Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

517

PANCREAS

makes acute pancreatitis worse; whether such data can be extrapolated to humans is unknown.

Currently a laparoscopic surgical approach is preferred but timing is controversial. Patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis can safely undergo an operation within the first week or so, but early surgery in severe biliary pancreatitis is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. On the other hand, a prolonged time interval between onset of biliary pancreatitis and subsequent surgery risks a recurrence of pancreatitis.

A prophylactic sphincterotomy can be performed as an alternative to cholecystectomy in patients with gallstone pancreatitis who are at increased surgical risk, such as with severe cardiopulmonary, hepatic, and renal disease. Sphincterotomy decreases the risk of a new episode of acute pancreatitis, although a cholecystectomy is eventually performed in most patients with gallstone-induced pancreatitis.

Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Necrotizing pancreatitis can be defined as necrosis of pancreatic glandular tissue, surrounding fat, interstitial tissue, and associated with regions of hemorrhage. Pancreatitis due to almost any etiology can evolve into pancreatic necrosis, although in many centers pancreatitis due to a biliary etiology predominates.

Infection of necrotic pancreatic tissue is generally considered an indication for surgical debridement. Infection is most often bacterial, especially coliform in origin, but an occasional fungal infection is encountered. Mortality in severe infected pancreatic necrosis is often due to multiorgan failure.

A fluid collection can be defined as not drainable if imaging identifies solid necrotic debris >1cm in diameter. In general, MRI appears to predict drainability better than CT or US.

Endoscopic drainage therapy is feasible in patients with extensive pancreatic necrosis. Resolution can be achieved nonoperatively in some patients by endoscopic drainage via stents and the placement of an intrapancreatic nasobiliary lavage catheter.

Another option is CTor US-guided percutaneous catheter drainage and transcatheter debridement of infected pancreatic necrosis as

the primary means of therapy. Debris is removed during multiple sessions using a combination of large-bore suction catheters, stone baskets, and large amounts of lavage fluid. Results of such drainage are mixed.

Surgeons continue to debate the merits of early versus delayed surgery in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Some studies suggest no difference in mortality rates between early and delayed surgery (33), but other find delayed necrosectomy superior.

Major hemorrhage is a complication after surgical management of pancreatic necrosis; most often such bleeding is controlled surgically, although in selected patients angiographic therapy is useful.

Prognosis

Several studies have found no differences in clinical course and outcome when patients with acute pancreatitis are subdivided by etiology into the categories (1) alcohol, (2) gallstones, and (3) other, except that pancreatic pseudocysts develop significantly more often in alcoholics than in patients with other etiologies. Another exception to the above is with ERCPinduced acute pancreatitis (see Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Induced, above). Tissue necrosis and pancreatic failure determine the mortality and morbidity of acute pancreatitis. The overall mortality rate in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis increases in those with infection (33).

A number of indexes have been developed to predict the severity and outcome of acute pancreatitis. Clinically, the severity of acute pancreatitis is evaluated using the Ranson prognostic factors, Glasgow, or Hong Kong criteria or the APACHE II score, while imaging relies on contrast-enhanced CT criteria or the Hill classification.

A consecutive series of patients with acute pancreatitis was used to predict the severity acute pancreatitis; the Hong Kong criteria achieved a sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 80%, the Ranson criteria values were 79% and 56%, and the Glasgow score was 83% and 60%, but the best prediction was provided by the APACHE II score (24 hours postadmission), with a sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 82% (34). While a correlation exists between clinical and imaging classifications at the two extremes

518

of disease, in general the clinical APACHE II score and contrast-enhanced CT criteria do not yield similar results in many of these patients; the APACHE II score appears superior to CT criteria as an indicator of disease severity.

The overall mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis is almost 50%.

Focal Pancreatitis

At times acute pancreatitis involves only a portion of the pancreas, with such focal pancreatitis then evolving into chronic changes limited to a segment of the pancreas. A separate description here of focal pancreatitis is not meant to imply that it is a separate disease entity; rather, its importance lies in its mimicry of pancreatic cancer.

An annular pancreas, with pancreatitis limited to the annular portion, has already been discussed. Some descending duodenal stenoses are secondary to focal pancreatitis in the annular segment.

A history of acute or chronic pancreatitis is often lacking in those with focal pancreatitis. Most often focal pancreatitis involves the pancreatic head. Computed tomography shows focal pancreatitis to be hypodense and US reveals hypoechoic tumors. It tends to be hypervascular at angiography.

Groove Pancreatitis

One form of segmental chronic pancreatitis is called “groove pancreatitis.” The groove is located between the pancreatic head, the duodenum, and the common bile duct. Why focal pancreatitis should develop preferentially in this location is puzzling, although this region of the pancreas is drained by the duct of Santorini, and obstruction of this duct or aberrant ducts may play a role. Relation of this entity to focal annular pancreatitis is conjecture.

A typical appearance is a tumor simulating a pancreatic head carcinoma; differentiation between the two entities is difficult at best, and some of these patients undergo resection. Some develop a duodenal stricture.

Magnetic resonance imaging in five patients revealed a sheet-like tumor between the pancreatic head and duodenum (35); these tumors were hypointense relative to the pancreas on T1-

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

and isoto slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images and had delayed contrast enhancement. Histology revealed fibrosis.

Inflammatory Pseudotumor

A number of pancreatic inflammatory pseudotumors have been described. Whether these should be considered a type of focal pancreatitis or as a separate entity is not clear.

Computed tomography detects an inflammatory pseudotumor of the pancreas simply as a large tumor; histology shows a mixed infiltrate of spindle cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells.

Chronic Pancreatitis

Even repeat bouts of acute pancreatitis do not necessarily lead to chronic pancreatitis. In fact, clinical evidence suggests that chronic pancreatitis is a de novo condition and that acute and chronic pancreatitis should be considered separate diseases.

The most common cause of chronic pancreatitis in North America and Europe is alcohol related.

Classification

No universally acceptable classification of chronic pancreatitis exists. The diagnostic criteria of chronic pancreatitis using ERCP criteria were proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society in 1995 and are used by some. The Marseilles classification defines chronic pancreatitis as continued inflammation of the pancreas associated with irreversible damage. The pancreas may be involved focally or diffusely, and there is loss of both exocrine and endocrine function. Abdominal pain is a constant feature in the vast majority of patients.

Etiology

Many of the etiologies causing acute pancreatitis are also responsible for chronic pancreatitis. Nevertheless, some conditions lead primarily to chronic inflammation (Table 9.2). Aside from cystic fibrosis and hereditary pancreatitis (see Congenital Abnormalities), chronic pancreatitis is rare in children and adolescents. Some families with familial hyperlipidemia, cystic fibrosis,

519

PANCREAS

Table 9.2. Conditions associated with chronic pancreatitis

Mostly in young patients Hereditary (familial) pancreatitis a1-Antitrypsin deficiency Familial hyperlipidemia

Cystic fibrosis

Familial hyperparathyroidism Congenital syphilis

Idiopathic fibrosing pancreatitis of childhood

Chronic calcific pancreatitis

Tropical calcific pancreatitis

Pancreatitis in severe protein malnutrition

Infection

Viral

Tuberculous pancreatitis

Amebic pancreatitis

Schistosomiasis

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Idiopathic

Associated with Sjögren’s syndrome

Associated with sarcoidosis

Sequelae of pancreatic trauma

Associated with ulcerative colitis

and hyperparathyroidism have a higher than normal prevalence of chronic pancreatitis. a1- Antitrypsin deficiency is typically associated with pulmonary disease; in rare instances it may be associated with chronic pancreatitis.

Chronic pancreatitis has been associated with ulcerative colitis; the several reported patients suggest a possible nonfortuitous relationship between these two entities. The prevalence of chronic pancreatitis is low in primary sclerosing cholangitis, and the occasional synchronous finding is probably by chance. Some cirrhotic patients have ERCP findings consistent with chronic pancreatitis. These changes are found even in nonalcoholic cirrhotic patients.

Clinical

Idiopathic Fibrosing (Autoimmune)

A syndrome of idiopathic fibrosing pancreatitis, also called chronic relapsing pancreatitis of childhood, is a rare form of chronic pancreatitis, often developing in children and young adults. Etiology is unknown, although an

autoimmune basis is postulated. Its relationship to autoimmune hepatitis, a well-established entity, is not clear.

Pain is a common feature. These patients have developed obstructive jaundice, but pancreatic insufficiency is not a prominent feature in this entity.

A curious form of chronic pancreatitis is centered on the pancreatic ducts, called autoimmune pancreatitis, sclerotic pancreatitis and lymphoplasmacytic pancreatitis. Whether these represent the same entity is conjecture. Imaging reveals either a focal pancreatic tumor or the entire pancreas is enlarged and is hypoechoic with US. Pancreatography in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis reveals an irregular and narrowed main pancreatic duct; some patients develop pancreatic duct obstruction. Neither pancreatic duct dilation nor calcifications develop (36). A focal pancreatic tumor, often with pancreatic duct obstruction, is not an uncommon presentation, and surgery for suspected pancreatic cancer is performed. Retroperitoneal fibrosis develops in an occasional patient (37). Resection, often for suspected pancreatic cancer, reveals pancreatic fibrosis and, at times, an eosinophilic infiltrate. Fibrosis, of course, is not limited to this condition and is common in chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Disease often recurs in the remnant pancreas. Their pancreatitis tends to respond to steroid therapy.

An autoimmune mechanism appears to be involved in Sjögren’s syndrome, and the first sign of Sjögren’s syndrome can be evidence of chronic pancreatitis. A not untypical scenario is the patient with a narrowed distal common bile duct believed to be neoplastic in origin, but resection reveals inflammation and fibrosis.

Chronic Obstructive

Duct obstruction with little or no evidence of stones is classified an a separate etiology for chronic pancreatitis. Yet this term is also a descriptive one representing a stage in evolution of chronic pancreatitis due to a number of etiologies, including secondary to inflammation of sphincter of Oddi, acute pancreatitis, or even a malignant tumor. Some patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pancreatitis do develop ductal stones and, similarly, of those with chronic calcifying pancreatitis not all

520

have calcifications throughout their disease course.

Chronic Calcifying

Chronic calcifying pancreatitis is most often associated with chronic alcohol consumption; gallstone pancreatitis rarely progresses to calcifying pancreatitis. An exception to this is a young patient with gallstone pancreatitis and pseudocysts who eventually develops pancreatic calcification; superimposed hereditary pancreatitis may play a role in some of these patients.

The presence of pancreas divisum does not change the course of chronic calcifying pancreatitis; in these patients pancreatitis may involve only the ventral segment, only the dorsal segment, or occur throughout the pancreas; in about half of these patients detected abnormalities are segmental.

Tropical Calcific

Tropical calcific pancreatitis generally starts in childhood. The etiology is not known, although these patients tend to have underlying nutritional deficiencies.

Tuberculous

Isolated tuberculous pancreatitis or a pancreatic abscess are rare. This entity is more often seen in association with lung tuberculosis.

Peripancreatic and mesenteric lymph nodes are often also enlarged, bowel wall is thickened, and ascites is present. Some patients have hepatosplenic involvement and splenic vein thrombosis. Tuberculous pancreatitis presents as a pancreatic tumor, at times containing cystic components, and tends to mimic a primary pancreatic neoplasm, including an appearance of vascular invasion. Some patients undergo laparotomy for suspected cancer. Attempted resection risks formation of a pancreatic fistula and miliary peritoneal dissemination.

Focal tuberculomas are hypodense on CT. US shows inhomogeneous hypoechoic tumors within the pancreas.A cystic component may be evident. Endoscopic US is often compatible with a cystic pancreatic neoplasm.

Even ERCP reveals a stricture, and pancreatic duct displacement can mimic a neoplasm.

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Other Etiologies

Eosinophilic pancreatitis is a rare entity of unknown etiology. It mimics a pancreatic neoplasm. An 18-year-old man presented with obstructive jaundice, epigastric pain, and weight loss, endoscopic US detected a small round, hypoechoic tumor in the head of the pancreas, an endocrine tumor was suspected, and a duodenopancreatectomy performed (38). An ERP in another man with weight loss and obstructive jaundice identified a narrow, smooth main pancreatic duct and a tight common bile duct stenosis (38). Both patients were eventually diagnosed with eosinophilic pancreatitis.

Hydatid disease of the liver as a cause of pancreatitis has been mentioned above (see Acute Pancreatitis). Direct pancreatic involvement is rare. These cystic lesions tend to be misdiagnosed as pseudocysts and ascribed to pancreatitis or trauma. About half of the cysts occur in the head of the pancreas, a somewhat uncommon location for pseudocysts. Calcifications may develop.

Pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis develop in congenital syphilis.

In the Middle East, schistosomiasis (due to

Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium) leads not only to hepatobiliary but also to pancreatic calcifications.

A hydatid cyst in the head of the pancreas can result in obstructive jaundice.

Malignant Potential

Although pancreatic cancer is often associated with surrounding pancreatitis, the risk of carcinoma developing in a setting of chronic pancreatitis is not known. Histology in patients with advanced chronic pancreatitis revealed duct epithelial hyperplasia in 31%, focal squamous metaplasia in 21%, cellular dysplasia in 8%, and dysplastic acinar nodules in 21% (39); overall, extensive pancreatic fibrosis was associated with epithelial anomalies in 66% of patients.

Pathology

Acinar atrophy, acinar dilation, and intralobular fibrosis are typical histologic findings, although a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is not always straightforward, even for pathologists.

521

PANCREAS

Autopsies in patients with chronic alcohol abuse reveal two distinct pathologic patterns of fibrosis: either perilobular or intralobular, suggesting different etiologic factors (40). The perilobular type is irregular, occasionally patchy, and when advanced extended into intralobular regions to the point of completely replacing pancreatic tissue by fibrosis. Intralobular fibrosis, on the other hand, is uniform in distribution. Such ancillary findings as protein plugs, pancreatic duct hyperplasia and stones, extensive intraand peripancreatic fibrosis, splenic vein and bile duct involvement, and pseudocyst formation are more common with perilobular fibrosis.Associated liver cirrhosis is greater with intralobular fibrosis.

Imaging

The imaging differential of chronic pancreatitis includes changes found in the elderly; one should keep in mind that some degree of pancreatic atrophy and scaring and dilation of pancreatic ducts occur in elderly patients with no previous history of pancreatitis. Also, residual duct scarring after a bout of severe acute pancreatitis is not a sign of chronic pancreatitis.

In a setting of chronic pancreatitis the gland atrophies, pancreatic ducts dilate, and stasis of pancreatic secretions occurs, even without obstruction. The etiology for such stasis and duct dilation is incompletely understood, but includes chronic duct wall inflammation, dilation of capillaries, and loss of duct epithelium; duct obstruction results in reflux of luminal content into extracellular space. A tortuous and beaded duct appearance is common.

Endoscopic US is considerably more sensitive than abdominal US in diagnosing chronic pancreatitis. Sensitivity for ERCP is only about 75%, but specificity approaches 100%. Whether CT or MRI is more sensitive in detecting early changes of chronic pancreatitis is arguable; CT detects subtle calcifications better, but MRI is better at identifying fibrosis.

Computed Tomography

A CT finding of focal pancreatic enlargement often raises the possibility of a pancreatic malignancy. Pancreatic duct dilation is non-

specific and is found in pancreatitis or malignancy, or is a normal finding in the aged.

Ultrasonography

Sonographic pancreatic texture in chronic pancreatitis ranges from hypoechoic to hyperechoic, with the latter representing calcifications.

A controversy in endoscopic circles is whether in chronic pancreatitis endoscopic US is preferred over ERCP. Abnormal findings may be detected earlier with endoscopic US than with ERCP. In a setting of chronic pancreatitis, endoscopic US and ERCP show good correlation in measuring the size of the duct of Wirsung. Duct dimensions on ERCP tend to be larger than those obtained with other imaging modalities because of x-ray magnification and distention with contrast. Endoscopic US reveals dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, heterogeneous echogenicity of the pancreatic parenchyma, and small cysts. Endoscopic US detects pseudocysts and occasionally may suggest a superimposed pancreatic carcinoma.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Atrophy, a heterogeneous appearance, and a dilated pancreatic duct are common MR findings in chronic pancreatitis. Fibrosis tends to decrease the signal intensity on T1-weighted fat-suppression images. Decreased heterogenous arterial phase contrast enhancement is common; nevertheless, gadolinium enhanced MRI in patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma can show similar abnormal pancreatic enhancement in both entities. The two cannot be distinguished based on degree and time of enhancement (41).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography tends to overestimate pancreatic duct stenosis and underestimate the dilation of secondary branches and filling defects in the pancreatic duct (42), but it is superior to ERCP in depicting that part of the pancreas distal to an obstruction.

Pancreatography

Pancreatography findings in patients with chronic pancreatitis and an inflammatory tumor range from a smooth or irregular stenosis, to obstruction or a patent duct; the length of

522

stenosis varies. The pancreatic duct distal to the tumor is dilated in about three fourths of patients. Irregular dilation of secondary pancreatic ducts develops throughout the pancreas in some patients with diffuse mild chronic pancreatitis. When localized, similar changes are also found with neoplasms or simply reflect changes seen with age.

The secretin-pancreozymin test and ERCP concur in most patients with chronic pancreatitis. A majority of patients with an abnormal ERCP but normal secretin-pancreozymin test have a prior history of acute pancreatitis, but no clinical or laboratory evidence of chronic pancreatitis. Thus both tests complement each other when chronic pancreatitis is suspected because ERCP tends to overdiagnose this condition. Secretin-stimulated MRP in patients with chronic pancreatitis visualizes more pancreatic duct segments and secondary ducts and more stenoses and intraluminal defects than presecretin (43). At times acinar filling develops postsecretin in chronic pancreatitis. This test also aids in assessing pancreatic exocrine function. Thus reduced duodenal filling postsecretin in patients with chronic pancreatitis achieved a 72% sensitivity and 87% specificity in detecting decreased function (44).

Calcifications

The only reliable and almost pathognomonic imaging finding of chronic pancreatitis is pancreatic calcifications, readily identified by both CT and conventional radiography (Fig. 9.8). A majority of these calcifications are intraductal in location, in either the main duct or side branches. These calcifications are multiple and vary in size. They may be limited to a portion of the pancreas or be scattered throughout. With time, these calcifications remain static or increase in extent, although in an occasional patient they may decrease. The extent of calcification has a poor correlation with the degree of pancreatic exocrine dysfunction.

Occasionally similar calcifications develop in severe protein malnutrition. Pancreatic parenchymal calcifications may also develop after direct trauma to the pancreas and possibly after ischemia. Biliary and pancreatic calcifications have been reported in schistosomiasis.

It has been observed that patients with chronic pancreatitis have a higher prevalence of

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

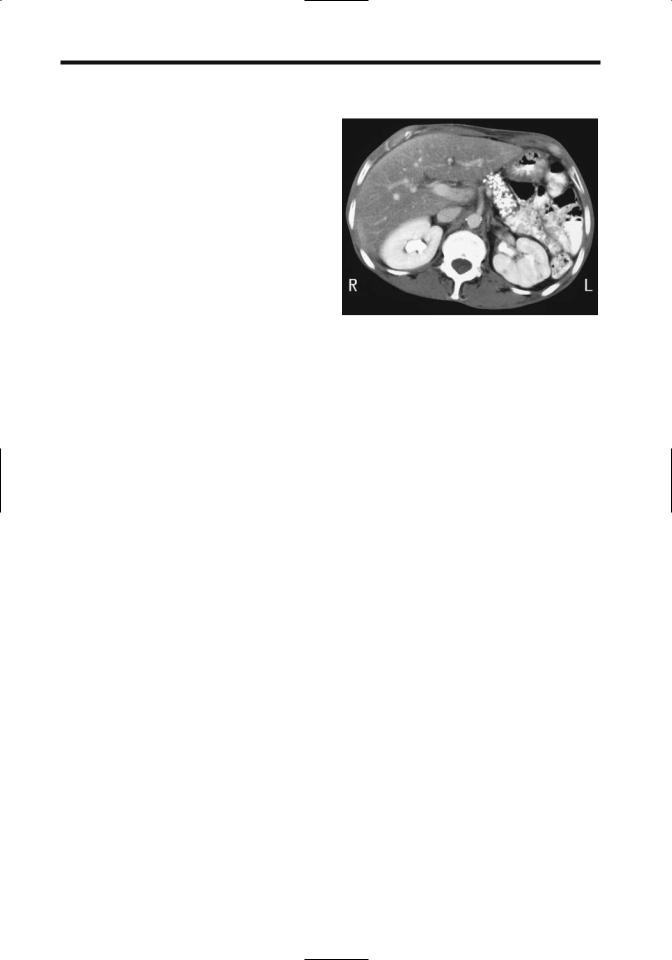

Figure 9.8. Chronic pancreatitis. Computed tomography reveals extensive calcifications that have replaced most of the pancreatic parenchyma. (Courtesy of Patrick Fultz, M.D., University of Rochester.)

aortic calcification than a control population (45).

Therapy

Most therapy in chronic pancreatitis revolves around attempts to control pain. Confounding treatment is that pain disappears spontaneously in some of these patients.

Endoscopic

One source of pain in these patients is increased pancreatic duct pressure. Endoscopic sphincterotomy or main pancreatic duct stenting reduces this pressure, and these patients have rapid pain resolution; in many of these patients such therapy is only temporary, however, and they will need to undergo more definitive procedures. A stent can be inserted in most patients even with pancreatic duct disruption. With a stricture or stone distal to the disruption and pseudocyst formation, a cystoenterostomy (either gastric or duodenal) is also necessary.

Endoscopic catheter and balloon techniques have evolved to the point that a number of main pancreatic duct concretions can be removed; currently this is not possible with calculi located in secondary branches. Therefore, if stone therapy is contemplated, it is useful

523

PANCREAS

to know a specific concretion location. This information can be provided by CT and subsequent 3D reconstruction.

Two patients with chronic pancreatitis and multiple calcifications in the main and accessory pancreatic ducts underwent intraductal infusion of citrates through a nasopancreatic catheter (46); the stones fragmented and dissolved.

Extracorporeal Shock-Wave Lithotripsy

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is viable initial therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stones in the main pancreatic duct unretrievable by ERCP. Published results are encouraging. Stones are disintegrated and complete stone clearance obtained in 75% to 80% of patients. A combined endoscopic-ESWL approach is often used. Clinical pancreatitis is rare after ESWL therapy. Not all patients are cured of their pain, and some eventually required a Whipple or Puestow procedure for relief of symptoms or persistent obstruction.

Surgical

Partial common bile duct obstruction is common in chronic pancreatitis. Without relief of obstruction, these surgical high-risk patients progress to cholangitis and cirrhosis. Biliary imaging provides a road map for surgical planning. Common surgical procedures to relieve intrapancreatic biliary obstruction are choledochoduodenostomy or choledochojejunostomy.

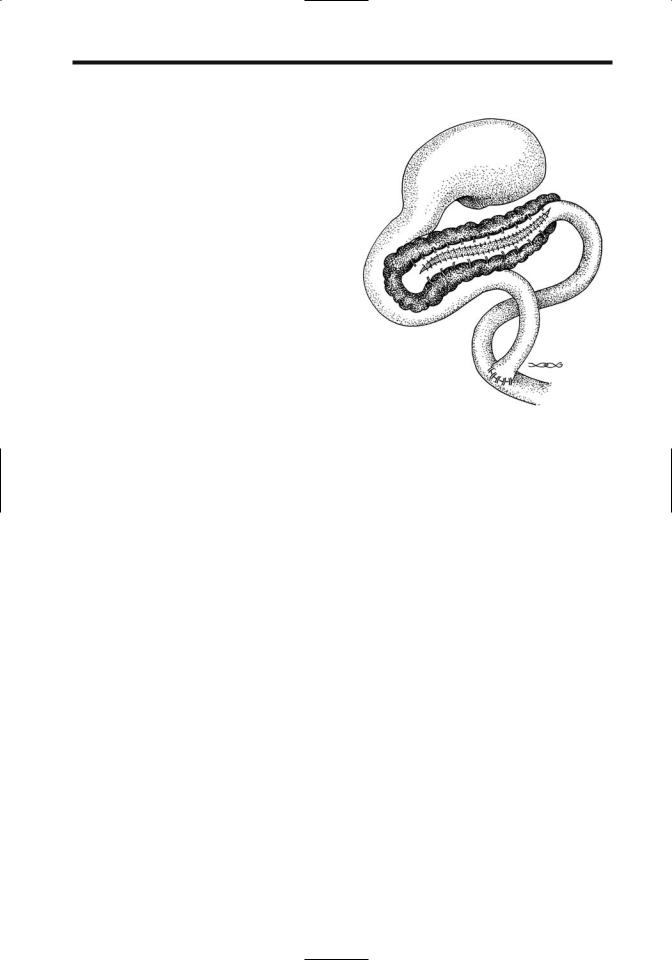

A Puestow procedure consists of a lateral side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy, useful to decompress a dilated pancreatic duct (Fig. 9.9). If no pancreatic tissue is resected, little change in existing endocrine or exocrine function should be evident. Computed tomography identifies most of these pancreaticojejunal anastomoses located anterior to the pancreatic body or tail; fluid, gas, or oral contrast is evident next to the anastomosis in some. Such fluid or gas either close to the anastomosis or in an adjacent Roux-en-Y loop should not be confused with an abscess. Complications of a Puestow procedure include fluid collections, abscess, pseudocyst, hematoma, and small-bowel or Roux-en-Y obstruction.

Partial pancreatic resection is considered for a failed pancreaticojejunostomy, localized

Figure 9.9. Appearance of a lateral side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy (Puestow procedure).

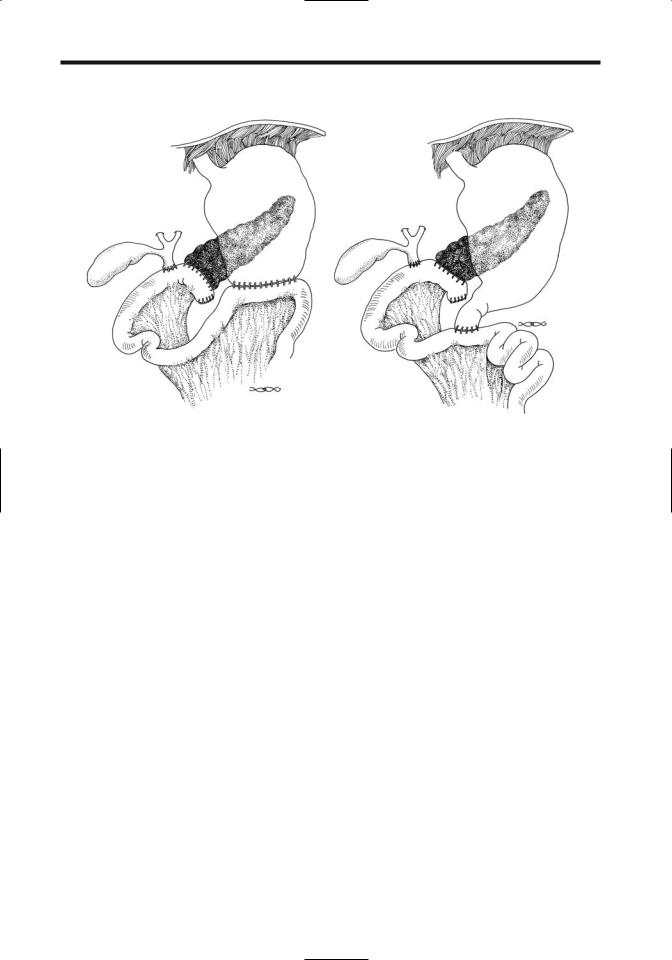

disease, or if the pancreatic duct is not dilated. With resection of pancreatic head and duodenum (Whipple procedure), a Roux-en-Y is performed and the common bile duct and residual pancreatic duct anastomosed to the jejunum. A complication after this operation is breakdown at the pancreaticojejunostomy. As a result, pancreatic duct anastomosis into the stomach has become common; an anastomotic breakdown here is less likely. A duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection together with a pancreaticogastric or pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is a viable alternative in some centers (Fig. 9.10).

A distal pancreatectomy is performed if disease is limited to the body or tail of the pancreas. Patients undergoing a distal pancreatectomy have a better outcome than those with a pancreaticoduodenectomy or pancreaticojejunostomy).

Complications of Pancreatitis

Pancreatic necrosis and infection were discussed in a previous section. The complications covered here include pancreatic and gastrointestinal fistulas, pseudocysts, and changes involving other structures.

524

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

A

B

Figure 9.10. Schematic of a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure). A: A pancreaticojejunostomy is proximal to the choledochojejunostomy and a gastrojejunostomy is more distal. B: A similar procedure to that in part A, except that a pylorus-sparing duodenojejunostomy is substituted for the gastrojejunostomy. The biliary anastomosis can be studied via a T-tube and the gastric anastomosis with oral contrast, but the pancreaticojejunostomy is not readily accessible. Indirect evidence of a breakdown of this anastomosis is provided by CT detection of an abscess in this region. In place of a pancreaticojejunostomy some surgeons perform a pancreaticogastrostomy.

Fistulas

Pancreatic duct disruption leads to an undrained collection and pseudocyst formation; in a similar setting a pancreatic fistula forms after necrosectomy and external drainage. In general, the mortality rate is higher with a gastrointestinal fistula as compared to a pancreatic fistula or pseudocyst. A persistent pancreatocutaneous fistula develops in about half of patients after percutaneous drainage of pancreatic fluid collections (47); whether a fistula develops or not appears related primarily to the severity of pancreatitis rather than to its cause. A pancreaticopleural fistula is rare.

An occasional pancreatic duct fistula is visualized by ERCP. Some of these fistulas are also identified by CT and US. Biliary scintigraphy appears worthwhile with a suspected biliary fistula developing in a setting of chronic pancreatitis.

Anecdotal reports describe fibrin glue being used to successfully occlude these fistulas.

Pseudocyst

Clinical

Pancreatic pseudocysts develop in both acute and chronic pancreatitis. It takes 4 to 6 weeks for a pseudocyst to “mature” and form into a welldefined structure with an identifiable wall. These cysts can be classified as intrapancreatic or extrapancreatic in location; the location is best defined with CT. A mature cyst may or may not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system; such communication is best established with ERCP. Noncommunicating cysts are probably secondary to necrotic liquefaction of pancreatic tissue or prior limited communication with pancreatic ducts. In chronic pancreatitis the cysts generally communicate with ducts and tend to be associated with main pancreatic duct obstruction.

Although the most common site for pseudocysts is around the tail of the pancreas,they have been reported in almost any location in the

525

PANCREAS

abdomen and occasionally even in the chest. Pseudocysts have developed in intrahepatic and intrasplenic locations. They have involved both the right and left liver lobes. A pseudocyst originating from the tail of the pancreas has extended into the left renal space and has mimicked a renal cyst on CT.

Pseudocysts vary considerably in size. Most small pseudocysts resolve spontaneously. The wall of some chronic pseudocysts calcifies. Pseudocyst content amylase and lipase levels do not correlate with exocrine pancreatic function, and cyst enzyme levels vary considerably between consecutive punctures of the same cyst; with noncommunicating cysts the pseudocyst content differs from pancreatic juice.

Diagnosis

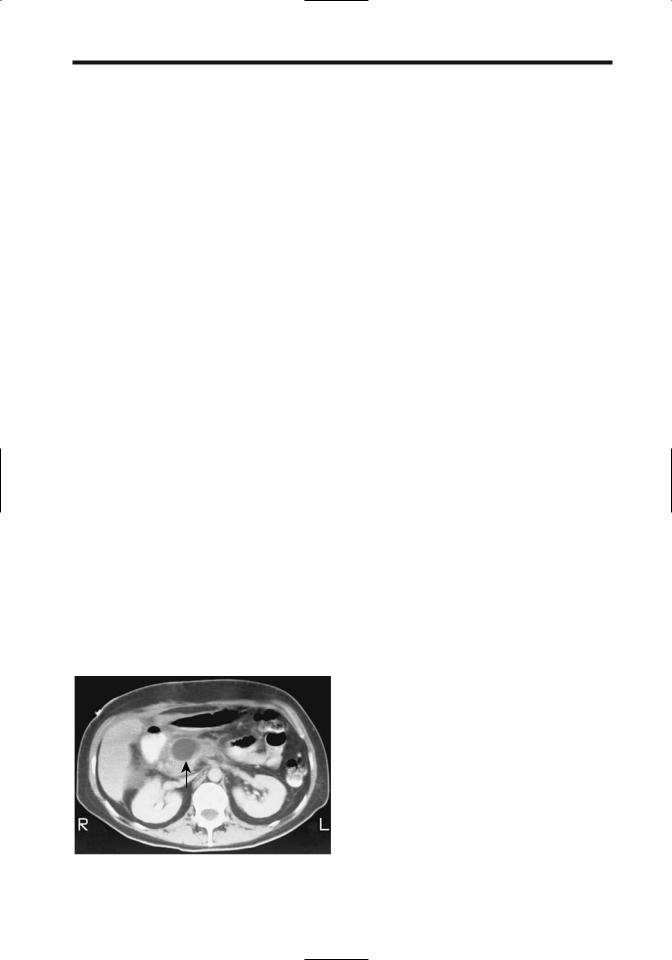

Computed tomography of an uncomplicated pseudocyst shows fluid of near-water density. Either hemorrhage or infection increases attenuation. Pseudocysts have smooth margins (Fig. 9.11).

An uncomplicated pseudocyst is anechoic, but hemorrhage, debris, or infection produces a heterogeneous complex echo pattern. Blood clots appear as a solid component.

An MRCP readily detects these cystic structures. Communication with pancreatic ducts is not as readily apparent as with ERCP.

It is worthwhile to emphasize that not all pancreatic cysts are pseudocysts. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms and true cysts are also in the differential diagnosis. About three quarters or more

Figure 9.11. Pseudocyst in pancreatic head, an unusual location (arrow). (Courtesy of Patrick Fulz, M.D., University of Rochester.)

of all pancreatic cysts are pseudocysts secondary to pancreatitis, with the others being primarily neoplastic. Complicating the issue is that some pancreatic neoplasms are associated with pancreatitis. It is essential to differentiate among a pseudocyst, a neoplastic cyst, and other nonneoplastic cysts. A number of reports describe what initially appears to be a pseudocyst, which is treated by a cystenterostomy, with subsequent dire consequences. Even a gastric duplication has been misdiagnosed as a pancreatic pseudocyst. A cystic neoplasm should be considered especially in patients without a history or risk factors for pancreatitis.

A reverse misdiagnosis can also occur. Thus imaging in a 37-year-old asymptomatic man being investigated for hypertension detected two small cysts and a larger unilocular cyst containing a mural nodule in the pancreas; ERCP showed communication of the pancreatic duct with a cyst but no ductal changes, suggesting chronic pancreatitis was evident and a tentative diagnosis of a malignant mucinous cystic neoplasms was made (48). Intraoperative frozen section of the cyst wall revealed a pseudocyst, with mural nodules representing sludge within the pseudocyst.

A cystic pancreatic neoplasm and a pseudocyst have a similar US appearance. Serial US, especially if obtained early in the formation of a pseudocyst, aids in differentiating between these two. When small, an aneurysm is also in the US differential diagnosis; Doppler US should differentiate these.

The relative MR signal intensity on T1weighted images of pseudocysts, other benign cysts, and cystic neoplasms overlaps. Other rare cystic nonneoplastic pancreatic lesions include retention cysts and simple cysts.

Pseudocyst Complications

A pseudocyst can rupture into any adjacent structure. Spontaneous rupture into surrounding structures results in surrounding inflammation and possible sinus tracts between the pseudocyst and duodenum. Perforation can occurred into the colon. A pseudocyst can erode into the portal vein, with embolization of pseudocyst content into the intrahepatic portal vein branches. Rupture into the peritoneal cavity results in acute peritonitis. Differentiation from infected pancreatic ascites is difficult.

526

Prevalence of pseudoaneurysms in pancreatitis patients is difficult to gauge but probably is around 10%. Many of the smaller ones remain silent unless rupture occurs or they are discovered with an imaging study. Spontaneous arterial hemorrhage associated with a pseudocyst is not uncommon. The involved vessel becomes dilated (pseudoaneurysm formation) and ruptures. Bleeding is into the pseudocyst, intraperitoneal, into the gastrointestinal tract, through the papilla of Vater (hemosuccus pancreaticus), or into any structure surrounding the cyst. Bleeding is generally from one of the peripancreatic arteries (49), although any nearby artery, including the splenic artery and even the middle colic artery, can be involved. Bleeding ranges from slow to massive to the point of exsanguination.

Contrast-enhanced CT should detect high attenuation blood within a pseudoaneurysm. During an acute bleed CT may detect extravasating contrast.

Ultrasonography identifies an aneurysm as a cyst, often with an adjacent crescent rim. Doppler US should detect blood flow and allows differentiation of a pseudoaneurysm from a pseudocyst or other fluid collection.

Angiography allows transcatheter embolization of the feeding vessel. Although embolization arrests most acute bleeding, it may recur and require reembolization. Steel coil embolization is more successful than Gelfoam embolization. Unsuccessful bleeding artery embolization usually necessitates a pancreatectomy (49).

Infection turns a pseudocyst into an abscess. Differentiation of a noninfected from an infected pseudocyst is an art and relies on clinical and imaging findings. Positive Tc-99m- HMPAO leukocyte scintigraphy suggests a pancreatic abscess; on the other hand, a normal scintigram points toward a noninfected pseudocyst.

A pseudocyst may obstruct any adjacent hollow viscus. Thus with bile duct compression patients develop obstructive jaundice. A rare large pseudocyst results in gastric or small bowel obstruction.

Pseudocyst Therapy

Pseudocysts are treated by a number of percutaneous (repeat cyst aspiration, external catheter drainage, transgastric catheter

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

drainage), endoscopic (transgastric catheter, transampillary stenting, insertion of nasocystic drainage catheter), and surgical procedures. Internal drainage to the stomach or bowel has varying degrees of success. The type and degree of aggressive intervention varies depending on the expertise of the physicians involved and the traditions of the institution. Overall, a trend has been away from open surgical drainage to nonsurgical intervention. Simple aspiration has a high recurrence rate and is not often performed. Percutaneous catheter drainage has a recurrence rate similar to surgical internal drainage, but is associated with fewer complications. A percutaneous transgastric approach, with resultant internal drainage into the stomach, is used in a number of institutions with good results and a low recurrence rate. A percutaneous catheter allows serial study of cyst size and any pancreatic duct communication. A double-mushroom stent has been described to provide internal drainage into the stomach (percutaneous cystogastrostomy), thus avoiding an external catheter. Recurrence of a pseudocyst should suggest a persistent or recurrent pancreatic duct obstruction by a stone.

Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts is performed in some centers. Endoscopic US prior to the procedure detects any interposed larger vessels (including varices) and aids in establishing the best site for drainage. A pancreaticoportal fistula is a complication after an endoscopic cystogastrostomy (50).

In general, a high-resolution imaging study aimed at detecting any associated pseudoaneurysm is performed prior to pseudocyst drainage. If a pseudoaneurysm is detected, angiography allows confirmation and embolization.

Intrasplenic pseudocysts have been drained percutaneously. A percutaneous paraspinal, extrapleural CT-guided approach was used to drain a mediastinal pseudocyst (51).

Abscess

Some pancreatic phlegmons evolve into an abscess. A pseudocyst can become infected. The infecting agent usually is bacterial, with only an occasional one being fungal. Klebsiella sp.,

Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus predominate, and most infections contain only one organism.