Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

700

Table 11.1. Tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging of bladder cancer

Primary tumor:

Tx |

Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 |

No evidence of primary tumor |

Ta |

Non-invasive papillary carcinoma |

Tis |

Carcinoma in situ |

T1 |

Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue |

T2a |

Tumor invades superficial muscle |

T2b |

Tumor invades deep muscle |

T3 |

Tumor invades perivesical tissue |

T4a |

Tumor invades prostate, uterus, vagina |

T4b |

Tumor invades pelvic wall, abdominal wall |

Lymph nodes: |

|

Nx |

Regional nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 |

No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 |

Metastasis to single lymph node 2 cm or less |

|

in greatest dimension |

N2 |

Metastasis to single lymph node larger than |

|

2 cm but not more than 3 cm |

N3 |

Metastasis in a lymph node more than 3 cm |

|

in greatest dimension |

Distant metastasis:

Mx Distant metastases cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis

M1 Distant metastasis

Tumor stages: |

|

|

|

Stage 0a |

Ta |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage 0is |

Tis |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage I |

T1 |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage II |

T2a |

N0 |

M0 |

|

T2b |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage III |

T3 |

N0 |

M0 |

|

T4a |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage IV |

T4b |

N0 |

M0 |

|

any T |

N1 |

M0 |

|

any T |

N2 |

M0 |

|

any T |

N3 |

M0 |

|

any T |

any N |

M1 |

Source: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition (2002), published by Springer-Verlag, New York, NY, used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, IL.

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

mucosa (22). In patients with a bladder cancer, the presence or absence of accompanying carcinoma in situ or epithelial dysplasia does not seem to influence survival significantly.

Recent cystoscopic biopsy leads to confusion because of edema and interferes with accurate tumor staging, and it is reasonable to delay a staging imaging study for several weeks after biopsy.

For superficial bladder tumors clinical staging (cystoscopy and biopsy) appears superior to MRI, but MRI is better than clinical staging for more infiltrating tumors.

Currently CT is not sufficiently accurate in staging bladder tumors ranging from carcinoma in situ through tumors invading deep muscle. Because no definite fat planes exist between bladder and adjacent posterior structures, CT cannot readily define the invasion of these structures (Figs. 11.8 and 11.9). Seminal vesicles have a CT soft tissue density whether invaded or not; an exception is the seminal vesicle anterior surfaces, where fat angle obliteration between the seminal vesicle anterior surface and posterior bladder wall implies tumor invasion. Computed tomography is more accurate with more advanced tumors. Computed tomography does evaluate for metastases. Overall CT staging accuracy is only 30% to 40% and CT changes management in only few patients.

system is used for both pretherapy staging and postresection staging (pathologic staging). Tumor stage is the most important predictive prognosis factor. The presence of bilateral ureteral obstruction affects the prognosis. Over 90% of patients with bilateral obstruction have extravesical extension of their cancer, but among those with unilateral obstruction a third have disease confined to the bladder, at times with the cancer even limited to the bladder

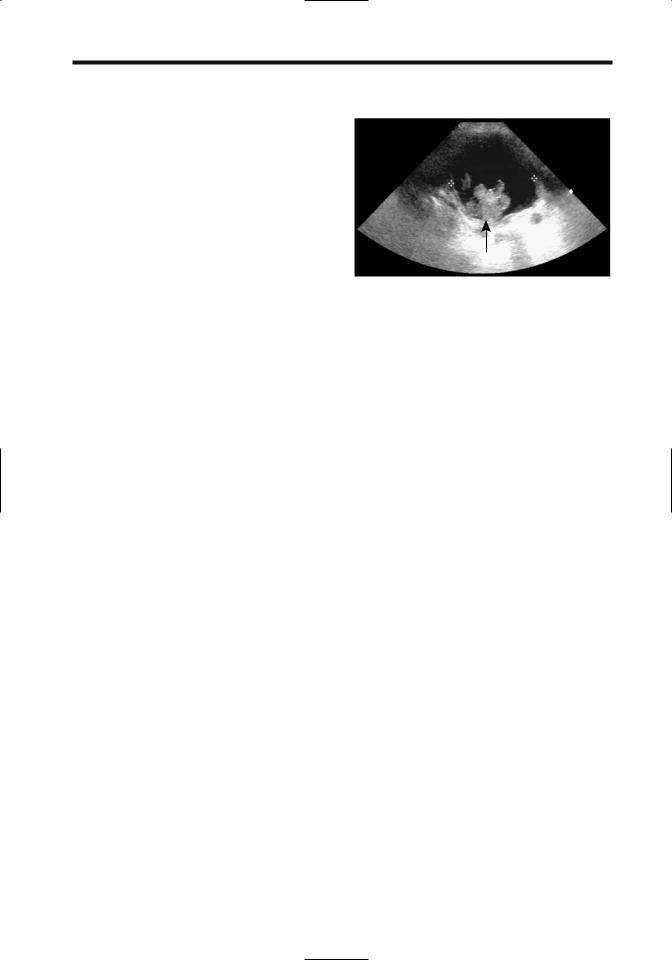

Figure 11.8. Invasive bladder carcinoma. Computed tomography identifies an infiltrating tumor in the left posterior bladder wall. It was inseparable from the uterus and sigmoid colon but invasion could not be determined. (Courtesy of Patrick Fultz, M.D., University of Rochester.)

701

BLADDER

Transabdominal US is seldom used to stage bladder cancers, having been replaced by more accurate imaging modalities. Endorectal US also has a low accuracy, but endourethral US shows promise in local staging of these tumors, especially for those limited to the bladder wall. Endourethral US is useful in detecting tumors in bladder diverticula.

Although color Doppler US detects some vascularity in transitional cell carcinomas, the Doppler findings are not helpful in evaluating tumor grade or stage, although in general, larger and higher-grade tumors tend to be more vascular.

Magnetic resonance imaging has the potential for accurate bladder tumor staging, although both CT and MR tend to overstage more often than understage. The use of surface coils leads to better image quality than does the use of body coils. Endorectal coils improve visualization of the bladder base and dorsal structures but are of limited use for the rest of the bladder. T1-weighted images provide good contrast between hyperintense perivesical fat and isointense bladder wall, and detects perivesical fat invasion, spread to lymph nodes, and bone marrow metastases; the latter are identified against the hyperintense normal marrow. T2weighted images evaluate bladder wall infiltration and prostatic and adjacent structure invasion, although differentiation between tumor and edema is difficult. Using early-phase contrast enhancement, MRI achieves relatively

high staging accuracy, especially in differentiating between superficial tumors and those invading muscle. Magnetic resonance appears especially useful in evaluating depth of bladder wall invasion. It thus appears reasonable to perform MRI before resection. Postcontrast MR reveals early tumor enhancement and appears more sensitive and specific than precontrast imaging. Bladder cancers begin to enhance several seconds after the start of arterial enhancement, which is earlier than most other structures.

When staging for lymph node involvement, CT and conventional MRI appear comparable. The accuracy of MRI is very technique dependent, and the results obtained with a specific technique do not apply to all MR scanners and techniques. Lymph nodes have longer T1 relaxation times than fat and thus T1-weighted images are useful in distinguishing nodes from adjacent pelvic fat, although subtle findings are better defined with postcontrast fat-suppressed images. Separating adjacent skeletal muscle from nodes, on the other hand, is easier on T2weighted images, and thus several sequences are usually employed. In either case, CT and MRI simply detect whether a lymph node is enlarged or not but cannot detect whether it is infiltrated by tumor or enlarged secondary to a benign cause.

Bladder cancers spread to the lungs; chest radiography is a simple screening test, at times supplemented by chest CT. Bone scintigraphy is

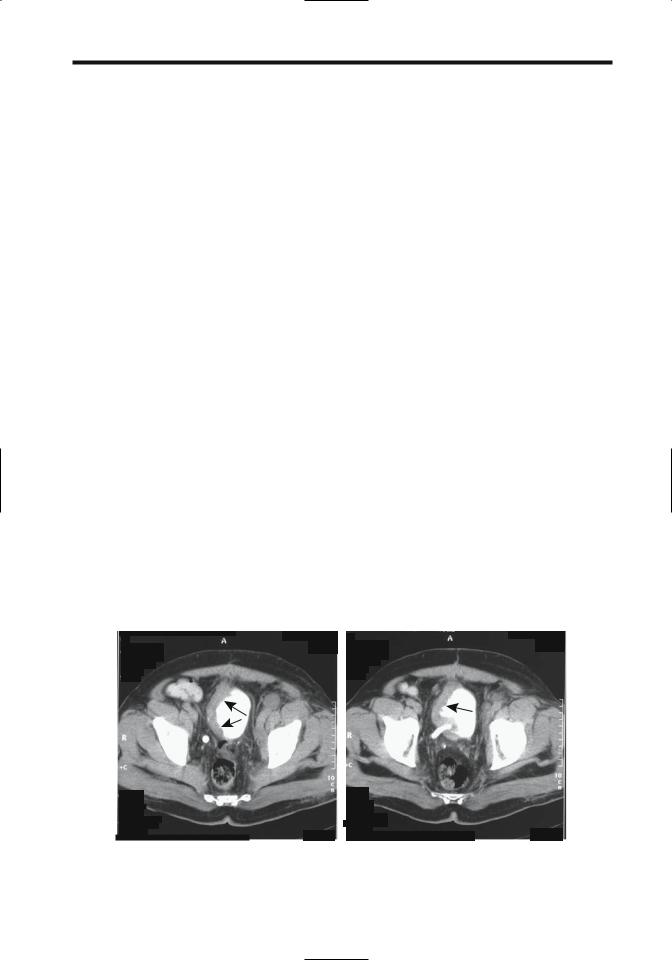

A |

B |

Figure 11.9. Invasive bladder carcinoma. More superior (A) and inferior (B) transverse pelvic CT images show marked right-sided bladder wall thickening (arrows). Reflux into the right ureter is evident. The cancer is extending almost to the anterior abdominal wall. (Courtesy of Egle Jonaitiene, M.D., Kaunas Medical University, Kaunas, Lithuania.)

702

not commonly obtained at initial staging unless symptoms suggest bone metastases.

Attempts have been made to evaluate bladder cancers with positron emission tomography (PET) using both 2-[18F]-fluoro-deoxy-D- glucose (FDG) and other compounds, but the results for local tumor spread are not superior to those of more traditional imaging. Urinary excretion of FDG limits tumor identification from the surrounding activity. For detecting lymph node involvement, however, PET-FDG in patients with bladder neck carcinoma achieved a 67% sensitivity and 86% specificity (23); these results appear superior to those obtained with CT or MRI studies.

Therapy

Therapy of a bleeding, nonresectable bladder cancer is difficult. One approach is intraarterial chemoperfusion with mitoxantrone, which in one study controlled hemorrhage in 14 of 15 patients (24). In patients with life-threatening bleeding, intraarterial embolization is the procedure of choice.

Resection: Resection ranges from local excision, to segmental resection, to radical cystectomy. The surgical therapy adopted depends on the extent of tumor and varies for superficial disease and muscle-invasive disease. Noninvasive, low-grade cancers are often fulgurated. The 5-year survival for patients with treated bladder carcinoma-in-situ is about 90%. Stage Ta and some T1 cancers are resected transurethrally. Nevertheless, because of a high rate of recurrence even with these tumors, additional therapy is often instituted; surveillance cystoscopy results in an excellent 5-year survival. Dysplasia or a multicentric cancer requires resection. T1 disease, by definition, signifies lamina propria invasion but is still considered superficial; if treated by focal resection, recurrence eventually develops in almost half of these patients and the surgeon is faced with a dilemma in these patients between focal resection and a cystectomy.

In the United States, therapy for stage T2 to T4 bladder cancer is generally a total cystoprostatectomy. Two types of ileal conduits are constructed after bladder resection: a stomal noncontinent ileal diversion or a continent urinary reservoir anastomosed to either the urethra or a cutaneous stoma requiring inter-

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

mittent catheterization (Kock pouch). The ureters are anastomosed to the neobladder. In some countries radiotherapy is preferred initially. Some stage pT2 bladder transitional cell carcinomas are treated by conservative surgery and iridium-192 brachytherapy.

Urinary tract diversion into the sigmoid colon was the initial anastomosis performed after a cystectomy until this operation was superseded by the use of various ileal conduits. A ureterosigmoidostomy is still encountered in the follow-up of previously operated patients. The complications of such diversion includes septic reflux, anastomotic stenosis, and hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis.

A study of patients undergoing cystectomy for bladder cancer found the 5-year survival for those with tumors confined to the bladder (<T3) to be 79%, but in patients with tumor spread beyond the bladder (>T3) survival was only 28% (25); from a lymph node viewpoint, 5-year survival for those with N0, N1, and N2–3 nodes was 64%, 48% and 14%, respectively.

Cystectomy is generally not considered for tumors extending beyond the bladder wall. Prostatic involvement is common with invasive transitional cell bladder cancers. Transitional cell carcinoma has a tendency to invade the prostatic urethra, and such invasion has a poor prognosis. Also, intravesical chemotherapy is ineffective in the prostatic urethra.

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin: Besides surgery, chemotherapy and immunotherapy with BCG are used to treat superficial bladder cancer. After the initial resection of a superficial transitional cell carcinoma, the risk of a subsequent tumor is decreased by adding either intravesical adjuvant chemotherapy or BCG immunotherapy. Some long-term studies of intravesical chemotherapy, however, reveal a limited decrease in tumor recurrence, and the use of routine prophylactic intravesical chemotherapy is questioned. BCG, on the other hand, is an effective intravesical agent in the prophylaxis and therapy of superficial transitional cell carcinoma; nevertheless, the use of BCG for Ta and T1 cancers varies considerably.

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin is a potent immune stimulant and exerts a direct toxic effect. Intravesical instillation leads to an inflammatory and immune cell infiltration into bladder lamina propria. The use of BCG prophylaxis results in less tumor recurrence than with surgical tumor

703

BLADDER

resection. Therapy with BCG in patients with primary bladder carcinoma-in-situ leads to complete response in a majority of patients. It appears to delay progression and the need for cystectomy in high-risk patients—those with dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and multiple primary tumors. Low-dose BCG therapy in high-risk patients with stage T1, grade 3 bladder tumors combined with transurethral tumor resection resulted in 80% of patients responding to BCG instillation (26).

Among patients with pTa or pT1 bladder tumors treated by transurethral resection and intravesical BCG with 2 years of maintenance therapy, 62% of patients were recurrence-free at 48 months (27); a similar group of patients treated by transurethral resection alone and a group treated with transurethral resection and mitomycin C achieved recurrence-free results in 18% and 38% of patients, respectively. At 42 months, 11% of pT1 tumors treated with BCG had progressed to invasive carcinoma, compared to 25% of those treated by transurethral resection alone and 21% of those treated with transurethral resection and mitomycin C (27).

In a minority of patients BCG instillation results in toxicity, and a number of complications develop. In addition to the sequelae of tuberculous infection, tuberculous lymphadenitis leads to tumor overstaging. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy for superficial bladder tumor led to epididymitis and epididymal abscess requiring an orchidectomy (28). Tuberculous enteritis (29) and mycotic aneurysms (30) have developed. In France, BCG Pasteur strain was used previously, more recently being supplanted by the Connaught (Toronto) strain. Toxicity appears similar for the two strains (31).

Ultrasonography after BCG therapy reveals hypoechoic foci in the prostate transition zone, representing necrotizing granulomas; confusing the issue is that bladder carcinoma invading the prostate also appears hypoechoic, and thus biopsies of these lesions are indicated.

Other Therapy: Some advanced bladder cancers are treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Computed tomographic cystography commonly identifies bladder wall thickening at a tumor site after radiotherapy and chemotherapy due to a granulomatous reaction even without tumor recurrence. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) appears useful in

evaluating the chemotherapy response in patients with advanced bladder cancer. Using persisting early contrast enhancement as a criterion, MRA achieves high sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing responders from nonresponders.

Superficial bladder tumors have been treated cystoscopically by injecting ethanol through a needle into the tumor base. Photodynamic therapy for small papillary bladder cancers achieves a response.

Interferon-a appears useful in carcinoma in situ and primary and recurrent papillary transitional cell carcinomas, although the response and relapse rates are inferior to those of BCG. Intravesical recombinant interferon-a therapy also appears useful in patients not responding or refractory to BCG therapy. Interleukin-2 is a potential agent in bladder cancer therapy. Even garlic appears to inhibit cancer cell growth and protects against suppression of immunity by chemotherapy (32).

Microwave-induced hyperthermia is occasionally mentioned for recurrent superficial bladder tumors not amenable to transurethral resection.

Metastasis/Recurrence

Clinical: After resection of one tumor, whether a new bladder tumor represents a recurrence or a new metachronous tumor is often unclear. Findings of distinct foci of synchronous carcinoma or carcinoma in situ argue for separate tumors. On the other hand, the increased risk for subsequent bladder cancers after an upper tract transitional cell carcinoma and lower risk of upper tract tumors after an initial bladder cancers argues for tumor dissemination.

Most recurrence of bladder carcinoma is detected within several years of initial surgery, with risk gradually tapering thereafter, although occasional metastases are detected a decade or longer after cystectomy. Most bladder cancers spread locally. Urethral recurrence after cystoprostatectomy occurs in about 5% of patients. Following cystectomy, recurrence within an ileal conduit is uncommon. Some tumors recur in regional lymph nodes, and distant metastases eventually develop in up to one third. Distal metastases are most common to the lungs, and then to the lymph nodes, bone, and liver. Rarer sites include malignant pericardial

704

effusion and brain metastases. The gastrointestinal tract is rarely involved, with an occasional recurrence presenting as an annular rectal tumor. An uncommon cancer spreads intraperitoneally and results in ascites and peritoneal carcinomatosis. If possible, a site of tumor origin should be determined because transitional cell bladder carcinomas have a worse prognosis than similar spread from the ovaries.

Surveillance: Cystoscopy and urine cytology are traditional surveillance examinations in the follow-up of bladder cancer; keep in mind that although urine cytology sensitivity is only about 30% to 50%, its specificity approaches 100%. Several other tests, including bladder tumor antigen, fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products, and nuclear matrix protein tests, are in use to a varying degree in different countries. The published evidence suggests that some of them even surpass cytology in detecting recurrence, but their role in routine follow-up is not clearly established and they are often employed as ancillary tests.

The postoperative imaging approach varies depending on the type of resection (if any). For most superficial bladder cancers no imaging follow-up is necessary unless additional risk factors are present: tumor >3cm, several tumor foci, higher than grade I tumor, or the presence of additional foci of dysplasia.

Follow-up imaging of invasive transitional cell carcinomas consists of CT, chest radiography, IV urography, and, in some centers, US. The role of MRI is still evolving. Computed tomography is recommended every 3 to 6 months initially. Because therapy causes considerable distortion, an initial posttherapy CT study is especially valuable to establish a baseline. Posttherapy edema, fibrosis, and tumor recurrence have a similar CT appearance. Edema is identified as a diffuse increase in perivesical fat density. One recommendation after successful bladder cancer therapy is that these patients be followed with an IV urogram or similar imaging study to assess for upper urinary tract cancer, on the average every 1 to 2 years, although some believe that subsequent studies should be tailored to the clinical findings.

The evidence is accumulating that MRI is more accurate than CT in detecting bladder cancer recurrences, and a gradual shift toward MR studies is evident. No firm guidelines

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

are established. T2-weighted images are useful in differentiating late recurrence (isoto hyperintense) from residual fibrosis (hypointense). Within 6 to 12 months after therapy, however, these differences cannot be reliably differentiated.

The use of US for postoperative surveillance of bladder cancers is occasionally suggested, but a low sensitivity limits its use.

Adenocarcinoma

Bladder adenocarcinomas are not common. Many are primarily urachal in origin, involve the bladder dome, and are not of direct bladder origin, but a bladder carcinoma is in the differential diagnosis. An occasional bladder adenocarcinoma is associated with long-standing irritation and has developed in a defunctionalized bladder. A rare bladder adenocarcinoma is a consequence of bladder endometriosis.

A signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma or linitis plastica of the bladder is a highly malignant tumor having a poor prognosis. Most of these tumors contain signet-ring cells mixed with gland and papillary structures, at times even foci of transitional cell carcinoma. Compounding the issue is that a gastrointestinal or prostatic metastasis is often in the differential diagnosis, and thus a search for another primary is often necessary. A typical imaging appearance of a signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma is diffuse bladder wall invasion without a significant intraluminal component.

A hepatoid adenocarcinoma, representing extrahepatic hepatocellular differentiation, is a rare variant in the bladder; some of these tumors produce a-fetoprotein.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

In most countries bladder squamous cell carcinomas represents only several percent of all primary bladder cancers, but in schistosomia- sis-endemic countries a squamous cell carcinoma is the most common primary bladder cancer. In North America and Europe a squamous cell carcinoma is more common in bladder diverticula and is often associated with chronic bladder inflammation, such as longstanding bladder calculi or the presence of indwelling catheters.

705

BLADDER

A verrucoid carcinoma is a descriptive term for a squamous cell carcinoma having a frondlike pattern.

Computed tomography of primary squamous cell carcinoma often shows a predominantly extraluminal tumor component with invasion into adjacent structures, although some are predominantly intraluminal.

Lymphoma

Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the bladder is rare. Hematuria is the most common presentation, although prostatic involvement results in outlet obstruction. An occasional primary bladder lymphoma presents as a large pelvic tumor. Diffuse lymphomatous involvement simply thickens the bladder wall.

Magnetic resonance signal intensities from lymphoma-involved bladder are similar to those from adjacent lymphomatous lymph nodes.

An enterovesical fistula secondary to a nonHodgkin’s lymphoma is a rare complication.

Sarcoma

In adults, nonepithelial bladder malignancies include leiomyosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma; both are rare. These are aggressive, rapidly growing tumors with early local invasion. Rhabdomyosarcomas occur in both the bladder and the prostate. A biopsy should establish the diagnosis.

Imaging features for most sarcomas overlap. Extensive cystitis, lymphoma, and other tumors have a similar appearance. Ultrasonography reveals a large heterogeneous tumor. Doppler US typically detects nonpulsatile low velocity flow.

Sarcoma botryoides is a rhabdomyosarcoma originating in hollow organs and growing primarily intraluminally in grape-like clusters. A rare one arises from the bladder wall (Fig. 11.10).

Most bladder tumors in younger children are rhabdomyosarcomas. They are more common in boys. They tend to occur at the trigone or posterior bladder wall and either infiltrate or grow intraluminally as a lobular, irregular bladder tumor. Superficially, an intraluminal tumor tends to mimic blood clots. Some of these tumors prolapse into the urethra and obstruct. Those originating at the bladder dome can grow

Figure 11.10. Bladder rhabdomyosarcoma in a teenage boy with hematuria. US reveals a polypoid intraluminal tumor (arrow). (Courtesy of Luann Teschmacher, M.D., University of Rochester.)

intraabdominally; determining the site of origin for some of these is difficult.

The rare bladder malignant histiocytoma and histiocytofibroma are aggressive sarcomas, at times associated with a hematologic malignancy.

Carcinosarcoma and

Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

Some bladder carcinomas contain a prominent spindle cell component and are known as sarcomatoid carcinomas. Whether these are distinct from carcinosarcomas is debated in the pathologic literature (purists argue for distinct tumors). Other terms for these tumors are malignant mixed mesodermal tumor and metaplastic carcinoma. Whether this neoplasm is secondary to collision of two tumors or whether it represents separate differentiation from a single source is speculation.

The clinical presentation is similar to that of the more typical transitional cell carcinoma.

Among 15 patients with bladder carcinosarcoma seen at the Mayo Clinic, the most common carcinomatous component was a urothelial carcinoma, less often squamous cell carcinoma or small cell carcinoma, while the sarcomatous component consisted of chondrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and other types (33); during the same time frame 26 patients were diagnosed with a sarcomatoid carcinoma, with the tumor consisting primarily of an urothelial carcinoma.

706

A rare sarcomatoid carcinoma originates in a bladder diverticulum.

Both carcinosarcoma and sarcomatoid carcinoma are highly aggressive tumors having a similar outcome regardless of histologic findings and treatment. These tumors metastasize readily and mimic other neoplasms, including lymphoma. They have no characteristic imaging findings. Most are large, solid, exophytic tumors when first detected. Some bladder carcinosarcomas contain calcifications and even osseous metaplasia. The diagnosis is suggested by immunohistochemistry.

Metastases/Invasion

Invasion from an adjacent cancer is more common than metastasis to the bladder. Thus prostatic carcinoma, gynecologic malignancies, rectal and even an appendiceal carcinoma readily invade the bladder. Some of these extrinsic tumors mimic a primary bladder carcinoma.

Coincident upper tract transitional cell carcinomas and bladder cancers have already been discussed. An occasional upper tract cancer, however, metastasizes to the bladder and is not a second primary, although differentiation of these is difficult. An occasional renal cell carcinoma metastasis to the ureteral stump and bladder is detected after a nephrectomy.

Only a few metastatic melanomas to the bladder have been reported.

Local invasion is from the outer wall inward; thus cystoscopy will not detect early invasion. Computed tomography and MR evidence of an asymmetric bladder wall thickening and increased MR signal intensity of the involved bladder wall segment are signs of invasion. Eventual intraluminal extension is evident.

Small Cell Carcinoma

The rare bladder small cell carcinoma appears to be less aggressive than a similar lung carcinoma. One should keep in mind that neuroendocrine tumors also have a small cell appearance but are characterized by their immunohistochemical properties; in some publications a distinction between small cell carcinomas and some neuroendocrine tumors is blurred. Histologically, these tumors also tend

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

to mimic lymphoma. Occasionally bladder metastases from lung cancer has a similar appearance. Imaging simply reveals a solid tumor.

Most of these tumors result in hematuria. Adding chemotherapy to radical surgery appears to improve survival.

Neuroendocrine Tumors

The bladder trigone contains cells of neural crest origin.

Neurofibroma

The most common genitourinary involvement by neurofibromatosis is in the bladder.Although an occasional single neurofibroma is detected, more often these tumors are part of neurofibromatosis type I. Only a rare bladder neurofibroma is malignant. A trigone neurofibroma can obstruct an adjacent ureter.

These tumors range from a focal, wellmarginated one to diffuse infiltration by a plexiform neurofibroma. Some neurofibromas have an imaging appearance similar to that of bladder leiomyomas, although neurofibromas often are more hyperintense on T2-weighted images than leiomyomas.

Paraganglioma (Pheochromocytoma)

Paragangliomas are uncommon catecholamineproducing tumors originating from chromaffin cells in the bladder paraganglion system. They can be multicentric. The most common location is in the trigone, followed by the bladder dome. Only an occasional one is malignant.

Hematuria is common. Some patients develop atypical hypertension, including palpitations, excessive sweating, paroxysmal hypertension, or even a hypertensive crisis during micturition due to release of epinephrine or norepinephrine.

Similar to other sites, bladder paragangliomas are solid, hypervascular tumors readily detected by CT and angiography. At times selective venous blood sampling is helpful in localizing these tumors. An occasional paraganglioma contains curvilinear calcification. Ultrasonography shows a solid, echogenic mass containing low-impedance flow. These tumors are interme-

707

BLADDER

diate to hypointense on T1and hyperintense on T2-weighted MR images.

Long-term follow-up is necessary after resection of these tumors because recurrences or metastases can develop years later.

Intraluminal Mass

Causes of intraluminal bladder masses not attached to the bladder wall include blood clots, stones, fungus balls, and foreign bodies/ bezoars.

Bladder calculi either form in the kidney and migrate to the bladder, or form de novo in the bladder. In certain parts of Asia and Africa bladder stones develop in children, called endemic bladder stones. Primary bladder calculi develop in a setting of stasis or the presence of a foreign body. Most small stones are mobile, with an occasional one adhering to the bladder wall due to adjacent inflammation. Thickening of the bladder wall is common. Stasis in an hourglass bladder incarcerated within a hernia has led to stone formation.

Occasionally giant bladder calculi fill almost the entire bladder lumen. Most of these stones contain calcium and are relatively radiopaque.

Bladder and urethral stones can be treated by ultrasonic lithotripsy, using either a transurethral or a percutaneous cystolithotripsy approach.

The most common entry site for bladder foreign bodies is through the urethra, with the foreign body being either self-introduced or introduced during a transurethral surgical procedure. Items mentioned in the literature range from bizarre household products to various surgical instruments. A second access route is during laparotomy or laparoscopic procedures. Least common are foreign bodies migrating from a site outside the bladder; these include such foreign bodies as synthetic gum used to protect a surgical ureterostomy and an intrauterine device migrating into the bladder lumen. Shotgun pellets have been passed spontaneously during voiding.

Clinical presentations range from recurrent infections to acute obstruction, depending on the type and location of a foreign body.

Dilation/Obstruction

Bladder outlet and urethral obstruction is discussed in Chapters 12 and 13.

Prolonged bladder outlet obstruction does lead to renal failure. An overdistended bladder resulted in bilateral iliac vein obstruction and bilateral urinary obstruction, and led to a pulmonary embolus (34).

Occasionally a patient with urinary retention has no anatomic obstruction, but “functional” bladder neck obstruction is believed to be responsible. Some of these patients with functional obstruction have normal cystourethrography and retrograde urethrography. The external sphincter opens during voiding but the bladder neck relaxes either intermittently or inadequately.

Neurogenic Bladder

Normal bladder intraluminal pressure is less than 10 to 15cm of water. In general, a chronic constant pressure of greater than about 40cm of water leads to bladder wall thickening, trabeculations, and outpouchings.

Bladder dysfunction is classified into an uninhibited neurogenic bladder, hyperreflexive detrusor (reflex neurogenic, contractile bladder), areflexic detrusor (autonomous neurogenic, flaccid bladder), and sensory or motor paralysis (Table 11.2).

In an uninhibited neurogenic bladder voluntary external sphincter contraction prevents voiding during uninhibited voiding. As a result, the posterior urethra is dilated to the external sphincter level and the imaging appearance is similar to a spinning top. These findings occur in infants with an immature bladder and adults with a cerebral cortical lesion (stroke, brain tumor). In infants the imaging appearance tends to be similar to that seen with posterior urethral valves.

Patients with a lesion above the lower lumbar level have detrusor hyperreflexia and develop a trabeculated thick-walled bladder. Such a hyperreflexive detrusor is found in patients with multiple sclerosis and lesions inducing spinal cord damage (trauma, tumor, syringomyelia). A large postvoid residue is common.

708

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Table 11.2. Summary of neurogenic bladder dysfunction

|

|

|

|

|

Uninhibited |

External |

|

|

Bladder |

Initiate |

Inhibit |

Bladder |

bladder |

sphincter |

Bladder |

Type |

sensation |

voiding |

voiding |

capacity |

contraction |

dyssynergia |

contour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Uninhibited |

+ |

+ |

- |

Ø |

+ |

± |

Smooth or |

neurogenic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

trabeculated |

Reflex neurogenic |

- |

- |

- |

Ø |

+ |

+ |

Trabeculated |

Autonomous |

- |

- |

- |

≠ |

- |

+ |

Smooth or |

neurogenic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

trabeculated |

Sensory paralytic |

- |

+ |

+ |

≠≠ |

- |

- |

Smooth |

Motor paralytic |

+ |

- |

- |

≠ |

- |

± |

Smooth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bladder contractions result in bladder neck opening, but the striated external sphincter does not open and thus bladder pressure increases. Associated vesicoureteral reflux is common in these patients, and if not corrected often results in loss of renal function.

Lower motor neuron involvement leads to detrusor areflexia. These patients develop a large, thin-walled bladder. No detrusor contractions are evident with an areflexic detrusor. The bladder neck remains open, external sphincter does not constrict normally, and these patients are incontinent.

Additional variants of a neurogenic bladder include sensory and motor paralysis. The former is most often found in diabetics. An association exists between gastroparesis and bladder dysfunction; patients with both idiopathic gastroparesis and diabetic gastroparesis are affected. Presumably a similar autonomic neuropathy is responsible for both gastric and bladder involvement.

Motor paralysis develops in some multiple sclerosis and polio patients. Urinary incontinence and retention are common problems in multiple sclerosis, often presenting a complex appearance. A majority of multiple sclerosis patients have detrusor hyperreflexia and a minority areflexia; these patients also develop bladder diverticula, urinary infection, hydronephrosis, and reflux.

Voiding dysfunction develops in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Dysfunction improves in some after a decompressive laminectomy, but others continue with a poor outcome.

A neurogenic bladder has been reported in Wolfram’s syndrome (diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness) (35).

Autonomic dysreflexia, encountered in patients with a neurogenic bladder and similar conditions, is discussed later (see Examination Complications).

Calcifications

Bladder lumen calcifications consist of calculi and foreign bodies. Bladder wall calcifications include infections (schistosomiasis and tuberculosis), neoplasms, therapy related (radiation, chemo-, and immunotherapy, cyclophosphamide, BCG, thiotepa, and mitomycin C), phleboliths, arteriosclerosis, alkaline cystitis, and amyloidosis. Some calcifications are readily apparent with conventional radiography while others are detected only with a higher radiographic contrast imaging modality such as CT.

Fistula

Vesicovaginal

Common causes of vesicovaginal fistulas are prior gynecologic procedure, such as hysterectomy, and, in rural North Africa, obstetrical trauma (36). Less common etiologies include adjacent neoplasms and radiation therapy.

Cystography is the procedure of choice to detect these fistulas. A vaginogram is less often

709

BLADDER

diagnostic. In distinction to enterovesical fistulas, the presence of gas within the bladder is uncommon with a vesicovaginal fistula.

mal delivery (38). Not all manifest with vaginal urinary leakage; an occasional one results in hematuria.

Enterovesical

The most common cause of enterovesical fistulas in adults is sigmoid diverticulitis. Less often encountered are colon and bladder malignancies, Crohn’s disease, pelvic radiation, trauma, and infection by actinomycosis, tuberculosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, or an adjacent abscess, such as neglected appendicitis.

Indirect signs of a fistula include gas within the bladder and an irregular outline to the bladder wall. With some fistulas cystoscopy is noncontributory.

A suspected fistula is studied by cystography or barium enema; either study demonstrates most fistulas, although occasionally only one or the other outlines a fistula. A rare clinically suspected fistula is not detected with imaging; some of these become evident a week or so later. As a last resort, the Bourne test should be considered; following a nondiagnostic barium enema, a horizontal x-ray beam radiograph is obtained of a centrifuged urine sample. The sample may contain sufficient barium to be visible on the radiograph. The need for a Bourne test is rare and it is now mostly of historical interest.

Computed tomography and MRI outline some bladder fistulas. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR images are superior in showing a fistula compared to precontrast images. If a fistula is accessible, contrast injection into the fistula and fistulography or MRI should define it.

Occasionally Tc-99m–diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) renography shows radioactivity in the sigmoid colon with an enterovesical fistula.

Uterovesical

These fistulas are rare. In a collection of five uterovesical fistulas all were secondary to a prior cesarean section and all presented with intermittent hematuria (37); hysterosalpingography revealed some of these fistulas. In another collection of 10 such fistulas, 60% were secondary to cesarian section and 40% to prior abnor-

Diverticula

Bladder diverticula form when mucosa herniates through overlying muscle. A purist would thus describe them as pseudodiverticula, a term not generally used. Some diverticula have smooth muscle fibers within the wall. Fibrosis develops in some secondary to chronic inflammation. Diverticula may be single or multiple, small or large. Most diverticula have a wide neck. At times a diverticulum is larger than the remainder of the bladder. Very large diverticula tend to have a relatively smooth outline.

Diverticula may be primary developmental in origin or acquired secondary to another abnormality. An increased prevalence occurs in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and prune belly syndrome. They develop because of outflow obstruction, stasis, or prior surgery. An occasional one is associated with urinary retention or undergoes spontaneous rupture.

Diverticula close to the ureterovesical junction were described by Hutch in patients with a neuropathic bladder. These diverticula are believed to develop due to weakening of the detrusor muscle in this region and are associated with vesicoureteral reflux. If the ureter inserts into a diverticulum, the appearance mimics a ureterocele. Or, a Hutch diverticulum simply obstructs an adjacent ureter by its bulk.

A bladder diverticulum can be diagnosed by US if a communication with the main bladder lumen can be identified. Ultrasonography reveals an occasional bladder diverticulum as a complex pelvic tumor apparently separated from the bladder, leading to diagnostic confusion.

Endoscopic therapy of bladder diverticula has been performed with varying success.

The prevalence of neoplasms within a bladder diverticulum is greater than in a normal bladder, probably because of chronic inflammation and stasis. The most common neoplasm is a transitional cell carcinoma. Occasionally a sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or even an adenocarcinoma develops in a diverticulum.