Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

633

KIDNEYS AND URETERS

Multiple Myeloma

Renal histology in patients with myeloma nephropathy revealed 14% with tubulointerstitial nephritis, 11% with amyloidosis, 7% with acute tubular necrosis, and 4% each with nodular glomerulosclerosis and plasma cell infiltration (83); at times renal biopsy pro-vides the first clue to a diagnosis of myeloma by identifying myeloma cast nephropathy.

Tubular precipitation of Bence-Jones proteins |

|

|

is a cause of renal failure in multiple myeloma |

|

|

patients. Haphazard IV contrast injection is a |

|

|

cause of such precipitation, but with preplan- |

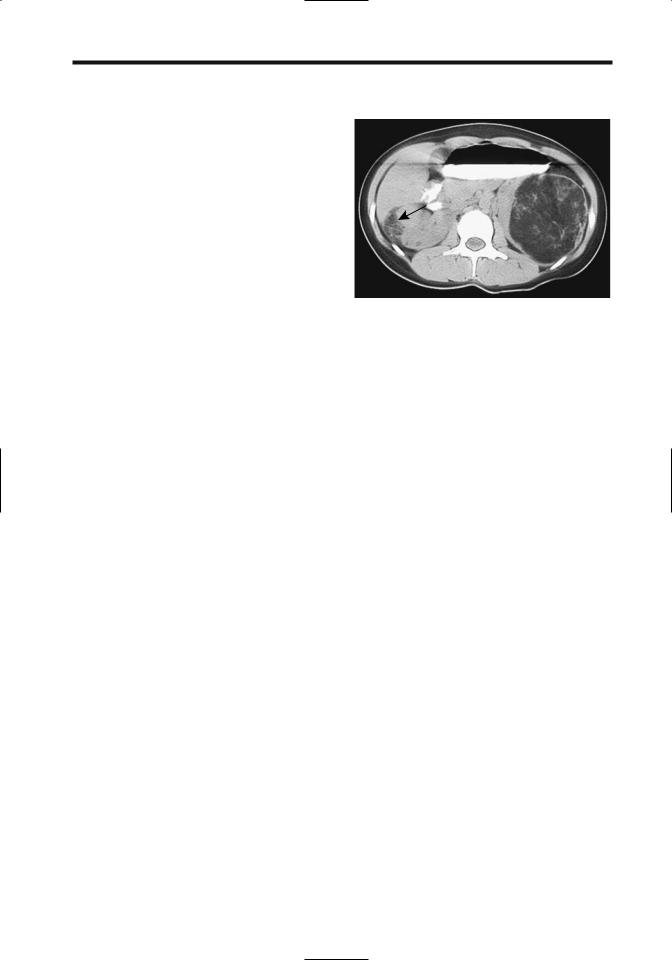

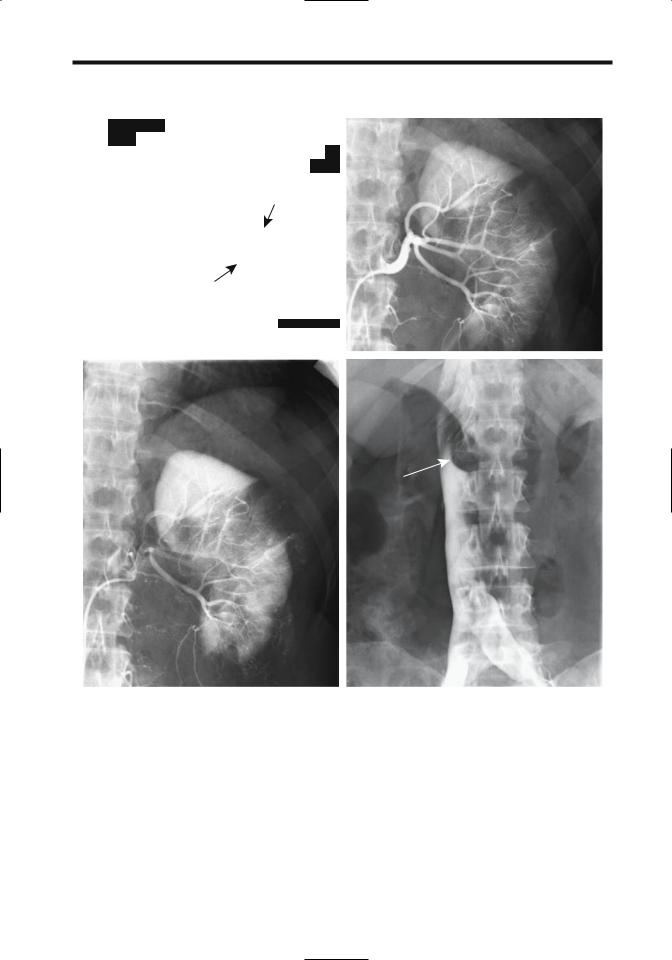

Figure 10.27. Renal angiomyolipomas in a 17-year-old with |

|

ning and adequate hydration a number of these |

||

tuberous sclerosis. The left fat-containing tumor is obvious. A |

||

patients have undergone contrast studies |

smaller angiomyolipoma is also present in the right kidney |

|

without complication. |

(arrow). (Courtesy of Luann Teschmacher, M.D., University of |

|

Resorption of calcium from bone and the |

Rochester.) |

|

resultant hypercalcemia lead to nephrocalci- |

|

|

nosis. The kidneys enlarge, and the collecting |

|

|

systems are compressed. These patients are also |

|

|

prone to developing uric acid calculi. |

oleiomyomatosis, and tumors at other sites, but |

|

Unexplained renal failure in a patient even |

in general extrarenal angiomyolipomas are rare. |

|

with absent skeletal lesions can still be due to |

These tumors develop in the renal capsule, |

|

multiple myeloma. |

cortex, and medulla. Histologically they are |

|

|

composed of haphazardly arranged blood |

|

Mesenchymal Neoplasms |

vessels, disorganized smooth muscle fibers, and |

|

Angiomyolipoma |

varying amounts of fat. Some contain sheets of |

|

epithelioid cells,suggesting a malignancy. Those |

||

Clinical |

without fat mimic a leiomyoma. Histologically, |

|

no sarcomatous transformation should be |

||

|

||

Classification of angiomyolipomas has evolved |

evident in either the leiomyomatous or |

|

from their being considered hamartomas to |

lipomatous components. |

|

benign neoplasms, although a rare one does |

Serial CT and US provide a measure of renal |

|

undergo sarcomatous transformation and a |

angiomyolipoma growth rates. The mean |

|

propensity to metastasize. Even the usually |

growth rate of isolated tumors is about 5% per |

|

benign variety tends to be locally aggressive and |

year, being considerably more in those with |

|

produces considerable mischief. In some studies |

tuberous sclerosis. No correlation exists |

|

20% to 50% are detected in tuberous sclerosis |

between the amount of fat in a tumor and its |

|

patients, where they tend to be multiple and |

growth rate. Growth tends to be unpredictable. |

|

bilateral. Angiomyolipomas are associated to a |

Some tumors are stable for years and then |

|

lesser degree with von Recklinghausen’s disease, |

undergo a fast increase in size, followed by |

|

von Hippel-Lindau disease, and adult polycystic |

another period of quiescence. Rapid growth |

|

disease, and are found in about half of patients |

occasionally occurs in pregnancy, suggesting |

|

with pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis. In |

that hormones play a role in their growth. An |

|

general, a finding of multiple angiomyolipomas |

occasional angiomyolipoma is huge at initial |

|

should suggest tuberous sclerosis (Fig. 10.27). |

presentation. |

|

In tuberous sclerosis, angiomyolipomas occur |

Spontaneous, solitary tumors are most |

|

earlier in life than sporadic ones, and most |

common in middle-aged women and are rare in |

|

are discovered incidentally. An occasional |

children. Pain, a palpable tumor, or hematuria is |

|

tuberous sclerosis patient develops bilateral |

a common presentation, although many of these |

|

renal angiomyolipomas,pulmonary lymphangi- |

tumors are asymptomatic. |

B

B B

B