Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

507

PANCREAS

cinoma originated in ectopic pancreatic tissue in the esophagus, and a papillary cystic neoplasm developed in ectopic pancreatic tissue in the omentum.

Aberrant Duct Insertion

During embryonic development a network of duct branches eventually fuses and forms a primary channel. Aberrant fusion leads to a number of duplication anomalies of the pancreatic ducts and results in one or more main duct. This congenital anomaly is often associated with an apparent tumor on CT imaging.

The pancreatic duct can communicate with a duodenal duplication or even involve aberrant bile ducts and the patient presents with a periampullary cystic tumor; CT and ERCP are helpful in defining the underlying anatomy and planning surgery.

Cysts

Congenital cysts of the pancreas are either true cysts or pseudocysts. Both are rare. They range from solitary to multiple. True cysts are lined by epithelium. These cysts in neonates tend to be large and their clinical differential diagnosis often includes renal, choledochal, mesenteric, ovarian, and gastrointestinal origin cysts.

An increased prevalence of simple cysts is found in patients with polycystic kidney disease, tuberous sclerosis, and von HippelLindau disease. Incidentally detected multiple pancreatic cysts, especially in a young patient without pancreatic disease, should suggest one of these entities. Patients with von HippelLindau disease are also prone to developing cystic pancreatic neoplasms. In fact, in an occasional patient pancreatic lesions are the only abdominal manifestation of von Hippel-Lindau disease.

Computed tomography or MR confirms a cyst’s location and its relationship to pancreatic parenchyma; imaging tends not to differentiate among congenital cysts, a cystic neoplasm, and other cystic lesion.

Precontrast CT of a lymphoepithelial cyst revealed a heterogeneous water-density tumor, with septa identified postcontrast (9); MRI showed a hypointense mass on T1and a hyper-

intense mass on T2-weighted imaging, with septa identified on postgadolinium images. Endoscopic US confirmed the presence of septa and also detected fine hyperechoic structures within the cyst. A cystic neoplasm was suspected preoperatively.

Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the current term for disorders previously known as histiocytosis X. This is a rare disorder, with pancreatic involvement being even rarer.

Hereditary Pancreatic Dysfunction

Pancreatic dysfunction due to an isolated embryogenetic defect is rare. More often dysfunction is part of an inherited abnormality manifesting at multiple sites. Cystic fibrosis is an example of the latter. It is the most common cause of hereditary pancreatic dysfunction.

Cystic Fibrosis

In this autosomal-recessive disorder obstruction of small and large pancreatic ducts by thick, viscid secretions and surrounding inflammation induces fibrosis and an eventual atrophic pancreas. As a result, most patients develop exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Acute pancreatitis is not common in cystic fibrosis patients, with some authors postulating that their pancreatic atrophy prevents a major inflammatory response.

Pathologically, parenchymal atrophy, fibrosis, and fatty infiltration are evident. In some patients fatty infiltration predominates and the pancreas appears enlarged; in others, atrophy predominates with varying degrees of fatty infiltration.

Calcifications are not common in chronic pancreatitis secondary to cystic fibrosis. When present, calcifications are scattered and not as prominent as in hereditary pancreatitis. Cysts, fatty replacement, and atrophy are detected with imaging. Once small, the pancreas may have a CT density approaching that of fat, similar to severe lipomatosis. Cysts are interspersed with segments of dilated pancreatic ducts or

508

they may essentially replace the pancreatic parenchyma.

Computed tomography in adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis revealed less pancreatic tissue and more fat than in controls (10); no relationship was found between the degree of pancreatic fat and pancreatic endocrine dysfunction, but a relationship existed between the degree of fatty replacement and exocrine dysfunction.

The varied composition is reflected in the US appearance, which can range from normal to a hyperechoic pattern caused by fibrosis and fatty infiltration. In some, the pancreas blends into surrounding extraperitoneal fat and is difficult to define. Likewise, smaller cysts are not identified.

Magnetic resonance signal intensity varies depending on the degree of fatty infiltration and fibrosis present. Pancreatic T1-weighted MR in patients with cystic fibrosis reveals hyperintense signals ranging from homogeneous to a lobular outline,focal sparing,and even a normal appearance. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is useful in evaluating pancreatic duct dilation and cyst formation.

Hereditary Pancreatitis

The rare hereditary (familial) pancreatitis eventually leads to pancreatic exocrine dysfunction. It has an autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance with variable penetrance, but tends to affect only a few members of each family. This genetic defect is believed to be due to mutations in the trypsinogen gene leading to failure in inactivating prematurely activated cationic trypsin within acinar cells (11); two types are described: type I involves mutations in trypsinogen R117H and type II in trypsinogen N211. Accumulation of active trypsin mutants are believed to activate a digestive enzyme cascade process in pancreatic acinar cells, leading to autodigestion, inflammation, and acute pancreatitis. An enzymatic mutation detection method is accurate in screening individuals for known trypsinogen gene mutations.

Two types of pancreatic stones develop in this condition. Calculi in members of 10 families were composed of degraded residues of lithostathine, a pancreatic secretory protein inhibiting calcium salt crystallization (12); in

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

one family with five affected individuals calculi were composed of >95% calcium salts.

This condition typically develops in childhood or early adolescence as acute episodes of pancreatitis, evolves into chronic pancreatitis, and gradually progresses with episodes of pancreatitis, including pseudocyst formation, to pancreatic insufficiency. An early diagnosis prior to onset of chronic pancreatitis is often not considered. Compared to patients with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, patients with chronic hereditary pancreatitis have an earlier onset of symptoms, a delay in diagnosis, and a higher prevalence of pseudocysts, but otherwise the natural history is similar for both conditions. These patients are at increased risk for developing a pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma, the risk being approximately 50 to 60 times greater than expected (13); smoking increases this risk and lowers the age of onset by approximately 20 years.

Prominent calcifications in the pancreatic ducts are a common feature and appear similar to those seen with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, except that this finding is almost pathognomonic of chronic hereditary pancreatitis in a young patient. A dilated pancreatic duct is also often detected.

Hereditary pancreatitis has a different clinical presentation and imaging findings, and usually is not in the differential diagnosis with cystic fibrosis.

Less Common Syndromes

The syndromes listed below are rare and have little radiologic relevance, but are occasionally raised in a differential diagnosis.

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome is a rare congenital disorder consisting of pancreatic insufficiency, growth retardation, and other abnormalities. These patients have steatorrhea, a normal sweat test, and normal intestinal mucosa. Some eventually improve their enzyme secretions and have pancreatic sufficiency. Imaging shows extensive replacement of pancreatic tissue by fat.

Pearson marrow-pancreas syndrome manifests during early infancy with failure to thrive and involves the hematopoietic system, exocrine pancreas dysfunction, and others. A primary defect involves deletions in mitochondrial DNA.

509

PANCREAS

Johanson-Blizzard syndrome is an autoso- mal-recessive syndrome consisting of ectodermal dysplasia. Among other abnormalities, these infants develop both exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency. The primary defect is in acinar cells; at autopsy some of these infants have total absence of acini and the pancreas is replace by fat.

Histopathologically, patients with the Johanson-Blizzard syndrome and SchwachmanDiamond syndrome have preserved ductular output of fluid and electrolytes; this distinguishes them from patients with cystic fibrosis, who have a primary ductular defect.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia

Syndromes

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes are familial autosomal-dominant disorders exhibiting incomplete penetrance and variable expression and manifesting by an increased incidence of various endocrine hyperplasias or neoplasms. They consist of synchronous or metachronous neoplastic and hyperplastic neuroendocrine tumors in several glands. These syndromes are usually divided into three types:

Type I (Wermer’s syndrome) consists of lesions in the pancreas, parathyroid, adrenal cortex, pituitary, and thyroid. Some gastric carcinoids also share a common development with enteropancreatic and parathyroid MEN-I tumors.

Type II (Sipple’s syndrome) consists of lesions in the adrenal medulla, parathyroid, and thyroid.

Type III (multiple mucosal neuroma syndrome) consists of lesions in the adrenal medulla, thyroid, mucosal tissues, and bones.

Whether von Hippel-Lindau disease and neurofibromatosis are part of multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes is a matter of classification.

The presence of pancreatic tumors in a patient with MEN syndrome signifies type I. The genetic defect for MEN-I appears to involve a tumor suppressor gene located in the long arm of chromosome 11. A majority of MEN-I individuals occur in familial clusters, with only an

occasional sporadic one reported. Affected patients tend to have multiple organs involved, multicentric tumors within one organ are common, and complex hormone secretions are encountered. MEN-I tumors have a low but not insignificant malignant potential. Pancreatic tumors tend to be multicentric and most are hormone secreting, some being multihormonal; in fact, in the same patient different tumors often have different predominant hormonal secretions. Most common tumors are a-cell (glucagon) and b-cell (insulin) secretors. Less common are PP-cell, gastrin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide tumors. Concomitant nesidioblastosis occurs in a minority of patients. These tumors range from hyperplasia, adenoma to a carcinoma.

The majority of MEN-I patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome also have primary hyperparathyroidism, 30% have pituitary adenomas (about half are prolactinomas), 30% have adrenal tumors, and a smaller minority have bronchial and thymic carcinoids (14); gastrinomas tend to be multiple and often are duodenal in location. Hypercalcemia and nephrocalcinosis are common initial clinical presentations.

Because of multiplicity of tumors and their malignant potential, management of MEN-I patients with symptomatic pancreaticoduodenal tumors remains controversial. One aggressive surgical approach in a setting of hypergastrinemia and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome includes a duodenotomy, peripancreatic lymph node dissection, enucleation of pancreatic head or uncinate tumors, and a distal pancreatectomy (15); such an approach in MEN-I patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome resulted in 68% of patients remaining eugastrinemic during follow-up. The effect on survival of a Whipple resection is not clear.

Gastrinomas in MEN-I syndrome patients tend to be duodenal in location and difficult to locate with imaging. Some are detected only during surgical exploration by palpation, intraoperative endoscopy with transillumination, or duodenotomy.

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type II is an autosomal-dominant condition with the gene abnormality located on chromosome 10, with the responsible gene, called RET, being an oncogene. These patients are at sufficiently high risk for medullary thyroid carcinoma at a young age

510

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

that a thyroidectomy is considered once a diagnosis is confirmed.

One patient with MEN-II also had Hirschsprung’s disease (16); aganglionosis involved the distal 5cm of the rectum. Whether this association is fortuitous is not clear.

von Hippel-Lindau Disease

A relationship probably exists between pancreatic microcystic adenomas and von HippelLindau disease; VHL gene alterations are detected in these tumors both in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease and in those with sporadic microcystic adenomas. These patients are at increased risk for pancreatic and adrenal neuroendocrine tumors.A not uncommon presentation is with large liver metastases.

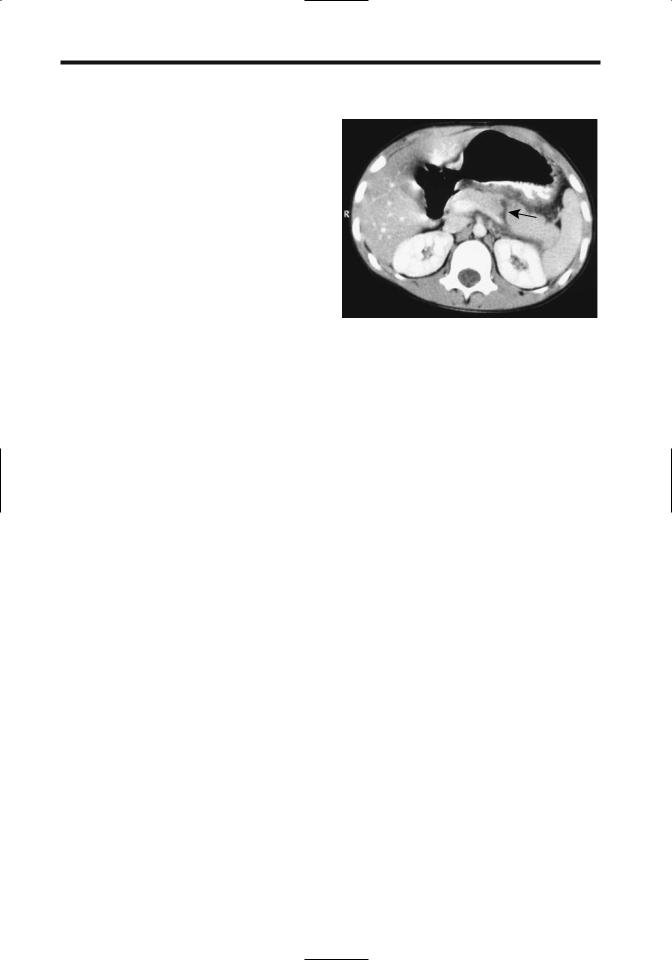

Figure 9.5. Traumatic pancreatic rupture (arrow) in a 7–year- old boy. (Courtesy of Algidas Basevicius, M.D., Kaunas Medical University, Kaunas, Lithuania.)

Trauma

A note on definition: surgeons define distal pancreas as that part containing the tail of the pancreas, while proximal means pancreatic head.

A pancreatic injury classification scale, devised by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, is outlined in Table 9.1. Other abdominal injuries are common in patients with pancreatic trauma. The exception is with bicycle handlebar injuries, which are a common cause of mechanical pancreatic trauma in children; these tend to produce iso-

Table 9.1. Surgical pancreatic injury scale

Grade* |

Type of injury |

|

|

|

|

I |

Hematoma |

Minor contusion |

|

Laceration |

Superficial laceration; no duct injury |

II |

Hematoma |

Major contusion |

|

Laceration |

Major laceration; no duct injury or |

|

|

tissue loss |

III |

Laceration |

Distal transection or parenchymal |

|

|

injury with duct injury |

IV |

Laceration |

Proximal transection or |

|

|

parenchymal injury involving |

|

|

ampulla |

V |

Laceration |

Massive pancreatic head disruption |

|

|

|

* Advanced one grade for multiple injuries, up to grade III. Source: Modified from Moore et al. (17).

lated pancreatic injury and often lead to pseudocysts.

Both clinical and radiologic diagnosis of pancreatic injury is fraught with difficulty. Even in a setting of major pancreatic injury, at times initial physical findings are mild or masked by other trauma. Both CT and ERCP are often necessary to diagnose pancreatic fracture and duct disruption (Fig. 9.5). The most common site for fracture is at the pancreatic head and neck junction.

In many institutions CT is the imaging modality of choice in suspected pancreatic trauma. In both adults and children CT findings of pancreatic trauma can be subtle. At times an adjacent hematoma is the only suggestion of pancreatic injury. A pancreatic laceration, including complete transection, may not be apparent initially with CT. Therefore, with a strong suspicion for pancreatic injury and an unremarkable initial CT, a follow-up study 12 to 24 hours later is often helpful.

A CT finding of fluid (peripancreatic blood) separating the splenic artery or vein from pancreas suggests pancreatic injury. Still, such fluid may also be present in the absence of any pancreatic injury, and thus additional CT findings should be sought.

In general, CT cannot directly detect pancreatic duct injury, although a deep pancreatic laceration suggests duct disruption. Endoscopic

511

PANCREAS

retrograde cholangiopancreatography is the primary study in evaluating pancreatic duct injury. Nevertheless, to better delineate pancreatic duct injury, one group of Japanese investigators performed repeat CT shortly after completing ERCP, believing that such an approach confirms ERCP findings, detects injuries not identified on ERCP, and excludes injuries in patients with equivocal ERCP (18).

Magnetic resonance pancreatography can detect complete main pancreatic duct disruption, although the literature on this topic is sparse. Current MRCP application is primarily in defining pancreatic ducts not evaluated with ERCP.

Management of children admitted with a diagnosis of pancreatic injury is individualized, keeping in mind that, in the absence of clinical deterioration or major duct injury, a more conservative therapeutic approach has evolved than practiced previously. In children with pancreatic injury a primary consideration of whether to operate or not often depends on the status of the pancreatic duct. Yet even with duct injury the trend is toward more conservative therapy. Anecdotal reports suggest that some transected pancreatic ducts recanalize spontaneously.

Duct disruption in some patients, at times involving a secondary or smaller duct, leads to pseudocyst formation. Classic therapy for traumatic pancreatic pseudocysts is cystogastrostomy or distal pancreatectomy. Children with pancreatic duct disruption and pseudocysts, however, have had successful long-term cyst catheter drainage (19).

Infection/Inflammation

Acute Pancreatitis

Classification

Acute pancreatic inflammation does not lend itself to an easy classification. Since 1963, at least four international symposia have debated this subject and proposed classifications. Among the changes adopted has been a shift in emphasis from pancreatic necrosis to presence of organ failure and inclusion of information obtained from various imaging examinations (inciden-

tally, the terms pancreatic necrosis and necrotizing pancreatitis are used synonymously). Some of the terminology has also been redefined. There now is a distinction between an acute fluid collection that occurs early in acute pancreatitis and often regresses spontaneously and a pseudocyst that requires several weeks to form and has a distinct wall. A pancreatic abscess is defined as an intraabdominal collection of pus near the pancreas that contains little if any necrotic tissue. The term infected pseudocyst has been deleted and this entity is now considered a pancreatic abscess.

The terms hemorrhagic pancreatitis and phlegmon have also been deleted, although the wisdom in deleting the term phlegmon has been questioned. The primary reason for deleting phlegmon was its past imprecise usage. For instance, some physicians interpret phlegmon to mean a sterile process while others place it in the infectious category. Nevertheless, the vagueness of this term is useful during initial evaluation of acute pancreatitis prior to imaging studies; contrast-enhanced CT can then subdivide a phlegmon into interstitial versus necrotizing pancreatitis, while percutaneous aspiration can establish a sterile versus infected collection of fluid. It remains to be seen whether phlegmon will continue to be used in a setting of acute pancreatitis.

Etiology

Congenital Anomaly

Aberrant pancreaticobiliary duct insertions are associated with recurrent pancreatitis. Thus a pancreatic duct inserting into a communicating duodenal duplication or diverticulum and cystic duct insertion close to the ampulla have resulted in pancreatitis. Even a communicating duplication results in stasis, and, in time, calculi form within a duplication. The rare intraluminal duodenal diverticulum is also associated with acute pancreatitis.

Some patients with pancreas divisum develop pancreatitis; therapeutic options in this clinical setting are discussed in the Congenital Abnormalities section.

In the absence of more common etiologies for pancreatitis, especially in a younger patient, aberrant pancreaticobiliary duct communica-

512

tions and termination should be sought. An MRCP should detect any major duct anomalies and related fluid-filled structures suggesting a duplication. The inability to cannulate the main papilla during ERCP should prompt efforts to cannulate the duct of Santorini.

Bile Duct Related

Acute biliary pancreatitis appears to be more severe; more complications develop and mortality is greater in patients who have an intact gallbladder compared to those who had a previous cholecystectomy.

Choledocholithiasis is a common cause of acute pancreatitis. Although not common, gallstone pancreatitis does occur during pregnancy. Presumably a stone impacts at the ampulla of Vater, but most of these obstructions are transient and the stone passes into the duodenum. About 40% of gallstone pancreatitis recurs within 6 months, with recurrence often associated with stones in the gallbladder, and thus the rationale for performing cholecystectomy once pancreatitis is quiescent.

Clinically it is difficult to differentiate between gallstoneand non–gallstone- associated acute pancreatitis. One useful laboratory test is alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level; a greater than threefold elevation above normal has a strong positive predictive value for acute gallstone pancreatitis.

Admission plasma cholecystokinin levels in patients with gallstone pancreatitis are significantly higher than in patients with other causes of acute pancreatitis (20), although cholecystokinin levels do not correlate with serum bilirubin or pancreatic enzyme levels or severity of acute pancreatitis. Plasma cholecystokinin elevation in gallstone pancreatitis appears to be a result of a transient bile flow disturbance by stones or duct wall edema.

Hemobilia, regardless of cause, is associated with acute pancreatitis.

Anecdotal etiologies of acute pancreatitis include a bile duct suture or clip acting as a nidus, debris from a hepatocellular carcinoma rupturing into the bile ducts, and associations with primary sclerosing cholangitis and duodenal Crohn’s disease. A patient with familial adenomatous polyposis with adenomas in the common bile duct developed relapsing acute pancreatitis (21).

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Ethanol

Ethanol ingestion is the most common cause of acute pancreatitis in the United States.

Endoscopic Retrograde

Cholangiopancreatography Induced

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is a not uncommon cause of subclinical or mild pancreatitis. Of more importance is that ERCP is an occasional precursor to acute necrotizing pancreatitis, especially if a sphincterotomy is performed. Among 72 consecutive patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis requiring surgery at the Mayo Clinic, ERCP was implicated in 8% (22); of note is that on admission these post-ERCP patients had higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) scores, more extensive pancreatic necrosis, and a higher rate of infected necrosis, and they required earlier necrosectomy and developed more enteric fistulas than similar non–ERCP-induced acute necrotizing pancreatitis patients. These post-ERCP patients had a lower mortality rate, but they were significantly younger; nevertheless, all survivors suffered long-term morbidity. The authors postulated that infection introduced during ERCP may account for some of the increased severity of pancreatitis in these patients.

A relationship appears to exist between common bile duct diameter and the subsequent risk of sphincterotomy-induced pancreatitis, with pancreatitis developing more often in patients with a nondilated bile duct.

Infection

Infectious organisms linked to pancreatitis include viral (mumps, measles, Coxsackie, hepatitis B, cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus), bacterial (mycoplasma, legionella, leptospira, salmonella), fungal (aspergillosis), and occasional parasitic infestations (toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis, ascariasis) (23). Even a scorpion bite has been implicated. Acute fatal necrotizing pancreatitis has developed after liver transplantation for fulminant hepatitis B virus infection, presumably due to the hepatitis B virus.

An ascaris roundworm migrating into the pancreatic duct after sphincterotomy and pan-

513

PANCREAS

creatic stent placement led to acute pancreatitis (24). These worms can be removed with a Dormia basket.

Intrabiliary rupture of a hydatid cyst and the subsequent spill of cyst contents into the bile ducts is a cause of acute pancreatitis; CT and US identify both the liver infection and bile duct debris.

Neoplasm

Pancreatic carcinomas are commonly associated with surrounding pancreatitis, although symptoms related to the cancer tend to predominate.

An occasional papilla of Vater carcinoid or a pancreatic islet cell tumor produces a pancreatic duct stricture and a clinical picture consistent with acute pancreatitis.

Drug Related

Steroids, diuretics, some antibiotics, and even cimetidine are some of the medications implicated in acute pancreatitis. Yet drug-associated pancreatitis is uncommon. Organophosphate insecticide toxicity is a rare cause of pancreatitis. Intranasal snorted heroin is associated with pancreatitis (25).

Vascular

Pancreatic ischemia is not common but does result in pancreatitis. Thus patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair and descending thoracic aorta cross-clamping are subject to pancreatic ischemia and pancreatitis.

Cholesterol crystal embolization to the pancreas has led to necrotizing pancreatitis. Such embolization probably is more common than reported in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Other Etiologies

Rarer conditions associated with pancreatitis include the vasculitides, hyperlipidemia, ulcerative colitis, chronic renal failure, a peri-Vaterian diverticulum or neoplasm, and even a choledochal cyst. Acute pancreatitis in long-distance runners is more common in women. A rare cause of acute pancreatitis is pancreatic volvulus associated with a hiatal hernia (26).A patient

with duodenal obstruction distal to the papilla occasionally presents with acute pancreatitis; more distal small bowel obstruction is not associated with pancreatitis. Thus an obstructing duodenal carcinoma distal to the papilla of Vater or even an afferent loop obstruction after a gastrectomy and Billroth II gastrojejunostomy has led to acute pancreatitis. Hypercalcemia due to hyperparathyroidism is a known cause of acute pancreatitis. Hypercalcemia secondary to a malignancy, on the other hand, seldom causes acute pancreatitis.

Clinical

Acute injury to the exocrine pancreas and resultant inflammation is the hallmark of acute pancreatitis. Usually the entire pancreas is involved. The pancreas becomes edematous and inflamed, with these changes then spreading to surrounding structures. Pancreatic enzyme release leads to tissue necrosis and hemorrhage. Pancreatic ascites is uncommon in necrotizing pancreatitis.

Typical clinical findings of acute pancreatitis are well known, but unusual presentations abound. At times acute pancreatitis initially is painless, with the patient presenting in shock or coma. Pancreatitis can mask an underlying pancreatic carcinoma. A patient with acute pancreatitis presented with symptoms referable to the scrotum (27); surgical exploration revealed fat necrosis of tunica vaginalis and spermatic cord.

A biliary etiology is most common in patients over the age of 65 years developing acute pancreatitis, and it is more likely to be necrotizing. Age in itself is not a risk factor for complications, but a relationship exists between coexistent diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and renal failure and subsequent complications. Overall mortality is greater in the elderly.

Encephalopathy due to liver disease is well known. Less commonly encountered is encephalopathy associated with acute pancreatitis.

Traditional laboratory tests of acute pancreatitis consist of serum amylase and lipase levels. These enzyme levels do not correlate with disease severity and in some patients with acute pancreatitis are normal; a better test appears to be serum phospholipase A2 activity, which correlates with the severity of acute pancreatitis and remains high during the severe episode

514

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Figure 9.6. Jaundice due to pancreatitis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Postoperative ERCP was unsuccessful. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography reveals marked duct dilatation to the level of the superior pancreatic margin. Only a thin channel is evident in the intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct (arrow). (Courtesy of David Waldman, M.D., University of Rochester.)

(28). In patients with acute pancreatitis, endotoxin in blood and peritoneal fluid is related to subsequent morbidity and mortality, suggesting that the presence of endotoxin identifies patients at high risk early in the course of acute pancreatitis (29). C-reactive protein level is a relatively accurate predictor of pancreatic necrosis.

Clinically, differential diagnoses for acute pancreatitis include bowel ischemia, perforated ulcer, and other intraabdominal catastrophes. Acute pancreatitis can be a difficult diagnosis, especially in a postoperative patient who becomes jaundiced, and more common etiologies for jaundice are generally considered (Fig. 9.6).

Imaging

Serial imaging is useful not only to follow disease progression, but also to detect complications. Once a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is established, among other questions, imaging should address the following:

2.Is the disease evolving into pancreatic necrosis?

3.Is infection superimposed on pancreatic necrosis?

4.Are other sequelae developing, such as a pseudocyst?

The answers to these questions influence not only further diagnostic testing but also the choice of therapeutic modalities to be employed.

Although pancreatic necrosis can be suspected clinically, it is better identified by imaging and, at times, at surgery. Superimposed infection of necrotic tissue can also be suspected clinically, but the diagnosis is confirmed by imaging-guided percutaneous aspiration and bacteriologic sampling.

Imaging studies tend to be normal in mild pancreatitis. Generally the first abnormal finding is diffuse pancreatic enlargement. When focal, the pancreatic head is most often involved. The pancreatic outline becomes irregular. Further progression leads to necrosis, hemorrhage, and peripancreatic fluid.

Gas within the pancreas is not common in pancreatitis. Rarely, gas is seen in both pancreatic parenchyma and ducts. In general, intrapancreatic gas suggests an underlying abscess. Nevertheless, pancreatic and peripancreatic gas is found in other conditions, such as after recent laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Pleural effusion is not an early sign of pancreatitis; generally clinical or other CT findings of severe pancreatitis occur first. The presence of a pleural effusion on admission is indicative of severe disease and has a negative prognostic value. Likewise, pancreatic necrosis is more common in patients with pulmonary infiltrates, and these patients also have a higher mortality rate.

Acute exacerbation in a setting of chronic pancreatitis may have few imaging findings. At times the presence of peripancreatic inflammation is the only finding in a patient with clinically severe acute exacerbation, although superimposed changes of chronic pancreatitis are often found.

Computed Tomography

1.Is the etiology due to gallstone disease or aberrant ducts?

Does administration of IV contrast media, such as during CT, worsen the outcome in acute pan-

515

PANCREAS

creatitis? Using comparable clinical scores at initial diagnosis, studies tend to show that clinical pancreatitis lasts longer in patients who receive contrast as part of a CT study than those who do not, yet most of these studies are retrospective and thus have an inherent bias.

In general, CT provides better detection of peripancreatic inflammation, hemorrhage, and abscesses than US. Dynamic CT aids in defining the extent of necrosis.

The earliest CT finding is diffuse pancreatic enlargement; less often detected is focal enlargement. Computed tomography findings do not always correlate with clinical impression, and even with acute edematous pancreatitis CT can be normal. Also, imaging findings tend to lag behind clinical resolution, especially with phlegmonous pancreatitis when imaging findings can persist for months.

Inflammation evolves into an inflammatory mass, or phlegmon, which upon further damage results in pancreatic necrosis (Fig. 9.7). A

phlegmon usually has a higher CT attenuation than water and is heterogeneous in appearance due to contained blood and debris. Most phlegmons exhibit poor contrast enhancement. Nonenhancing pancreatic tissue on CT is assumed to represent pancreatic necrosis (i.e., dead tissue). Nevertheless, not all nonenhancing tissue represents necrosis. At times follow-up CT reveals enhancement, indicative of viable tissue, in a region that previously did not enhance.

Surrounding tissue inflammation is common and is identified as a hazy peripancreatic thickening of fascial planes. Peripancreatic fat increases in attenuation, and these tissues reveal increased contrast enhancement. Extrapancreatic fluid collections develop with progression in severity, with fluid dissecting along tissue planes to the transverse colon, mesentery, or even spleen and left kidney. Often this fluid is not well defined, has low attenuation, tends to be poorly marginated, and consists of

A

Figure 9.7. Examples of necrotizing pancreatitis. A: CT reveals mild contrast enhancement in the pancreatic head and essentially no enhancement in the body and tail. Fluid surrounds these structures. Pancreatitis resolved only after 8 months. B: CT reveals little enhancement in the pancreatic head and body but mild enhancement in the tail, reflecting extensive necrosis. The portal vein is thrombosed. A nephrogram is evident in the kidneys but no contrast excretion was identified. Vicarious contrast excretion has occurred in the gallbladder. (Courtesy of Patrick Fultz, M.D., University of Rochester.) C: The pancreas in another patient is replaced by a large soft tissue tumor containing gas (arrows). Ascites is also present. (Courtesy of Algidas Basevicius, M.D., Kaunas Medical University, Kaunas, Lithuania.)

B

C

516

extravasated pancreatic secretions, fat necrosis, edema, and hemorrhage. Colonic wall thickening, often first detected by CT, implies an advanced severity and increased risk for a complicated clinical course (30).

In patients with obliterated perivascular fat planes, a ratio of superior mesenteric artery diameter to superior mesenteric vein diameter is useful in differentiating pancreatitis from pancreatic carcinoma (31); a ratio greater than 1.0 suggests a malignancy.

At times pancreatitis extends to the anterior abdominal wall (Cullen’s sign) or flank (Grey Turner’s sign). Computed tomography findings show that anterior periumbilical extension is not directly related to extensive extraperitoneal inflammation, nor is it related to pseudocyst formation.

Ultrasonography

The role of conventional US in acute pancreatitis is limited. In most patients US can differentiate mild or edematous acute pancreatitis from severe or necrotizing pancreatitis. One established role of US is to detect whether gallstones are present.

In uncomplicated acute pancreatitis endoscopic US often (but not always) shows an enlarged pancreas; the pancreas has either normal echogenicity or is diffusely hypoechoic. Necrotizing pancreatitis presents as a focal hypoechoic tumor with or without interspersed echogenic regions. Endoscopic US can usually differentiate between edematous and necrotizing pancreatitis and will detect peripancreatic fluid, although in some patients it is difficult to detect progression to necrosis using only US criteria.

If needed, US provides guidance for percutaneous interventional procedures.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Whether conventional MRI offers any advantage over CT in a setting of acute pancreatitis is debatable. Viable pancreatic tissue can usually be distinguishing from necrosis with either modality. Gas and calcifications are better seen with CT.

In uncomplicated pancreatitis MRI shows a normal or diffusely enlarged pancreas. With more severe involvement the pancreas becomes

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

hypointense on fat-suppressed T1-weighted images and is hypointense to normal liver. Decreased enhancement is evident on immediate postgadolinium images. Similar to CT, nonenhancing pancreatic tissue is assumed to represent pancreatic necrosis.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is useful for the initial assessment of acute pancreatitis and offers a viable alternative to diagnostic ERCP in these sick patients; therapeutic ERCP can then be performed in those with a correctable abnormality detected by MRCP.

An MRCP is especially valuable in children with acute pancreatitis. Necrosis, pseudocysts, common bile duct dilation, and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ducts can be detected.

Scintigraphy

Leukocyte infiltration of the pancreas is detected by technetium-99m (Tc-99m)– hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (hexametazime) (HMPAO) leukocyte scintigraphy. In early acute pancreatitis, positive leukocyte scintigraphy suggests a severe course, but the test is also occasionally positive in mild acute pancreatitis. Later in the course of acute pancreatitis, positive Tc-99m-HMPAO leukocyte scintigraphy suggests a superimposed infection, but here also a positive test is not synonymous with infection and is also found with milder inflammation.

Therapy

In Japan, infusion of protease inhibitors is one therapeutic modality used in acute pancreatitis (32); it is not often employed in Europe or North America.

Gallstone Pancreatitis

The evidence suggests that morbidity and mortality are decreased in patients with gallstone pancreatitis if ERCP with stone extraction is performed early in the course. An ERCP not only confirms the diagnosis, but also sphincterotomy and, if possible, extraction of any incriminating stones can be performed. This is a controversial topic; acute pancreatitis can be exacerbated by ERCP. Injection of contrast into the pancreatic duct in experimental animals