, because borrowing creates an obligation to pay interest. Also, borrowing under a line of credit may require additional cash to meet compensating balance requirements; if so, that means still more borrowing and still higher interest charges in the next quarter. Moreover, the problem’s complexity would have been tripled had we not simplified by forecasting per quarter rather than by month.

866 |

PART IX Financial Planning and Short-Term Management |

Most of these models are simulation programs.14 They simply work out the consequences of the assumptions and policies specified by the financial manager. Optimization models for short-term financial planning are also available. These models are usually linear programming models. They search for the best plan from a range of alternative policies identified by the financial manager.

As a matter of fact, we used a linear programming model developed by Pogue and Bussard15 to generate Dynamic Mattress’s financial plans. Of course, in that simple example we hardly needed a linear programming model to identify the best strategy. It was obvious that Dynamic should always use the line of credit first, turning to the second-best alternative (stretching payables) only when the limit on the line of credit was reached. The Pogue–Bussard model nevertheless did the arithmetic quickly and easily.

Optimization helps when the firm faces complex problems with many interdependent alternatives and restrictions for which trial and error might never identify the best combination of alternatives.

Of course the best plan for one set of assumptions may prove disastrous if the assumptions are wrong. Thus the financial manager has to explore the implications of alternative assumptions about future cash flows, interest rates, and so on. Linear programming can help identify good strategies, but even with an optimization model the financial plan is still sought by trial and error.

30.6 SOURCES OF SHORT-TERM BORROWING

Dynamic solved the greater part of its cash shortage by borrowing from a bank. But banks are not the only source of short-term loans. Finance companies are also a major source of cash, particularly for financing receivables and inventories.16 In addition to borrowing from an intermediary like a bank or finance company, firms also sell short-term commercial paper or medium-term notes directly to investors. It is time to look more closely at these sources of short-term funds.

Bank Loans

To finance its investment in current assets, a company may rely on a variety of short-term loans. Obviously, if you approach a bank for a loan, the bank’s lending officer is likely to ask searching questions about your firm’s financial position and its plans for the future. Also, the bank will want to monitor the firm’s subsequent progress. There is, however, a good side to this. Other investors know that banks

14Like the simulation models described in Section 10.2, except that the short-term planning models rarely include uncertainty explicitly. The models referred to here are built and used in the same way as the long-term financial planning models described in Section 29.4.

15G. A. Pogue and R. N. Bussard, “A Linear Programming Model for Short-Term Financial Planning under Uncertainty,” Sloan Management Review, 13 (Spring 1972), pp. 69–99.

16Finance companies are firms that specialize in lending to businesses or individuals. They include independent firms, such as Household Finance, as well as subsidiaries of nonfinancial corporations, such as General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC). In their lending finance companies compete with banks. However, they raise funds not by attracting deposits, as banks do, but by issuing commercial paper and other longer-term securities.

CHAPTER 30 Short-Term Financial Planning |

867 |

are hard to convince, and, therefore, when a company announces that it has arranged a large bank facility, the share price tends to rise.17

Bank loans come in a variety of flavors.18 Here are a few of the ways that they differ.

Commitment Companies sometimes wait until they need the money before they apply for a bank loan, but nearly three-quarters of commercial bank loans are made under commitment. In this case the company establishes a line of credit that allows it to borrow from the bank up to an established limit. This line of credit may be an evergreen credit with no fixed maturity, but more commonly it is a revolving credit (revolver) with a fixed maturity of up to three years.

Credit lines are relatively expensive, for in addition to paying interest on any borrowings the company must pay a commitment fee on the unused amount. In exchange for this extra cost, the firm receives a valuable option: It has guaranteed access to the bank’s money at a fixed spread over the general level of interest rates. This amounts to a put option, because the firm can sell its debt to the bank on fixed terms even if its own creditworthiness deteriorates or the cost of credit rises. The growth in the use of credit lines is changing the role of banks. They are no longer simply lenders; they are also in the business of providing companies with liquidity insurance.

Many companies discovered the value of this insurance in 1998, when Russia defaulted on its borrowings and created turmoil in the world’s debt markets. Companies in the United States suddenly found it much more expensive to issue their own debt to investors. Those who had arranged lines of credit with their banks rushed to take advantage of them. As a result, new debt issues languished, while bank lending boomed.19

Maturity Most bank loans are for only a few months. For example, a company may need a short-term bridge loan to finance the purchase of new equipment or the acquisition of another firm. In this case the loan serves as interim financing until the purchase is completed and long-term financing is arranged. Often a short-term loan may be needed to finance a temporary increase in inventory. Such a loan is described as self-liquidating; in other words, the sale of goods provides the cash to repay the loan.

Banks also provide longer-term loans, known as term loans. A term loan typically has a maturity of four to five years. Usually the loan is repaid in level amounts over this period, though there is sometimes a large final balloon payment or just a single bullet payment at maturity. Banks can accommodate the repayment pattern to the anticipated cash flows of the borrower. For example, the first repayment might be delayed a year until the new factory is completed. Term loans are often renegotiated before maturity. Banks are willing to do this if the

17See C. James, “Some Evidence on the Uniqueness of Bank Loans,” Journal of Financial Economics 19 (1987), pp. 217–235.

18The results of a survey of the terms of business lending by banks in the United States are published quarterly in the Federal Reserve Bulletin (see www.federalreserve.gov/releases/E2/).

19The rush to draw on bank lines of credit is described in M. R. Saidenberg and P. E. Strahan, “Are Banks Still Important for Financing Large Businesses?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Current Issues in Economics and Finance 5 (August 1999), pp. 1–6.

868 |

PART IX Financial Planning and Short-Term Management |

borrower is an established customer, remains creditworthy, and has a sound business reason for making the change.20

Rate of Interest Short-term bank loans are often made at a fixed rate of interest, which is often quoted as a discount. For example, if the interest rate on a one-year loan is stated as a discount of 5 percent, the borrower receives 100 5 $95 and undertakes to pay $100 at the end of the year. The return on such a loan is not 5 percent, but 5/95 .0526, or 5.26 percent.

For longer-term bank loans the interest rate is usually linked to the general level of interest rates. The most common benchmarks are the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), the federal funds rate,21 or the bank’s prime rate. Thus, if the rate is set at “1 percent over LIBOR,” the borrower may pay 5 percent in the first three months when LIBOR is 4 percent, 6 percent in the next three months when LIBOR is 5 percent, and so on.22

Syndicated Loans Some bank loans are far too large for a single bank. In these cases the loan may be arranged by one or more lead banks and then parceled out among a syndicate of banks. For example, when Vodafone Airtouch needed to borrow $24 billion (a25 billion) to help finance its bid for the German telephone company, Mannesmann, it engaged 11 banks from around the world to arrange a large syndicate of banks that would lend the cash.

Loan Sales Large banks often have more demand for loans than they can satisfy; for smaller banks it is the other way around. Banks with an excess demand for loans may solve the problem by selling a portion of their existing loans to other institutions. Loan sales have mushroomed in recent years. In 1991 they totalled only $8 million; by 2000 they had reached $129 billion.23

These loan sales generally take one of two forms: assignments or participations. In the former case a portion of the loan is transferred with the agreement of the borrower. In the second case the lead bank maintains its relationship with its borrowers but agrees to pay over to the buyer a portion of the cash flows that it receives.

Participations often involve a single loan, but sometimes they can be huge deals involving hundreds of loans. Because these deals change a collection of nonmarketable bank loans into marketable securities, they are known as securitizations. For example, in 1996 the British bank, Natwest, securitized about one-sixth of its loan book. Natwest first put together a $5 billion package of about 200 loans to major firms in 17 different countries. It then sold notes, each of which promised to pay a proportion of the cash that it received from the package of loans. Because the notes provided the chance to share in a diversified portfolio of high-quality loans, they proved very popular with investors from around the world.

Security If a bank is concerned about a firm’s credit risk, it will ask the firm to provide security for the loan. Since the bank is lending on a short-term basis, this

20Term loans typically allow the borrower to repay early, but in many cases the loan agreement specifies that the firm must pay a penalty for early repayment.

21The federal funds rate is the rate at which banks lend excess reserves to each other.

22In addition to paying interest, the borrower may be obliged to maintain a minimum interest-free deposit (compensating balance) with the bank. Compensating balances for bank loans are now relatively rare.

23Loan Pricing Corporation (www.loanpricing.com).